The live spectacle of public surgery – and the origin of the operating ‘theatre’ – began with dissections for paying audiences in the 16th century. Lizzie Enfield uncovers the drama, and the developments that eventually sent surgical extravaganzas behind sterile closed doors.

The original drama of operating theatres

Words by Lizzie Enfield

- In pictures

Anyone who has ever watched a medical drama involving surgeons will know that operating theatres are clean, pristine, limited-access places. While we might enjoy the drama of someone being cut open on our TV screens, the word ‘theatre’ to describe the rooms where surgery takes place seems a little paradoxical. But 500 years ago, surgery took place in very different circumstances, performed to packed crowds in public spaces.

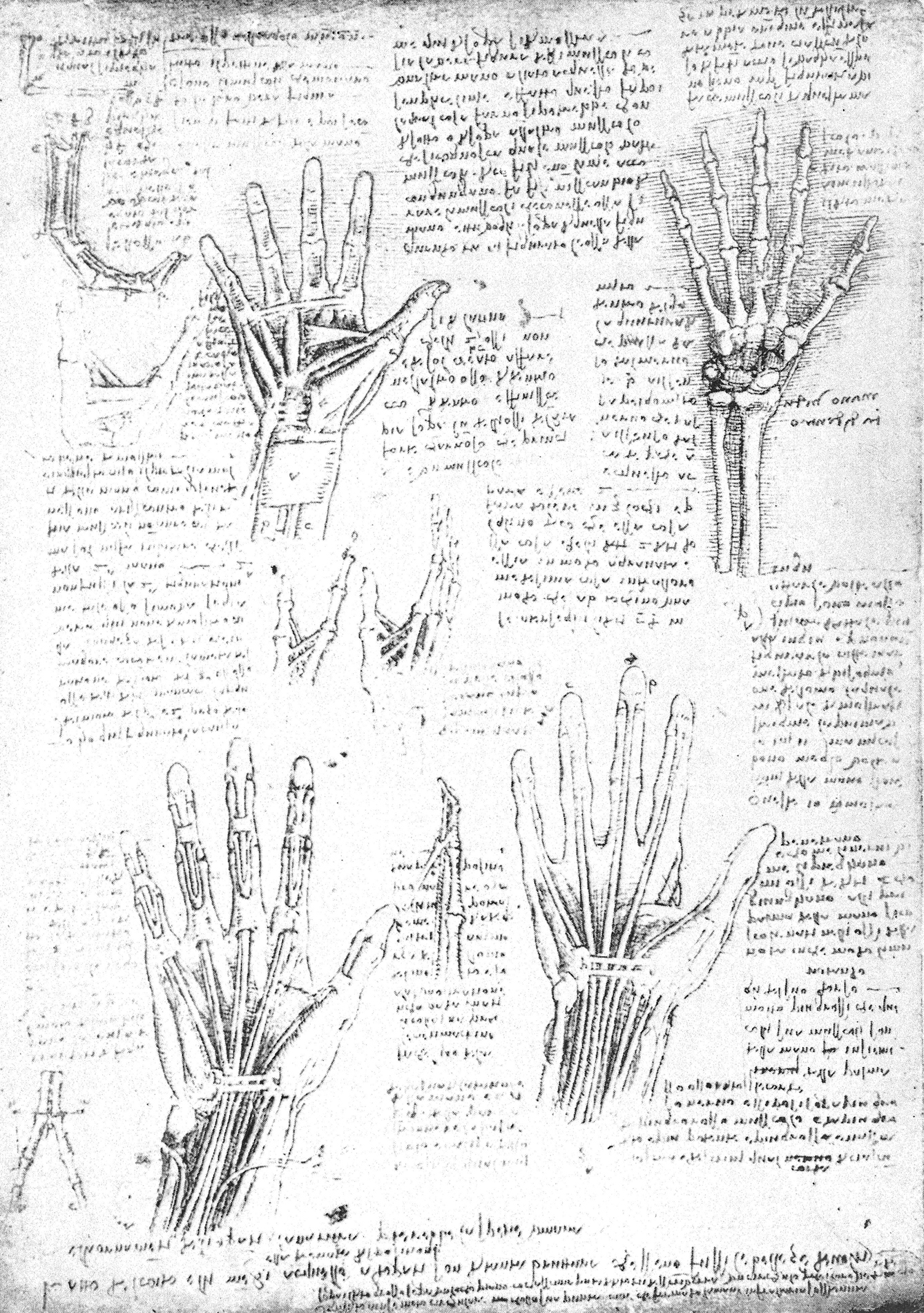

The study of human anatomy flourished in the 16th and 17th centuries, in part prompted by Italian artists wishing to enhance their portrayals of the human figure. Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci are both known to have undertaken anatomical dissections, and their work set a new standard in the portrayal of the human figure.

