In the 19th century, electricity held life in the balance, with the power to execute – or reanimate.

The current that kills

Words by Ruth Gardeaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Serial

The devastating power of electricity gave good cause for the unease and fear it evoked. And yet the risk of lethal injury was what made it so fascinating and its displays so sensational. Cases such as that of the Russian professor Georg Wilhelm Richmann, killed by lightning while experimenting with atmospheric electricity, emphasised the dangers of dabbling in this new field. But these horrifying stories also offered a piquant thrill.

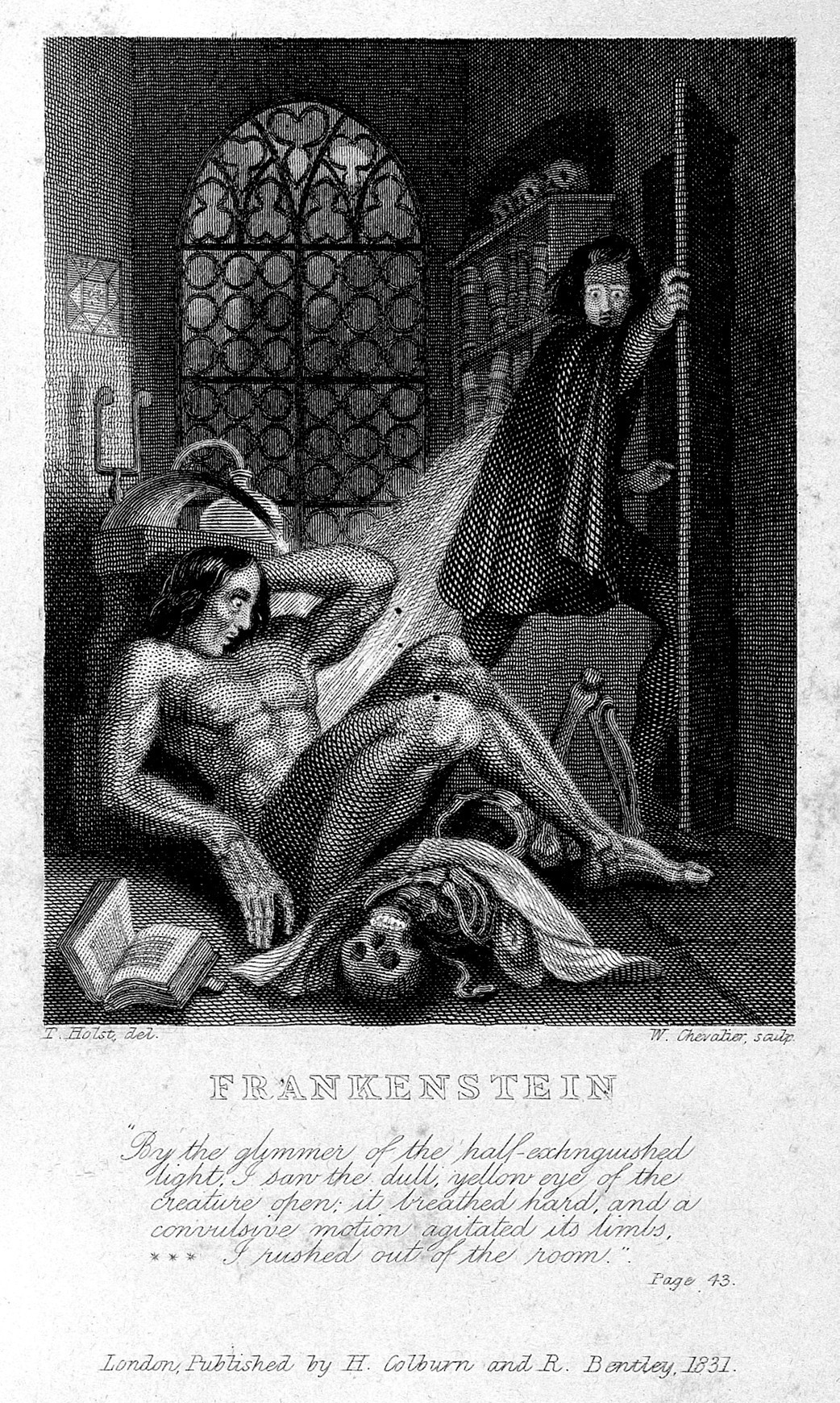

Though not explicitly referenced in the novel, galvanic experiments inspired in Mary Shelley’s imagination the possibilities of reanimating a corpse.

