Stories

- Article

Building a dream in the garden suburbs

In the late 19th century a ‘garden suburb’ promised a retreat from London’s dirt and crowds. See how this new concept was developed to appeal to the health concerns of the literary classes.

- Article

How we bury our children

Following her baby daughter’s funeral, Wendy Pratt found that visiting the grave gave her a way to carry out physical acts of caring for her child. Here she considers how parents’ nurturing instincts live on after a child’s death.

- Article

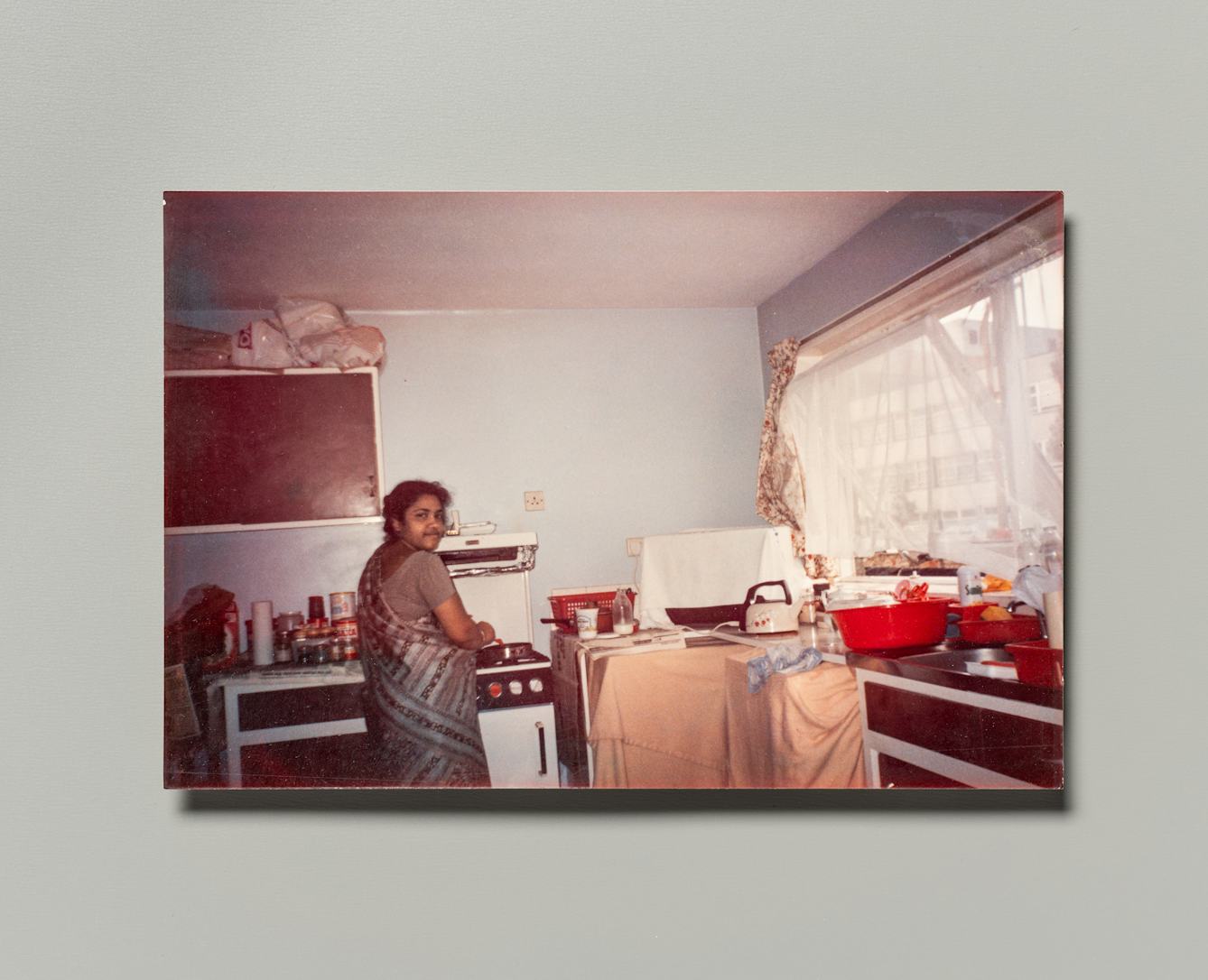

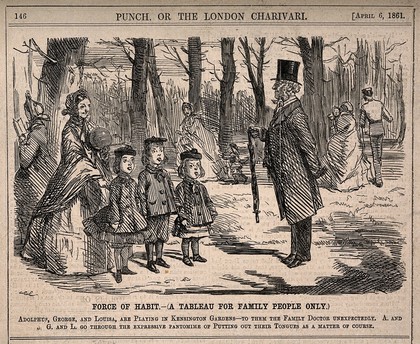

Doctor in the house

A house is not always a home – sometimes it’s impermanent, impersonal. But other aspects of the itinerant life can be the source of a sense of home.

- Article

Cowpox, Covid-19 and Jenner’s vaccination legacy

The well-known story of vaccination pioneer Edward Jenner has at its heart his drive to make vaccines free of charge and available to all. Now his principles extend to the global campaign for a people’s patent-free vaccine for Covid-19.

