From 19th-century croquet-ball representations of molecules to the double helix structure ubiquitous today, images have always been central to our understanding of science. Charlotte Sleigh explores the reciprocal roles of imagery and scientific innovation in visualising new discoveries.

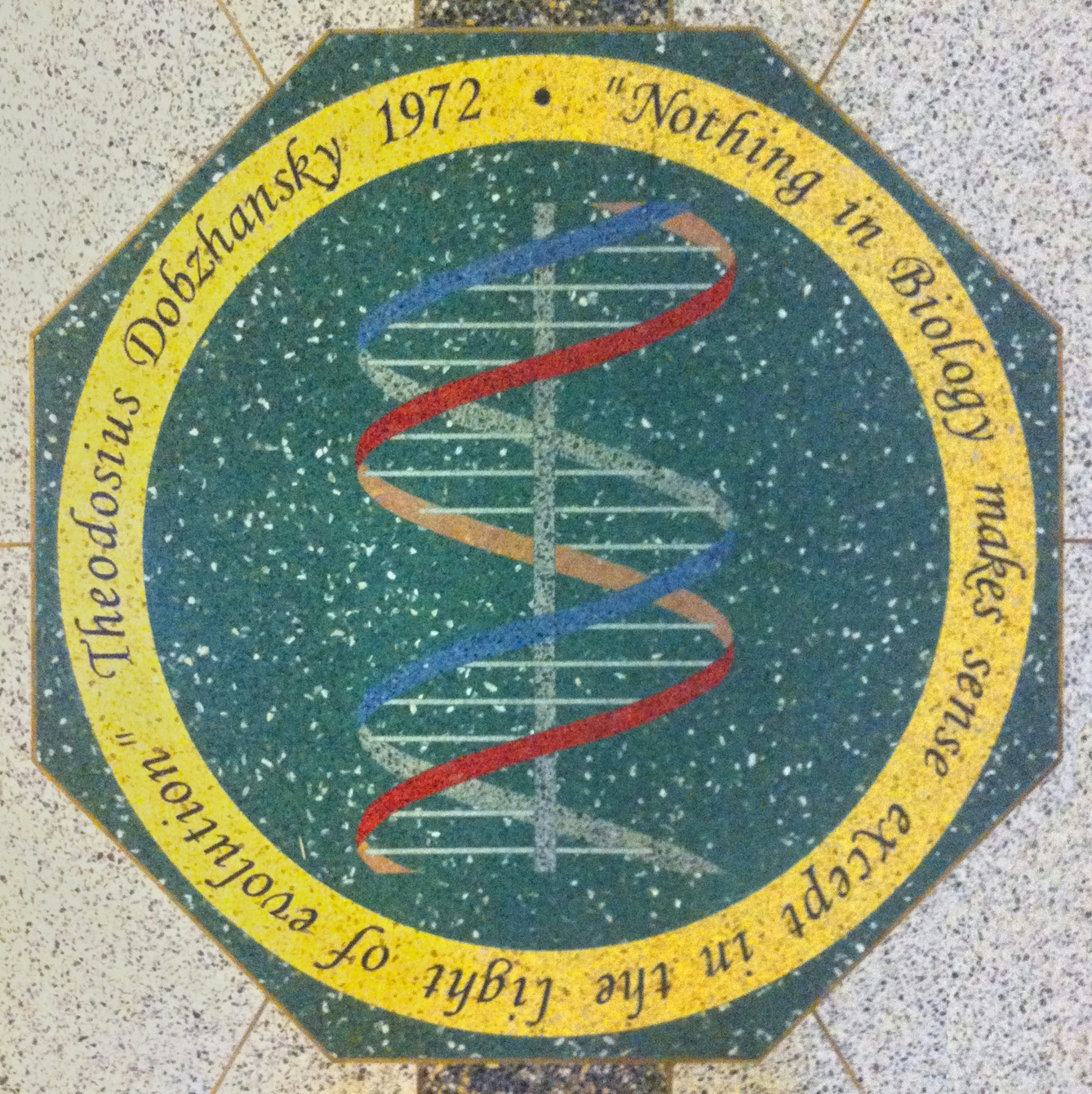

DNA is everywhere. Twisting and snaking across screens, newspaper articles and advertisements, the double helix of DNA is an icon of our age. Often rendered in fluorescent tones or primary colours, it conjures up the mysteries of genetics, and guarantees that a product or a news story represents Science with a capital ‘S’. In this plaque commemorating evolutionist Theodosius Dobzhansky, the helical image of DNA is used to underwrite his scientific status, although his research on the inheritance of chromosomes had no connection with their chemical structure.

