Dr Edward Clarke claimed that females who were educated alongside their male peers were developing their minds at the expense of their reproductive organs. His biological theory of education may seem shocking but in the late 19th century it proved very popular, and the vitalist thinking at it's heart influenced the language and treatment of women's health, as well as education.

The law of periodicity for menstruation

Lalita Kaplishaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Article

In 1873 Dr Edward Clarke, a physician and prominent board member at Harvard Medical School, published 'Sex in Education; or, a Fair Chance for Girls'. Clarke claimed that girls who were educated alongside boys in school and college were developing their minds at the expense of their reproductive organs.

He suggested that the pain girls experienced during their periods was an early sign of damage to the reproductive system, and even if there was no pain during puberty, later in life they could find themselves unable to bear children.

Clarke based his ideas on the ancient medical theory of vitalism, which asserted that in order to function properly, the body needed to maintain a certain level of vital force or energy. In vitalist terms, problems with the body, such as disease, occurred when the vital force was depleted.

Victorian schoolgirls in a needlework class, an appropriate form of female eduction according to the Law of Periodicity because it did not require the same vital energy as academic study.

Clarke argued that during puberty girls needed to reserve their vital force for developing reproductive organs instead of diverting it towards strenuous mental activities such as studying, especially at the same rate as boys. His solution - The Law of Periodicity - proposed that girls should take an easier course of study during adolescence. He suggested that “during every fourth week, there should be remission and sometimes an intermission of both study and exercise” in order to minimise any risk to the reproductive organs during menstruation.

According to vitalist theory, men were also affected by depletion of the vital force. Young men in particular, were warned against excessive masturbation and sexual activity that would drain vital force and affect the performance of other bodily functions including mental activity. But women, whose primary function was seen as reproduction, were expected to sacrifice education for sexual health and for the sake of future generations.

The question of rest

Clarke’s ideas did not go unchallenged. His critics pointed out that he had no problem with women doing housework all month or working in factories or shops, and perhaps his objection to women in education had something to do with increasing numbers of women applying to study at Harvard Medical School, where he was a board member. But Clarke argued that mental effort needed more vital force than housework, and labouring women “work their brains less” so their reproductive organs were not at risk.

In 1874, physician and researcher Mary Putnam Jacobi won Harvard’s Boylston medical prize for her essay 'The Question of Rest for Women During Menstruation'. Jacobi submitted her essay anonymously and the prize committee were so horrified when they found out she was a woman that they refused to publish her work, although they gave her the prize money. Fortunately her father was a publisher so her work was published anyway.

Middle-class Victorian women were encouraged to take lots of rest in order to direct vital energy to their reproductive organs.

Jacobi questioned 268 women about their menstrual cycle and found that while nearly all experienced pain at some time in their lives, there was no correlation with their level of education or length of study. Although she included both paid and unpaid women in her survey, she excluded others, such as “negroes who for our purposes may be excluded from the reckoning.” While advocating for white, middle-class women, Jacobi made her arguments within the same eugenic framework as Clarke.

Despite challenges from some people such as Mary Jacobi, Clarke’s book was enormously popular in America and Europe, running to 17 editions in 13 years. His ideas were supported by physicians and educators. Physician John Harvey Kellogg, who had his own theory of "biologic living", wrote that during her period a woman “should be relieved of taxing duties of every description and be allowed to yield herself to the feeling of malaise which usually comes over her at this period, lounging on the sofa or using her time as she pleases” (1891).

The new woman on washday, 1901. Modern women, especially those who sought education, were seen as a threat to the traditional male and female spheres of work and life.

Many women, then and now, may find the idea of “lounging on the sofa” for a week every month tempting but, as Clarke’s critics pointed out at the time, it’s a luxury that few can afford. Both Clarke and Kellogg intended their advice for a certain kind of wealthy woman.