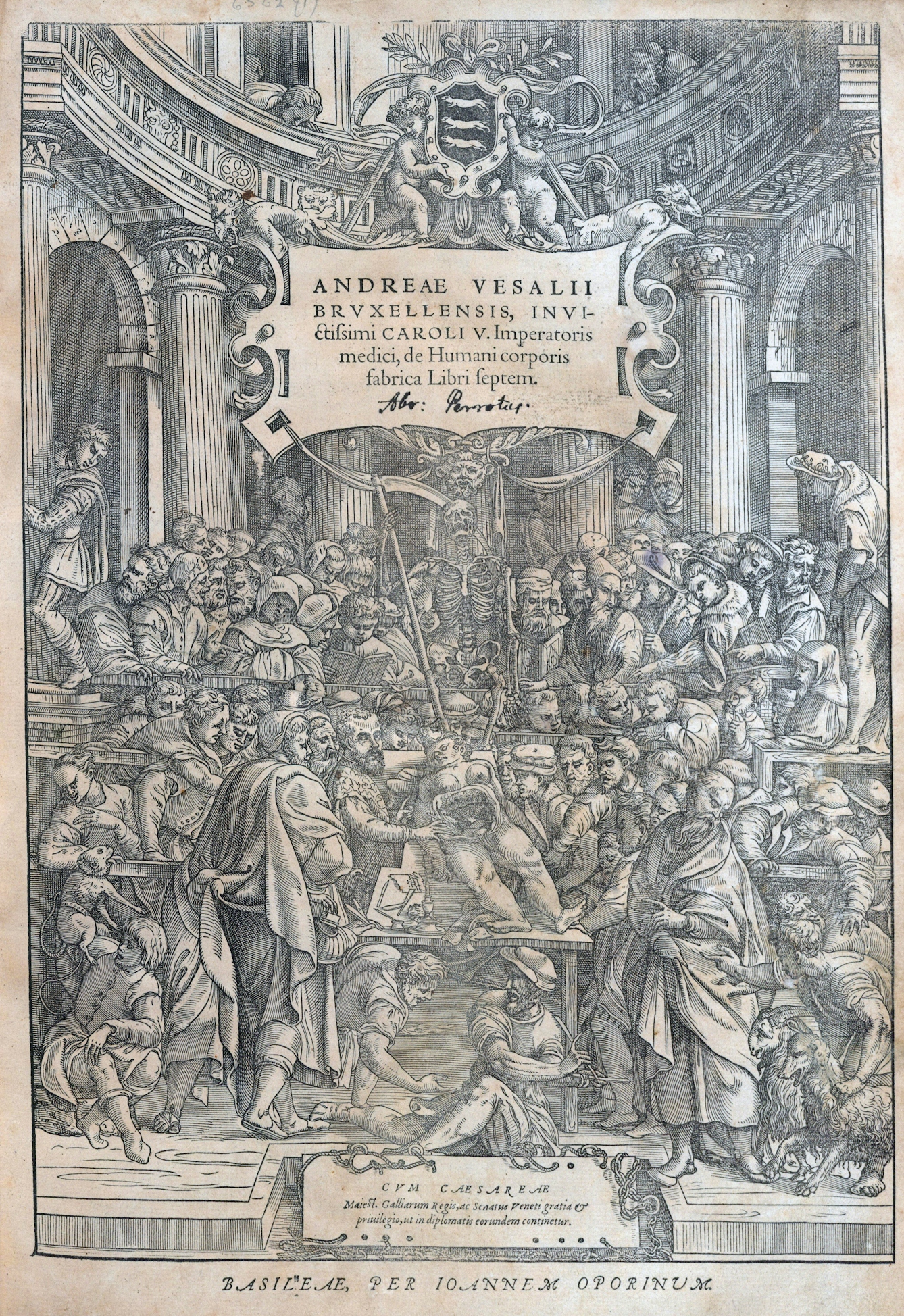

One of the men most closely associated with the understanding the human body was Andreas Vesalius (1514–64), who published what is widely regarded as one of the most influential works of anatomy, ‘De humani coporis fabrica’.

Vesalius argued that anatomy should not be confined to medics but should be studied by all educated Christian men. His influence spread, and dissections, using the bodies of executed criminals, began to be held in public. Ticketholders could watch doctors performing autopsies by candlelight and often with accompanying live music.

By the 18th century, live dissections had become an important part of medical training. As the popularity of these performances boomed, medical students had to compete amongst rowdy crowds to get a good seat, so closed sessions were held in private anatomy schools for medical students only. The proliferation of medical schools created shortages of cadavers, which led to grave-robbing.

