Having fun on a crowded commute is tricky – unless you can play a game. Game designer Holly Gramazio explores travel pastimes old and new, from cow-spotting to the absorbing and soothing little world of smartphone games.

How to play on the District line between Stepney Green and Embankment

Words by Holly Gramaziophotography by Thomas S G Farnettiaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Serial

For the last seven years, my default journey into London has taken me from Stepney Green to Embankment, a 16-minute ride on the District Line. It’s a nice route. Stepney Green station is decaying and almost elegant, full of pale green columns and wide platforms. You don’t get to sit down, at least not during peak hours, but maybe you get one of those spaces where you can jam yourself in near the door and lean on the glass next to the seats.

On the train you’re surrounded by people staring at the windows; people listening to music on terrible sound-leaking headphones; people with newspapers or paper books or Kindles; and by people playing games.

Games that help pass the time on a journey have a long history. Take Travelling Piquet, adapted here from the 1812 edition of Francis Grose’s ‘Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue’:

Travelling Piquet

A mode of amusing yourself for two people riding in a carriage, each counting towards their score the persons or animals that pass by on the side next [to] them, according to the following estimation:

A parson riding a grey horse: game

A cat looking out of a window: 60 points

A man, woman and child, in a buggy: 40

A man with a woman behind him: 30

A flock of sheep: 20

A flock of geese: 10

A horseman: 2

A man or woman walking: 1

Other games like this might have you looking out for pub signs, colours or advertisements; or racing through the alphabet on number plates. My personal favourite dates back to at least the 1970s:

My Cows

While you’re travelling, look out for cows.

If you’re the first person to see a particular group of cows, point at them and say, “My cows!” You may then add one cow point to your score. (Each gathering of cows counts as one cow point for the purpose of the game, regardless of whether there are three cows together, just one, or 100.)

Simple enough, right? Spot cows, get points. But there’s one complication: if at any time you pass a graveyard, you may point at one other player of your choice, and say, “All your cows are dead!” Their cow counter resets to zero.

The player with the most cows at the end of the journey is the winner.

As the game proceeds, why not add some new rules? There are plenty of variations. Some players say that cows in pictures count, and can’t be killed by a passing graveyard. Others say that if you pass a church and point at it and yell, “Marry my cows!”, you double your cows – though this rule doesn’t work well in the UK, where churches and graveyards so often coexist.

Travel games like My Cows help to pass the time, and they get players noticing the world around them while allowing for different engagement levels. They can also get surprisingly competitive. I once played My Cows with members of a company I’d been freelancing for, on a slow train journey from Bristol to London; I won, and was never invited to work for the company again.

Of course, these aren’t the games that people play on the District line between Stepney Green and Embankment. It’s not just that the cow population tends to be low underground. It’s that these games are about engaging with the outside world, looking through windows and discovering the unexpected. They are travel games, not commute games.

A commuter is on a regular journey (the word ‘commute’ comes from the US term for a season ticket. A ‘commutation ticket’ replaced a daily payment with a single price for multiple journeys). A commuter is usually ‘alone’, in the sense of not having friends or family with them, but at the same time they’re surrounded by strangers. Some games recognise this – for example:

Casting Carriage

While on a train, look around your carriage. Imagine that the people you can see are the only people left in the world. Decide which fellow passenger would be your partner, which would lead the whole group, which would become your best friend and which your personal nemesis.

This barely-a-game only needs one player, and it’s easy for that player to expand on it to fill a slightly longer journey: who will seem like an ally but will ultimately turn traitor? Who will lead a rebellion against the leader? But it’s not going to keep anyone occupied every morning and evening for weeks and months and years.

On a commute, you’re crowded in with the thumping inner lives of a hundred strangers, collectively ignoring the long minutes when the train stops in a tunnel, feeling each other’s sneezes, smelling each other’s shower-free hurried mornings, feeling the rising heat as the journey rolls on. You are dominos and one stumble or one prolonged moment of eye contact could be enough to make the whole situation entirely untenable; any disruption might break the sense that actually, this is fine.

