Texts that are hundreds of years old might yield clues to medical problems of the past. But without a body, a definitive diagnosis is rarely possible. And unless you know the context of what you’re reading, it’s possible to go very wrong with retrospective diagnosis.

I’m a historian of medieval and early modern medicine, and when I tell people what I do for a living, the main question I get asked is, ‘So did you find out what was wrong?’ People often imagine me as some sort of historical pathologist looking for a modern diagnosis.

It’s natural to seek an empirical truth, an understandable explanation for a problem, and historians are also under pressure to link their work to the present day to demonstrate that what they do is relevant. But, tempting as it might be, there are lots of dangers in medical historians using modern diagnostic categories.

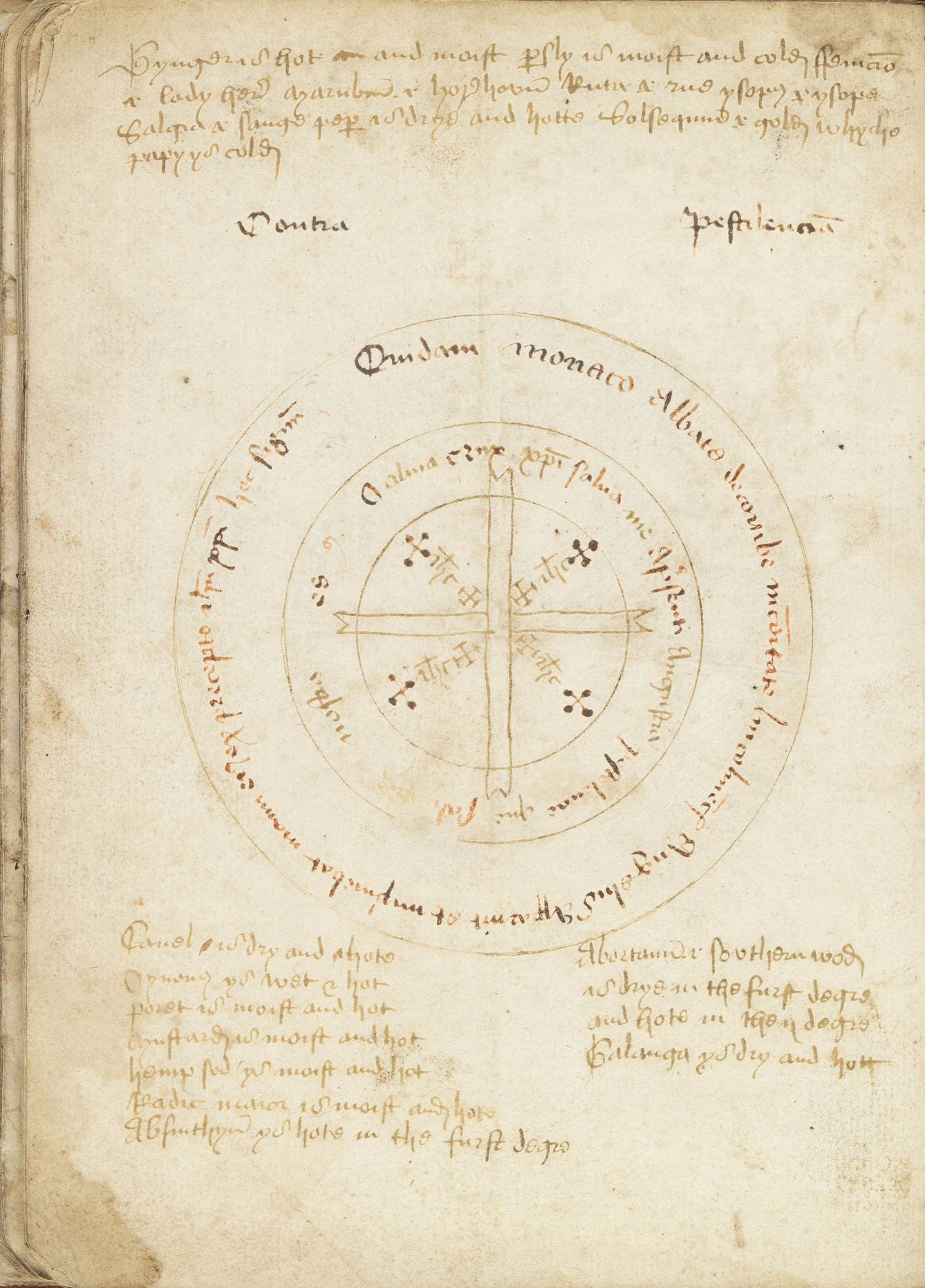

We now know that Yersinia pestis caused plague, but in the 15th century people believed in more metaphysical causes, as illustrated by this talisman against plague.

The bare bones of diagnosis

Sometimes pathogens can be identified in past populations through the analysis of skeletal remains. Debates around the causes of the Black Death, which reduced the population of Europe by at least a third in the mid-14th century, went back and forth between academics from all backgrounds up until the end of the 20th century.

Some argued for the bacterium Yersinia pestis – bubonic plague – others for something else. But with DNA evidence from plague pits and collaboration between scientists and historians, we now know that a primitive strain of Yersinia pestis was in fact the culprit – or at least, one of the culprits.

In the majority of cases, however, we can’t use bones to give us answers, because most diseases don’t affect skeletal remains.

Alfred the Great might have suffered through terrible bowel problems… or his experiences may have been exaggerated by admirers who felt he deserved a sainthood.

King Alfred’s complaint