Middle class white women were stereotyped as delicate and at the mercy of their reproductive system. But by the last quarter of the 19th century the ‘new woman’ aspired to go to college and earn her own living. The response from much of the medical establishment and the popular press to this threat to male spheres of working life was to argue that women were best suited to domesticity not just because of tradition but because of their biology.

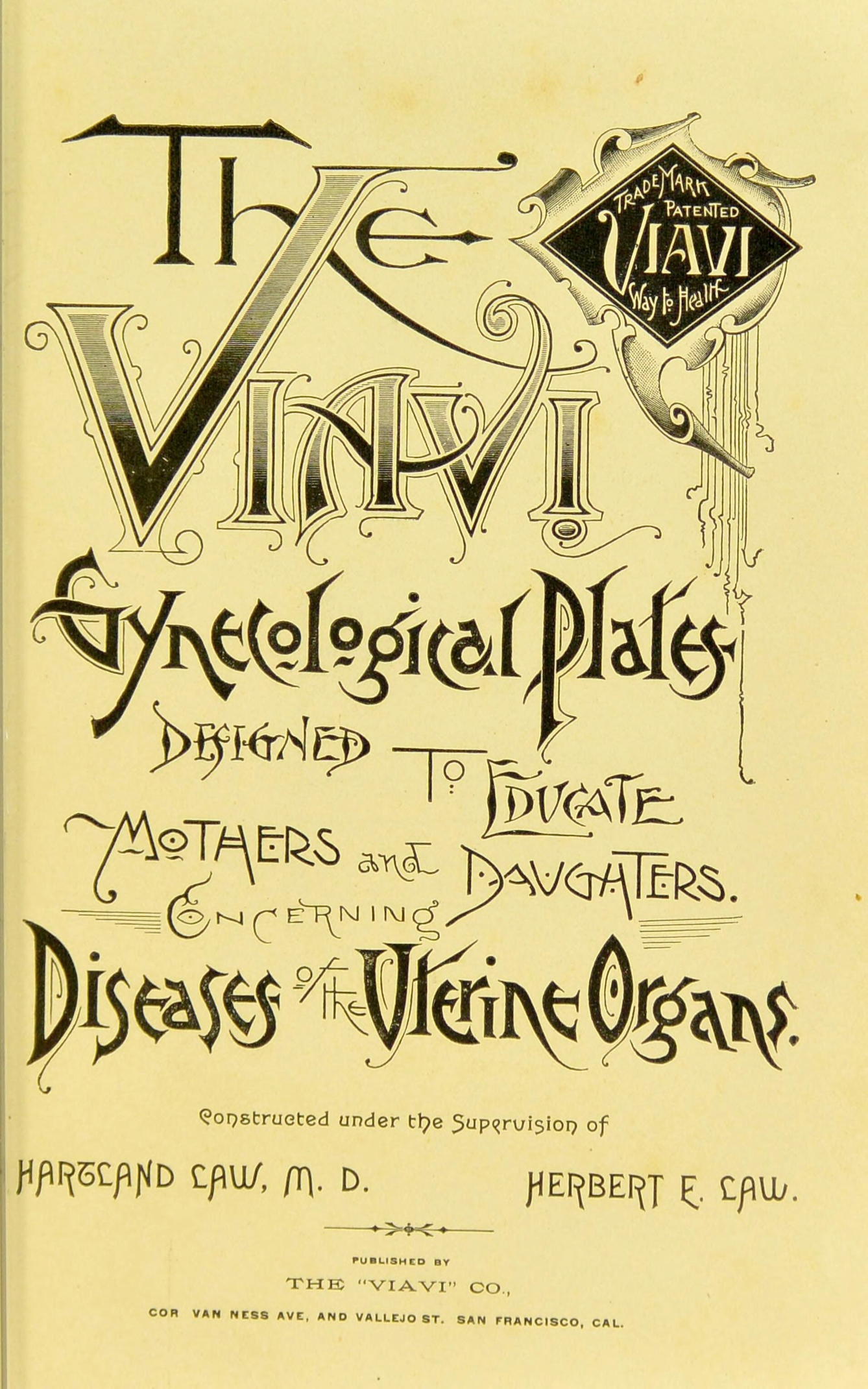

The Viavi System

Conflicting views about the role of women in society and their health at the end of the 19th century contributed to the success of the Viavi System, a commercial health product range aimed at the wealthy middle class woman.

