The terms we use to describe the damage we inflict on our hands reveal trends in work and hobbies. Occupational therapist María Cristina Jiménez explores the language of hand injuries from the past and present.

For occupational therapists like me, ‘occupation’ means everything we do that occupies our time and our minds, including activities we need to do for a living. Injuries are not an isolated insult to a part of someone’s body; they occur to a whole person, who is part of a context, living and working at a specific moment in time.

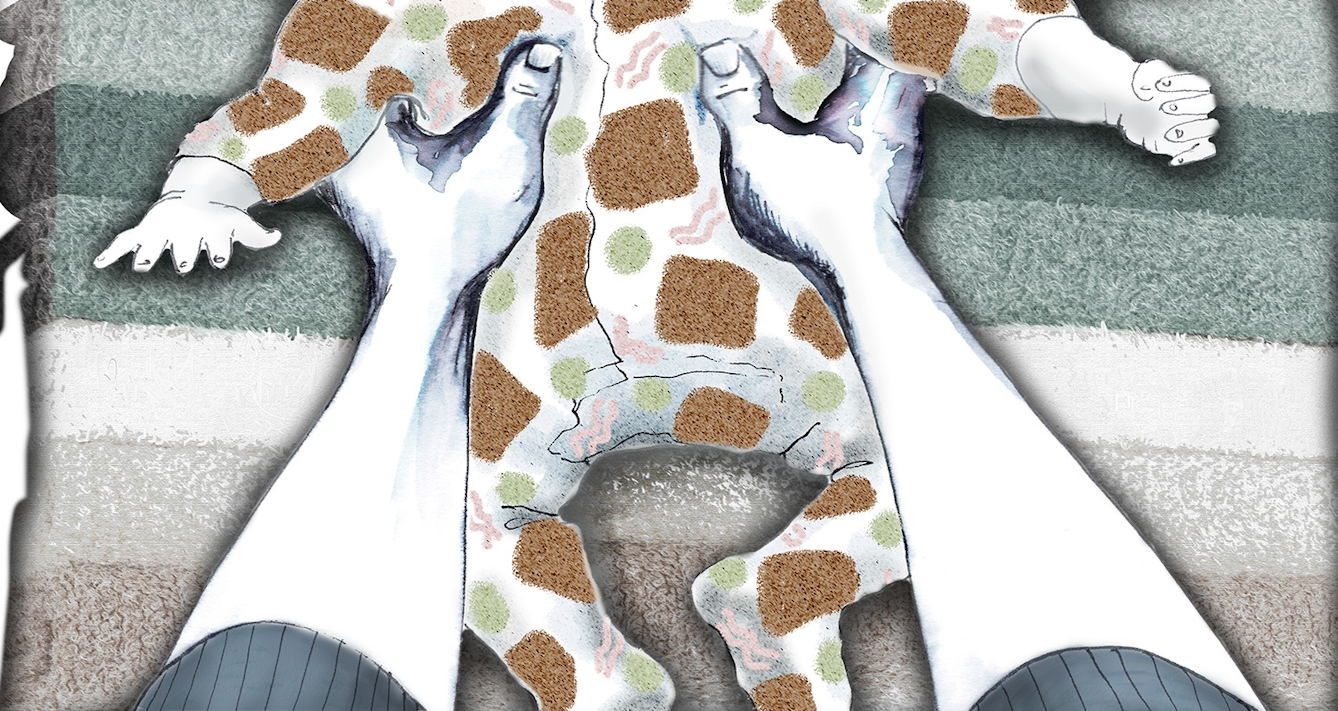

What occupies us and causes wear and tear isn’t always our day jobs, though. Recently, I saw a patient who was a 34-year-old janitor at a thrift store. He had first started experiencing sharp thumb pain a few months earlier. When I asked what his hands did most of the day, I assumed he’d talk about heavy lifting at work, but instead he mentioned he’d been taking care of his newborn baby. “It sounds like you have mother’s thumb,” I said, to his surprise.

“Mother’s thumb” is known as such because it is an injury commonly seen in mothers of babies, who experience pain from picking up their growing babies throughout the day by grabbing them with outstretched thumbs. I told my patient that even though the condition is referred to as “mother’s thumb” fathers can get it, and grandparents too.