I don’t want to make this purely about monarchs and other famous figures, but unfortunately those are the individuals whose lives we know the most about, so they are prime targets for retrospective diagnosis.

Let’s begin, then, with a well-known figure from Anglo-Saxon England: Alfred the Great, King of Wessex (871–99). In 1991, nurse Gillian Craig published an article giving Alfred a definitive diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, a modern autoimmune condition that causes the intestines to inflame. The most common symptoms include pain, bloating, diarrhoea, anal fistulas and lethargy. Occasionally, people with Crohn’s experience constipation.

We don’t have Alfred’s bodily remains, and even if we did, his skeleton would tell us nothing about any soft-tissue problem. Craig’s claim is based purely on written sources. Asser’s ‘Life of Alfred’ was written by a man who was intimately acquainted with Alfred. Asser tells us that after Alfred’s marriage to Ealhswith in 868, he:

was struck without warning in the presence of the entire gathering by a sudden severe pain that was quite unknown to all physicians. Certainly it was not known to any of those who were present on that occasion, nor to those up to the present day who have enquired how such an illness could arise and – worse of all, alas! – could continue so many years without remission, from his twentieth year up to his fortieth and beyond. Many alleged that it happened through the spells and witchcraft of the people around him; others, through the ill-will of the devil, who is always envious of good men; others thought that it was the result of some unfamiliar type of fever; still others thought that it was due to the piles, because he had suffered this particular kind of agonising irritation even from his youth.

So Asser reveals that Alfred suffered pain (although not where he had this pain), and that some people thought it was caused by a fever and others by piles (ficus in Latin).

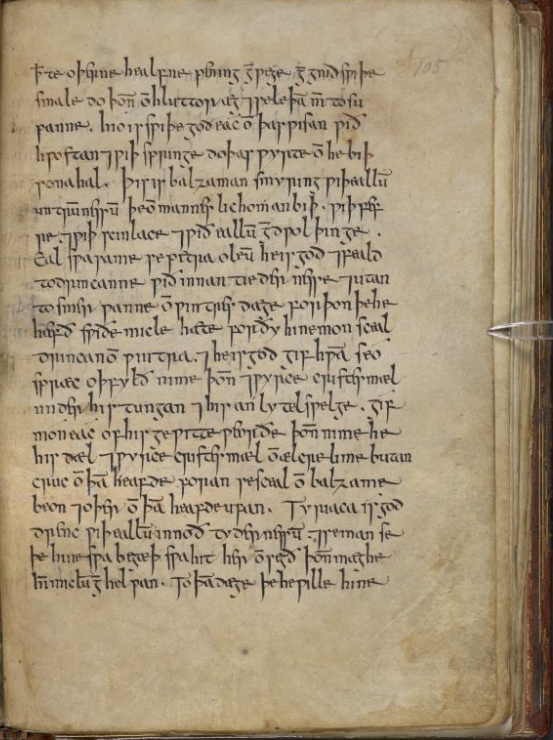

Bald’s ‘Leechbook’ tells us that Alfred the Great was sent remedies for constipation, diarrhoea and pain in the spleen all the way from Jerusalem.