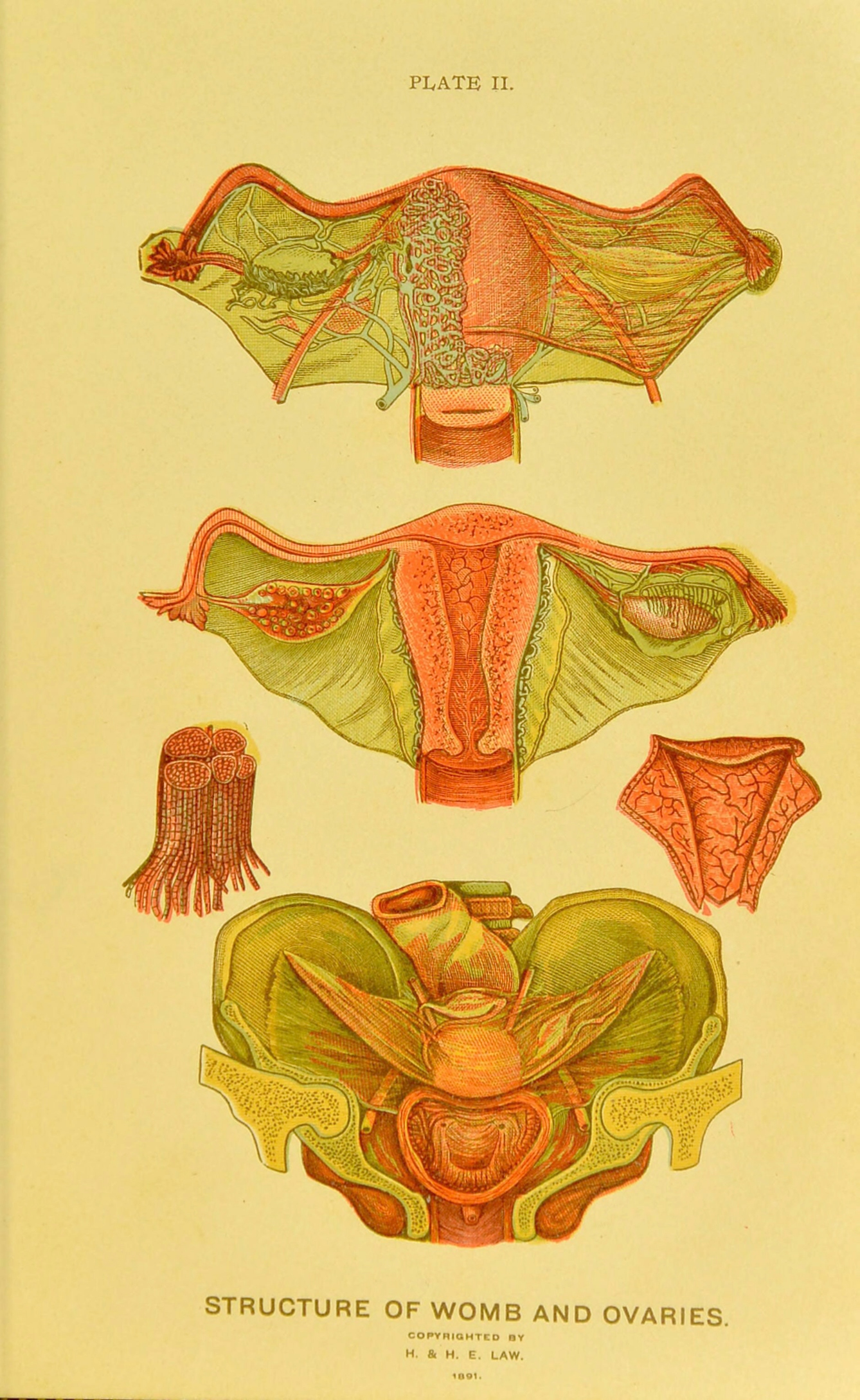

The Viavi Gynecological Plates (1891) were both an educational aid and a sales technique for selling the Viavi System of health care to wealthy women.

