The choices a curator makes – what goes in? what stays out? why? – are often as fascinating as the exhibition itself.

Inside the mind of Ayurvedic Man’s curator, Bárbara Rodriguez Muñoz

Words by Gwendolyn Smith

- Interview

Steel forceps that resemble the long, sharp beak of a heron. A blunt pair of tongs moulded to look like a lion. These animal-shaped surgical tools aren’t just a star exhibit in the ‘Ayurvedic Man: Encounters with Indian Medicine' show. They also, according to curator Bárbara Rodriguez Muñoz, sum up one of its key messages.

As replicas of ancient Ayurvedic instruments produced during the British Raj in India, they distil how medical heritage is a multi-layered, endlessly evolving beast. “I love the idea that in the 20th century an ancient tool that looks like a heron or a tiger would be reimagined – and what this says about the cross-fertilisation of knowledge between the East and the West,” she says.

“I love the idea that in the 20th century an ancient tool that looks like a heron or a tiger would be reimagined – and what this says about the cross-fertilisation of knowledge between the East and the West.”

The exhibition explored the exchange of wisdom between Indian Ayurvedic traditions and Western biomedicine through a series of letters between two men. The first is Paira Mall, a young Indian doctor who – at the start of the 20th century – was paid £500 a year by drugs philanthropist Henry Wellcome to travel around his native country on the hunt for medical paraphernalia. The second? C J S Thompson, the head curator of Wellcome’s library.

Sifting through the letters yielded a revelation for Rodriguez Muñoz: Mall was an agent of medical knowledge as well as a collector. “He was as interested in botanical plants and how they were used by indigenous populations as he was in the objects for the museum,” she says. “Some of them were taken to Wellcome’s pharmaceutical laboratories to be turned into products that could be for sale in the West.”

Dr Paira Mall’s correspondence with Henry Wellcome formed the backbone of the exhibition.

The colonial question

Focusing on objects such as the story-imbued animal tools was part of a plan to highlight “artworks that presented a great deal of cultural layering”. Or, in other words, those that demonstrate how medical traditions have been shaped by people from all corners of the globe.

But when Rodriguez Muñoz was originally briefed to produce a showcase of Indian medicine, she didn’t imagine this was the form the show would take. It was only after meeting scientists, artists and Ayurveda scholars during a research trip to India that she narrowed down the focus. “I realised that all their diverse perspectives and narratives wouldn’t fit within the gallery walls. We felt that by focusing on our collection we could approach what is a wide and complex topic with more integrity.”

Indeed, taking this approach offered an opportunity to confront the problematic context of the exhibition. After all, as Rodriguez Muñoz puts it, Ayurvedic Man involved “a Western institution with a Western curator and a collection amassed by a Western businessman engaging with Indian medicine”. So, how did they deal with it?

First and foremost, it came down to transparency. “We’re not just saying what the objects are. We’re saying who collected them – and why they were collected,” says Rodriguez Muñoz. Including the word ‘encounter’ in the show’s title was also significant, she explains. “We use it to talk about the exchange of information, a collaboration – but also to talk about exploitation and conflict.”

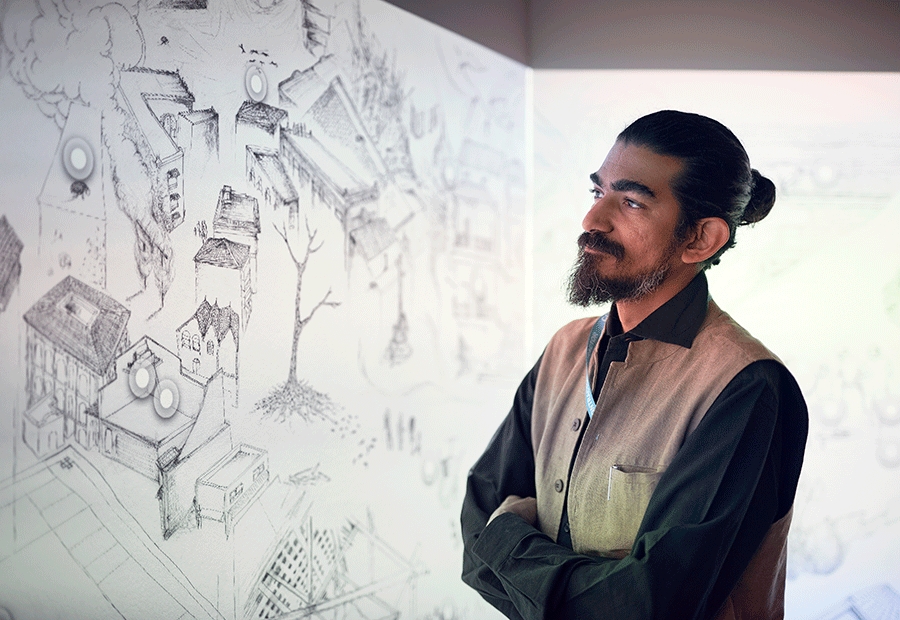

Paying attention to who was shaping the exhibition narrative was also key. Mumbai-based artist Ranjit Kandalgaonkar responded to the somewhat knotty premise in Drawing the Bombay Plague, one of the original artworks commissioned for the show.

Meanwhile, curatorial adviser Sita Reddy has a special interest in decolonising collections. “She has really pushed us critically and intellectually in terms of the framing and interpretation for the exhibition. I had an early intuition to zoom into the material culture and to forget more grandiose narratives, and she pushed me in this direction,” says Rodriguez Muñoz.