The history of a name

This tendonitis of the thumb is more formally known as De Quervain’s tenosynovitis (DQT). Named after Fritz de Quervain, a Swiss surgeon who first identified it, DQT is an inflammation of the shealth around the two tendons of the thumb.

“I told my patient that even though the condition is referred to as “mother’s thumb” fathers can get it, and grandparents too.”

To confirm my patient’s diagnosis, I observed and felt his hand and thumb, then had him perform hand manoeuvres called “provocative tests” to see if they increased his symptoms, including one named after an American surgeon (Finkelstein’s test) and another named after a German doctor (Eichhoff’s test).

Many hand injuries, and the provocative tests to diagnose them, were named after white European, upper-class male doctors. But these terms aren’t the names we use in everyday life, which evolve over time, becoming colloquialisms.

When de Quervain first described the condition back in 1895, he called it “washer-woman’s sprain”. Over the next 100 years, DQT has also been referred to as: mothers’ thumb, designer thumb, Blackberry thumb, gamer’s thumb and now texter’s thumb. The evolution of these names tells a story about a condition that initially impacted women (which is still the case), but now overwhelmingly impacts all of us who text constantly.

From gamekeeping to gaming

Other conditions get renamed based on the way occupations, pastimes and habits change with technology.

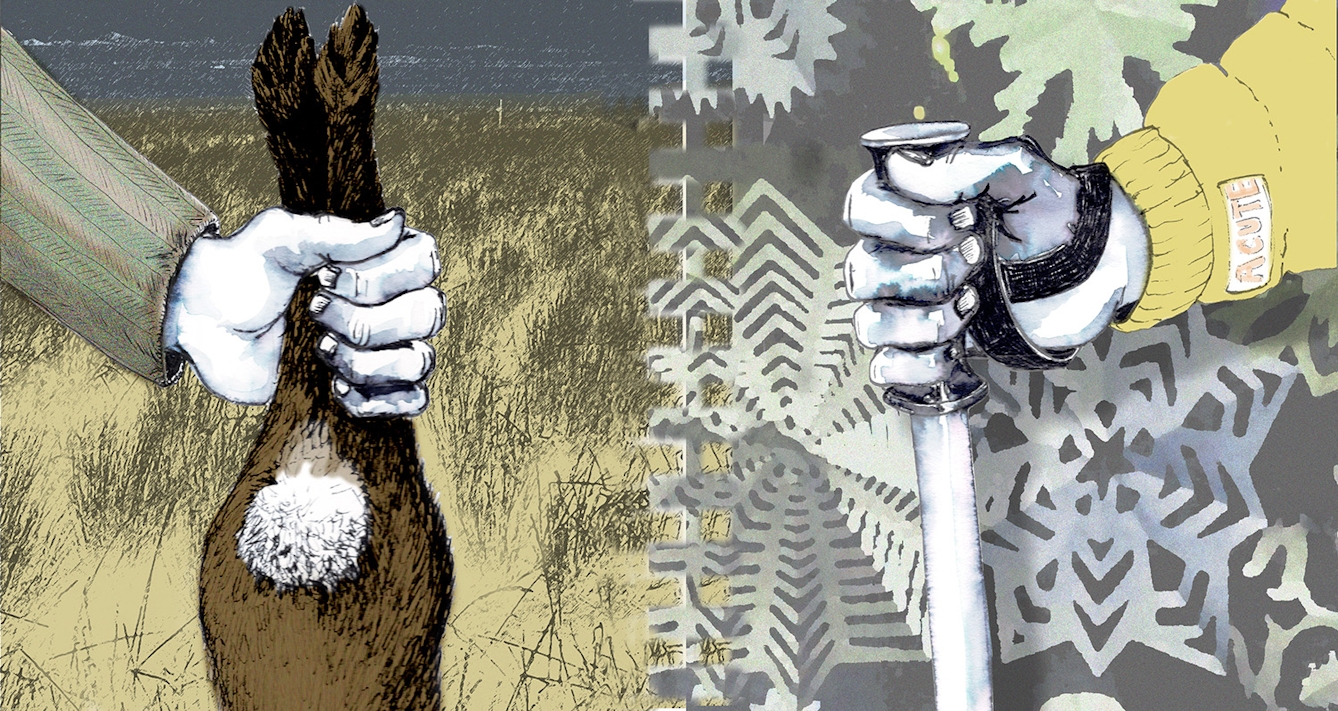

Originally coined by orthopaedic surgeon C S Campbell in 1955, “gamekeeper’s thumb” was an occupational injury associated with Scottish gamekeepers, who would grab a rabbit’s neck between their thumb and forefinger to break it against the ground. Over time the gamekeepers ruptured a ligament on the side of their thumb, resulting in pain, and weakness of their thumb.