Electricity could kill; but it could, according to some, also resurrect. In the mid-18th century, physicians discovered that forcing air into the lungs could resuscitate people who were apparently dead. With the frontier between life and death appearing porous, some hoped that electricity could bring the dead back to life.

Eusebio Valli, an Italian physician, performed electrical experiments across Europe on amputated human limbs as well as on various species of animals, which he attempted to revive. But the most revealing experiments were thought to be those carried out on the bodies of the newly dead, since they could help to determine the nature and extent of consciousness as well as the value of electricity as a tool of resuscitation.

A number of physicians began to attend executions by guillotine to get access to the freshest corpses. Some experimenters concluded that a capacity for awareness survived after beheading and that the guillotine was therefore an inhumane form of execution. This apparent residual post-mortem electrical activity further blurred the boundaries between life and death.

In pictures

![Jacksonian editor Francis Preston Blair rises from his coffin, revived by a primitive galvanic battery, as two demons look on. A man on the right throws up his hands as he is drawn toward Blair, saying: Had I not been born insensible to fear, now should I be most horribly afraid. Hence! horrible shadow! unreal mockery. Hence! And yet it stays: can it be real. How it grows! How malignity and venom are "blended in cadaverous union" in its countenance! It must surely be a "galvanized corpse." But what do I feel? The thing begins to draw me . . . I can't withstand it. I shall hug it! . . . First demon: "There! We've lost him, after all! See! they are bringing him to life again!" Second demon (holding a copy of Blair's newspaper, the "Globe)": Lose him! ha ha! . . . Rest you easy on that score. But can't you see that it's all for our gain that he should be galvanized into activity again? Where have we his equal on earth? especially since dear Amos [Kendall], poor fellow, has got his hands so full, at the Post Office, that he can't write for us as he used to. Show me another man that can lie like him. They talk of Croswell [influential editor of the "Albany Argus" and Van Buren ally Edwin Croswell] but Harry is nothing to him. I doubt if I can beat him myself. Lose him! a good joke that! Weitenkampf tentatively identifies the man at right as Amos Kendall, but the likeness differs considerably from that found in other caricatures of Kendall.](https://images.prismic.io/wellcomecollection/0fae59337b37a18c30abb7f9f95798f6fc686fd0_current-1.jpg?w=960&auto=compress%2Cformat&rect=&q=100)

Galvanic experiments evidently provided a source for macabre comedy as well as gothic drama.

