How a young Indian monk's travels around the world inspired modern yoga.

Vivekananda’s journey

Words by Lalita Kaplishaverage reading time 9 minutes

- Serial

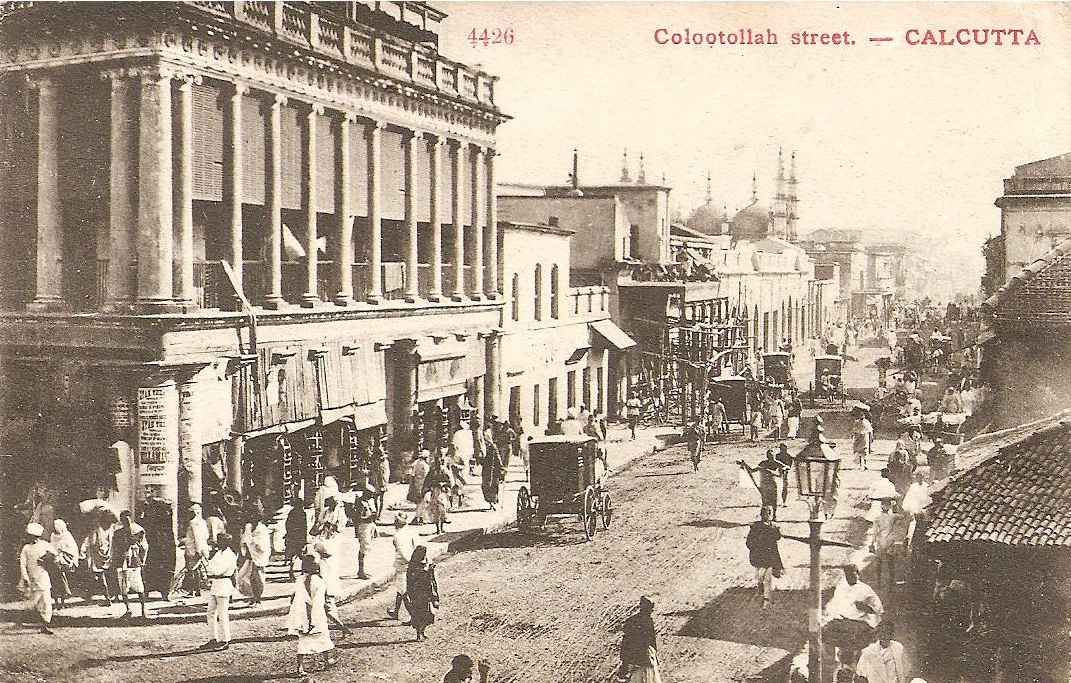

Calcutta, 1882

At the end of the 19th century Calcutta (now called Kolkota), in Bengal, was a bustling international port of call for trade and visitors from around the world. It was home not only to Bengalis but to a long-established British colonial community.

A 19th-century view of central Calcutta.

As the centre of British rule in India, Calcutta was awash with Western ideas and influences, causing many Bengalis to reassess every aspect of their lives and heritage. The result was a remarkable flourishing of Bengali literature, arts and social reform.

A map of South Asia showing areas of British Rule in pink, Calcutta is on the north-east coast, at the top of the Bay of Bengal.

In the midst of the ‘Bengali Renaissance’ a devout young man in search of answers about his identity began a spiritual journey that would result in historians describing him as “the creator of fully fledged modern yoga”.

Narendranath Datta was born to a professional middle-class Hindu family. Educated in a mix of English and Bengali traditions, he spoke both languages fluently and could read and write the ancient Indian language of Sanskrit. He also had a personal interest in Western philosophical and esoteric ideas.

As a law student in his twenties, Narendra joined the Brahmo Samaj, a religious reform movement that sought to modernise Hinduism. The Brahmo Samaj had connections with Christian reform movements such as the American Unitarian Church – one of the influx of missionary and social movements that arrived in India with colonisation.

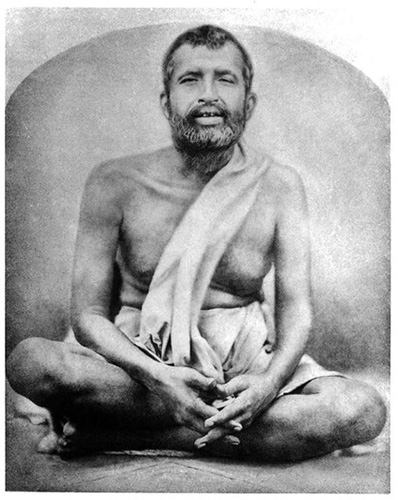

The reformer and ascetic Ramakrishna Parahamsa, 1885.

Through the leader of his Brahmo Samaj group, Keshab Chandra Sen, Narendranath met another reformer, Ramakrishna Paramhamsa, who was to change his life.

Baranagar, 1886

Ramakrishna was an unconventional Hindu ascetic who practised kundalini yoga, but also explored Christian and Sufi teachings. According to Dermot Killingley, one of the things that appealed to Narendra about him was that he taught “harmony not only of all the doctrinal traditions of India but of all religions”. In January 1886, Narendranath gave up his law studies and went to join Ramakrishna as a disciple.