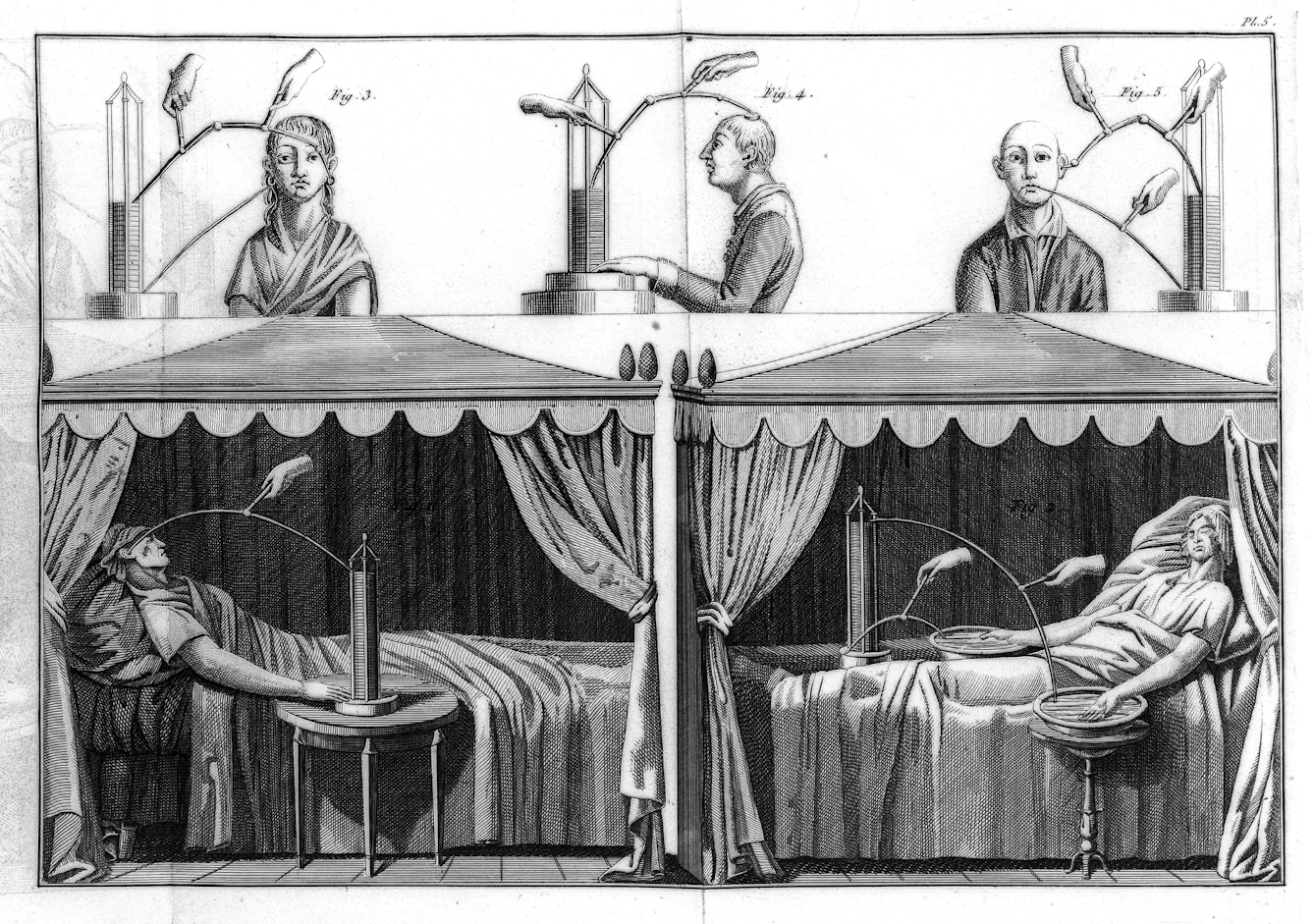

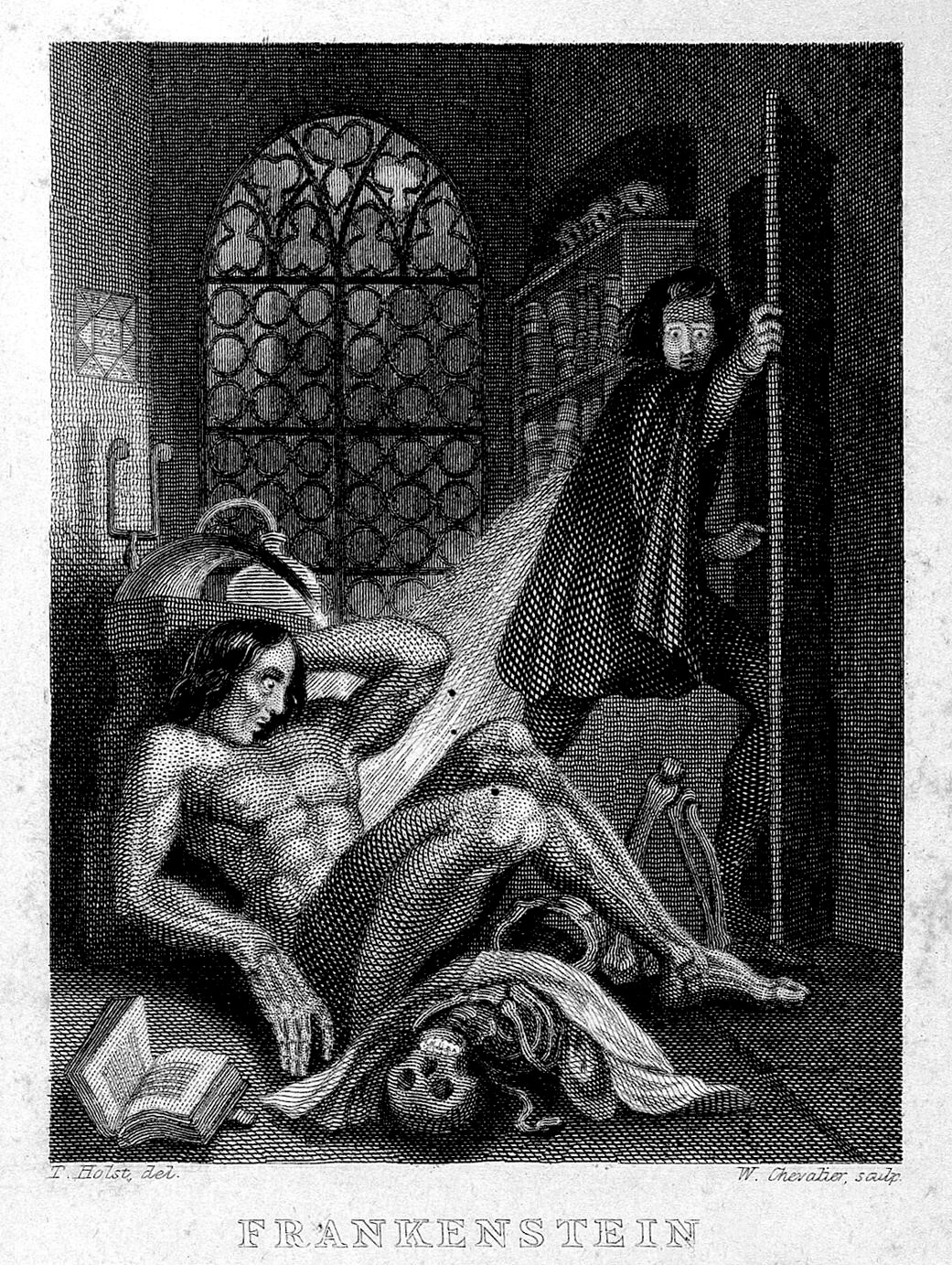

One example of medical theatre that left a lasting impression was the attempt in 1803 by Giovanni Aldini to bring back to life the body of a convicted murderer by charging it with electricity. Astounded onlookers reported that the corpse’s eyes opened, his hand raised and fist clenched, and his legs moved.

Aldini’s ‘act’ provided inspiration for Mary Shelley’s novel ‘Frankenstein’. Shelley would have been familiar with the auditoria of surgery and experimentation, and drew on this as she created her own fictional scientist and surgeon.

