Yogis and ascetics used to wander freely around South Asia, practicing martial arts alongside their yoga and providing armies for hire. And then the modern world caught up with them.

The yogi as hermit, warrior, criminal and showman

Words by Lalita Kaplishaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

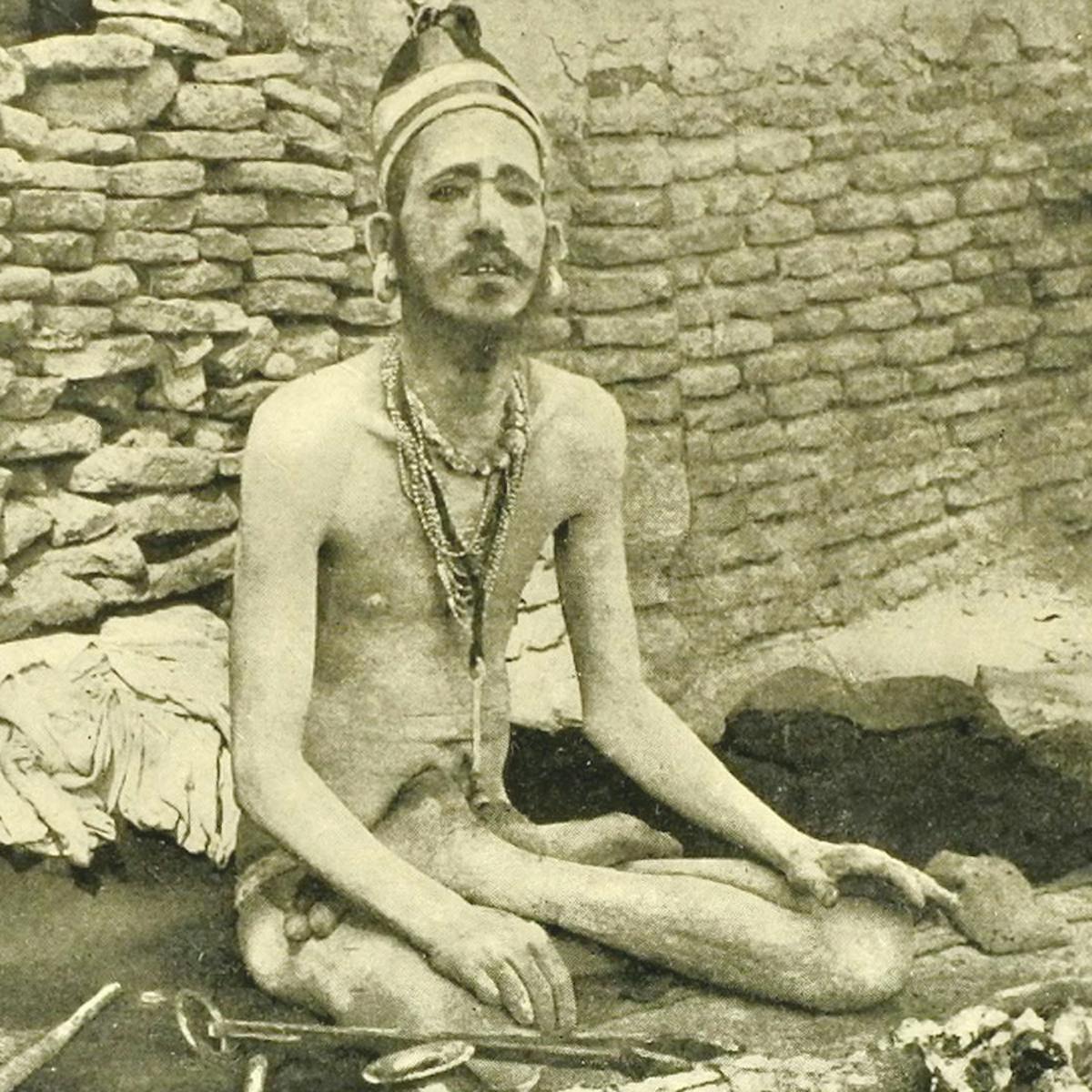

Very little is known about the yogi from Mirzapur (above), whose photo appears in a book called ‘The Mystics, Ascetics, and Saints of India(view in catalogue)’ (1905).

He is simply described as “lightly clad, smeared with ashes, and wearing a nadh (a wooden pipe)” and strings of beads around his neck. According to the author, the ‘pipe’ would have been sounded morning and evening and before eating or drinking anything.

By the end of the 19th century, this mysterious and “even dangerous” figure represented the archetypal Indian yogi. But there is far more to the yogi’s story than this iconic image.

Ascetics, people who renounce ordinary life for a simpler existence of abstinence or spiritual communion, are common across the religious traditions of the Indian subcontinent. Over time, these ascetics exchanged beliefs, including yogic practices.