The saintliness of suffering

The other piece of evidence for Alfred’s ‘condition’ is Bald’s ‘Leechbook’, a medical compendium assembled in Alfred’s reign. The ‘Leechbook’ states that Elias, Patriarch of Jerusalem, sent Alfred some remedies for constipation, diarrhoea and pain in the spleen. Diarrhoea and constipation are such universally common conditions that it isn’t particularly surprising that he would be sent remedies for them.

This, then, is the sum total of the evidence that we have for Alfred’s illness. Bald’s evidence is brief, and we must keep in mind that Asser’s ‘Life’ is written in a hagiographical form – that is, a text designed to emphasise the sanctity of the subject. One of the things these sorts of texts do is stress extreme suffering as a marker of saintly worth. So, despite the fact that Asser knew Alfred personally, he might well have exaggerated just how awful Alfred felt.

Fungus or witchcraft?

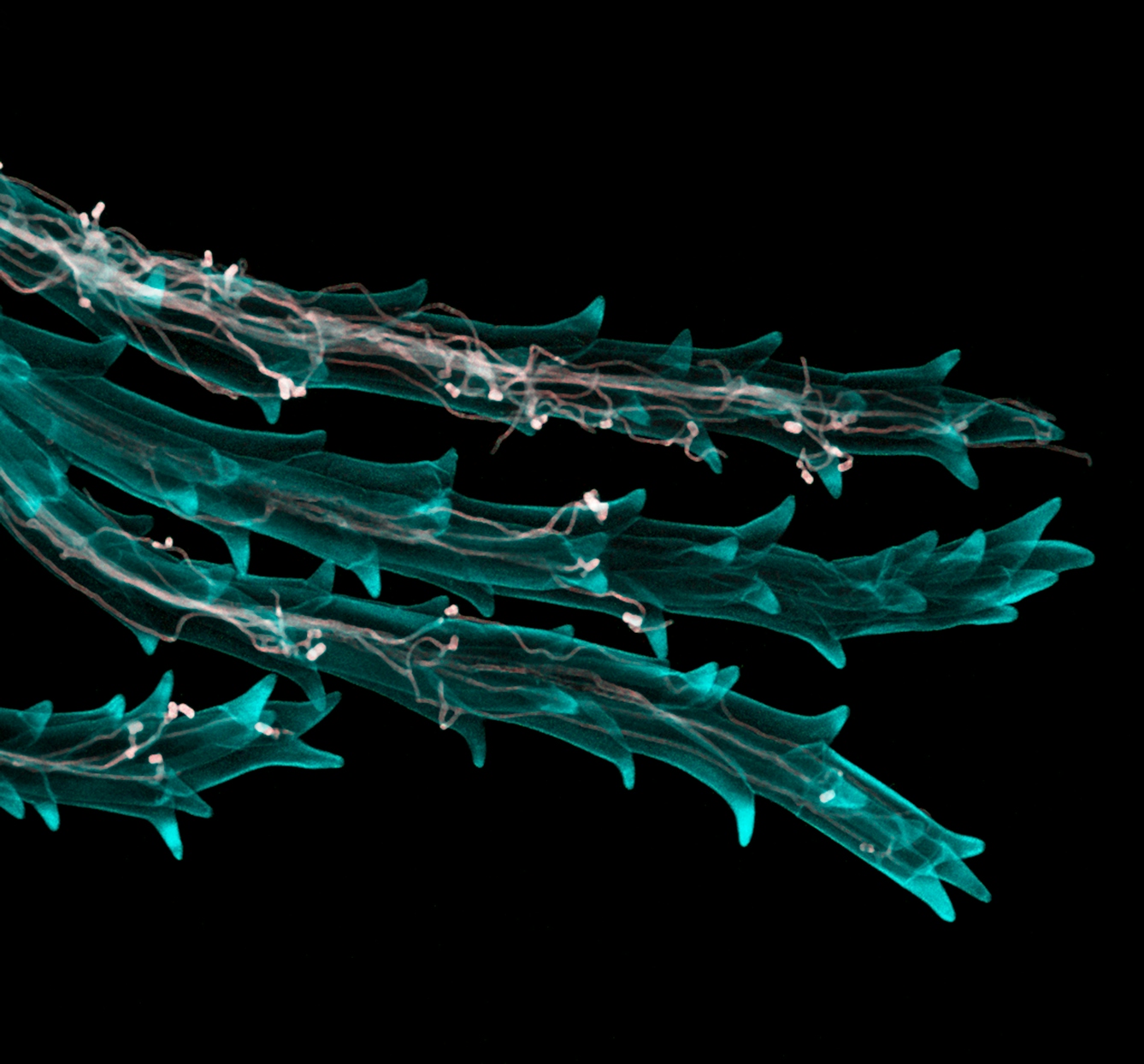

Retrospectively diagnosing modern medical conditions in past populations is also a way to try and understand mindsets that are alien to us. To steer away from the royals, let’s take a diagnosis that’s been applied to a group of people. Ergotism is a condition caused by the long-term ingestion of a fungus called ergot that grows on grains of rye. Ergot contains a toxin with properties similar to those of LSD, and therefore causes mental symptoms such as psychosis and mania, as well as gastric upset and convulsions.

In pictures

Linnda Caporael has posited ergotism as the cause of the sickness that triggered the Salem witch trials.

There are many other aspects of society that led to the witch trials and deaths of women such as Sarah Good, and these are potentially far more fruitful (and interesting) for historians to uncover rather than guessing at a medical diagnosis that can never be confirmed.

