The first flushes of love, especially when it’s unrequited, can produce uncomfortable and disconcerting feelings – almost like an illness. While we may no longer consider lovesickness a disease today, it was long considered a genuine affliction.

A short history of lovesickness

Words by Aisha Mazhar

- In pictures

An erratic heartbeat, sickly pallor, loss of appetite and general feelings of dejectedness were considered the telltale symptoms of lovesickness. Modern science now recognises that when in love, our brain transmits various hormones that can cause intense physical and psychological symptoms, which aren’t always pleasant. Perhaps there is some truth in the description ‘lovesick’ after all.

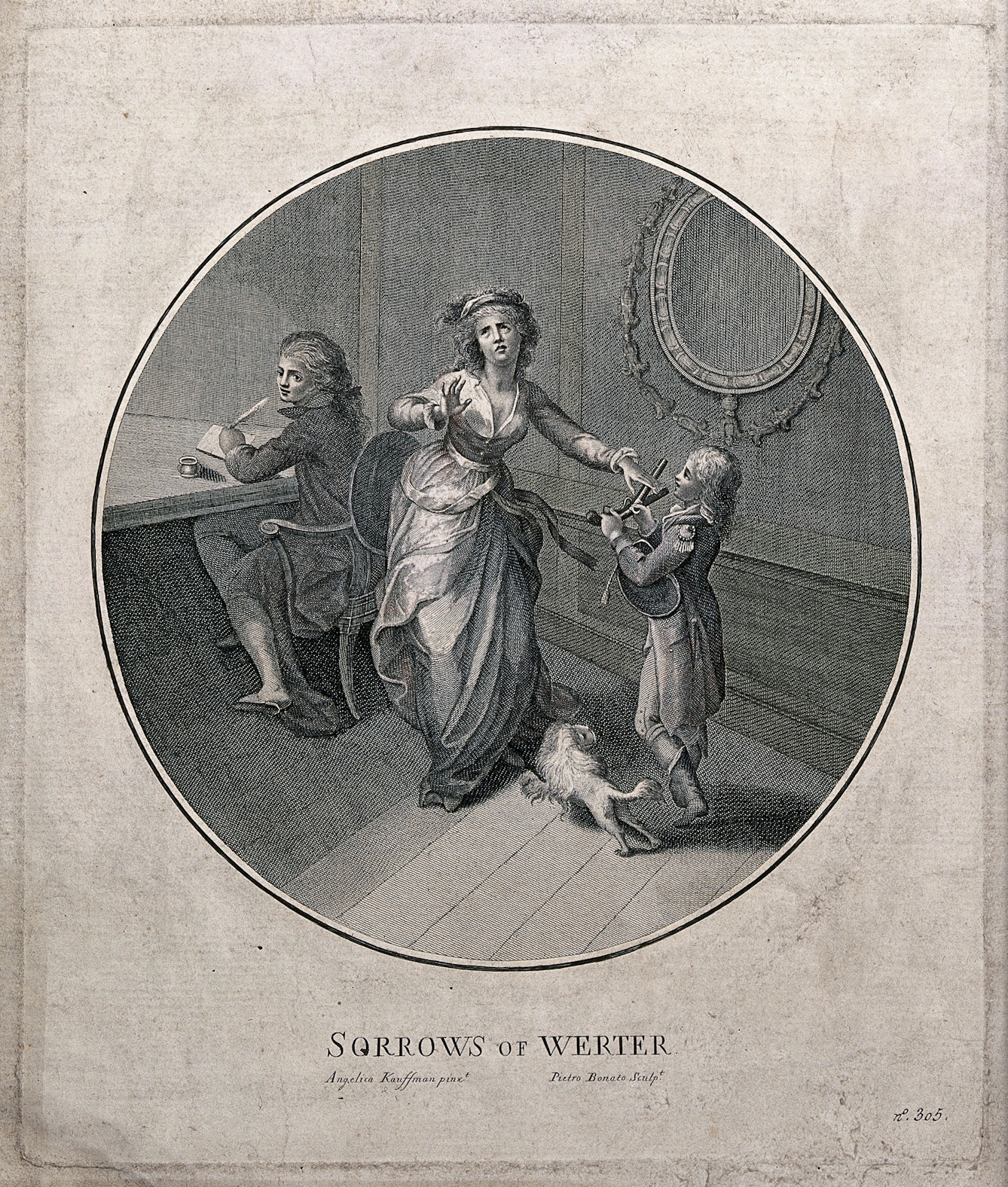

Writers and artists have long depicted love as a malady that can drive people to madness. Shakespeare described how “lovers and madmen have such seething brains”, and in Goethe’s ‘The Sorrows of Young Werther’, the sensitive protagonist’s infatuation with the already betrothed Charlotte drives him to despair and proves fatal. Those whose love was unfulfilled or unrequited were considered particularly susceptible to lovesickness.

The best way to diagnose lovesickness was to take the patient’s pulse, according to Greek physician Erasistratus. He was called to the bedside of Prince Antiochus, who was suffering from a mysterious ailment. Antiochus’s pulse would quicken in his stepmother Stratonice’s presence: Erasistratus realised he was lovesick. To cure his son, Antiochus’s father sacrificed his marriage to allow Antiochus to marry Stratonice.