The best games for commuters, then, are not directed into the outer world but inwards, towards the phone and the interior life of the player. They aren’t about making you pay more attention to the space you’re in, or the world outside, or even the varied and immense humanity of everyone around you. They’re about obscuring the repetition and the crowds just enough for the journey to feel OK. In 2019, this almost exclusively means games played on smartphones.

Designing the perfect commuter game

Margaret Robertson is Director of Game Development at the New York company Dots. The company’s games are perfect for a commute, engaging and meticulous and designed with the sort of clean geometry that you find if you search IKEA’s website for rugs and then sort by ‘most expensive’. Players draw long lines with their fingers to dispatch dots of matching colours; more tumble in from the top of the screen.

Robertson says that the development team refer to worry beads and other physical objects in their design, conscious of the swooping strokes of players’ fingers and how that affects the play experience. This ritual of repeating gameplay is couched within a wider narrative in which the player is on a journey. “I think the mechanical familiarity requires the sense of progression,” Robertson says. “It's what allows it to be soothing rather than repetitive or claustrophobic. I think of it in the same way I think of a train journey – it's relaxing because you're going somewhere, even though you're just sitting still.”

The best games for commuters are about obscuring the repetition and the crowds just enough for the journey to feel OK.

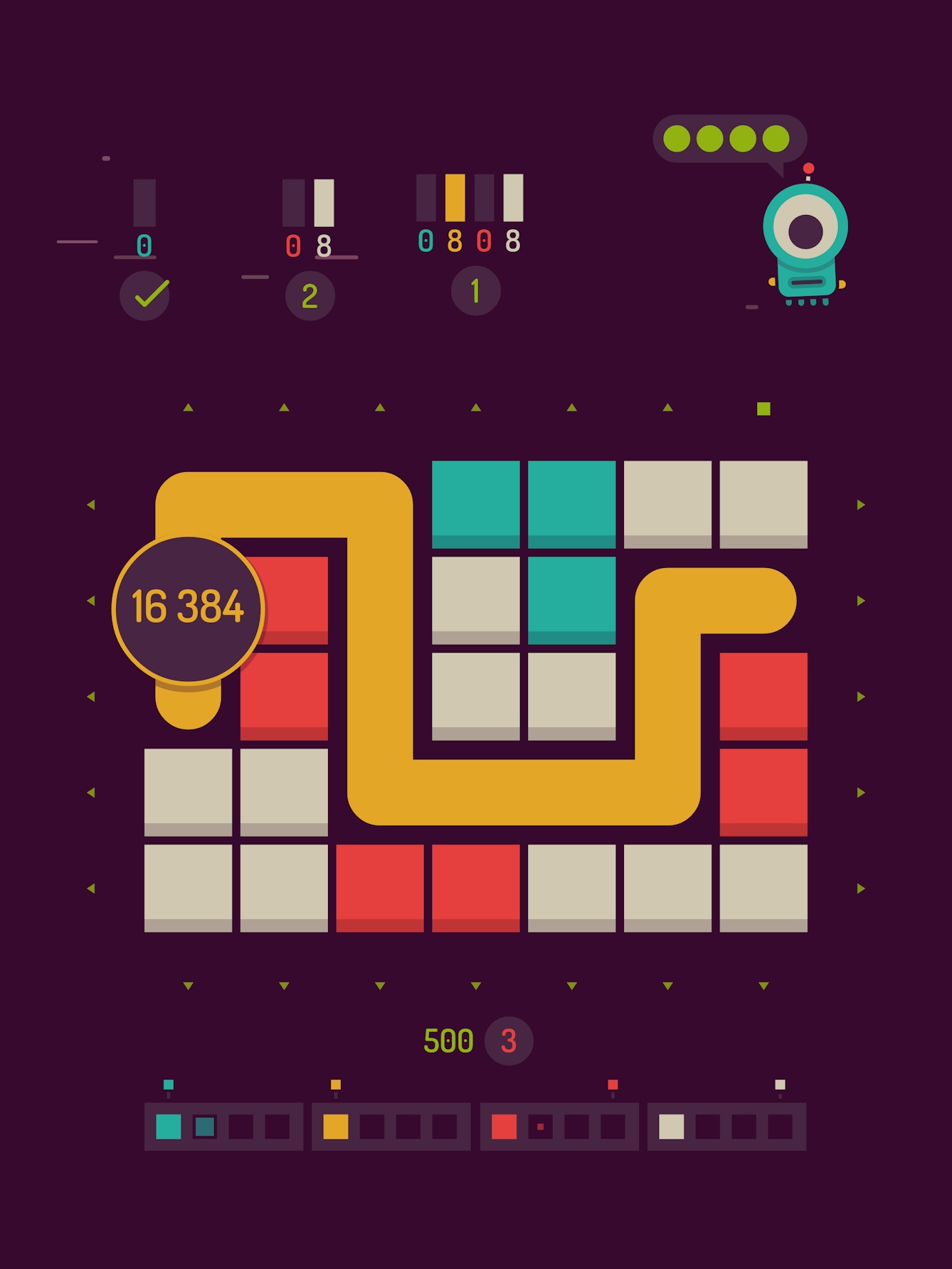

For another perspective on commuter games, I talked to Martin Jonasson of Grapefrukt Games, whose Twofold Inc. (a make-the-numbers-bigger grid game) and Holedown (Breakout, but you’re mining downwards) are such upsettingly perfect commute games that I’ve installed and deleted them over and over again as I veer between wanting a game to pass the time, and then not wanting quite so much time to pass.

Make the numbers bigger in Twofold Inc.

When I talked to Jonasson, he and I came up with a list of requirements for a perfect commuter game. There are purely practical considerations: it can’t require sound or an internet connection; it should be playable with one hand; it should work in portrait mode; if you stop playing suddenly, you should lose little or no progress.

The mental and emotional considerations are a bit more complex. If you stop and then start playing again, Jonasson says, all the information you need to resume should be right there on the screen – you shouldn’t have to build up a detailed model of the game in your head. And you should feel like you’ve done something, advanced in the game in some way, in just a couple of minutes.

