The gentrification of a corner of Bermondsey leaves little clue to its history as one of London’s most squalid slums. Fortunately, intrepid 19th-century writers exposed the short, sickly lives of those who endured these appalling conditions, finds Emily Sargent.

How slums make people sick

Words by Emily Sargentaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

On an ordinary commute home from Wellcome Collection’s offices on the Euston Road last year, I picked up a copy of the Evening Standard on the train as it pulled out of London Bridge. It was a Wednesday – the property issue – and inside I found a feature showcasing the design details of an exquisitely restored, industrial, loft-style apartment that was new to the market.

Among the exposed-filament light fittings and stainless-steel surfaces was a more unusual feature that caught my eye.

The building bore a blue plaque commemorating the area known as Jacob’s Island, and the Folly Ditch that encircled it, described by Charles Dickens as a “muddy ditch, six to eight feet deep”, and noting that it was in the ooze of this ditch that Bill Sikes met his death in Dickens’s novel ‘Oliver Twist’.

Artist Gustave Doré produced a series of illustrations of the extremes of London life in the 19th century, to accompany journalist Blanchold Jerrold’s accounts of the city. “The journey between Vauxhall, or Charing Cross, and Cannon Street, presents to the contemplative man scenes of London life of the most striking description. He is admitted behind the scenes of the poorest neighbourhoods; surveys interminable terraces of back gardens alive with women and children…”

Charles Dickens was both inspired and outraged by the conditions of London’s poor he observed while researching his novels.

In the 19th century, slum housing posed a serious threat to the health of people living in Britain. The Industrial Revolution had brought work, and with it large numbers of workers, from the countryside to city factories.

This shift in population placed a huge strain on housing in London and other industrial centres across the UK, with large numbers of people forced to live in overcrowded dwellings with poor or little sanitation or drainage, exposed to damp and disease.

The scale and scope of the problem ultimately led to the clearance of many of these slum residences, but it also inspired writers, artists, philanthropists and doctors to draw out the voices of those living in such profound squalor.

Writing in the preface to the Cheap Edition of ‘Oliver Twist’, published 13 years after it first appeared as a serial, Dickens reinforces his concern for the residents of Jacob’s Island, and other places like it.

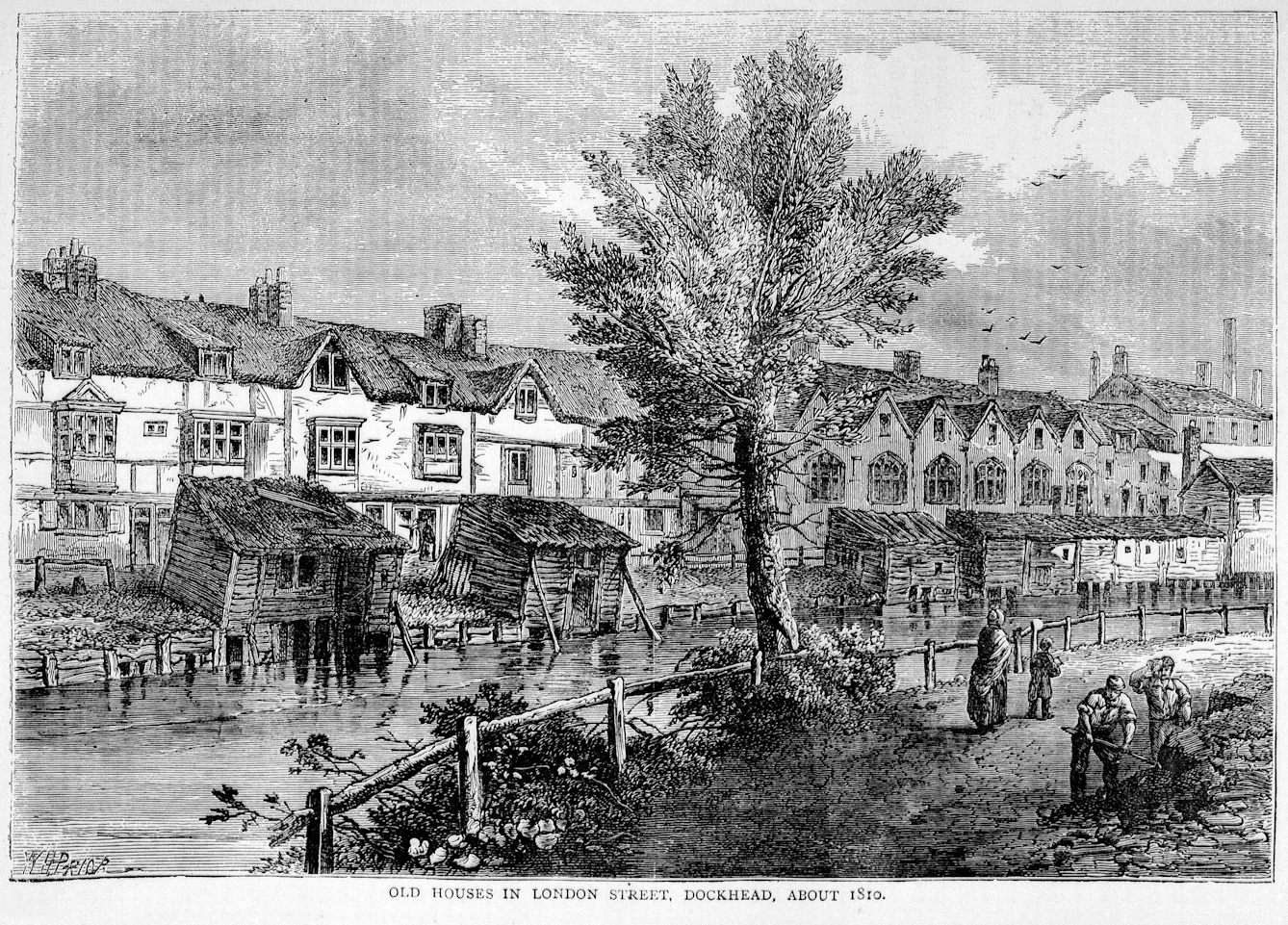

This illustration shows the area known as Jacob’s Island, described by Dickens in Oliver Twist: “Crazy wooden galleries common to the backs of half-a-dozen houses, with holes from which to look upon the slime beneath… rooms so small, so filthy, so confined, that the air would seem to be too tainted even for the dirt and squalor which they shelter.”

