Public health campaigns often represent disability as the tragic outcome of failing to prevent disease by following health recommendations such as vaccination. Aparna Nair believes that such campaigns perpetuate prejudice against disabled people and are guilty of ableism.

Public health has, historically, had an uneasy relationship to disability. Many disabled people have experienced public health campaigns and services as disenfranchising and discriminatory. Public health has tended to work from within the medical model of disability, which pathologises disability as a medical and individual problem needing cure, prevention or rehabilitation.

Recent work in disability studies has critiqued the medical model of disability, pointing out the importance of the social, cultural and institutional factors that shape experiences of disability. But public health campaigns, past and present, draw on and reinforce wider social prejudices about disability to deliver their message, and are often ableist, biased towards able-bodied people.

Poor behaviour causes disability

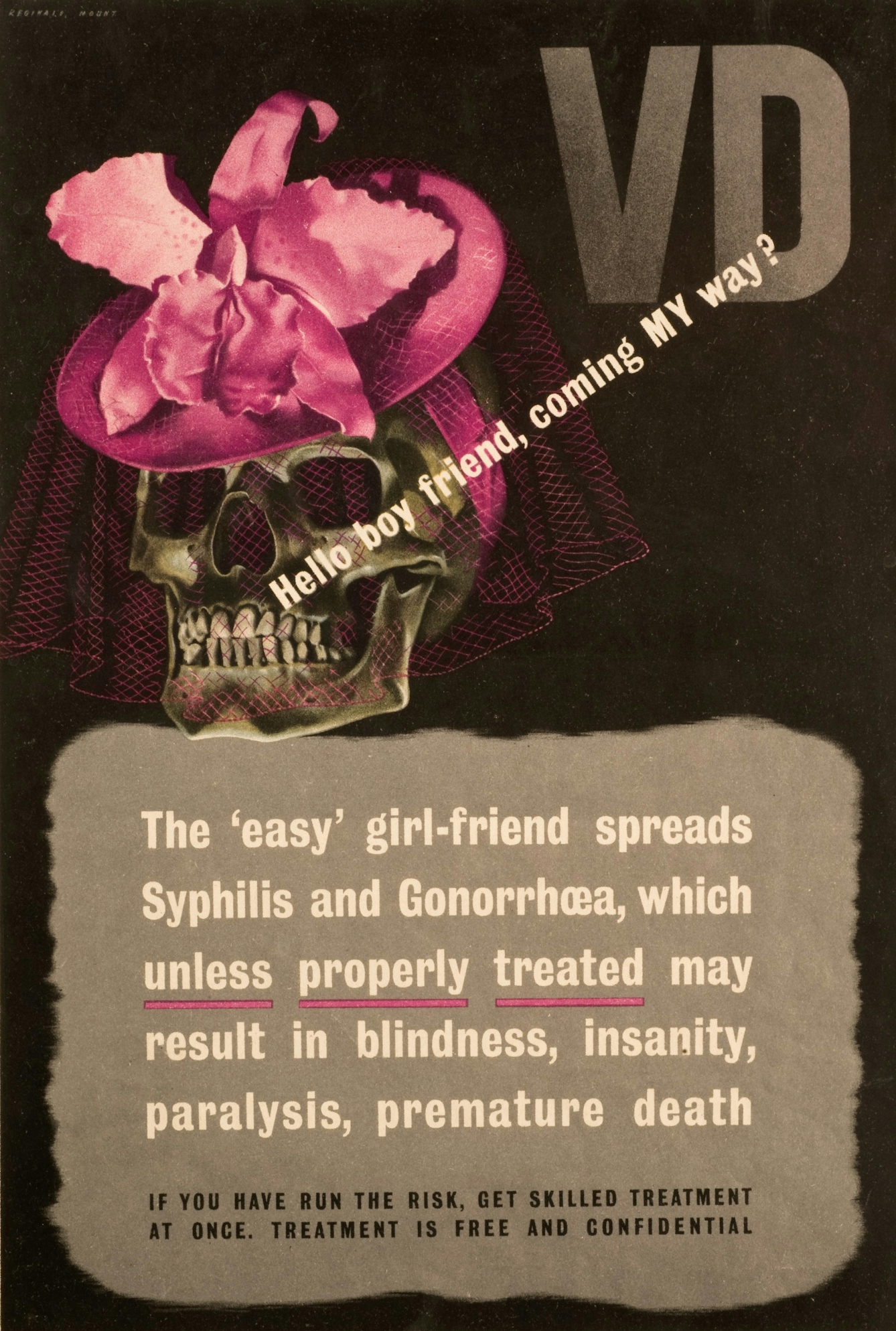

‘The Easy Girlfriend’, the poster part of an anti-VD campaign. Designed by Reginald Mount (1906–79) for the British Ministry of Information in 1943–4.

For example, many public health campaigns frame disability as the inevitable (and feared) consequence of undesirable or dangerous health behaviours. A 1940s British poster warning against venereal diseases (sexually transmitted infections) sends the message that when people have unprotected sex with ‘dangerous’ women, disability is the result. The poster clearly relies on social anxieties around ‘promiscuous’ women and existing fears about disability to reinforce its message about safe sexual behaviours.