In the 1970s, Linnda Caporael, a behavioural psychologist, was studying the Salem witch trials of 1692. Witchcraft was blamed when several children in Salem became very unwell. Reported symptoms included abnormal speech, strange postures and gestures, and convulsions. Based on an examination of these symptoms, the weather conditions that year, which allowed the fungus to grow, and Salem’s physical environment (which was also favourable to ergot), Caporael published an article in 1976 suggesting that ergotism was the cause of the sickness.

It is undoubtedly a good thing to want to exonerate women falsely accused of a crime they almost certainly did not commit nearly 400 years ago. And Caporael does acknowledge the problem with alien mindsets:

The utmost caution is necessary in assessing the physical and mental states of people dead for hundreds of years. Only the sketchiest accounts of their lives remain in public records. In the case of ergot, a substance that affects mental as well as physical states, recognition of the social atmosphere of Salem in early spring 1692 is basic to understanding the directions the crisis took. The Puritans’ belief in witchcraft was a totally accepted part of their religious tenets. The malicious workings of Satan and his cohorts were just as real to the early colonists as their belief in God.

Suggesting a modern medical condition as a cause flattens out a fascinating snapshot of life in early America. It’s much more interesting, in my opinion, to examine the cultural and social context in which these accusations arose to get a fuller picture.

Pieter van Foreest was a physician in the 16th century. He believed that gonorrhoea could be passed on through sex or caused by injury or celibacy.

