When he started spending more time in the gym, poet Andrew McMillan observed the men pumping iron around him, whose drive to bulk up seemed more about aesthetics than health. But their desire for acceptance mirrored his own, which had formerly taken the shape of an eating disorder.

The gym of cartoon men

Words by Andrew McMillanphotography by Benjamin Gilbertaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Article

In the changing rooms of gyms and some pharmacies, there is a machine that can give you an electronic printout of the make-up of your body, like a till receipt for everything you’ve been putting into your stomach and your bloodstream over the past week. You grip the handles, stand still, stare straight ahead, and it tells you your weight, your BMI, your body fat.

My mum, in order to monitor my progress, would take me to Boots every week and make me get on one of those machines. Each week she’d collect the little roll of paper, like a child catching printed tokens as they curl out from a game in an arcade, and keep them in her purse; report cards for how I was trying to get better.

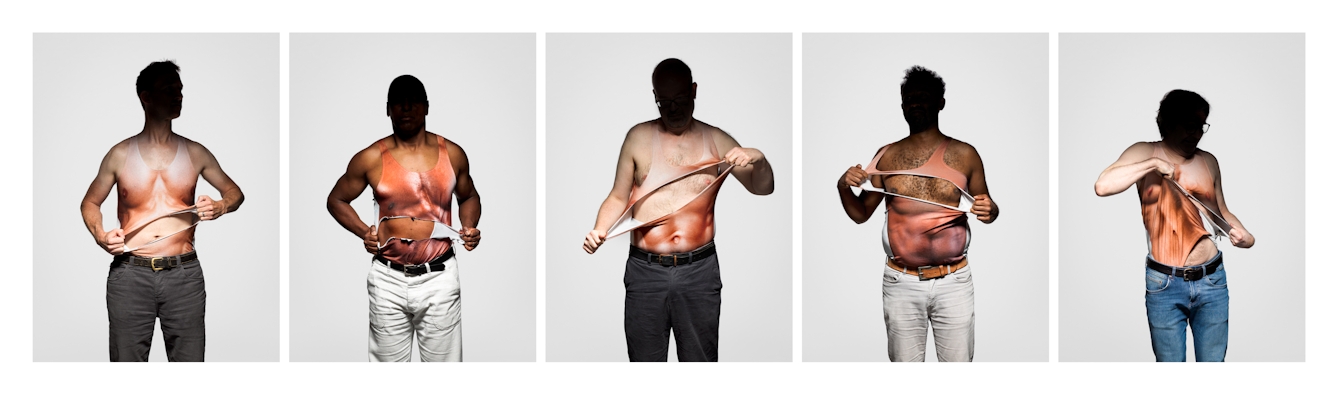

Let me go back a bit. When I was 16, the doctor banned me from going to the gym, and told me I was malnourished. I’d been starving myself, convinced this was how I would get more muscles: an idea that somehow the ideal masculine body was inside me, I just somehow had to excavate my way towards it. I’d been doing 1,000 crunches a night in front of the television, telling myself if I stopped too soon that something bad would happen to my family. I was not well.

Let me go back further. A body was never something I’d ever been conscious of having. I existed intellectually: in my studies, in books, in theatre. I was aware that my body – overweight – drew negative attention from my peers, but I had the defences of the mind. My body took up space, as men are told their bodies should, but not in the right way.

More: Writer Rupert Thomson chronicles his body’s rebellion during a period of isolation.

As I became a teenager, and naturally became more self-conscious, I started worrying more about my appearance, but never enough to do anything about it. Then, around the age of 14, I got the flu and lost a few pounds, and when I returned to school people complimented me.

Something flipped in my mind. I could no longer exist purely intellectually, because those compliments fractured something in my brain; losing weight gave me something I’d never had from other kids in school: compliments, a little admiration. Losing weight became intrinsically linked to something positive, and then that spiralled.

The never-ending quest for perfection

If I was pressed to come up with a definition of modern masculinity, I think I would say: “Never enough.” It’s no secret that men now have to live with the same tyrannical pressures on their bodies that women have had to endure for millennia. There is now such a thing as a ‘T-shirt muscle’ workout, namely one that can produce some pump in certain parts of the upper body that a T-shirt might draw attention to, but isn’t necessarily concerned with health or strength.