Yogis – those who who practice yoga – might be Jain, Buddhist or Hindu. They may be male or female (yoginis). They may be devotees of one god or of several, or no god in particular.

Yogis and fakirs

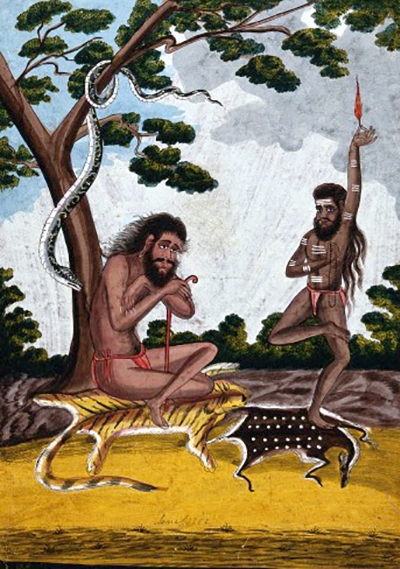

Two archetypal yogis. The white horizontal lines on the forehead suggest they are followers of the god Shiva. 1840.

A Vaishnav or Bairagi ascetic (right). Vaishnav ascetics (followers of the god Vishnu) are identified by the ‘V’ shaped mark on their foreheads. 19th century.

An ascetic in a saffron robe performing the ancient urdhvabahu penance of permanently keeping one arm raised.

A fakir from the Malabar coast, South India. The lettering describes him as a Muslim ascetic, who travels about, while the wife stays at home. 19th century.

Two female ascetics (yoginis) from Rajasthan, India. c.1730-1740.

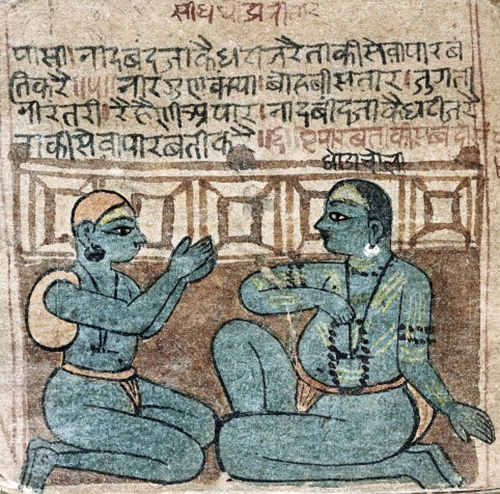

Two Nath yogis, identified by the necklace and horn around the neck. Later Nath yogis were also identified by the earrings pierced through the cartilage of the ear.

Sikh ascetics, Punjab, India.

A group of male and female sannyasis (Hindu ascetics). 1905.

Warrior monk

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, highly organised bands of ascetics controlled many of the trade routes in the north of the subcontinent. These ascetic militias often trained in yogic practices, as well as in martial arts. They battled with each other and provided mercenary armies for moguls, rajahs and wealthy landowners.

In 1567, the Mughal emperor Akbar encountered a battle between two rival groups of sannyasis (Hindu ascetics) at Thaneshwar. The chaotic scene was captured by his court artist, and shows the sannyasis with their wild hair and ashen blue skins fighting for the right to control a prime site on the banks of the Saraswati River.

The groups were gathered, along with other pilgrims, on the day of a solar eclipse to bathe in the river. The riverbank was a prime site for performing rites and collecting alms from the pilgrims.

Extract of ‘The Battle of the Sannyasis’, painted by Baswan, c.1590

The painting also highlights the growing numbers of rival factions of ascetics. The ascetics in the painting bear the mark of the Vaishnav sect (followers of the god Vishnu): a characteristic V or U shape on the forehead and nose. Their archrivals were the Shaivites, the followers of Shiva.

Battles between the military wings of Vaishnav sects such as the Ramanandis and Shaivite sects such as the Dasnami were at their most violent in the 18th century and resulted in the deaths of thousands of ascetics.

Colonial criminal

With the rise of the British East India Company in the 18th century, the economic and political power of moguls, rajahs and ascetic militias was challenged by British colonial expansion.

The colonists did not differentiate between yogis, Sufi fakirs, Hindu sannyasis or other ascetics. The terms began to be used interchangeably to describe a stereotypical wandering ascetic, notorious for his wild behaviour, begging and extreme practices.

The Company took over administrative control of the North-western province of Bengal after its army defeated the local ruler.

The Mughal emperor Shah Alam granting the rite of Diwani to Robert Clive, the governor of Bengal, which transferred tax collecting rights in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to the East India Company in 1765.

Organised groups, such as ascetic militias who had their own local economic and administrative systems, were a direct challenge to the Company's rule – and its profits.

In 1773, a ban was imposed on the wandering ascetics of Bengal. And it became an offence to wander naked or carry a weapon – the two defining characteristics of many ascetic groups – in British controlled areas (Singleton, p.40(view in catalogue)). The new law was supported by the local merchants and commercial elites who were reluctant to pay both British taxes and the road tolls demanded by ascetic militias. Many ascetics were effectively criminalised.