A modern view of the River Hooghly at Baranagar with the Vivekananda Bridge in the distance.

Shortly after Ramakrishna’s death in 1886, Narendra took a vow of renunciation, and became a sannyasin (Hindu ascetic) taking the monastic name Vivekananda. Along with Ramakrishna's other disciples, he formed a community of monks and established a small monastery on the banks of the River Hooghly near Baranagar.

The monks at Baranagar in 1887. Vivekananda stands third from the left, wearing a turban.

Along with a life of meditation and prayer, the monks began to travel across India, preaching and visiting other religious sites and ascetics. But after five years of wanderings, Vivekananda became frustrated with the life of an ascetic.

Perhaps influenced by the zeal for social reform he encountered in Calcutta, he wanted to help the poor not just spiritually, but through social welfare. “We are so many sannyasins wandering about teaching the people metaphysics – it is all madness…” he complained. “We have to give back to the nation its lost individuality and raise the masses.”

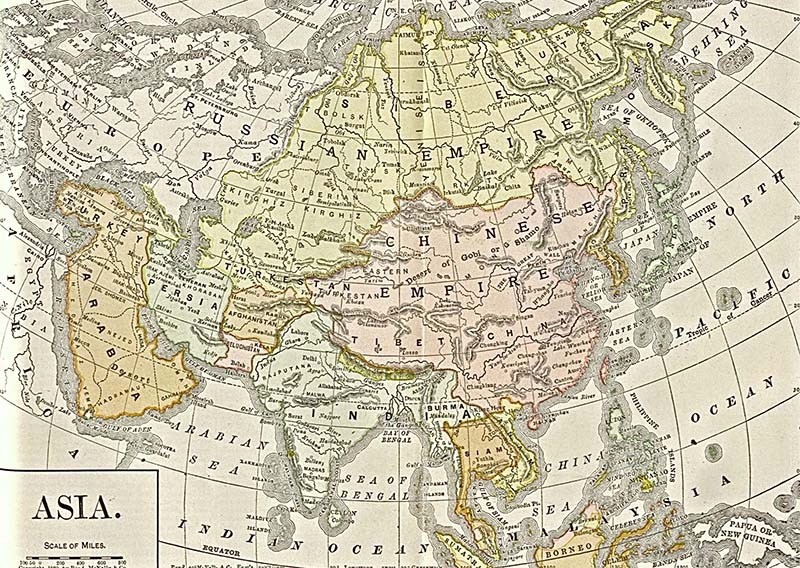

A map of Asia in 1892.

Setting sail, May 1893

The transmission of ideas across the British Empire wasn’t all one way. By the end of the century, there was increasing interest in Eastern spiritual ideas in the West.

Vivekananda must have been aware of this when he resolved to travel to America in order to raise funds for his new social project: “As our country is poor in social virtues, so this country is lacking spirituality. I give them spirituality and they give me money,” he reasoned.

In May 1893 he boarded a steamship at the east-coast port of Bombay, bound for North America. But instead of travelling West, he travelled East – first to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), then via Singapore to Hong Kong and China and finally to Japan.

Along the way, he discovered Sanskrit manuscripts at Buddhist temples in China and Japan and was struck by the influence of Buddhist and Hindu spirituality across Asia. Perhaps these encounters confirmed his belief in the international appeal of Indian spirituality.

From Yokahama, he sailed across the Pacific to Vancouver and then took a train across Canada, arriving in Chicago at the end of July.

The ferris wheel at the World’s Columbian Exposition (World’s Fair) in Chicago, 1893.

Chicago, August 1893

It must have seemed as if the whole world had arrived in Chicago for the World’s Fair in 1893. The city hosted 46 nations, each with its own pavilion, and the World’s Columbian Exposition featured an amusement park for the first time.

Poster for the Chicago World’s Fair, 1893.

Vivekananda arrived In Chicago hoping to attend the Parliament of Religions, an adjunct event to the Chicago World’s Fair. The Parliament was organised by the American esoteric community, and included representatives from around the world. The two organisations invited to represent Hinduism at the Parliament – the Bramo Samaj and the Theosophical Society – were both sympathetic to esoteric, universalist ideas of spirituality.

Vivekananda applied to join the Parliament, introducing himself as a monk “of the oldest order of sannyasins”, and on this basis he was accepted.

Vivekananda (fourth from the right) at the Parliament of Religions in September 1893.

The “handsome young monk in the orange robe” was a great success. By the end of the Parliament, he was a media celebrity: The ‘Boston Evening Transcript’ reported that he was “a great favourite at the parliament... if he merely crosses the platform, he is applauded”.

He spoke several times on topics related to Hinduism, Buddhism and harmony among religions before the parliament ended on 27 September 1893. The ‘New York Herald’ noted: “Vivekananda is undoubtedly the greatest figure in the Parliament of Religions. After hearing him we feel how foolish it is to send missionaries to this learned nation.”

After the Parliament of Religions, the American esoteric community took Vivekananda under its wing, hosting him as a guest speaker around the country. He received an enthusiastic reception, attracting many followers as he went. And this led him to reassess his mission.