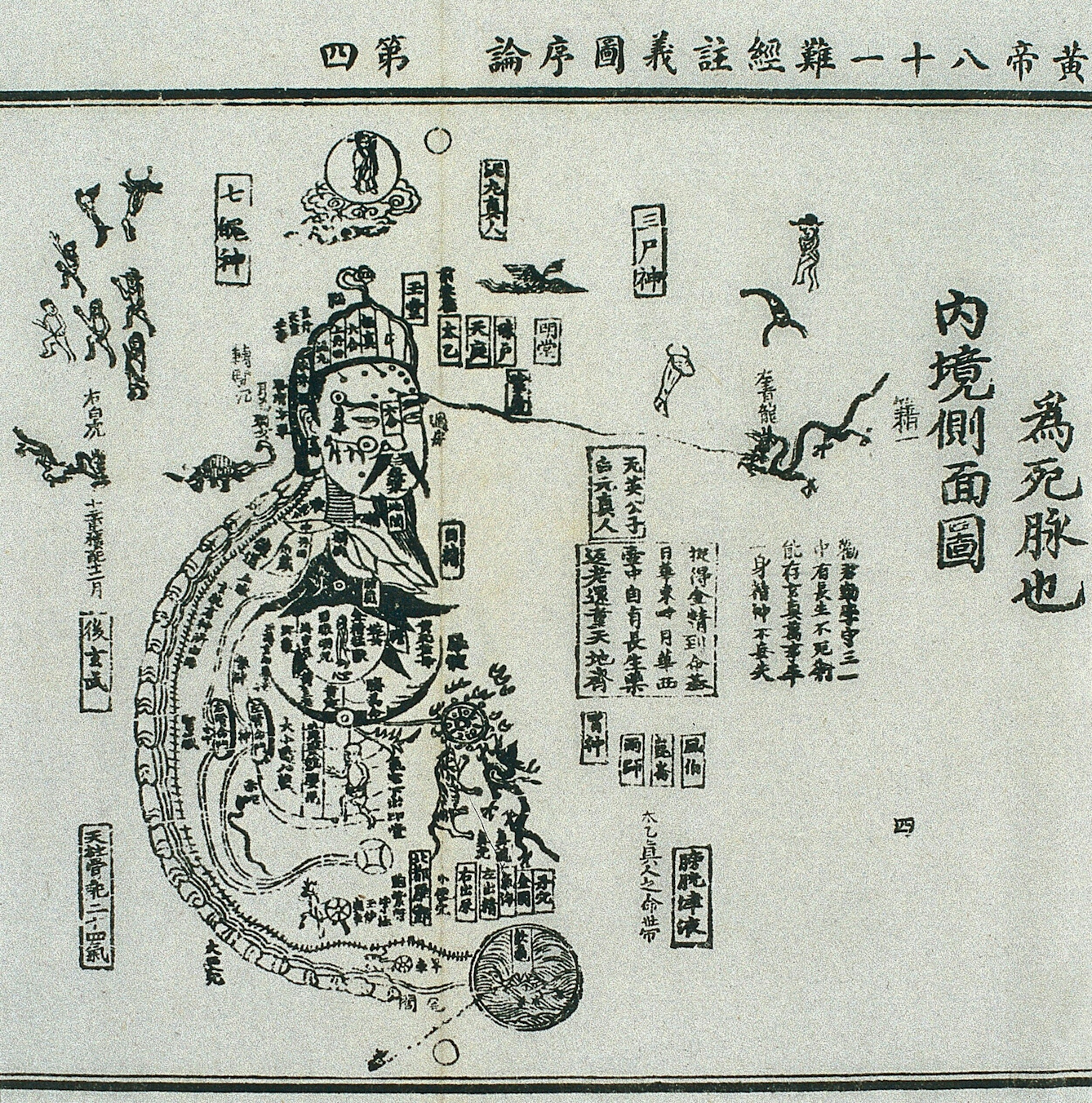

For centuries, doctors and philosophers have tried to visualise the essence of humanity. When we look into our bodies, we see blood, organs and bones, but what are we really made of? In this 15th-century Daoist image, a gentleman is advised to “grasp the golden essence” within his body and “go to the root of life”. During the same period in Europe, alchemical and astrological images were used to visualise the essential nature and make-up of the human body.

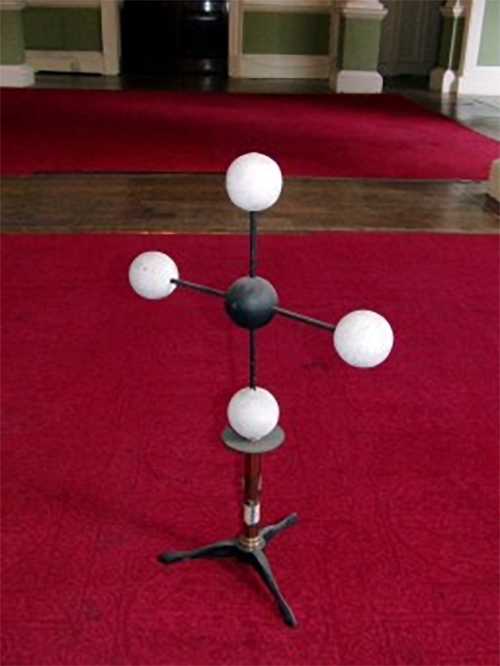

During the 17th century in Europe, the idea emerged that human bodies (and indeed all other materials) could be reduced to small, discrete lumps of matter sometimes known as ‘corpuscles’. In the 1860s, superstar German chemist August Wilhelm von Hofmann wired together balls from the English game of croquet to indicate how atoms of different elements could each combine in different numbers, creating the now familiar ball-and-stick model of molecules. Very few people looking at a ball-and-stick image of DNA would be able to tell you what atoms its blobs represent. But having such a model confirms our faith that biology is based on chemistry.

