A tattoo is defined as an indelible mark fixed upon the body by inserting pigment under the skin, and the earliest evidence of tattoo art dates from 5000 BCE. Across time and cultures, tattoos have many different forms and meanings.

The origin of tattooing

The phenomenon of tattooing was once widespread. In ‘The Descent of Man’ (1871) Charles Darwin wrote that there was no country in the world that did not practice tattooing or some other form of permanent body decoration.

The 19th-century German ethnologist and explorer Karl von den Steinen believed that tattooing in South America evolved from the custom of decorating the body with scars. Plant sap rubbed into the wounds to prevent bleeding caused discolouration of the scar. The resulting decoration could be regarded as a tattoo.

In his book ‘Missionary Travels and Research in South Africa’ (1857), David Livingstone wrote that many Africans tattooed themselves by introducing a black substance under the skin to cause a raised scar. North-American Apache and Comanche warriors rubbed earth into battle wounds to make scarring more visible and flaunt them within the tribe, while the pygmies of New Guinea treated infections by rubbing herbs into incisions in the skin, causing permanent scarring.

Such tales suggest that tattooing probably arose at various locations through bloodletting practices, scarification rituals, medical treatment or by chance. The popular assumption that tattooing had a single origin is discredited.

Charles Darwin wrote that there was no country in the world that did not practice tattooing or some other form of permanent body decoration.

Early and ethnographic tattoos

The earliest evidence of tattoo art comes in the form of clay figurines that had their faces painted or engraved to represent tattoo marks. The oldest figures of this kind have been recovered from tombs in Japan dating to 5000 BCE or older.

In terms of actual tattoos, the oldest known human to have tattoos preserved upon his mummified skin is a Bronze-Age man from around 3300 BCE. Found in a glacier of the Otztal Alps, near the border between Austria and Italy, ‘Otzi the Iceman’ had 57 tattoos.

Many were located on or near acupuncture points coinciding with the modern points that would be used to treat symptoms of diseases that he seems to have suffered from, including arthritis. Some scientists believe that these tattoos indicate an early type of acupuncture. Although it is not known how Otzi’s tattoos were made, they seem to be made of soot.

Other early examples of tattoos can be traced back to the Middle Kingdom period of ancient Egypt. Several mummies exhibiting tattoos have been recovered that date to around that time (2160–1994 BCE).

In early Greek and Roman times (eighth to sixth century BCE) tattooing was associated with barbarians. The Greeks learned tattooing from the Persians, and used it to mark slaves and criminals so they could be identified if they tried to escape. The Romans in turn adopted this practice from the Greeks.

MORE: Is shoegaze the loneliest genre of music?

‘Stigma’ – now meaning a distinguishing mark of social disgrace – comes from the Latin, which means a mark or puncture, especially one made by a pointed instrument.

Elaborately-tattooed mummies have been found in Pazyryk tombs (sixth to second century BCE). The Pazyryks were formidable Iron-Age horsemen and warriors who lived on the grass plains of Eastern Europe and Western Asia.

Tattoos in our collections

Plaster cast of the face of Tauque Te Whanoa, a Rotorua native, of the Arawa tribe showing Maori tattooing, ‘Moko’, performed with a serrated chisel and mallet with soot rubbed into the open wound to provide colouring.

Etching of a naked lady covered in floral tattoos standing in an open landscape.

Tattoo on a piece of human skin showing a male bust and a flower stem.