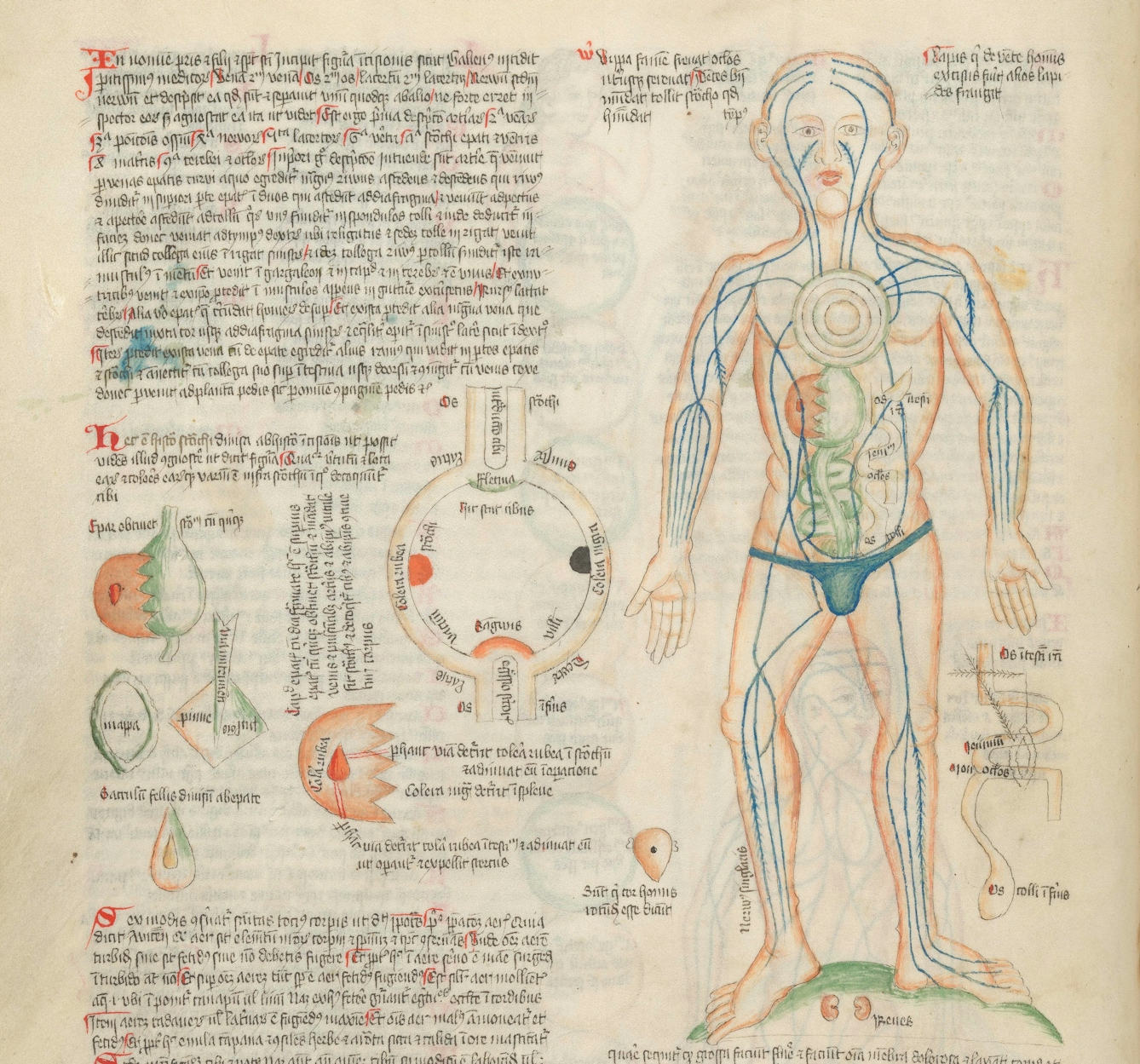

Medieval physicians believed lovesickness was caused by the production of excess black bile in the body. According to humoral medicine, emotional disturbances such as melancholy, which was closely related to lovesickness, were caused by an imbalance of humours. The body could be purged of excessive bile through laxatives and bloodletting to rebalance the humours.

Not all sufferers of lovesickness were considered alike. In the Middle Ages, lovesickness was regarded as a class-specific male malady, associated with the intellect. The sufferers were often noblemen. During the Renaissance, the lovesick female figure became more prominent, but female lovesickness was seen as a disorder of the womb.

A lovesick nobleman in the Middle Ages could expect to be prescribed baths, sports and even “therapeutic intercourse” as a way of distracting them from thoughts of their beloved, whereas a lovesick woman was exempt from such sexual liberty and prescribed marriage instead.