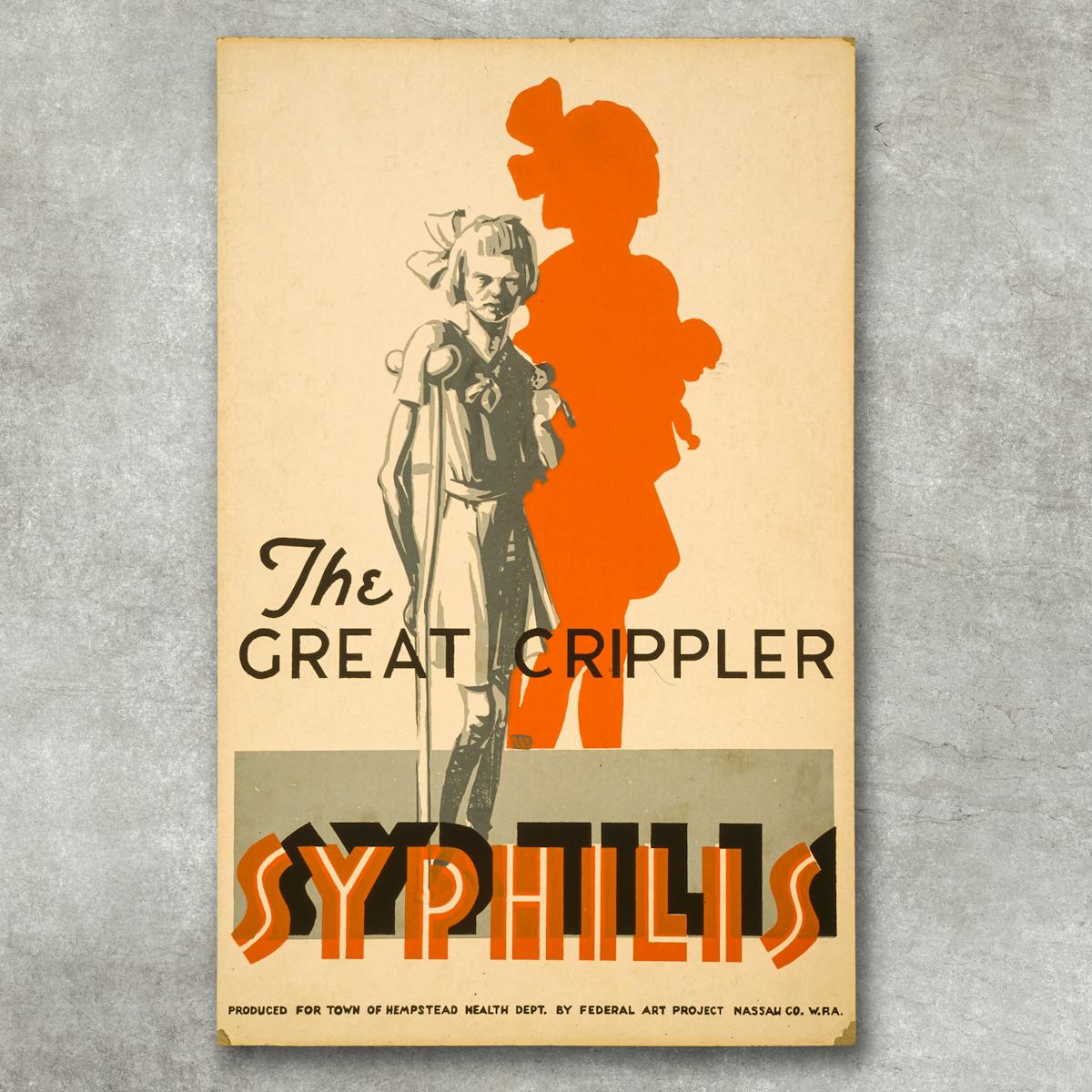

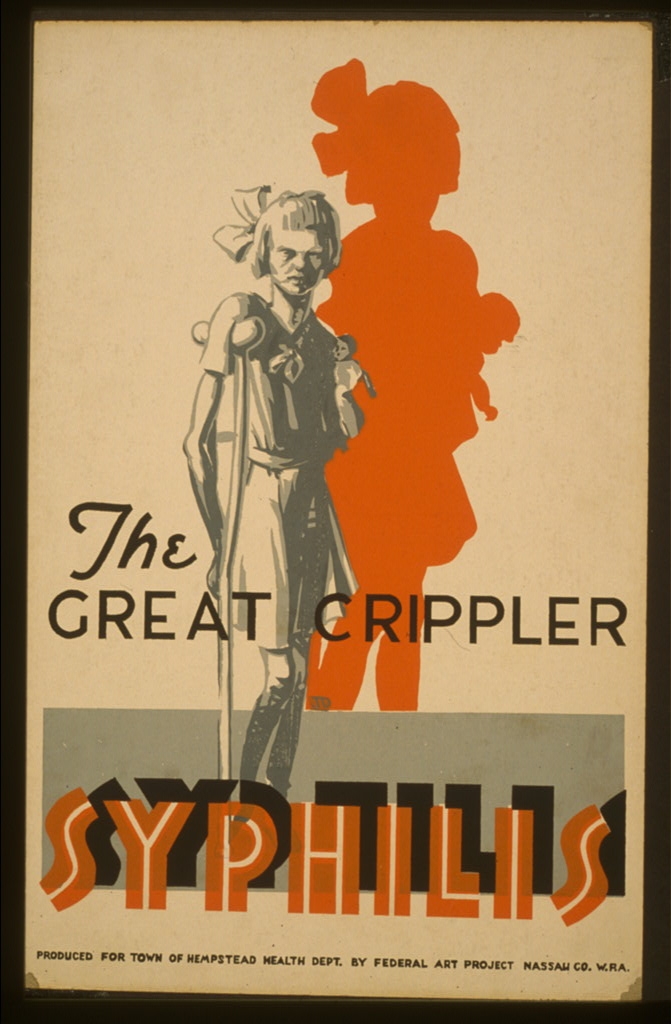

'The Great Crippler', poster produced for Hempstead Health Dept. in Nassau County, USA, 1936 or 1937.

This association of sexually transmitted infections with disability is not unique. Many public health campaigns frame disability as the inevitable (and feared) consequence of undesirable or dangerous health behaviours. An American poster from 1937 describes syphilis as “the Great Crippler” and depicts an unhappy young girl with crutches, suggesting that irresponsible sexual behaviour can lead to childhood disability in the next generation.

Public information poster about syphilis. By Refet Başokçu, Turkey, 1930s.

A 1930s Turkish public health poster on syphilis goes one step further. It uses striking images of congenital disability and facial disfigurement as deterrents, and also forms connections between sexually transmitted infections and criminality. Like the other posters, disability here is the ‘tragic’ consequence of unprotected sexual behaviour, not only for adults but also for children.

While these posters are clearly intended to deter certain health behaviours, they also ascribe shame to the disabled condition.