Groin strain and gonorrhoea

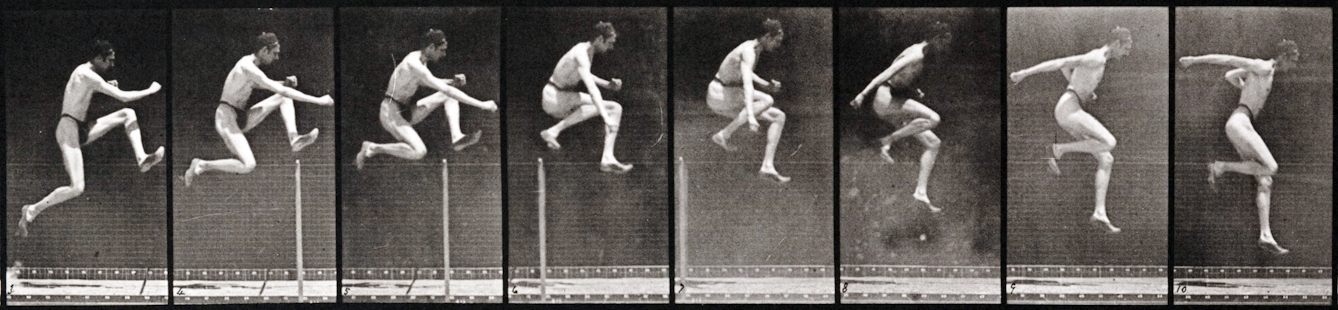

Another problem in diagnosing the past is one of terminology. Let’s take ‘gonorrhoea’, a common diagnosis in early modern records. An interesting example is that of Robert Higgens, who consulted the astrologer and medical practitioner Richard Napier in January 1604. Higgens sprained his groin by leaping over a hedge, and this caused ‘gonorrhoea’.

Can gonorrhoea be caused by jumping?

Of course, today the word ‘gonorrhoea’ refers to a specific sexually transmitted disease caused by the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae. But in the 17th century gonorrhoea – from the Greek gonos (semen) and rhoia (flux) – meant a discharge from the genitals. According to the physician Pieter van Foreest (1521–97), gonorrhoea had three causes: sexual transmission, trauma to the genital area, and celibacy (thanks to Boyd Brogan for sharing his translation of van Foreest's work). So based on this definition, Napier’s diagnosis makes perfect sense.

Historians trying to trace a history of Neisseria gonorrhoeae through written documents are likely to be misled, especially since one cause of this condition in the early modern period was celibacy – the very opposite of how the gonorrhoea we know today is spread.

The madness of King George?