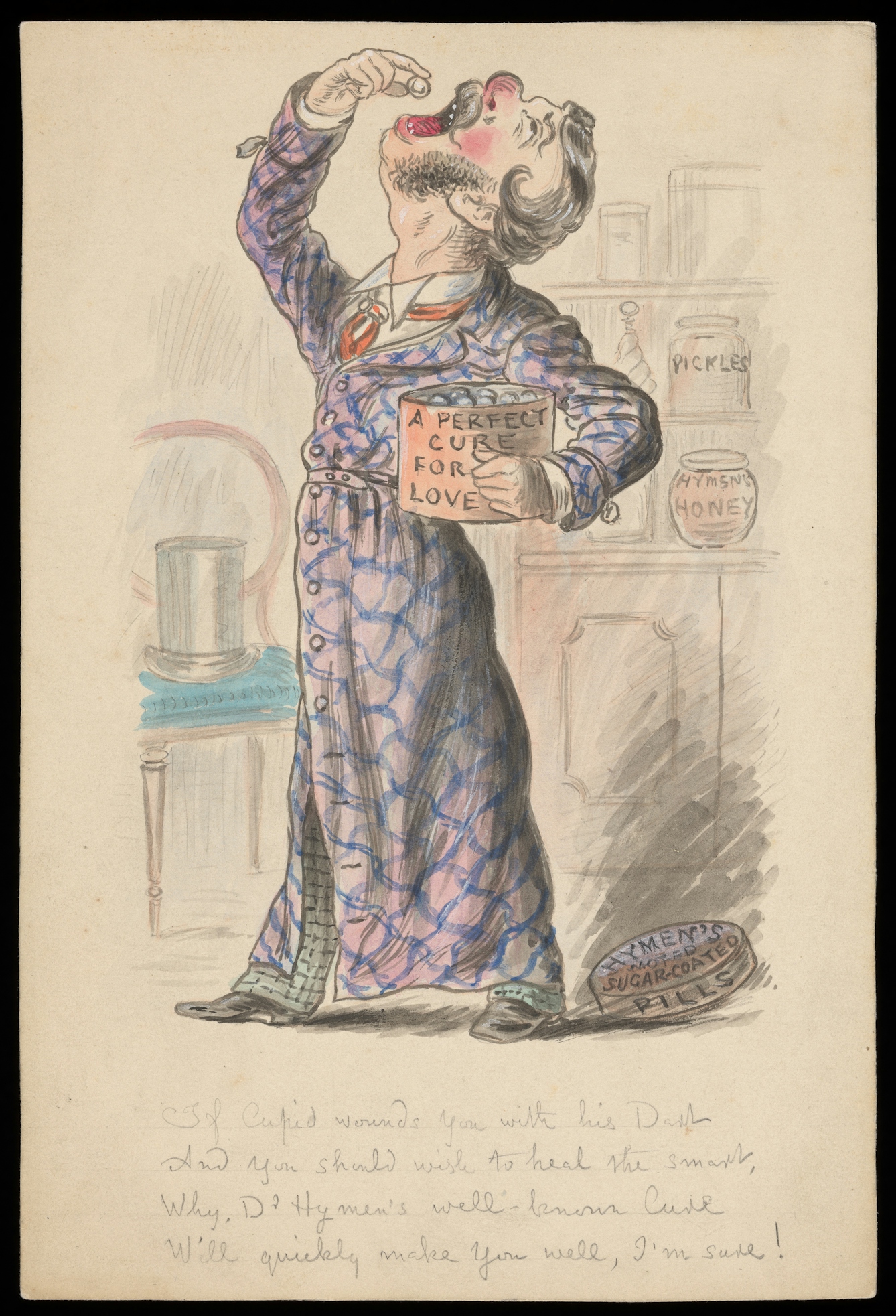

For anyone in the throes of lovesickness in the 17th century, Robert Burton’s ‘The Anatomy of Melancholy’ (1628) and Jacques Ferrand’s ‘A Treatise on Lovesickness’ (1610) were the books to turn to. They examined the causes of “love melancholy” and offered a variety of novel cures and preventative measures. Ferrand suggested an enema, plus warm air for men and cold air for women. He also advised women to avoid wearing clothes lined with ermine skins and velvet, as it could heat their blood.