Indeed, the whole idea of lifting for aesthetic rather than medical benefit now seems endemic in gym spaces. ‘Ego lifters’ is the term my trainer uses; concern only for how things appear, not how they are. Like the anorexic looking in the mirror, aesthetics trumps any other concern, and it’s never enough.

There’s a really interesting correlation, actually more apparent in women than men, between eating disorders and bodybuilding. In recovery from their eating disorder, the person becomes a gym-obsessive. This might involve consuming many times more calories than they had before. But it’s something about control. About trying to give a structure to something that always feels unruly.

The prevalence of idealised male body images – in magazines, on TV, in films – gives us a lens through which we see the world and ourselves. The lens is there when you’ve been on stage giving a reading, or you’re signing books after an event, and someone wants a selfie, or a photographer is lurking, thinking they’re capturing spontaneous shots, when really they capture your face and your hands mid-contortion, as though you’ve just emerged from a wind tunnel.

Rather than starve myself, I took control a different way: I hired a personal trainer.

You’re shocked when the face they publish online isn’t the one you imagined you’d see. It’s not the idealised one on the shelves: there’s a double chin, the cheeks have lost their lift and have fallen down, like soft coastal erosion, into the sides of the neck. There is a feeling of control being lost.

When I turned 30, I’d been out and about for a few months with my book and I kept seeing these pictures of myself. I’d immediately go back to those feelings I had as an uncomfortable teenager. The road I’d gone down then wasn’t an option any more: you can’t think yourself into that state of mind. It’s like a wound that opens, and eventually closes (hopefully), though you still have the scars, which twinge or pulse every so often.

So, rather than starve myself, I took control a different way: I hired a personal trainer, someone who could set up rules and regulations to help me train my body, give me permission to enter the hyper-masculine spaces of the gym. Like arriving at a club with a minor celebrity, it’s OK, they’ll let you in; you’re with someone they trust.

When I look at the men in the free-weights area, enjoying the permission I have to be there, I imagine they look like a child’s drawing of a man. Cartoon versions of masculinity. They’re me when I was 15, trying to get to that idealised self, only they’re growing outwards, not shrinking in on themselves.

A new view of masculinity

When I first came out as gay, I went on a date with a boy I met on Faceparty, a pre-Tinder social and dating site. He lived in Darlington, me in Barnsley, so we met up in York. I remember very little, apart from walking and walking the walls of the city, as though circling our own shame and anxiety.

At some point he was talking about his ex, and he made a disparaging comment about the fact that his stomach wasn’t entirely flat. That’s all the encouragement I needed to try and fit myself into this new world I’d found myself in. I started to see my body through a new lens: not only was there an ideal male body, there was an ideal gay male body as well. When young queer kids come out, they want so much to fit in to their new community, having spent so long emotionally and physically on the outside of things.

These men in the gym are trying to do the same thing – trying to fit in. They’re waiting for another man to look at them, not with a challenge, not with disgust or anger, but simply with admiration. That’s something I think we have in common. The way forward is to treat both – anorexia in men and an unhealthy desire to bulk to unrealistic extremes – as serious health concerns that need to be tackled with new strategies.

That’s only half the battle, though; we also need to treat both types of body dysmorphia with equal seriousness, and to give men kinder and more contemporary possibilities of what masculinity could look like. Of how we might be men.

About the contributors

Andrew McMillan

Andrew McMillan was born in South Yorkshire in 1988. His two collections of poetry are the multi-award winning ‘physical’ and, most recently, ‘playtime’, both published by Jonathan Cape. He is a senior lecturer in creative writing in the Writing School at Manchester Met and is the guest editor of the ‘Explaining Men’ story series.

Benjamin Gilbert

Ben is a senior photographer for Wellcome. He is happiest when telling stories with his photographs, whether that be the health implications of rural-to-urban migration in India, or the dedication of the workers who power the NHS.