London’s Grenfell Tower is an appallingly tragic symbol of all that can go wrong with the high-rise dream. But we may have reached a turning point, where new thinking could make our postwar estates safe and healthy again.

The tower in fiction, film and life

Words by Emily Sargentaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

In June 2017, a fire tore through Grenfell Tower in North Kensington at a shocking and deadly pace, ultimately claiming the lives of 72 people. As many as 11,000 people are likely to be left suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and mental ill health in the wake of the tragedy, while the long-term health effects of toxicity caused by the fire remains uncertain.

A year on from the fire, I’m guided around the area by Constantine Gras, an artist who knows the Lancaster West Estate – and the community – very well. The sun is warm and the sound of birdsong accompanies us on our walk, as Constantine tells me the wider history of this part of London. Sharing the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea with the extraordinary wealth of South Kensington, the area known as Notting Dale in the north of the borough has long been a site of social deprivation and radical change.

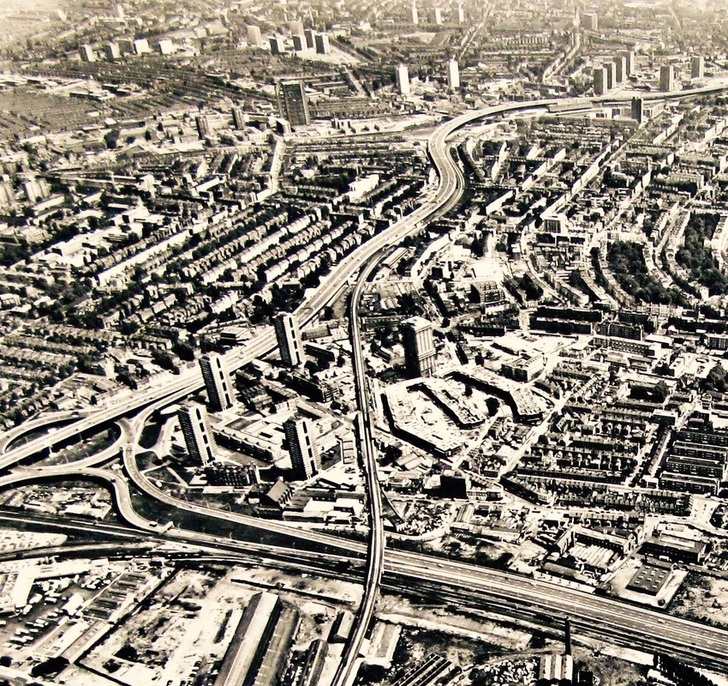

Original plans for the Lancaster West Estate included a business and shopping centre on its upper walkways, with escalators to a decking level over the railway line that separates Lancaster West from the neighbouring Silchester Estate.

It was occupied by piggeries in the early 19th century, plagued by cholera in the 1840s, and new houses were built in the 1860s. These were demolished in the 1960s to make way for new council housing, including Grenfell Tower and the Lancaster West Estate on which it stands.

Ambition and idealism

The story of Lancaster West, and the surrounding towers of the neighbouring Silchester Estate, mirrors that of many estates across the UK. An ambitious vision compromised by changes in social and political priorities; a lack of investment over time, followed by a refurbishment that was at best thoughtless, and likely to be found negligent.

One resident, Melvyn Akins, sums it up when he says Grenfell Tower now acts as “a representation of the mistreatment of people in social housing” up and down the country.

More: How the city lives inside me

A utopian dream born out of postwar planning and visions of modernity, the high-rise block has become a symbol of the failure of architecture to address social need.

Many towers were built quickly and cheaply, meaning design faults were often replicated, making the towers vulnerable to structural decay. Like the Victorian slums before them, a lack of maintenance led to problems – with broken lifts, neglected corridors and vandalism replacing the sanitary defects of old.

But the original intention of the high-rise buildings of the mid-20th century was to provide decent, healthy homes with modern kitchens and bathrooms. The idea was to increase housing density while preserving immediate access to green space.

