For centuries the human race has been prey to a variety of parasitic worms and lice. And not only do we have a long history as unwilling hosts, it seems that our disgust and embarrassment is also nothing new.

Recent public health scares in the USA and Europe, along with the personal experiences of millions of parents of young children, demonstrate that parasites continue to be a threat to human health and wellbeing.

Not surprisingly, parasites are a problem with a long history, as medieval archaeological evidence proves. Excavations of medieval latrines have demonstrated that intestinal parasites were a common complaint, while bodily remains prove that even the very rich were not exempt. Richard III was infected with roundworm when he died at Bosworth and King Ferdinand of Naples (1467–96) had both head and pubic lice.

Faced with such evidence, we tend to assume that although medieval people suffered from the same complaints as us, they were less bothered by them. In fact, medieval people shared our disgust and were far from passive in their approach to this medical problem.

Purgatives and personal grooming

Medieval attitudes to parasites were shaped by medical ideas prevalent at the time. We now know that parasites are usually transmitted by human contact or by infected food, but medieval doctors believed that they spontaneously generated in ‘corrupt matter’.

Gilbert the Englishman (c. 1180–1250) wrote that “worms of various shapes are engendered in a man’s guts”, a process which was believed to occur when those organs contained an excess of phlegmatic humours, which might be produced by overeating or by eating the wrong foods. So worms were treated using bitter, purgative plants such as wormwood or gentian, which would both kill the worms and expel them by provoking a nasty bout of diarrhoea.