The ‘shame’ of disfigurement

Poster promoting vaccination against smallpox. Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic, 1930–39.

The use of disability to shape public health behaviours was not restricted to sexually transmitted infections. Smallpox vaccination campaigns often played on the fear of scarring and other disabilities. A Soviet poster from the 1930s shows a young man being vaccinated while the figure of an older man with a severely scarred face, his cane and blank eyes signifying his blindness, looms in the background.

The disabled man is a warning: his blindness and disfigurement are presented as the consequences of failing to vaccinate. Public health posters that use explicitly disabled figures to influence health behaviours only reinforce the existing stigma around disability. Historically, this stigma has contributed to disabled people being shunned, neglected, discriminated against or being socially isolated.

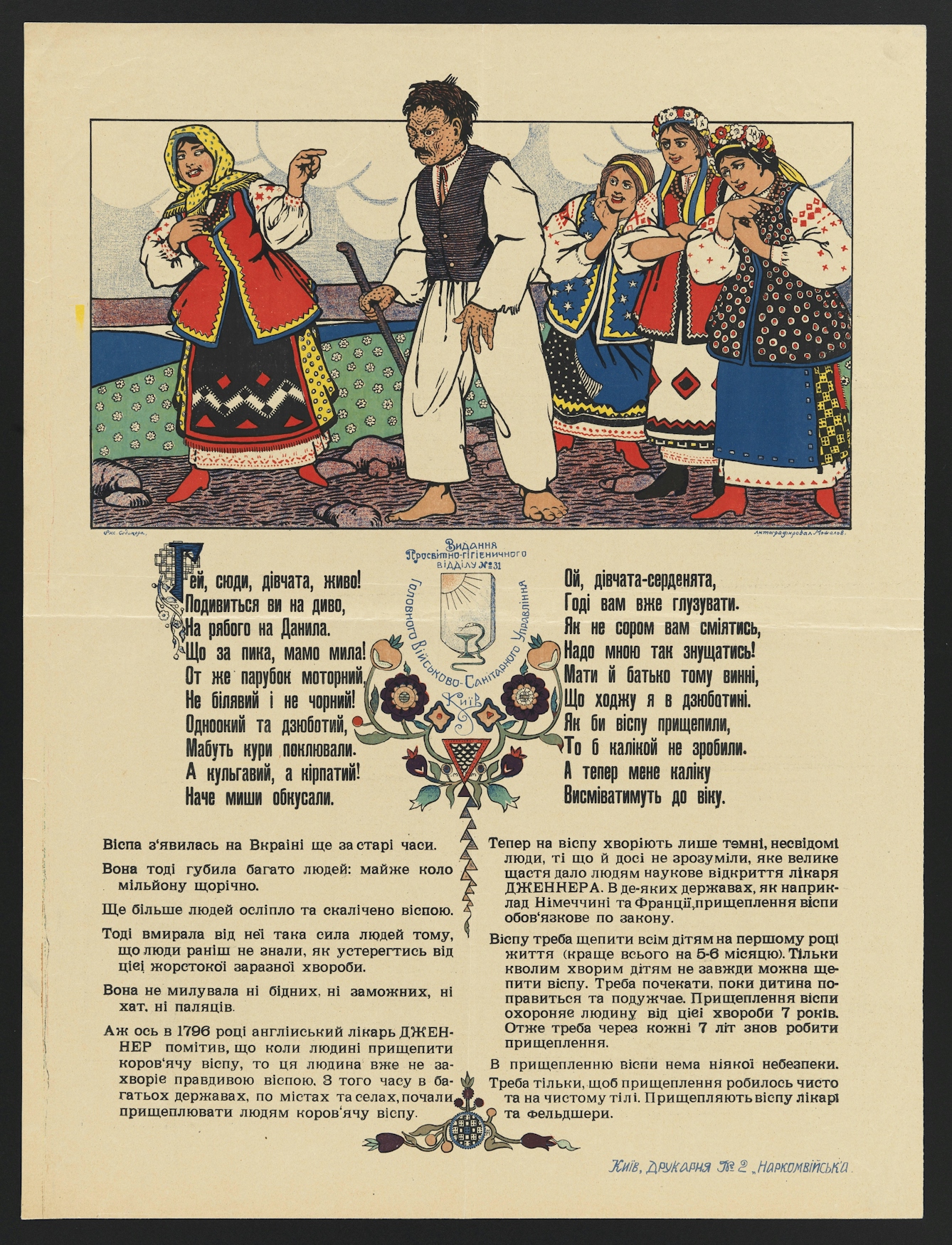

Smallpox vaccination campaign. By Sudimora, c. 1929. Kiev, Ukraine.