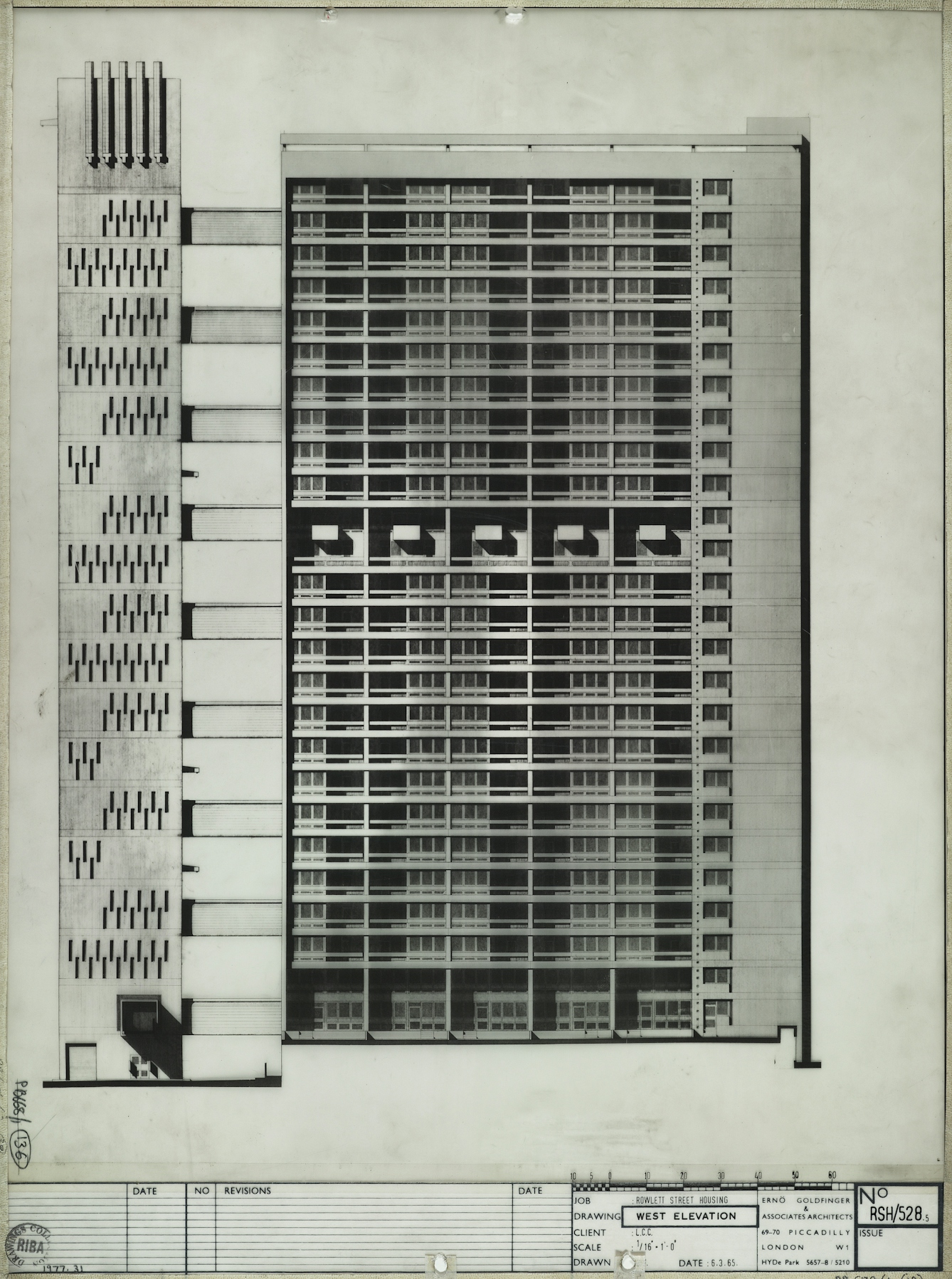

Ernő Goldfinger, a Hungarian architect who moved to the UK in the 1930s, became a key figure in the Modernist architectural movement. He designed several large developments for the Greater London Council, which included tower blocks, as well as lower and mid-rise buildings.

Ernő Goldfinger’s 1965 design for Balfron Tower in Poplar, east London.

His distinctive designs for Balfron Tower in Poplar and Trellick Tower in North Kensington are well-known landmarks in London’s skyline – and increasingly used as shorthand for both a sophisticated understanding of design and dystopian urban squalor.