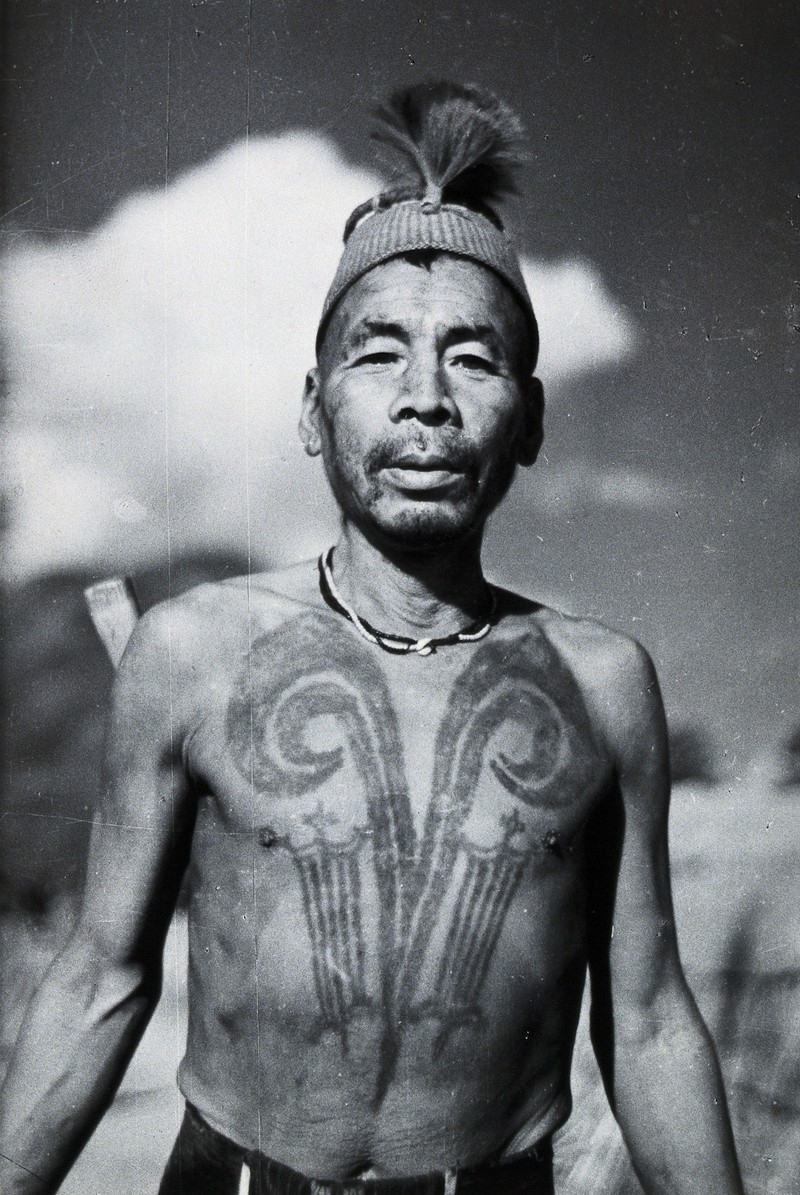

A Chang Naga man with head-hunter’s breast tattoo.

Dispersion theories of tattoos in different cultures

Tattooing may have dispersed from various places by way of migration and by nomadic peoples: the women of various gypsy tribes in India and the Middle East were specialised tattooists. For centuries they provided the tattoos for inhabitants of, and pilgrims to, regions as distant as Eastern Europe. The Scythians were similarly responsible for spreading tattooing from Siberia to Eastern Europe at the beginning of the Christian era.

Just as relationships exist between languages and dialects over vast areas, so there are similarities between tattoo designs found in regions and cultures far removed from each other. For example, throughout South-east Asia many men had a trouser tattoo that covered the area from the waist to knees. Among the peoples living in the Arctic and along the west coast of America, women tattooed their chin and cheeks with similar patterns.

It is human nature to exchange customs upon meeting, whether out of friendship, respect, envy or curiosity. The reciprocal imitation of tattoos by European sailors and South-Sea Islanders is a good example of this. The trade in prisoners who had been abducted by enemy tribes according to their custom caused tattoo designs to spread over large areas. Men of Borneo and Micronesia collected tattoos when visiting other tribes or islands.

The meanings of tattoos

The original meanings of many tattoos are lost. However, body decorations such as scarification, tattoos and piercings have always been an obvious means of distinguishing individuals within a group, and groups within a society. On a personal level, a tattoo is part of one’s identity.

Historically and culturally, tattoos have been applied both as marks of distinction (awarded for an achievement or signifying the transition to adulthood) and sources of shame (when applied punitively). Pain is an unavoidable aspect of tattooing and to many peoples its endurance was intrinsic to initiation.

At a tribal level, tattoos can indicate age, marital status, power and class, and outside the group they may distinguish friend from foe. In many tribes, women’s tattoos were symbols of beauty that simultaneously ensured they were of no value to neighbouring tribes.

Indigenous tattooing has all but disappeared globally, but in recent years tattoos have experienced something of a renaissance in Europe and North America. The reasons for this are not clear-cut, but it is apparent that tattooing in the ancient world has many things in common with modern tattooing.

I highly recommend tattoo anthropologist Lars Krutak’s TV series Tattoo Hunter, where he visits some of the most remote parts of the world, seeking tattoos from members of the few remaining authentic tribes. Also see Vanishing Tattoo, an online tattoo museum focusing on the search for the last authentic tattoos.

About the author

Amy Olson

Amy Olson is a Web Producer at the Wellcome Trust.