Faced with criticism from magistrate and former Lord Mayor Sir Peter Laurie, who dismissed Dickens’s descriptions of Jacob’s Island as having “only existed in a work of fiction”, Dickens states his belief that “nothing effectual can be done for the poor in this country until their dwelling places are made decent and wholesome”.

According to Dickens, housing is the first priority in helping the needy; only after that has been properly addressed can other support usefully follow.

Attempting to survive

Sitting in the hushed environs of the Rare Books & Music Reading Room at the British Library, leafing through the beautifully bound handwritten manuscript of the preface to the Cheap Edition of ‘Oliver Twist’ – now on display in ‘Living with Buildings’ at Wellcome Collection, it’s hard not to be moved. It’s hard too, to imagine what Dickens would make of that blue plaque.

It wasn’t only Dickens who took inspiration from the squalor of Victorian London. American writer and adventurer Jack London travelled to London to investigate the “human wilderness” of the East End.

Exchanging his fine clothes for those of “other and unimaginable men”, he lived alongside the thousands of working-class Londoners attempting to survive in the city at the turn of the 20th century.

His vivid and detailed accounts of those he encountered during his stay were published in a book entitled ‘The People of the Abyss’ (1902), illustrated by photographs taken of families huddled on benches; queues for workhouses and refuges; the homeless sleeping in Green Park or in the shadow of Spitalfields. Those who did have somewhere to live were not much better off.

London describes how:

“The sanitation of the places I visited was wretched. From the imperfect sewage and drainage, defective traps, poor ventilation, dampness and general foulness, I might expect my wife and babies speedily to be attacked by diphtheria, croup, typhoid, erysipelas [a bacterial skin infection], blood poisoning, bronchitis, pneumonia, consumption and various kindred disorders.”

In devastating terms, he acknowledges that the inevitable early death awaiting any such family would solve the problem of feeding, clothing and raising children in such desperate conditions. London invites us to “observe the beauty of the adjustment”. It makes for heartbreaking reading.

In the final chapter, titled ‘The Management’, London questions how the British Empire, at the height of its power, could neglect the needs of so many at home.

The National Philanthropic Association campaigned for improved sanitation and the provision of public baths and wash-houses. Inspections of homes and lodgings revealed poor ventilation and inadequate sanitation as well as “intermediate mingling of the sexes”.

The building doctors intervene

Some doctors of this period were so convinced of the role housing played in illness that they expanded their practice to include patient’s homes. They were called on to diagnose, treat and heal the architectural body as well as the patient’s.

Wellcome Collection’s library yielded a fascinating find – a diminutive publication titled ‘Dangers to Health: A pictorial guide to domestic sanitary defects’ published in 1879 by a Dr T Pidgin Teale.

Teale was one of a number of such ‘building doctors’ and his book describes in great detail the many and various ways in which drainage defects, poor ventilation and unsanitary buildings contributed to ill health, all accompanied by rather charming illustrations of both interior and exterior details.

One drawing shows a row of terraced housing, seemingly being assaulted on all sides by arrows representing the unsanitary air rising from beneath. Titled ‘Terrace of the future on refuse of the past’ the illustration takes task with ‘speculating’ developers who have built on rubbish dumps and night-soil (sewage) heaps, and celebrates a recently passed bylaw that outlawed this practice.

The caption “Terrace of the future on refuse of the past” refers to dwellings built on rubbish or “night soil” (sewage) heaps.

Teale, like Dickens and London, tells the personal stories of the people whose homes were making them ill, threatening their health and often their livelihood.

One description tells of a young woman training to be a singer, who was suffering from a chronic sore throat and loss of voice. Further enquiry into the conditions at home revealed that two children had died of diphtheria, and the kitchen floor was damp and ‘offensive’ from the overflow of the cesspool.

Complaints were made to the landlord’s agent, to no avail. The woman’s husband dared not to complain directly to the landlord, who was also his master, for fear of being dismissed from his position of head gardener.

Teale pulled no punches in his condemnation of landlords who placed profit ahead of their responsibilities to provide safe housing to their tenants, stating “he is committing little short of manslaughter if, by refusing to rectify sanitary defects in his property, he saves his own pocket at the expense of the health and lives of his tenants”.

It’s a statement that remains depressingly relevant as housing security, safety, affordability and responsibility still jostle uncomfortably in today’s rental market.

But I wanted to find out more about how 19th-century society – and architecture – responded to the undeniable health impacts of poor housing at this time, especially amongst the huge numbers of factory workers up and down the country. My first stop on this journey was Saltaire, a small and charming town near Bradford, West Yorkshire.

About the author

Emily Sargent

Emily Sargent is Senior Curator at Wellcome Collection. She has curated numerous large exhibitions on a wide range of subjects, including 'Living with Buildings' (October 2018–March 2019), and exhibitions on human enhancement and the experience of consciousness.