A promotional poster for Vivekananda's lecture tour, describing him as "The Hindoo Monk of India".

In 1894, he set up the Vedanta Society and his work for the new organisation meant that he stayed in America much longer than intended.

New York City in the 1890s.

New York, 1896

With its mass influx of migrants at the end of the 19th century, New York City was open to new thought and experimentation. Vivekananda's main esoteric and cultist following was based in and around New York City – it was there that Madame Blavatsky had founded the Theosophical Society. So it was in New York that Vivekananda settled when he grew weary of touring the country.

The notion of yoga was already familiar in the West. The Theosophical Society did much to popularise Indian spiritual ideas, including yoga, through their publications about and translations of ancient texts.

But where the Theosophists emphasised the exclusive monastic nature of yoga, Vivekananda insisted on its universal accessibility. This fitted very neatly into the self-improvement ethos of the esoteric communities he attracted.

Vivekananda did not set out to become a yoga teacher, but because of the demand for practical spiritual techniques from his followers, he began to teach yoga classes to groups of 50 or more. In July 1896, he published his seminal book ‘Raja Yoga’ as a guide to spiritual techniques.

The 1920 edition of 'Raja Yoga' by Swami Vivekananda.

Vivekananda regarded all forms of spiritual practice as yoga. His mental and spiritual practice may not be familiar to many in today's yoga classes, but ‘Raja Yoga’ impacted on modern yoga in several ways.

By including an English translation of the Yogasutras in his book, he reinforced the connection to an ancient practice. And the open-to-all, self-improvement approach became the basis of many yoga manuals to come.

Postures receive only passing mention in ‘Raja Yoga’. Indeed, Vivekananda was quite dismissive of the physical practice, complaining that the only yoga taught in Bengal was “the queer breathing exercises of hatha yoga – which is nothing but a kind of gymnastics”.

By distancing ‘Raja Yoga’ from postural practice and all the negative connotations of the 19th-century yogi, he gave it a superior spiritual status.

High Street, Oxford, 1890s.

Oxford, 1896

In May 1896, Vivekananda found himself in “a little white house, set in a beautiful garden”, having lunch with the influential scholar and Indologist Max Müller and his wife. It was a measure of his growing international reputation that, while on a lecture tour of the UK, he was invited to Oxford to meet Müller, who was an admirer of his teacher Ramakrishna.

Portrait of Max Müller, painted at the end of the 19th century.

Like many early Orientalists, Müller was a champion of the study and dissemination of ancient Indian culture. Because of its common linguistic roots in Sanskrit, he felt it had something to offer the West.

He was not so enthusiastic about contemporary Indian culture, however, believing that it had degenerated since its Vedantic origins. In 1868 he wrote that:

India has been conquered once, but India must be conquered again, and that second conquest should be a conquest by education. (...) By encouraging a study of their own ancient literature, as part of their education, a national feeling of pride and self-respect will be reawakened among those who influence the large masses of the people. A new national literature may spring up, impregnated with Western ideas, yet retaining its native spirit and character.

His views mellowed over time, but they highlight how the colonial context impacted on cultural and spiritual concerns. Vivekananda admired Müller for “creating a respect for the thoughts of the sages of ancient India”, and he certainly would have agreed with Müller on the value of ancient traditions in engendering national pride and self-respect, but as a means of gaining independence from colonial rule.

A view across the River Hooley of Belur Math, the current Ramakrishna temple and mission at Howrah, Calcutta.

Return to India, 1897

In December 1896, Vivekananda finally set off for home. He travelled via Europe, lecturing in England, France and Italy en route, before boarding a ship in Naples. He arrived in Ceylon on 15 January 1897 and, from there, his friends and supporters organised a lecture tour, ensuring a warm reception and lots of publicity about his journey to the West.

Vivekananda (seated in the centre with a staff) with Alasinga Perumal and other supporters in Madras (now Chennai) after his first tour of America, 1897.

In May 1897, four years after he set off on his epic journey, Vivekananda finally achieved his aim of founding a social relief organisation, which he named after his mentor – the Ramakrishna Mission. The Mission and a new temple were established in Howrah, a suburb of his home town of Calcutta.

He returned to India a guru in the modern sense: a teacher with a significant international following. His success in the West did not go unnoticed in India, and his ‘journey’ was to become a model followed by the modern gurus and yogis who came after him.

Vivekananda in his sannyasin robes, probably taken at the newly created Belur Math in Howrah, 1899.

Vivekananda showed that it was possible to present yogic concepts and techniques to a wider audience by drawing on the modern influences around him. Most importantly, he demonstrated how South Asian ideas and traditions could be given universal appeal but still retain their identity, rather than simply being assimilated.

Modern yoga at the end of the 19th century was essentially Raja yoga, a spiritual, meditative practice. The revival of a more physical practice emerged in the early 20th century within the context of a broader physical culture movement that began in northern Europe and spread across the world.

About the author

Lalita Kaplish

Lalita is a digital content editor at Wellcome Collection with particular interests in the histories of science and medicine and discovering hidden stories in our collections.