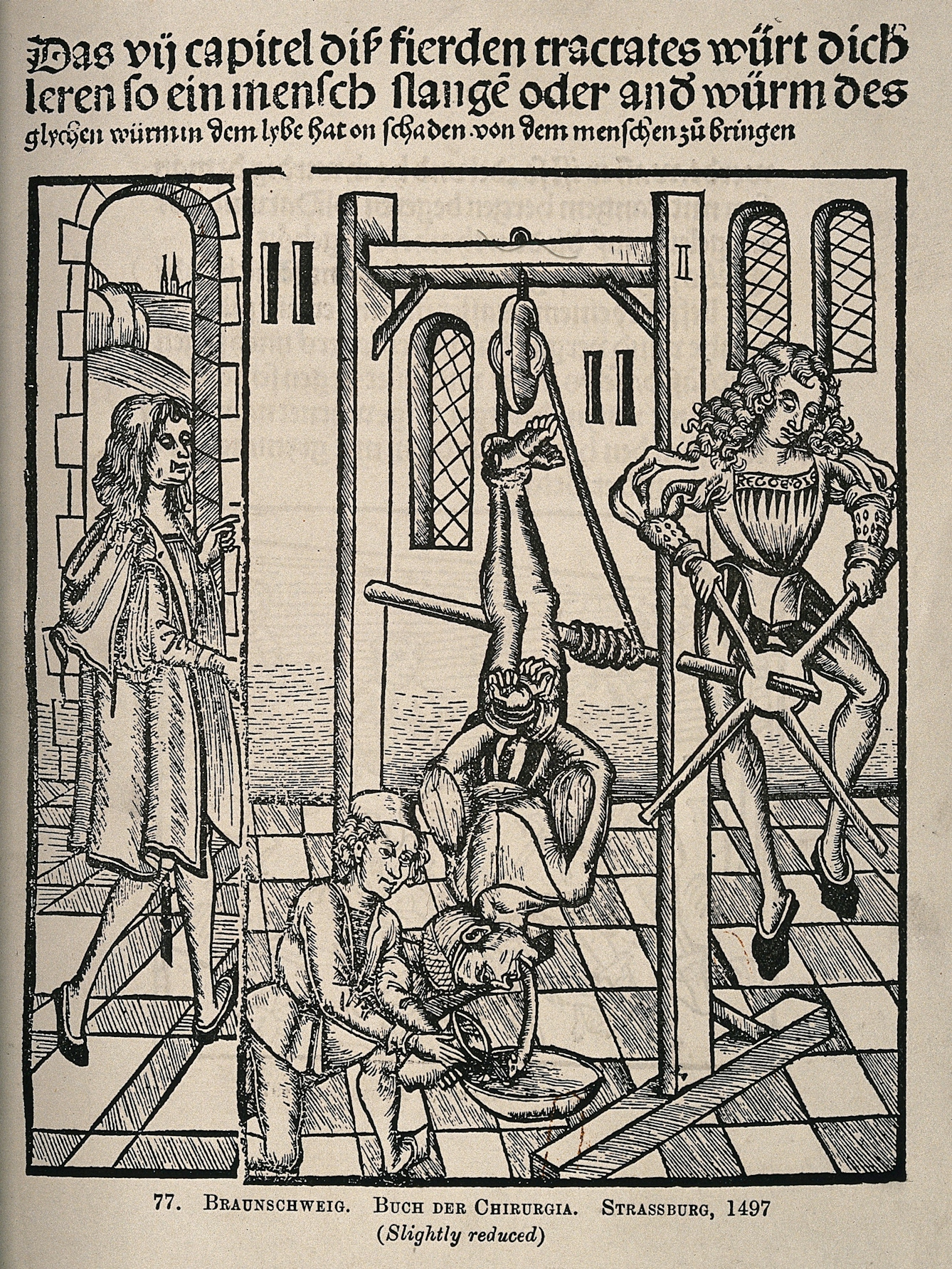

This worm evidently required more aggressive treatment than a mere purgative.