The Viavi system was developed by two brothers, Hartfield and Herbert Law, in San Francisco in the 1890s. It consisted of several products, including capsules, cerate (an ointment) and ‘tablettes’. All of the products were made from the same “natural vegetable materials” and used to help restore the natural balance and allow the body to heal itself.

The products were sold door to door by a team of trained female ‘specialists’, who brought with them a large impressive display book called the 'The Viavi Gynaecological Plates'. The sympathetic female specialist was there to educate and to share the customer’s concerns, according to the 'Viavi Hygiene' book, which had several chapters on menstruation: “The mutual confidence that grows up between a sufferer and a Viavi representative is beautiful”.

The Viavi System appealed to the modern woman's desire to educate herself about her body and take control of her own health, but in order to sell its expensive products, the system in effect pathologised menstruation as a potentially debilitating phenomenon that needed careful management.

The Viavi plates contained expensive and detailed illustrations of female anatomy, along with 'medical symptoms' and thier causes, which gave their sales 'specialist' some medical authority.

Management of your menstruation and reproductive system came in the form of a routine in which capsules were inserted in the vagina, cerate (ointment) was applied to the skin around the "afflicted area" and 'tablettes' were regularly consumed. Vaginal douches were advised in order to maximise absorption from the capsules. In addition, “Well ventilated sleeping apartments exposed to the sun’s rays, with judicious exercise in the open air, either walking, riding or playing tennis or croquet, but never to the point of exhaustion, and plain nutritional food, perfectly regular habits, early retiring and abundant sleep will greatly hasten the cure”

The female sphere

In reality the Viavi System had little effect, although the general advice about regular sleep, exercise and diet would have benefitted many of the women who purchased their expensive products. A firm of analytical chemists reported that the capsules “contain nothing but the extract of hydrastis (a traditional herbal cure) and cocoa butter”, but there was still the risk of of introducing infection into the vagina from regularly inserting capsules. Perhaps a greater danger was that the Viavi System actively discouraged women from seeking medical advice for potentially serious conditions.

In a society still dominated by separate spheres for men and women the (male) gynaecologist was often viewed with suspicion. The Viavi publications played on these concerns, saying: “Let a father reflect what it means to a girl to be submitted to an examination, even by a most considerate physician”, and they warned that medical interventions would be extreme: “a woman afflicted with any form of painful menstruation is in positive and imminent danger of a surgical operation, whether minor or capital, unless she adopts the Viavi System of treatment”. Significantly, the Viavi 'specialists' were all women, who could, with the Viavi System, defend her from the dangers of the medical profession.

In the Viavi System the causes of menstrual problems were mainly generic and did not mention medical conditions that might require a physician to diagnose them.

Ultimately the medical establishment reacted with several court cases in the UK and USA against the Viavi sales techniques and Viavi sales specialists were condemned for advising women with cancer and other serious conditions not to see a doctor.

Beneath its apparently progressive emphasis on educating women and giving them control over their own bodies, the Viavi System actually appealed to very conservative notions of female modesty, mistrust of mainstream medicine and, like Clarke's Law of Periodicity, the belief that female reproductive health depended on special care and limited activity in the wider world.

About the contributors

Lalita Kaplish

Lalita is a digital content editor at Wellcome Collection with particular interests in the history of science and medicine and discovering hidden stories in our collections.