But the restrictions imposed by the colonial authorities did not go unchallenged by the more powerful ascetic groups. There were many clashes with the East India Company’s army. The Fakir and Sannyasi Rebellion of the 1770s inspired a novel, ‘Anandamath’ and the national song of India, ‘Vande Mataram’, was first published in this novel, making the ascetics an early part of the nationalist struggle against colonial rule.

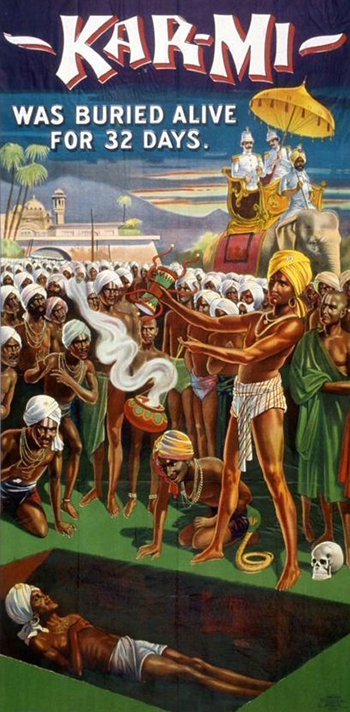

Kar-Mi was the stage name of American vaudeville performer Joseph Hallworth (1872-1956). His show posters “present KAR-MI as a prince of India and high priest of conjurers and spirit workers”. From The Strong National Museum of Play.

Exotic spectacle

No longer able to live by trade-soldiering, many ‘yogis’ were reduced to making a living through showmanship and begging. Others continued their non-militant activities on a smaller scale.

Ascetics remain a part of the spiritual tradition in the subcontinent to this day. Some travel the land on pilgrimage to holy sites, earning a living as rural priests performing religious rites and collecting alms on their journey. Others join religious orders, or settle in communities.

For colonial settlers and foreign visitors, yogis and fakirs were a source of fascination and fear. John Campbell Oman was an English colonial, born in Calcutta (Kolkata) in 1814. His book ‘The Mystics, Ascetics, and Saints of India(view in catalogue)’ (1905) is a traveller’s tale, reflecting many of the colonial views and attitudes towards ascetics around the end of the 19th century.

Oman was not unsympathetic to the changing world of the ascetic and observed how they were represented:

Their accentuated outward peculiarities have proved so attractive to the ubiquitous modern cameraman that his photographs and snapshots reproduced in popular pictorial magazines have made them, at least in their more uncouth forms, familiar to the Western world.

This photograph is described as “a fakir sitting on a bed of nails”. By R C Mazumdar, Benares, India, c. 1900.

The “uncouth form” of fakir or yogi was associated with fantastical feats, such as lying on a bed of nails or being buried alive. Such feats had their origins in the tapas (power)-inducing austerities of the tantric tradition. Once incorporated into carnival acts and magic shows around the world, they were stripped of their original cultural context.

By the end of the 19th century, the physical and martial practices of hatha yogis and other ascetic groups were declining along with the reputation of the yogi.

For Westerners, the yogi was a carnival curiosity or a sinister wild man. And in the subcontinent, he became a symbol of backwardness and suspicion from which a generation of modern Indians growing up under colonial rule were keen to dissociate themselves.

The forces of renunciation

Yet something about the ascetic tradition remained appealing.

Like many of his Western compatriots, Oman felt “no particular admiration for the modern industrialisation of Europe and America, with its vulgar aggressiveness, its eternal competition and its sordid, unscrupulous, unremitting and cruel struggle for wealth as the supreme object of human effort”.

Born and raised in Bengal, Oman was aware of the excesses of the East India Company – the first global corporation in the world – when he wrote these words. He realised that the subcontinent was on the verge of its own encounter with modernity, which would threaten the way of life of the ascetic as much as the armies of the East India Company had done in the past:

A momentous, if unobtrusive, struggle in India is inevitable under new conditions between the forces that make for renunciation of the world on the one hand and for the accumulation of wealth on the other.

East and West, there was a growing interest in new and alternative forms of spirituality. In the USA, Oman noted “a growing class of publications in which prominence is given to such subjects as… rapport with the Universal and also without disguise the Raja Yoga system of India”.

The ‘Raja Yoga’ Oman refers to a series of lectures published in the USA by a sannyasi called Vivekananda.

At the very end of the 19th century, Vivekananda set sail for America – a journey that would result in the renaissance of yoga as a universal practice available to all, and lead historians to describe him as “the creator of modern yoga(view in catalogue)”. But that’s another story.

About the author

Lalita Kaplish

Lalita is a digital content editor at Wellcome Collection with particular interests in the histories of science and medicine and discovering hidden stories in our collections.