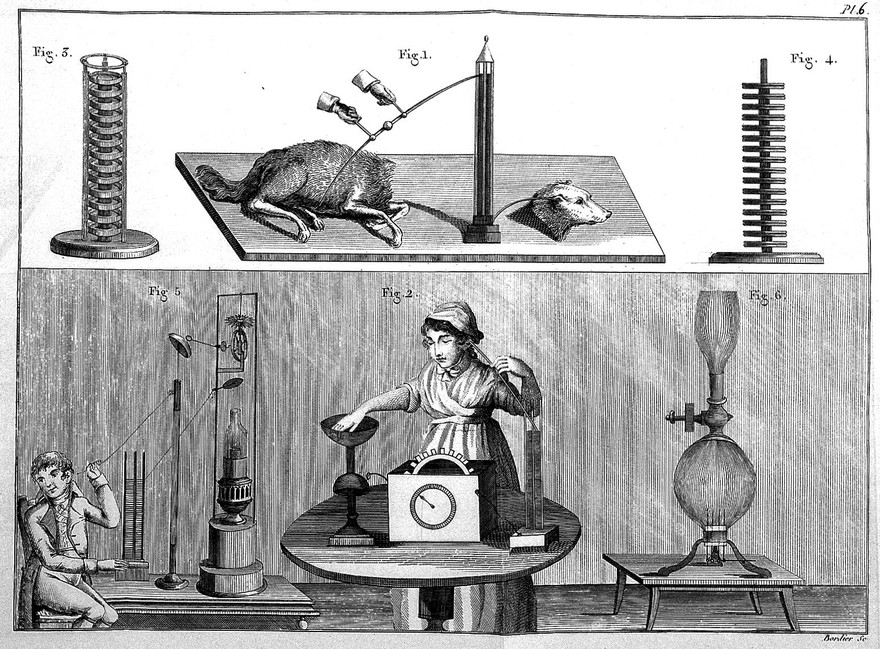

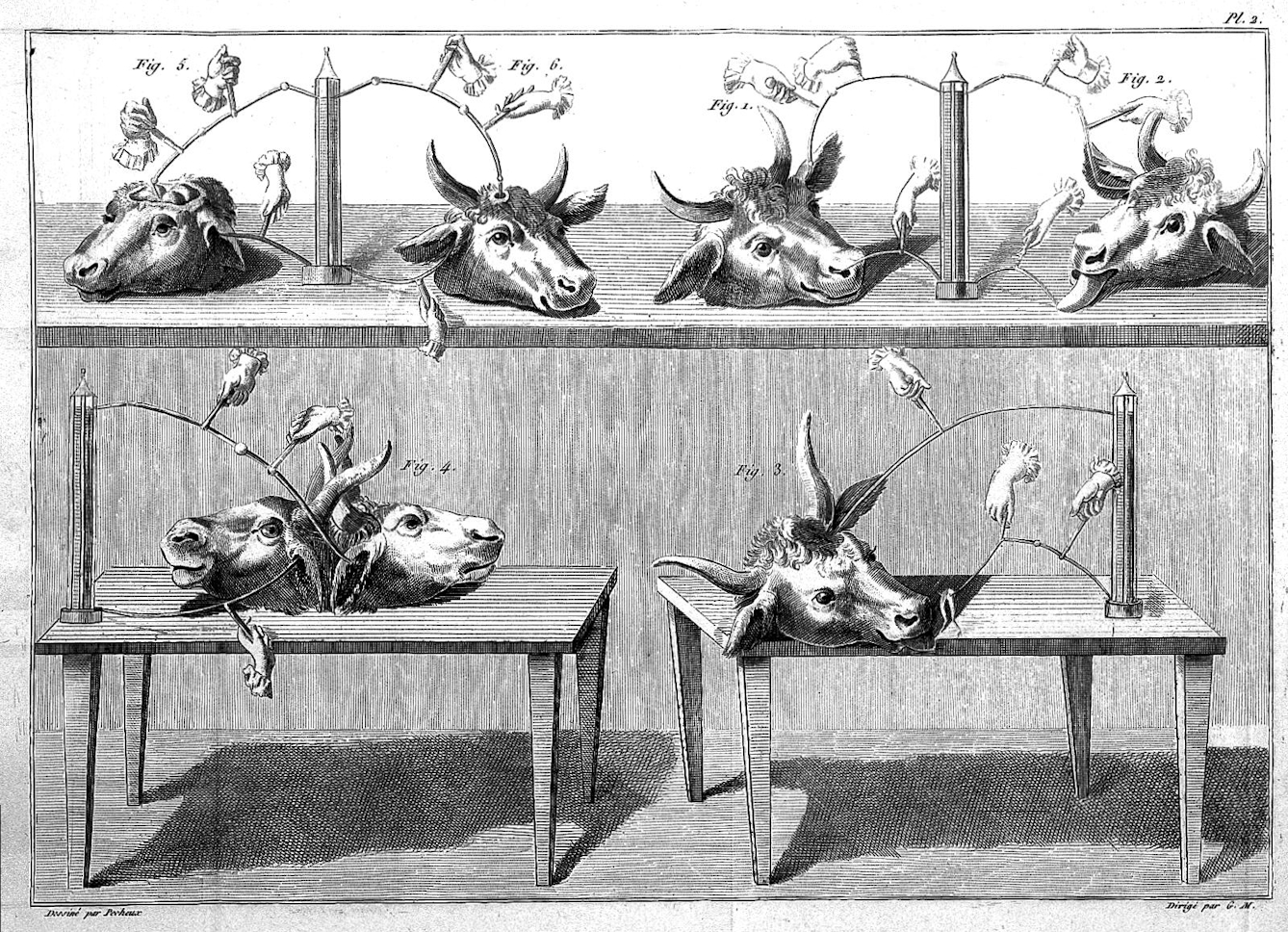

The slender stacks on either side of the dog’s body are voltaic piles, an early form of battery.

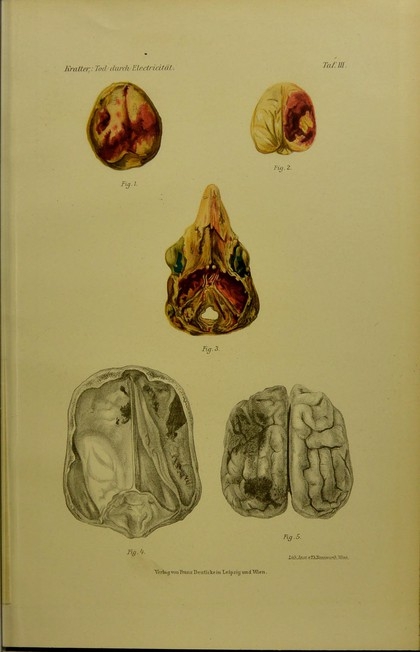

Julius Kratter observed the injuries sustained by various small animals (including a rabbit and a dog) after electrocution.

