In place of the large complexes we know today, London was once dotted with more than 500 small or specialist hospitals. Now converted or demolished, these buildings left clues to their presence, if you know where to look.

Hospitals are mysterious, self-contained places, but also central to our lives. They occupy a ritual role as the locations for the most extreme moments of human existence – birth, crises and death – as significant as churches once were. Yet, as buildings, they can be almost invisible, secondary to the functions they perform.

In London more than 500 hospitals have closed, most during the past century. The lost hospitals of London, from the showy high-Victorian complexes to the obscure, specialist hospitals that once dotted the city, retain a shadowy presence in familiar neighbourhoods.

The London streetscape I hold in my mind is punctuated by abandoned and converted Victorian hospital sites, peculiar medical buildings reassigned to new uses, and gaps where a presence lingers.

The meat-free medics

A small, oddly shaped park beside the New Kent Road in south London has lodged itself in the back of my mind. Within sight of the seething Elephant and Castle gyratory, it is a kink in the street line, creating an awkwardly sized space occupied by low-maintenance landscaping.

It stayed with me for years as unexplained, just one of the many leftover spaces strewn around London, but perhaps also a problem to be solved.

The missing piece clicked into place when I read about the long-closed Hospital of St Francis, patron saint of animals, once located at this spot. A remarkably radical institution for its time, the hospital had been founded in 1898 by a Dr Josiah Oldfield, on vegetarian principles. Oldfield was at university with Mahatma Gandhi, where they jointly founded the Fruitarian Society, and the two shared a flat in Bayswater.

The hospital allowed no meat in the building, which led to early resignations from staff who had not read the small print. This minor revolution in an unremarkable location was typical of the gloriously varied world of hospitals operating in London right up until the foundation of the National Heath Service in 1948.

In the pre-NHS era, healthcare was localised, specialised and particular to place.

Very specialist services

Londoners are now served by huge, city-within-a-city hospital complexes, but until 1948 they were treated instead by a multitude of institutions, each with their own peculiarities and funding arrangements. In the pre-NHS era, healthcare was localised, specialised and particular to place.

Much healthcare in the capital served specific groups or afflictions, a conceptually flawed system that saved the few at the expense of the many. Many hospitals were one-offs, set up by those who could raise the money, surviving on regular appeals for funds. This resulted in an eccentric range of institutions, a scenario that is now almost impossible to imagine but is marked all around us.

Some institutions were intended for a particular community, for example the French Protestant Hospital in Hackney, a chateau-like building funded by wealthy Huguenots to serve fellows in need, or the Italian Hospital in Bloomsbury which, with only 50 beds, served inhabitants of Little Italy who did not speak English.

MORE: How the architecture of London's Barbican Estate inspires poetry

Many hospitals were set up by charities with their own priorities, some more overt than others. The Magdalen Hospital for Penitent Prostitutes in Streatham, for example, was a reform home that did not hide its agenda, while the Young Leaguers Union Hospital in Highgate was established by a Methodist fundraising brigade.

Some lasted longer than seems possible. The Royal Masonic Hospital in Hammersmith survived the 1948 reorganisation and folded only in 1994. A year later, the Jewish Home and Hospital for Incurables in Tottenham, a specialist home for those with severe disabilities, closed because the once large Jewish population of Tottenham had moved away.

Lost hospitals of London - in pictures

Some of London’s best-known hospitals can be found in earlier, smaller incarnations in unexpected locations: the Royal Free Hospital buildings on Liverpool Road, converted to housing.

Treating the weakest

Hospitals with particularly poignant remits were aimed at the most vulnerable: the Home for Confirmed Invalids in Highgate, the Home for Little Sick Babies in Hoxton – a tiny 12-cot institution – or the Sanatorium for Sick Governesses in Lisson Grove, also known as the Florence Nightingale Hospital for Ladies of Limited Means, which was managed in its early days by the great lady herself.

The more esoteric end of the spectrum included institutions that pursued a particular line in treatment, such as the Institute of Ray Therapy in Camden, which offered treatment using ultraviolet and infrared lamps, and electrical currents.

Oldfield’s Hospital of St Francis fell firmly into this category. However, it survived after merging with the Anti-Vivisection Hospital in Battersea, which became part of the NHS and operated until 1972. Oldfield himself went on to found the first and only fruitarian hospital in Britain in Bromley and later, destroying his reputation, to become a proponent of eugenics.

All these were voluntary hospitals, funded by charities or benefactors and closely tied to their locations and the people they served. The creation of the NHS marked the end of institutions such as these, as hospitals in England and Wales were placed under the oversight of regional hospital boards.

The introduction of a universal service put paid to selective healthcare provision and transformed services in Britain. However, because the system it replaced was so extensive, the remnants of the pre-war hospital landscape have yet to fade away, decades later.

Hospitals on every street

The history of the central London hospital is often that of institutions set up in adapted houses, located on high streets like any other shop. Health historian Professor Nick Black observes in his guidebook ‘Walking London’s Medical History’ that in London “healthcare is everywhere”. leaving its mark on the majority of central London streets. Lost hospitals are planted across the city in plain sight, under new guises or as derelict sites that have mislaid their original purpose.

Until its demolition in 2017 for the High Speed 2 railway line, I passed the long-abandoned Temperance Hospital on the Hampstead Road every day on my way to work. Its balconied walkways were boarded up and its foundation stone, laid on Thursday 24 September 1884 and now shrouded in buddleia, declared “Blessed are the Merciful”. It was the most intriguing, characterful and mysterious building on the street, and the only one guaranteed to vanish.

Other sites, empty for years, have been redeveloped in the last ten years as underused land has become an asset no one can afford to ignore. However, the Samaritan Hospital for Women on Marylebone Road is still standing in late 2018, having lain empty for a decade, a stark memento mori in an area where every building is otherwise in intensive use.

Whispers of the past

Like many discarded pieces of city, the small park by the New Kent Road conceals layered memories. The Hospital of St Francis that briefly bordered this overlooked space was a tiny part of a vast patchwork that has left its traces all around us, whether we know it or not.

The NHS improved medical services immeasurably and no one, surely, would want to go back to what was before. However, places that have seen so much human emotion do not disappear easily. The places where people suffered still speak in a muttering undercurrent, audible only when we stop to listen.

About the contributors

Dr Tom Bolton

Dr Tom Bolton is a researcher, and the author of five books, including ‘London’s Lost Rivers Volumes 1 & 2’, ‘Low Country: Brexit on the Essex Coast’ and ‘Vanished City: London’s Lost Neighbourhoods’. His work has been published in the Guardian, the Daily Telegraph and Londonist.

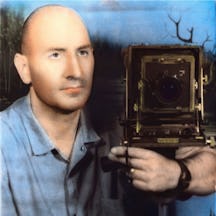

Simon Norfolk

Simon Norfolk is a photographer who regularly contributes to National Geographic and has shown his work at Tate Modern. He specialises in post-conflict landscapes; in particular he has worked a great deal in Afghanistan. His most recent book was following in the steps of the 19th-century photographer of the Second Afghan War, John Burke. Simon is currently running at a pretty nifty Number 44 on ‘The 55 Best Photographers of all Time. In the History of the World. Ever. Definitely’.