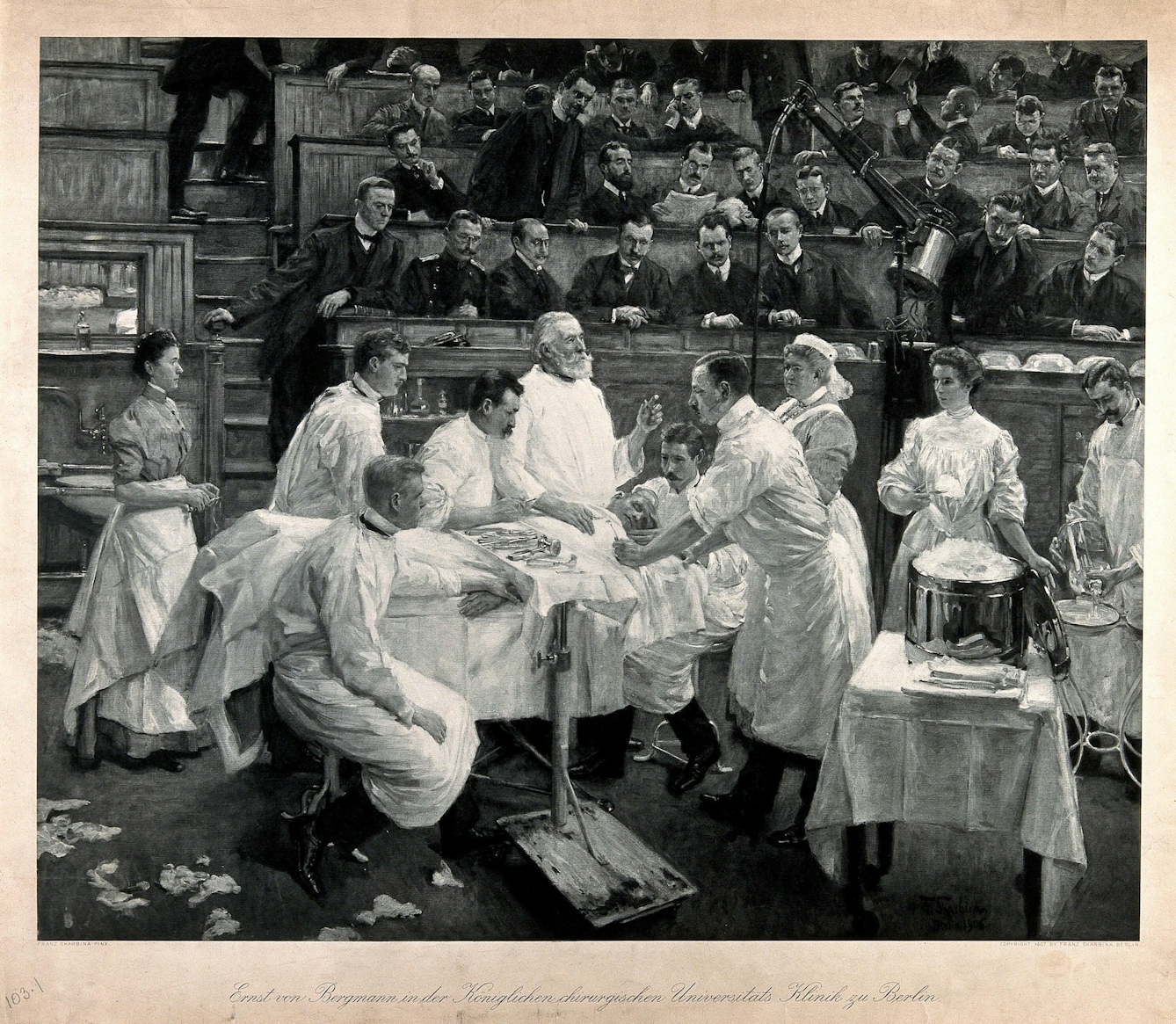

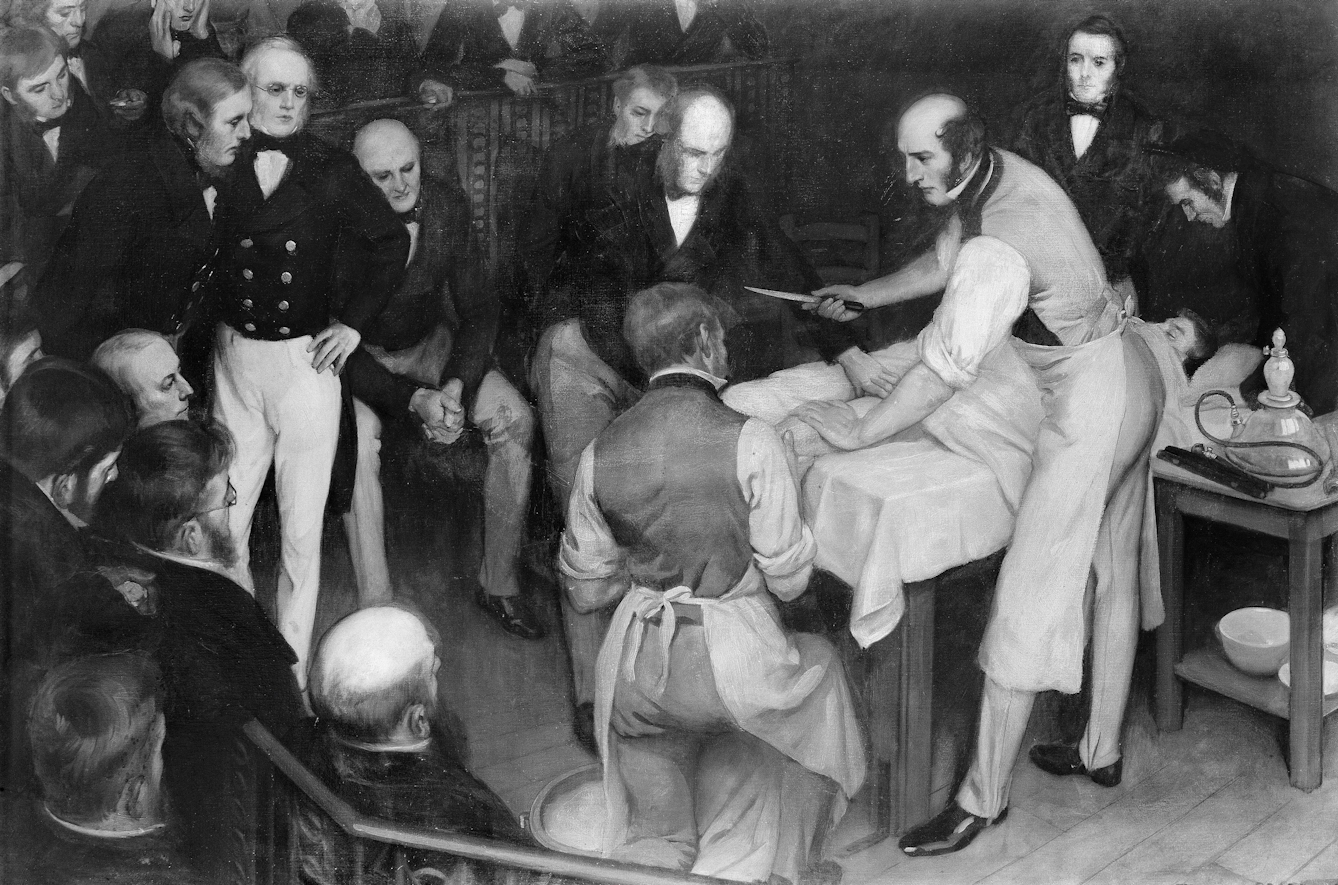

By the early 19th century, surgery on live patients, such as amputations, also began taking place in front of a live audience. The design of the hospital operating theatre was indeed theatrical and the audience view was considered: surgical theatres were based on the anatomical theatres where corpses were dissected to demonstrate and teach anatomy.

As surgical theatre burgeoned, the influence of the stage began to infiltrate the medical world. The operating theatre of Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia was known as the ‘pit’, like the area in which orchestral musicians performed. Surgical theatre made showmen out of surgeons like Scotsman Robert Liston. He was celebrated for his speedy amputations and was reputed to have operated with a knife clutched between his teeth.

For a long time, the woman being cut open on the table would have been the only woman in the operating theatre. Many male medics were horrified by the idea of women witnessing surgery, and one even argued that it would “change their very nature”. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson is probably the first woman in Britain to have experienced an operation as a future surgeon, in 1860; her fellow (male) medical students moved aside to give her a better view. She went on to establish a hospital entirely staffed by women.

By the beginning of the 20th century, operating theatres with audiences had all but disappeared, for two main reasons. The introduction of anaesthetics and subsequent realisation that speed was not of the essence reduced the drama of the spectacle. But more importantly, doctors now understood that spectators brought with them germs and put patients at risk of deadly post-surgical infection.

The days of the old-style operating theatre were numbered as they were replaced by the scientific, sterile and secluded rooms that we think of today.

About the author

Lizzie Enfield

Lizzie Enfield is a journalist and regular contributor to national newspapers, magazines and radio. She has written five novels, and had her short stories broadcast on BBC Radio 4.