The flats were carefully designed, with the services (lifts, rubbish chutes and laundry facilities) housed in a separate tower linked to the residential block. Goldfinger stated that the flats “try to solve… problems of economics, population density, the problems of children, teenagers and old people, and the problem of cars – the segregation of pedestrian from traffic”.

A utopian dream born out of postwar planning and visions of modernity, the high-rise block has become a symbol of the failure of architecture to address social need.

In the notes from his meetings with residents of Rowlett Street Housing, of which Balfron Tower formed part, Goldfinger is protective of his intention to bring the countryside into the city, saying: “The ground must be left open and free for trees, grass and for children to play. It must not be encumbered with buildings.”

The archive of the Royal Institute of British Architects holds the papers relating to the design and construction of Balfron. Reading through them I am struck by just how experimental the designs were. On the completion of Balfron Tower in 1968, Goldfinger and his wife moved into a flat on the 25th floor for two months.

In the same year the Guardian quotes Goldfinger saying, “I want to experience, at first-hand, the size of the rooms, the amenities provided, the time it takes to obtain a lift, the amount of wind whistling around the tower, and any problems which might arise from my designs so that I can correct them in the future.”

The architect as tenant

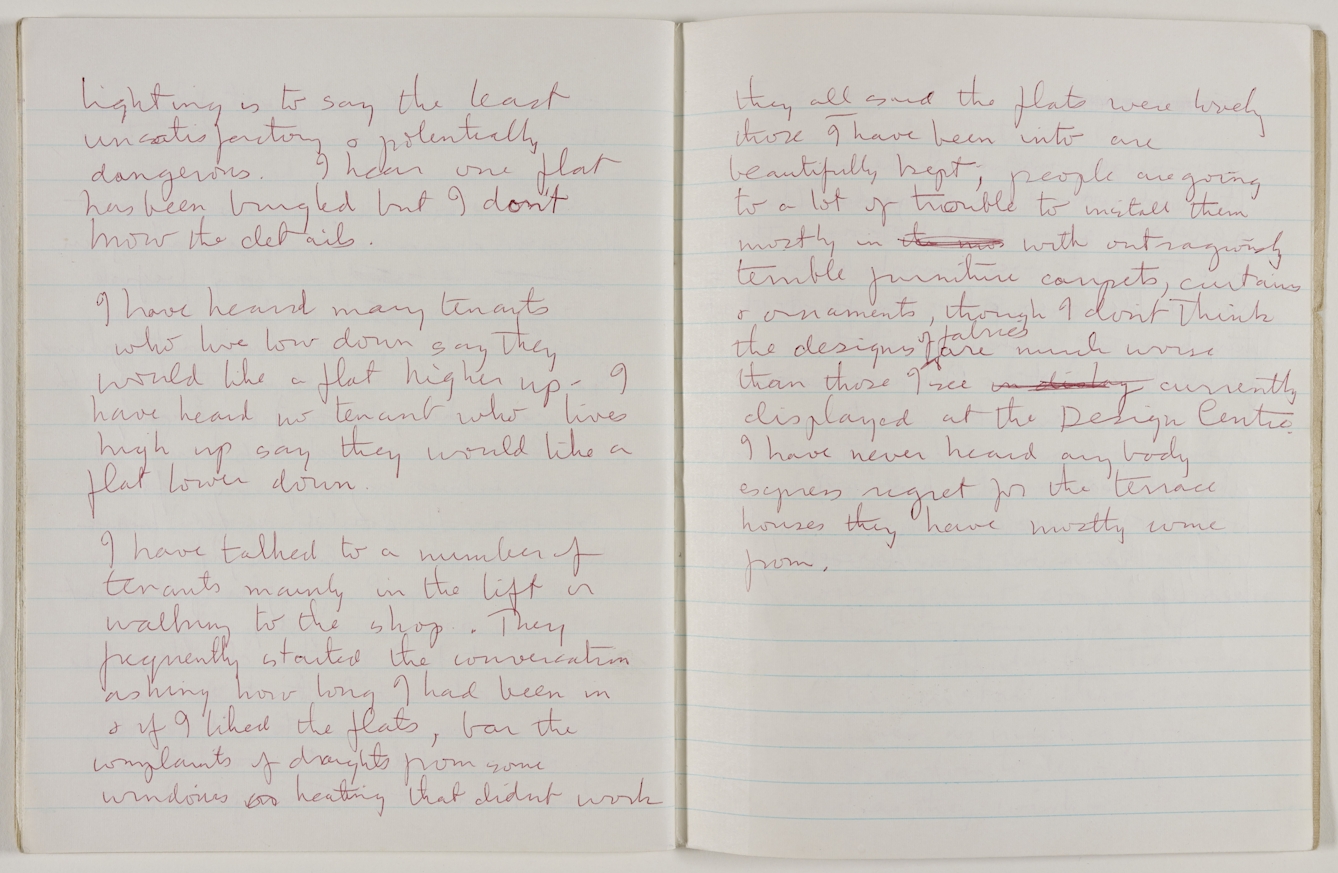

It wasn’t just the architecture that was under investigation during his tenure. It was also a response to the criticism that high-rise buildings were impersonal and unsuitable places to live, especially for families. The Goldfingers hosted receptions in their flat and encouraged residents to share their experiences of the flats.

Ursula Goldfinger recorded some of these encounters in a diary she kept of their stay: “I have talked to a number of tenants, mainly in the lift or walking to the shop. They frequently started the conversation asking how long I had been in and if I liked the flats; bar the complaints of draughts from some windows, heating that didn’t work, they all said the flats were lovely… I have never heard anybody express regret for the terrace houses they have mostly come from.”

Ursula Goldfinger’s notebook from her time in Balfron Tower, 1968.

It’s hard to tell how honest the residents felt that they could be with the architect and his wife, but it’s true that the GLC made efforts to preserve community relationships: lists show the residents of the new towers came from neighbouring streets.

It is likely that Goldfinger’s stay at the top of Balfron Tower inspired arch-chronicler of 20th-century dystopia J G Ballard. In his novel ‘High Rise’, the architect of a fictional high-rise development lives in the penthouse “hovering over” the inhabitants, while they descend into chaos and savage violence.