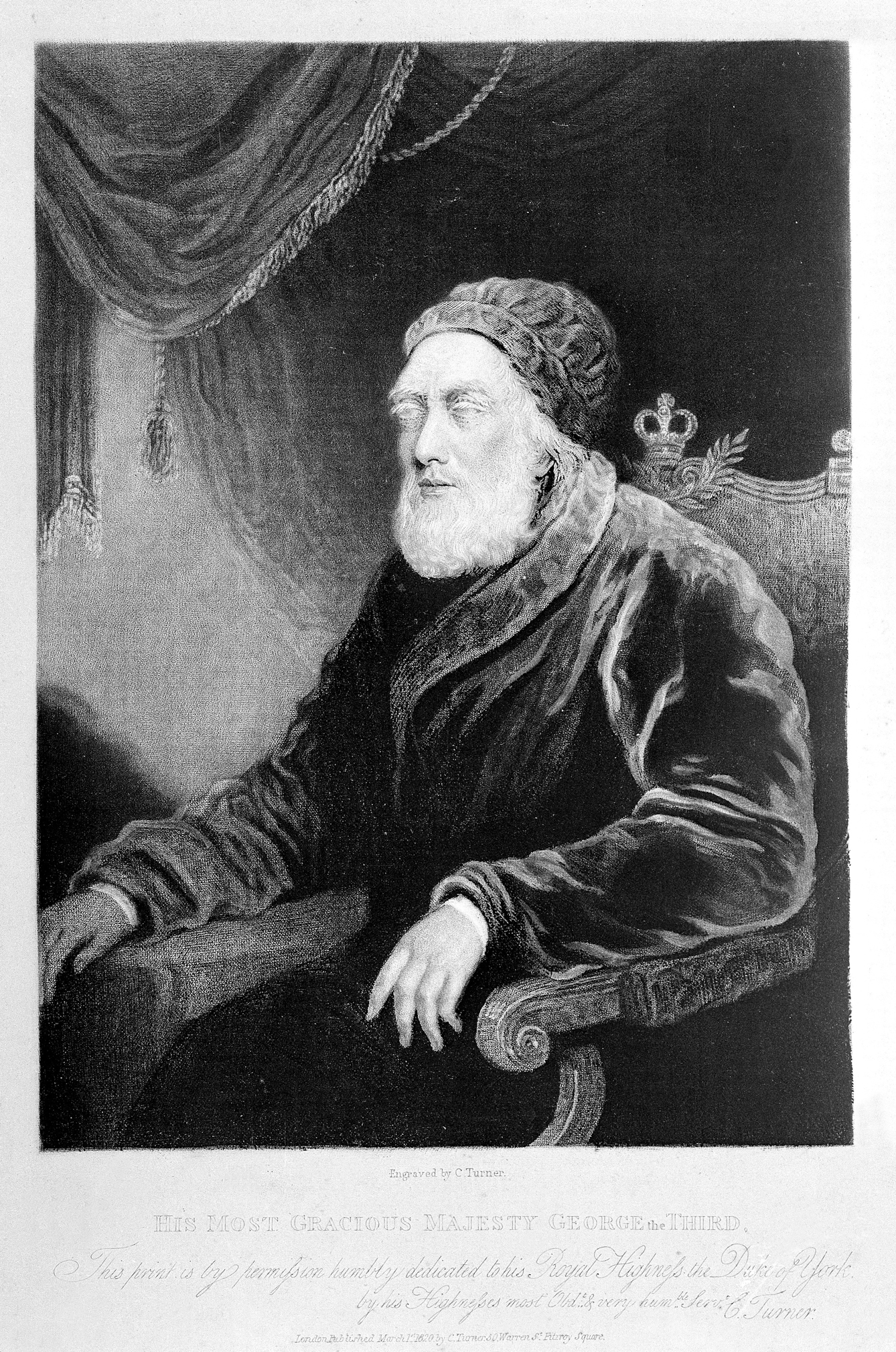

A final important issue with retrospective diagnosis is that it can be used as a political tool, as in the example of George III (1738–1820). Alan Bennett’s play ‘The Madness of George III’ and the film adaptation ‘The Madness of King George’ suggest that George was not ‘mad’, but was suffering from a condition called porphyria, a neurological disorder of which periods of confusion are one symptom.

The diagnostic team behind this claim were a mother-son psychiatric duo, Richard Hunter and Ida Macalpine, whose book ‘King George and the Mad-Business’ (1969) was hugely popular. The authors combed the voluminous records produced by George’s physicians during his several periods of incapacity, and picked the symptoms that suited their conclusion.

King George III's diagnosis is impossible to know – and less interesting than the rumours and fighting for power triggered by his absence from governing.

Even from a modern perspective, this diagnosis does not stand up, as pointed out in several articles by Timothy Peters (a physician who, unfortunately, goes on to give us his own questionable retrospective diagnosis that George’s problem was bipolar disorder). Acute porphyrias usually have a genetic basis, so we would expect to hear reports of similar symptoms in both George’s ancestors and descendants. But such evidence does not exist.

So why was the diagnosis of porphyria so readily accepted? Simply put, the idea that the royal family might be ‘tainted’ with mental illness was not savoury, and the porphyria diagnosis was a way to show that George’s problem had a physical, ‘unpreventable’ cause.

The sad truth is we will probably never shake the porphyria myth. Whatever afflicted George, he was severely impaired over long periods. Working out ‘exactly what was wrong’ says nothing about his life – or his suffering.

Stories about symptoms and society

Retrospective diagnosis is by no means a done debate among historians of medicine – many colleagues who I respect a great deal will disagree with my position. I may even change my mind in future.

But for now, I don’t see it as my job to impose modern categories of thinking onto past cultures. My role is to discover how medical practitioners and patients in the past thought about their illnesses – how they diagnosed sickness, what their treatments were, and how they described their diseases – in order to better understand the worlds they inhabited.

About the contributors

Joanne Edge

Dr Joanne Edge is a historian who specialises in late-medieval and early modern European social and cultural history, with an emphasis on medicine and the ‘occult’ sciences: divination, magic and astrology. She has previously worked as Assistant Editor on the Wellcome-funded Casebooks Project at the University of Cambridge and is currently Latin Manuscripts Cataloguer at the John Rylands Library, University of Manchester. Her first book, ‘Numerological Divination in Late Medieval England’, is under contract with Boydell and Brewer.