Catalogue

- Books

Gardening for children with autism spectrum disorders and special educational needs : engaging with nature to combat anxiety, promote sensory integration and build social skills / Natasha Etherington.

Etherington, NatashaDate: 2012- Books

Generations gardening together : sourcebook for intergenerational therapeutic horticulture / Jean M. Larson, Mary Hockenberry Meyer.

Larson, Jean M.Date: [2006]- Books

- Online

A proposal for employing, cloathing, and furnishing, with implements of husbandry, children, from the age of ten to sixteen; with a view to agriculture, the improvement of land, and gardening. Addressed to the Dublin Society. By Sir James Caldwell, baronet.

Caldwell, James, Sir, -1784.Date: 1770- Books

- Online

A proposal for employing, cloathing, and furnishing, With the implements of husbandry, children, from the age of ten to sixteen; with a view to agriculture, the improvement of land, and gardening. Addressed to the Dublin Society. By Sir James Caldwell, baronet.

Caldwell, James, Sir, -1784.Date: MDCCLXXI. [1771]- Books

- Online

A thousand more notable things: or, modern curiosities. Viz. Divers physical receipts. Monthly observations in gardening, Planting and Grafting. To prevent diseases in children. Directions for all midwives, Nurses, and Child-Barring Women. Problems of Aristotle. A Book of Knowledge. The Art of Angling. The Art of Japanning. Rules of Health & Long-Life. Rules for Blood-Letting. To make the Face beautiful. Reasons of Thundering and Lightning. How to destroy Vermin. To order Children rightly, and to prevent Diseases incident to them. The Art of Painting in Oyl. Curious Inventions for the Ingenious to improve on. To cure all Diseases in all sorts of Cattel. With divers other Curiosities. By G. Johnson. Part II.

Date: [1706?]

![Paeonia officinalis L. Paeoniaceae, European Peony, Distribution: Europe. The peony commemorates Paeon, physician to the Gods of ancient Greece (Homer’s Iliad v. 401 and 899, circa 800 BC). Paeon, came to be associated as being Apollo, Greek god of healing, poetry, the sun and much else, and father of Aesculapius/Asclepias. Theophrastus (circa 300 BC), repeated by Pliny, wrote that if a woodpecker saw one collecting peony seed during the day, it would peck out one’s eyes, and (like mandrake) the roots had to be pulled up at night by tying them to the tail of a dog, and one’s ‘fundament might fall out’ [anal prolapse] if one cut the roots with a knife. Theophrastus commented ‘all this, however, I take to be so much fiction, most frivolously invented to puff up their supposed marvellous properties’. Dioscorides (70 AD, tr. Beck, 2003) wrote that 15 of its black seeds, drunk with wine, were good for nightmares, uterine suffocation and uterine pains. Officinalis indicates it was used in the offices, ie the clinics, of the monks in the medieval era. The roots, hung round the neck, were regarded as a cure for epilepsy for nearly two thousand years, and while Galen would have used P. officinalis, Parkinson (1640) recommends the male peony (P. mascula) for this. He also recommends drinking a decoction of the roots. Elizabeth Blackwell’s A Curious Herbal (1737), published by the College of Physicians, explains that it was used to cure febrile fits in children, associated with teething. Although she does not mention it, these stop whatever one does. Parkinson also reports that the seeds are used for snake bite, uterine bleeding, people who have lost the power of speech, nightmares and melancholy. Photographed in the Medicinal Garden of the Royal College of Physicians, London.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/B0009095/full/282%2C/0/default.jpg)

![Paeonia officinalis L. Paeoniaceae, European Peony, Distribution: Europe. The peony commemorates Paeon, physician to the Gods of ancient Greece (Homer’s Iliad v. 401 and 899, circa 800 BC). Paeon, came to be associated as being Apollo, Greek god of healing, poetry, the sun and much else, and father of Aesculapius/Asclepias. Theophrastus (circa 300 BC), repeated by Pliny, wrote that if a woodpecker saw one collecting peony seed during the day, it would peck out one’s eyes, and (like mandrake) the roots had to be pulled up at night by tying them to the tail of a dog, and one’s ‘fundament might fall out’ [anal prolapse] if one cut the roots with a knife. Theophrastus commented ‘all this, however, I take to be so much fiction, most frivolously invented to puff up their supposed marvellous properties’. Dioscorides (70 AD, tr. Beck, 2003) wrote that 15 of its black seeds, drunk with wine, were good for nightmares, uterine suffocation and uterine pains. Officinalis indicates it was used in the offices, ie the clinics, of the monks in the medieval era. The roots, hung round the neck, were regarded as a cure for epilepsy for nearly two thousand years, and while Galen would have used P. officinalis, Parkinson (1640) recommends the male peony (P. mascula) for this. He also recommends drinking a decoction of the roots. Elizabeth Blackwell’s A Curious Herbal (1737), published by the College of Physicians, explains that it was used to cure febrile fits in children, associated with teething. Although she does not mention it, these stop whatever one does. Parkinson also reports that the seeds are used for snake bite, uterine bleeding, people who have lost the power of speech, nightmares and melancholy. Photographed in the Medicinal Garden of the Royal College of Physicians, London.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/B0009094/full/600%2C/0/default.jpg)