“Skier’s thumb is an acute tear of a ligament, while gamekeeper’s thumb was a chronic injury made worse over time due to the repetitive nature of the work.”

Nowadays the term is used interchangeably with “skier’s thumb”, due to the common injury among downhill skiers, who fall with their outstretched thumb holding a ski pole. Technically they are different conditions: skier’s thumb is an acute tear of a ligament, while gamekeeper’s thumb was a chronic injury made worse over time due to the repetitive nature of the work.

Regardless of how the injury was obtained, if it is not treated promptly, the condition leads to difficulty in pinching and grasping objects. For a brief moment during the 1980s, this same injury was also known as “break-dancer’s thumb”.

Injuries like mother’s thumb and gamekeeper’s thumb are renamed over time as they become associated with new causes, but sometimes our changing occupations lead to injuries with interesting names vanishing completely. Hutchinson’s fracture was initially named after British surgeon Jonathan Hutchinson, who first identified it, but it was better known as “chauffeur’s fracture”.

When automobiles were first invented in the late 1800s, a new occupation emerged too: the chauffeur was the driver responsible for starting the engine (the word chauffeur is from the French verb “to heat”). Along with the new technology and a new career came a new injury. Chauffeur's fracture was a painful thumb-sided wrist fracture that happened when manually cranking engines, which would then backfire. As the car backfired, the crank smashed into the driver’s wrist, causing trauma.

Once automobiles became automatic, chauffeur's fracture as a condition disappeared.

“Chauffeur's fracture was a painful thumb-sided wrist fracture that happened when manually cranking engines, which would then backfire.”

Wrist fractures – especially distal radius fractures – remain common injuries to this day among older adults, due to falling and landing on an outstretched hand. These injuries are known by the much less interesting name Colles fractures, named after the Irish anatomy and surgery professor Abraham Colles, who first described them, years before X-rays were invented.

Harm to our hands today

Recently, as many people have been away from their employment due to lockdown, domestic hand accidents have been on the rise. A French epidemiological study compared emergency visits related to hand-trauma cases between 2019 and 2020 and found an increase in upper-limb and hand injuries during periods of lockdown in 2020.

Dr Sanjeev Kakar, an orthopaedic surgeon from the Mayo Clinic, observed an increase in domestic hand injuries as people took on DIY projects, and spent more time in the garden and kitchen.

My colleagues now see more injuries acquired gradually, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, cubital tunnel syndrome and lateral epicondylitis, which we more often call “tennis elbow”. These stem from home-working setups with poor ergonomics. We are overusing our keyboards with poor placement of our arms and hands during our work day.

From lockdowns to avocado-based-accidents, distinct characteristics of our time make their mark on our hands. They tell a story about our lives, which means they also tell us about history, gender and class. Hands are how we interact with the world, shaping the connective tissue of our history.

About the contributors

María Cristina Jimenez

María Cristina Jiménez is originally from Puerto Rico and is a certified and registered Occupational Therapist specializing in hand therapy. She’s also a Certified Advanced Rolfer®. Jiménez works part time at an outpatient hand clinic in Southern California, as well as sees clients in her home office. She is also a poet and writer.

Louise Hinman

Louise Hinman is a professional artist based in between Brighton, London and Tarragona in Spain. With over 20 years of drawing, painting, illustration, teaching and exhibition experience, she works on a wide variety of projects in many styles and genres for professional clients as well as personalised commissions. After initially studying Fine Art, with a focus on drawing and installation, she studied in London to specialize in Medical Art and became a member of the professional organisations; MAET, MAA and AEIMS. She also has a history of working in the charity sector and also works as the South East Public and Patient Involvement Coordinator for the NIHR Research Design Service SE.