A little time out from life

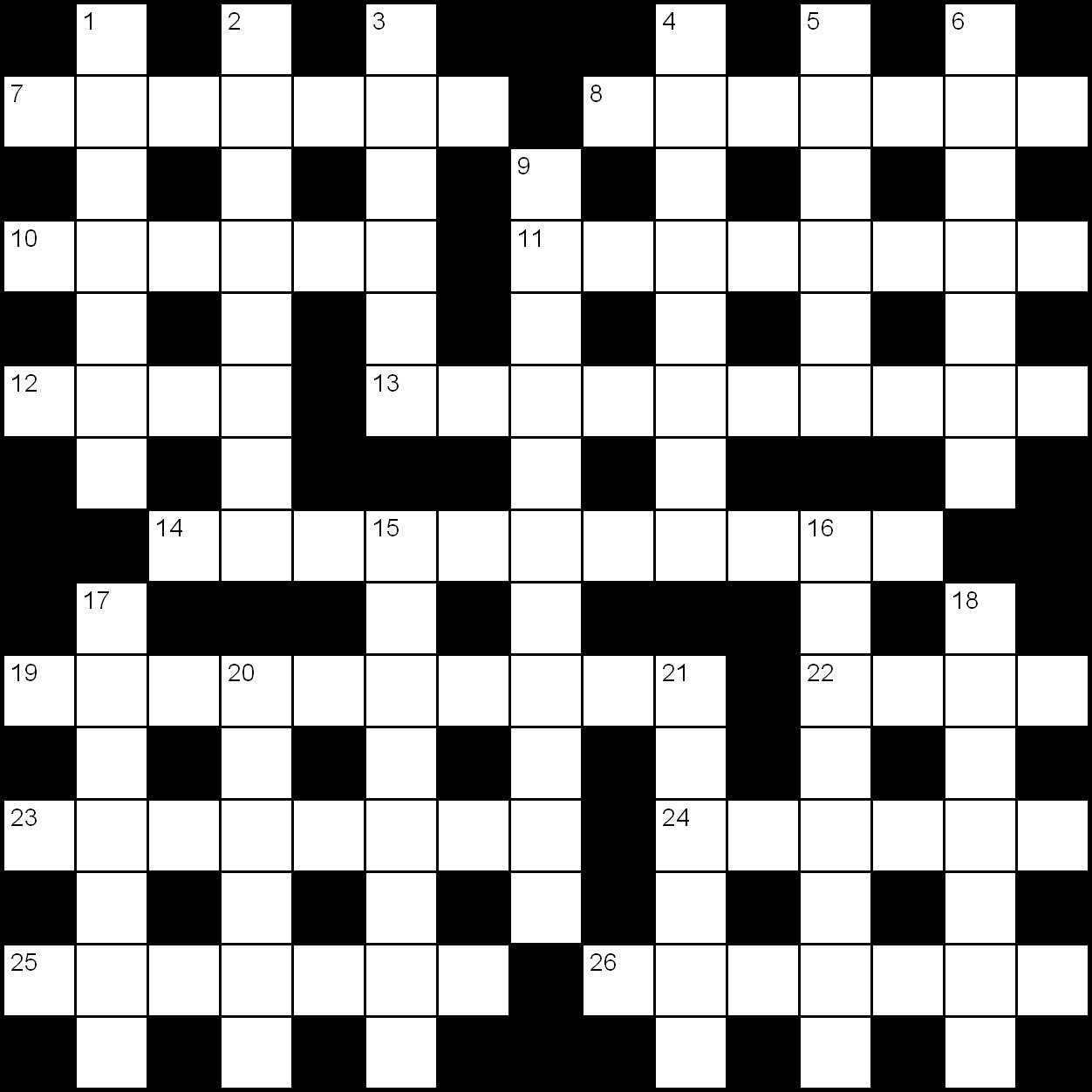

The earliest notable game that fulfils these criteria, whose grid still echoes today in games like Dots, is the crossword: perhaps the first real commuter game. The Tamworth Herald of 1924 warned that:

"Everywhere, at any hour of the day, people can be seen quite shamelessly poring over the checker-board diagrams, cudgelling their brains for a four-letter word meaning ‘molten rock’ or a six-letter word meaning ‘idler’, or what not: in trains and trams, or omnibuses, in subways, in private offices and counting-rooms, in factories and homes…"

Almost a hundred years later, the principles are the same. Small actions, a focus for attention that helps to block out the wider world, and a sense of progress as the grid fills in or you move through the game levels.

Moving through the grid.

As wifi becomes more common underground, and dead spots without phone signal become rarer above, it’s possible that we’ll see a decline in commuter games, with more and more players turning instead to the internet. Even now, between Stepney Green and Embankment, regular commuters like me know the few places where the train is close enough to the surface for a few moments of internet access. But for now, at least, we have games. As Jonasson says:

“I really do enjoy making this little world for you to live in. I’ve heard from people who say they play Holedown to escape from their own head, or wherever they happen to be. They need a time out from life for a bit. And that’s what playing the game does for them.”

About the contributors

Holly Gramazio

Holly is a game designer, curator and writer based in London. She works both independently and as half of Matheson Marcault. Her recent projects include the collaborative drawing game Art Deck and the script for the video game Dicey Dungeons. She founded Now Play This, a festival of experimental game design based at Somerset House in London, and is interested in games that get people creating or looking at their environments in new ways.

Thomas S G Farnetti

Thomas is a London-based photographer working for Wellcome. He thrives when collaborating on projects and visual stories. He hails from Italy via the North East of England.