The public shaming of disability is exemplified by this 1929 Ukrainian poster, which uses the threat of social isolation and ostracism resulting from smallpox to encourage vaccination. Four women stand around a scarred, blind man, mocking him: “Look at Daniel! He has a remarkable face, not beautiful! He looks as if hands have torn pieces out of his face, or as if a mouse has bitten holes in it.” The poster defines Daniel by his disability, but it goes so much further: his disabilities render him a social outcast, a laughing stock, and sexually undesirable.

'Reward-Recompense $1000' poster, designed by René Gauch for the World Health Organisation, pre-1980.

Disability continued to be used in public health campaigns to elicit fear, shame and guilt throughout the 20th century. The striking abstract design of a 1980 World Health Organisation poster offering a reward for “the first person reporting an active smallpox case resulting from human to human transmission” still manages to allude to the facial disfigurement and scarring that often resulted from smallpox.

Polio and parental guilt

'Prevention is better than cure'. Poster for a polio vaccination campaign, France, 20th century.

Perhaps no other infectious disease is as closely linked to disability in public health campaigns as polio. Polio was also known as “infantile paralysis” until the mid-twentieth century because it was traditionally associated with paralysis and deformity in young children, although it did not impact children alone.

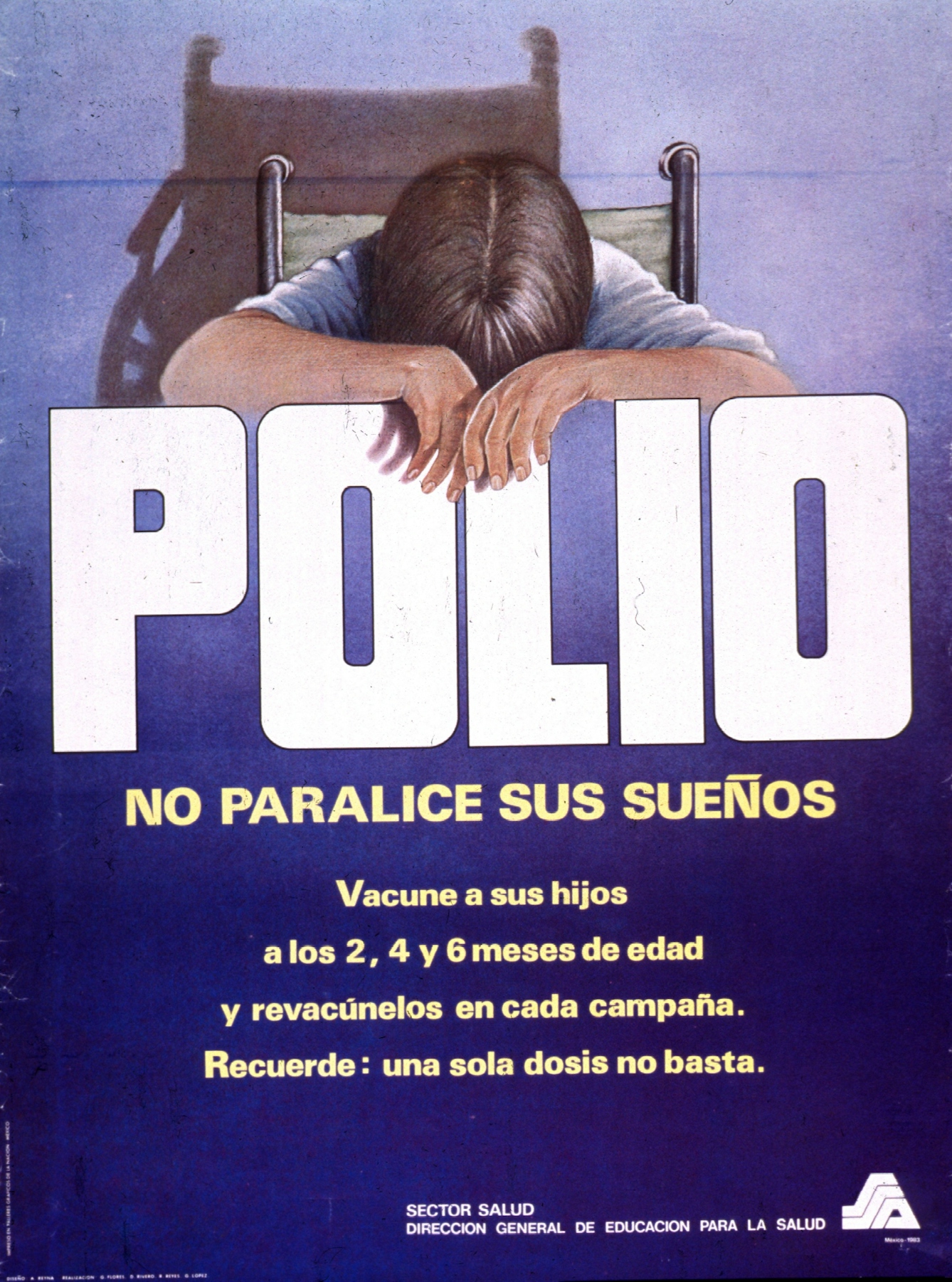

'Polio: don't paralyse his dreams', poster produced by Sector Salud, Dirección General de Educación para la Salud, Mexico, 1983.

Posters warning against the spread of polio routinely focused on parents as the ‘cause’ of their children’s disability. The text of a 1983 Mexican poster urges parents not to paralyse the dreams of their children by neglecting vaccination. The child in the poster is hunched over in a wheelchair and is the very epitome of despair and abjection. The poster frames childhood disability as a profound ‘tragedy’.