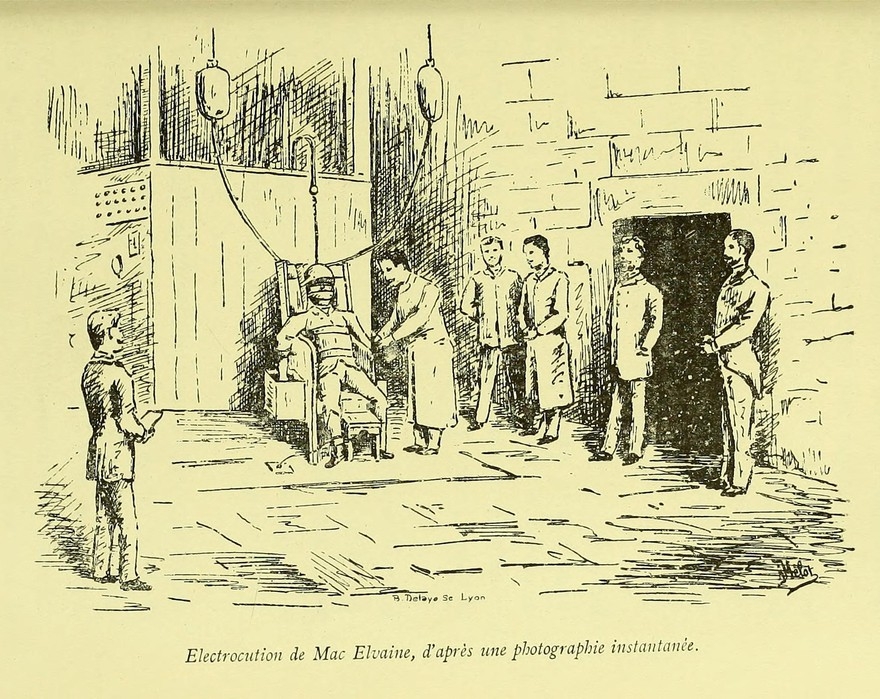

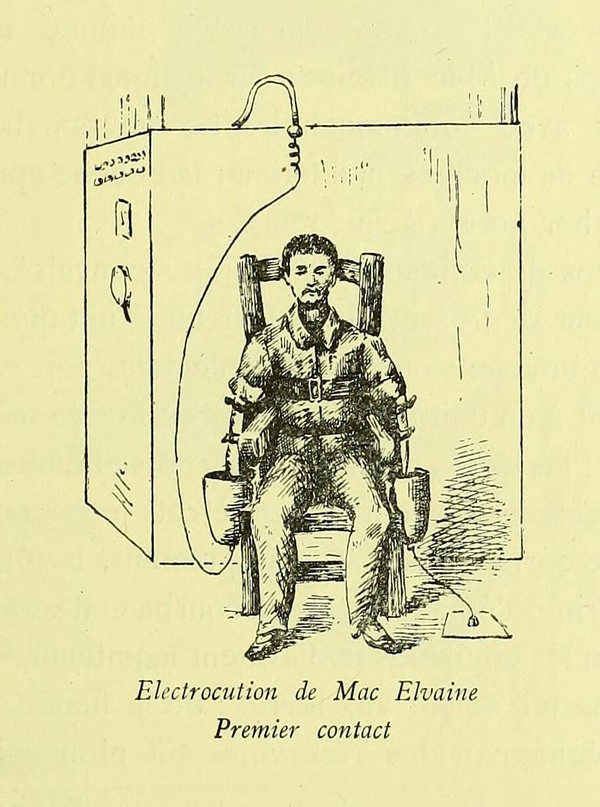

Charles MacElvaine, executed at Sing Sing prison in 1892, with his hands strapped in buckets of salt water.

This execution technique, devised by Edison, caused the convict to lose consciousness before the fatal shock was administered in another chair.

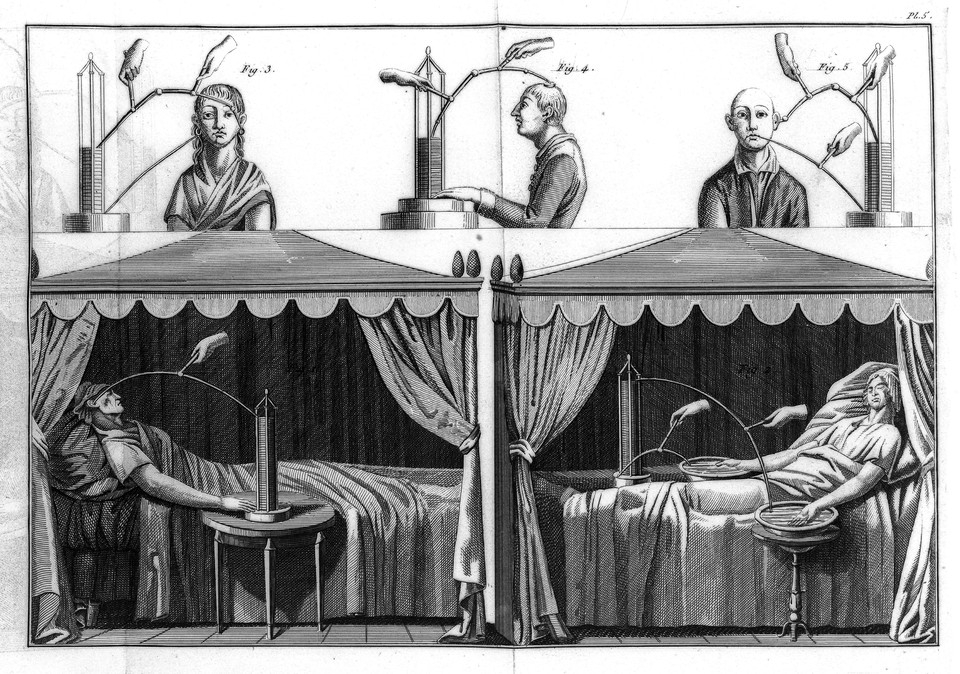

Aldini’s experiments led him to explore galvanism as a medical treatment, including for mental disorders.