From social housing to private profit

Balfron Tower and many other developments like it have been the setting for a large number of films and television series. Many reinforce the idea that buildings like these represent an inhuman, squalid environment, shaping wider perceptions of such buildings and the people that inhabit them.

High-rise living is complex – and not suitable for everyone. Many residents struggled. One early occupant of the Pepys Estate in Deptford describes her difficulties in adjusting to life in the sky: her husband suffers a nervous breakdown, she can’t leave the children. In the wake of Grenfell Tower, attention is now paid towards people living in high-rises.

This image shows the view from one of the flats in Balfron Tower. It is from a film in which former council tenants describe what living in – and leaving – the tower means to them.

Balfron Tower’s more recent history tells a story – of housing, architecture, community and health – in the 21st century. The Grade II-listed structure, desperately in need of refurbishment, was passed from council ownership to a local housing and regeneration association.

Despite early hopes that the flats would be brought up to the ‘decent homes’ standard, Balfron Tower is now being refurbished for the private market, with the loss of all social tenancies.

Enforced relocation, lack of agency and poor engagement with residents by housing agencies and planners all take their toll on mental health. Refurbishment seems to offer better health outcomes, but the the quality of the design and the generous mandatory space requirements of state housing at this time provide an enticing prospect both for developers and councils alike.

I can’t forget the words of one resident of Balfron Tower, speaking in a film made by artist Rab Harling before the residents were moved out: “You don’t get a choice about where you live, really, and it can influence so much about what you become.”

Back in North Kensington, the government and the local council have promised funding to refurbish the Lancaster West Estate and create a “model for social housing in the 21st century”. Meanwhile, residents of other local estates, like the Silchester Estate, wait to hear what the future holds for them.

I wonder if this is a turning point, a readjustment of priorities which, if we return to Dickens, sees homes that are “decent and wholesome” – and healthy for everyone.

About the author

Emily Sargent

Emily Sargent is Senior Curator at Wellcome Collection. She has curated numerous large exhibitions on a wide range of subjects, including 'Living with Buildings' (October 2018–March 2019), and exhibitions on human enhancement and the experience of consciousness.