![Poster showing two children with disabilities and another receiving a vaccine. Next to the two children with disabilities is the text: 'THESE CHILDREN WERE NOT PROTECTED AGAINST POLIO.' Next to the image of the child being vaccinated is the text: 'PROTECT YOUR CHILD WITH ORAL POLIO VACCINE. GET INNOCULATED [sic] NOW!'](https://images.prismic.io/wellcomecollection/84639ee0-754a-491b-9451-d2c13061ebda_Image_8.jpg?w=1000&auto=compress%2Cformat&rect=&q=100)

Vaccination campaign poster published by the Division of Health Education, Nairobi, Kenya, c. 2000.

In a Kenyan poster for a polio vaccination programme in 2000, photographs of two unsmiling disabled children appear under the stark heading: “These children were not protected against polio”, implying to parents that disability was the cost of failing to protect their children through vaccination.

Despite the diverse origins of these public health campaigns, in time and place, the representations of disability remain the same. Not only is disability a medical ‘problem’ to be prevented, treated or cured, it is also framed as the consequence of individual behaviour, the result of moral failures, or as the neglect of parental duties.

Worse, these posters ascribe undeniably negative associations to disability: disability is tragic, and disabled people are to be pitied. In short, they reinforce the medical model of disability. And in the 21st century, public health campaigns continue to use disability to instil fear and shame in order to drive certain health behaviours. An American anti-tobacco video from 2016, the camera draws in on the face of a man disfigured by mouth cancer as a warning against the use of chewing tobacco.

Disability is a part of the spectrum of human difference, and disabled people are so much more than the consequences of other people’s bad luck or bad choices. We deserve better than to be held up as ‘lessons’ or warnings for non-disabled people.

About the author

Aparna Nair

Dr Aparna Nair is an assistant professor in the Department of History of Science at the University of Oklahoma. She works on disability, medicine and colonialism in India in the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as disability in popular culture and the experience of epilepsy in South India.