Animals – either alive or dead, and often dissected – were routinely used in various galvanic experiments.

Giovanni Aldini, nephew of Luigi Galvani (the Italian scientist who studied animal electricity using amputated frogs’ legs), became known for his sensational demonstrations on human and animal corpses. In late 1802 he travelled to Paris, where he performed experiments on guillotined criminals and large animal carcasses before huge crowds. His demonstration using an ox produced such bodily convulsions that “several of the spectators were much alarmed, and thought it prudent to retire to some distance”.

In 1803 Aldini arrived in London, where his experiments at the Royal Society on the body of the hanged criminal George Forster became notorious. On the application of a current to the face, Forster’s left eye opened; when another was applied from the ear to the rectum, it produced such a powerful reaction as “almost to give an appearance of reanimation”.

Such experiments may have provided inspiration for Mary Shelley in her 1818 novel ‘Frankenstein’, where the doctor assembles his monster from stolen body parts and manages to “infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing”. Edgar Allan Poe used galvanic reanimation as a plot device to comic effect in his 1845 short story ‘Some Words with a Mummy’, in which an Egyptian mummy is shocked into life.

The associations between electricity and death emerged with the lethal power of lightning, an enduring symbol or omen of destruction.

The deadly power of electricity continued to loom large in the public imagination throughout the 19th century. In New York, where overhead cables were the norm (despite laws requiring underground wiring), cases of accidental electrocution began to emerge. Even while provoking consternation, such accidents provided ghoulish fascination. John Munro’s 1893 book ‘The Romance of Electricity’ devoted a dozen pages to graphic descriptions of well-known deaths by electrocution and included several illustrations of injuries to bodies and burnt clothing.

The 1890s also saw a development that many came to regard as the most sinister example of electricity’s deadly potential: the electric chair. In response to a growing sentiment in the US that hanging was a barbaric form of capital punishment, electric current was eventually sanctioned as a humane – yet still fearsome – alternative.

According to the author of the Execution Bill, “Criminals would infinitely more dread a silent going away – to be deliberately killed by a terrible but silent force to them unknown.” Park Benjamin, a prominent writer on electricity, agreed, explaining that “the instant extinction of life in a strong man by an agency which it is impossible to see, which is unknown, may create in the ignorant mind feelings of the deepest awe and horror, and prove the most formidable of all means for preventing crime”.