Acknowledging this troublesome foundation lent the show a dual focus. It was not only about enthralling objects; it also scrutinised the nature of collecting itself. This approach also set a precedent for future exhibitions. “Next time we re-curate our permanent historical collections, there are some lessons and processes learned with this show in terms of acknowledging the provenance and contexts of the collections. That’s along with bringing different voices to frame them.”

“A great deal of this medicinal knowledge is domestic, as opposed to codified or professionalised, and has been used by women for generations.”

Women and medicinal knowledge

There was one additional thorny element to wrangle with: the lack of women’s voices in medical history collections. “The anatomical maps in our collections, such as The Ayurvedic Man(view in catalogue), are mostly based on male anatomy, unless it deals with pregnancy or birth. Even erotic manuals were primarily directed at the male ruling classes,” says Rodriguez Muñoz.

A section in the exhibition was dedicated to acknowledging this void – along with the patently gendered title of the show. One of the jewels was a beguiling Kalighat painting depicting a woman and, well, some aubergines. If this sounds prosaic, that’s because – on one level, at least – it is. Rodriguez Muñoz says she chose to include the image because “aubergines are used in Indian kitchens to treat conditions such as inflammation, fever and general weakness”.

Yet there’s a more profound message to be gleaned, too. “I wanted to stress how a great deal of this medicinal knowledge is domestic, as opposed to codified or professionalised, and has been used by women for generations,” she explains.

Aside from the rich symbolism of aubergines, what might you have missed if you didn’t look closely? The material is “extremely detailed, delicate and beautiful”, says Rodriguez Muñoz. “We display Tibetan manuscripts depicting animals and goddesses, along with South Asian anatomical maps charting emotions, blockages, chakras and metaphysical energies.”

The letters, she says, also “need some time to sink in”. Written by male academic professionals of the era, they employ imperialist expressions shot through with contempt towards other cultures. But this is revealing, the curator insists. “Through their anecdotes and wording they unpack the power structures existing at the time – and how they play out in medicine, culture and gender.”

There was plenty of time to mull over intricacies such as multilingual ancient manuscripts, or Henry Wellcome’s stern annotations on Thompson and Mall’s correspondence, because the show’s layout enabled visitors to get up close and personal with the exhibits.

Exhibition designer Andres Ros Soto devised freestanding panels so that the material could be displayed vertically, which enabled intimate engagement. He also came up with the exhibition flooring. This was inspired by traditional weaving techniques but used contemporary materials – recycled plastics – to avoid “falling into any gimmicky aesthetics”, as Rodriguez Muñoz puts it. These were offset by vibrant blue walls that reference Lapis lazuli, a gemstone revered for its healing power in certain strands of Ayurveda, along with a typography inspired by Sanskrit manuscripts and conceived by the graphic design studio HATO.

“I was impressed by his ability to turn academic research around a very controversial moment in history into such engaging visual material,” says Rodriguez Muñoz of Ranjit Kandalgaonkar.

Enlightening ideas

Amid the plethora of ancient objects on display were two provocative new commissions. One of these has already been mentioned: Ranjit Kandalgaonkar’s Drawing the Bombay Plague, which explores the eponymous 1896 epidemic. It’s an expansive and intricate drawing depicting the unpopular measures imposed by the British administration during the outbreak (sanitation, quarantine, hospitalisation), and the resulting local responses.

The accompanying interactive platform, developed with HATO, reveals Kandalgaonkar’s research in both the Wellcome Library and the Asiatic Library in Mumbai, where he drew inspiration from the satirical cartoons of Hindi Punch magazine.

Rodriguez Muñoz first came across Kandalgaonkar during her research trip to India, where she met his partner, the artist Vinita Gatne, at a café in Colaba. Kandalgaonkar had already been working on the plague and Gatne produced a folder brimming with his “detailed, raw and humorous” pencil drawings. “I was impressed by his ability to turn academic research around a very controversial moment in history into such engaging visual material,” says Rodriguez Muñoz.

When Kandalgaonkar came to London for six months to explore Wellcome’s collections, he spent the time “compulsively digging into our archives, challenging our institutional ways in the most constructive and enjoyable ways, and drawing – night after night,” says Rodriguez Muñoz. “He is very missed,” she adds.

The second original work is the film ‘Quiet Flows The Stream’, created by Calcutta-based Nilanjan Battacharja. In it, two contemporary Indian medics discuss their work: Kunjira from the south of the country and Thendup from next to Nepal in the north. A segment to look out for if you’re interested in the gender gap issue in the collection, Rodriguez Muñoz says, is when Kunjira complains that his son is not interested in his medical knowledge, but then reveals he has found another person, a girl, to pass on his knowledge to.

This small-scale evolution nods to the interminable shifting and reconfiguring that takes place in medicine in a wider context – one of the key takeaways from Ayurvedic Man.

Taking this angle wasn’t just an inevitable response to Paira Mall and Henry Wellcome’s collaboration. According to Rodriguez Muñoz, it’s also a vital message to promote in today’s political climate, where nationalism is on the rise across the world.

“These are enlightening ideas with which to fight narrow-mindedness,” she says. “With the current impulse to erode diversity, we ought to present medicine and healing as something fluid that has been shaped across millennia by different cultures, as opposed to belonging to just one community.”