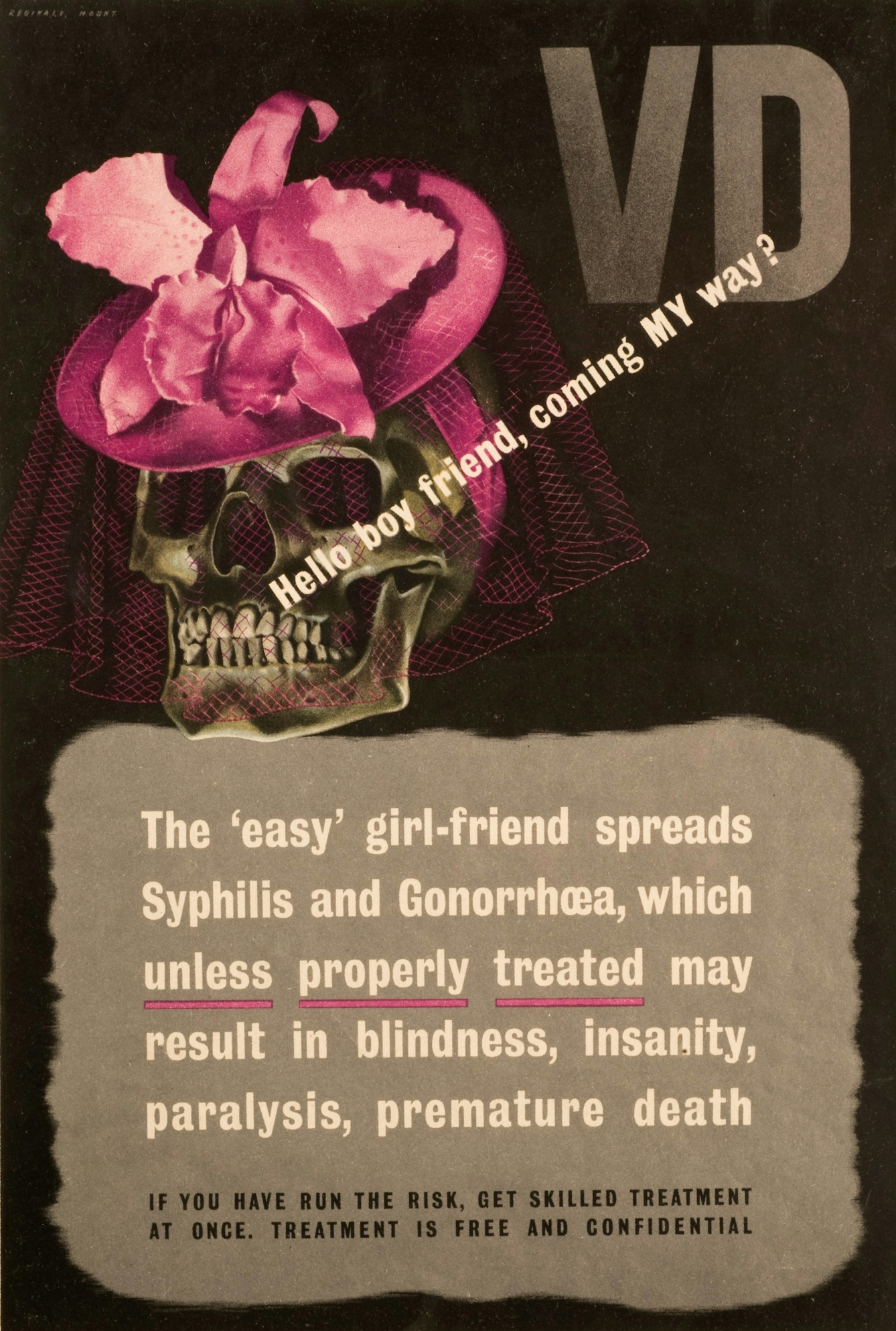

Later, when lovesickness was not considered a medical condition, people recognised other ways that love could prove to be fatal: via sexually transmitted diseases. Posters would issue stark warnings about the complications syphilis can cause, including this one from the 1940s, which warns of blindness, paralysis and death. According to historian Jacalyn Duffin, “The recognition of syphilis as a mortal peril enhanced medical interest in the problem of affectionate love.”

Later in the 20th century the dangers of love were reframed with the advent of HIV/AIDS. Unlike syphilis posters, which often emphasised the consequences, AIDS posters stressed preventative measures. This poster from 1988 reads “…the lovesick that comes with AIDS doesn’t go away”. Posters like this one, featuring heterosexual couples, focused on the love side of sex, with condoms presented as an act of care. In contrast, posters with lesbian and gay couples were more sexually explicit and suggestive of casual sex without love.