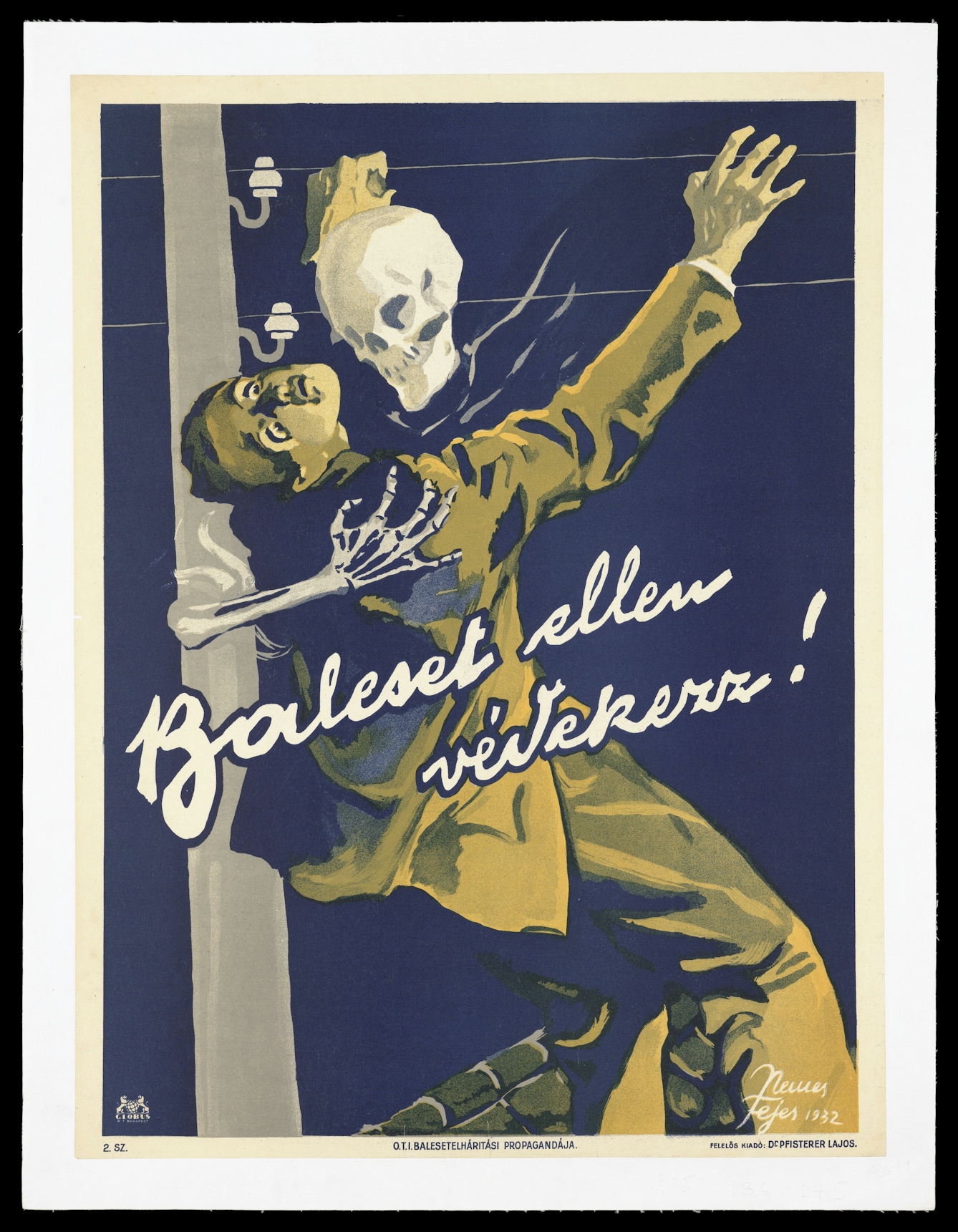

The lethal dangers of electrical innovations prompted the design of safety warnings, such as this Hungarian poster cautioning against climbing telegraph poles.

The first electrocution of a criminal, in 1890, gave the lie to these observations. William Kemmler required two prolonged shocks to die, during which he foamed at the mouth, groaned and convulsed, all accompanied by the smell of burning hair and flesh, urine and faeces. Witnesses vomited, cried and fainted.

The horror of the electric chair was co-opted by Walford Bodie, stage hypnotist and showman, in his turn-of-the-century performances. With the original chair used in Kemmler’s execution as a prop, Bodie would strap a volunteer in and hypnotise him to ‘protect’ him from the high voltage. During the mock execution the volunteer would twitch, shake and shriek, while being subjected to a non-lethal electric charge. The crowds reacted with predictable terror and revulsion. The awe of electricity could be inspired by its darkest, as well as its brightest, manifestations.

About the author

Ruth Garde

Ruth Garde is a freelance curator and writer, focusing on the fields of history, art, architecture and heritage. Over the past fourteen years she has worked extensively with Wellcome Collection, writing and curating a variety of projects encompassing history, human health, art and science.