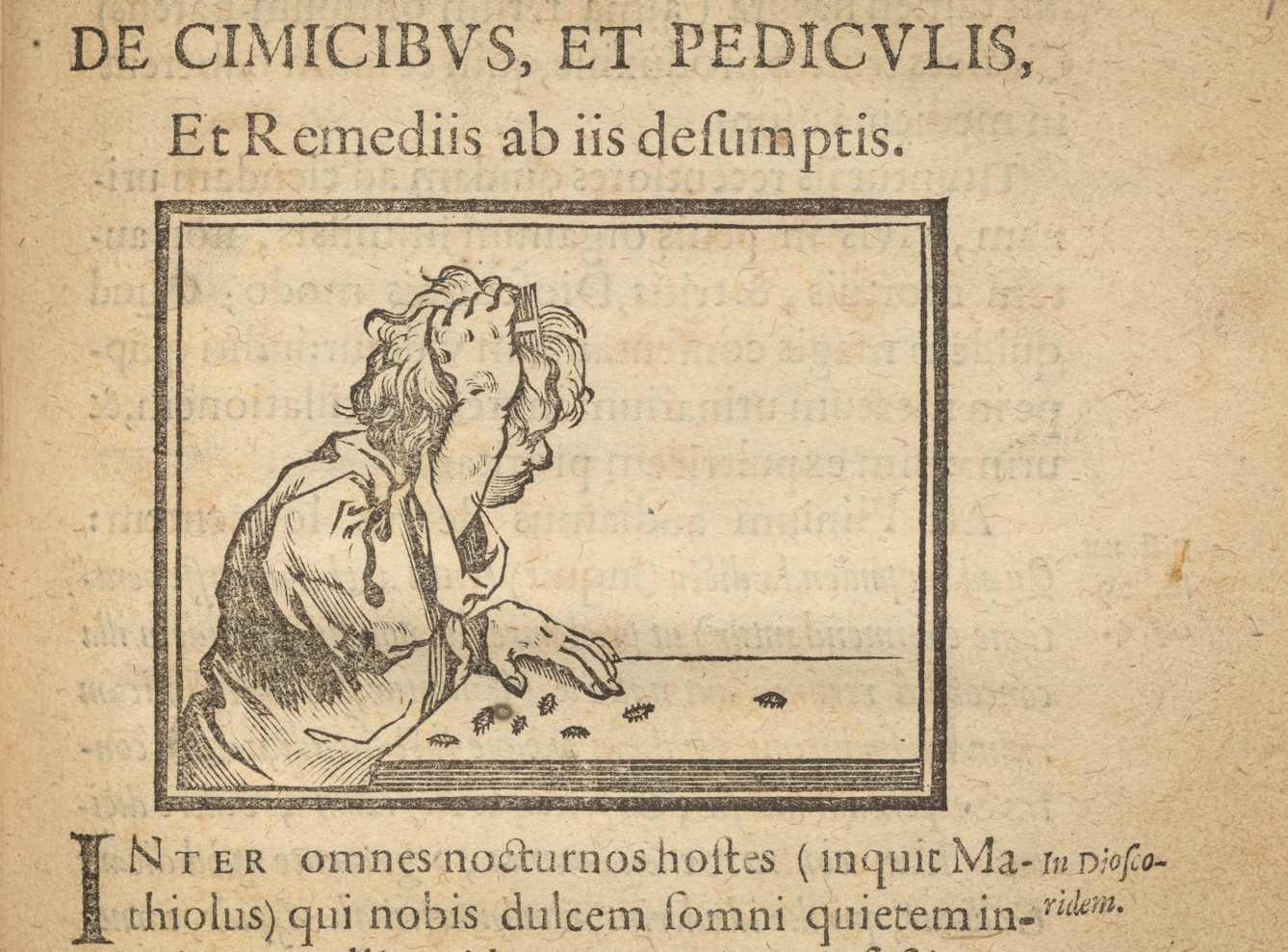

Nits and lice seemed to grow in dirt and bodily secretions, both in the hair and on the skin. They could be killed with ointments, many of which contained noxious substances such as mercury. Personal grooming was also important: treatments often included washing, and most medieval combs had a fine-toothed section similar to a modern nit comb.

Women were often responsible for delousing their loved ones. In 14th-century Montaillou, for example, a peasant woman named Vuissane Testanière recalled how two of her neighbours sat chatting in the sun as their daughters deloused them.

Medieval people also had to deal with some less familiar creatures: because parasites were a product of corruption, they could occur in some unexpected parts of the body. Toothache was widely believed to be caused by ‘toothworms’, which lived in dental cavities and had to be smoked out of the body using burning henbane or camomile seeds.

Today we use the term ‘earworm’ for catchy tunes, but in earlier centuries earworms were thought to be creatures that caused an itching, tingling sensation, and were treated using the same bitter liquids as intestinal worms. Alternatively, the physician Gilbert the Englishman (c. 1180–1250) suggested leaving a warm, ripe apple next to the ear overnight. In the morning, the worm should be found in the middle of the fruit.

Although the sheer number of surviving recipes for treating parasites suggests that they were a serious problem for medieval people, it also indicates that – for the most part – people were unwilling hosts to these unpleasant guests.

How lice signalled holy humility

One possible exception to this rule was the clergy. Holy men and women were thought to be prone to parasites due to their lack of grooming and their frequent consumption of phlegmatic foods, especially fish. In the 13th century, the German prior and author Caesarius of Heisterbach (c. 1180–1240) worried that the vermin and lice that commonly infested the brethren’s robes would serve as a deterrent to would-be monks.

But the association between parasites and piety could also be seen as a positive thing. During the canonisation process for Thomas de Cantilupe, Bishop of Hereford (c. 1218–82), his servants testified about the vast quantities of lice that had covered his clothing, sometimes as many as a man could hold in his hand. This was seen as a positive thing, demonstrating his humility and asceticism.

One 15th-century holy woman, Catherine of Genoa (1447–1510), went even further. Filled with disgust at the lice that infested the sick women to whom she ministered, she was instructed by ‘the Spirit’ to eat a handful of them, and thus overcame her repugnance.

That such behaviour could be thought saintly suggests that most people considered heavy infestation with parasites to be both unusual and disgusting. During the Third Crusade (1189–92), according to the Norman poet Ambroise, the only women who were permitted to travel with the army were “the good old charwomen… who washed heads and linen and were deft as monkeys in removing fleas”.

When Thomas de Cantilupe’s old clothes were given away to paupers, they had to be deloused – even those poor enough to need charity would be reluctant to accept such dirty garments. And in later 15th-century Mantua, prisoners complained that they were “dying of hunger… [and] beset with bedbugs, fleas and lice”.

That even marginal members of medieval society were disturbed by potential contact with parasites surely shows that, while medical ideas about parasites may have changed over the centuries, human reactions to them have not.

In our very visceral reactions to nits, lice and worms, we have rather more in common with our distant ancestors than we might think.

About the author

Katherine Harvey

Dr Katherine Harvey is a medieval historian based at Birkbeck, University of London. She is the author of ‘The Fires of Lust: Sex in the Middle Ages’ (Reaktion, 2021), a Sunday Times Paperback of the Week. Her writing has appeared in publications including BBC History Magazine, History Today, The Sunday Times, The Times Literary Supplement, and The Atlantic.