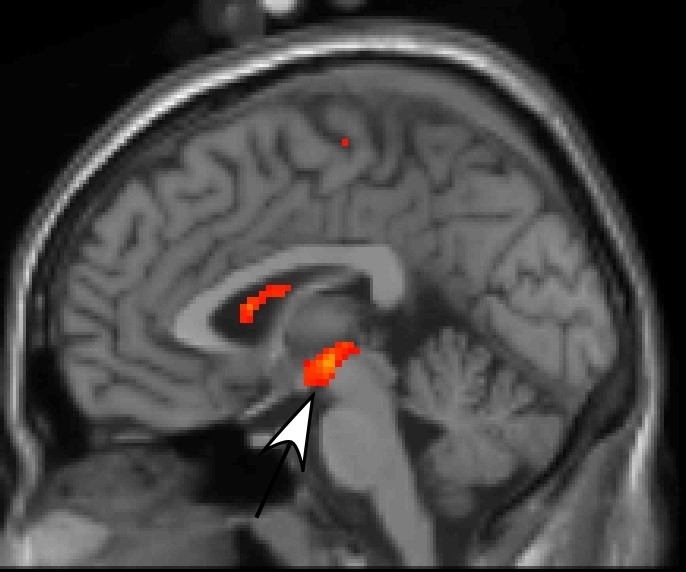

More recently, scientists have revisited the possibility that lovesickness might produce real symptoms. When we are heartbroken, our brain reacts in a way comparable to drug addicts experiencing withdrawal, illustrating how powerful love can be. The physical and emotional symptoms of both love and heartache, as we experience them today, are remarkably consistent with historical descriptions of lovesickness. Next time you’re feeling a little lovesick, perhaps you may find solace in thinking of the countless people who have endured similar feelings through time.

About the author

Aisha Mazhar

Aisha is on the Wellcome Trust Graduate scheme. Prior to joining Wellcome, she studied History at King’s College London and co-hosted a radio show for the university’s own radio station.