In the 20th century, modernist philosophy began to explore the possibility that art need not portray ‘real’ things but instead could construct new realities out of language or images. Alexander Calder’s mobiles, made from the 1930s onwards, show modern art following philosophy; many of them bear a striking visual resemblance to ball-and-stick models of chemistry. They hint at a confidence in the power of human beings to construct new realities through science and technology, no longer confined to thinking of nature in ways that rely upon traditional forms of looking and representing.

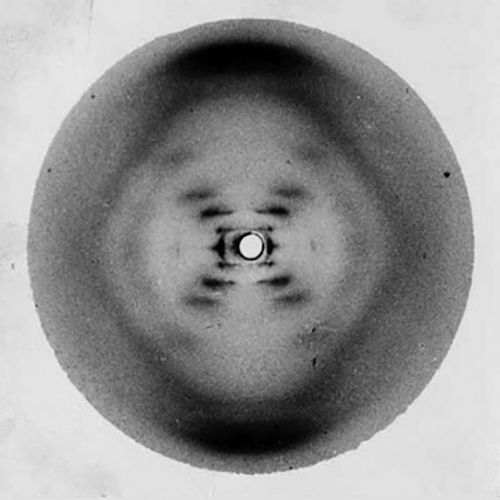

‘Photo 51’, an X-ray diffraction image of a DNA fibre, taken in 1952, is what students of visual culture call an ‘indexical’ sign. Its appearance (a murky X shape) is caused by, rather than looking like, the thing that it represents (the helical structure of DNA). To ‘see’ the helices, DNA must be first be crystallised and X-rays shone through it – like light through a Calder mobile – before being interpreted for its underlying chemical meaning. Both this image and its interpreter, Rosalind Franklin, were neglected until the determined efforts of feminists to restore them to their rightful place in history. The unreadability of the image, and the invisibility of its female creator, seem somehow linked.

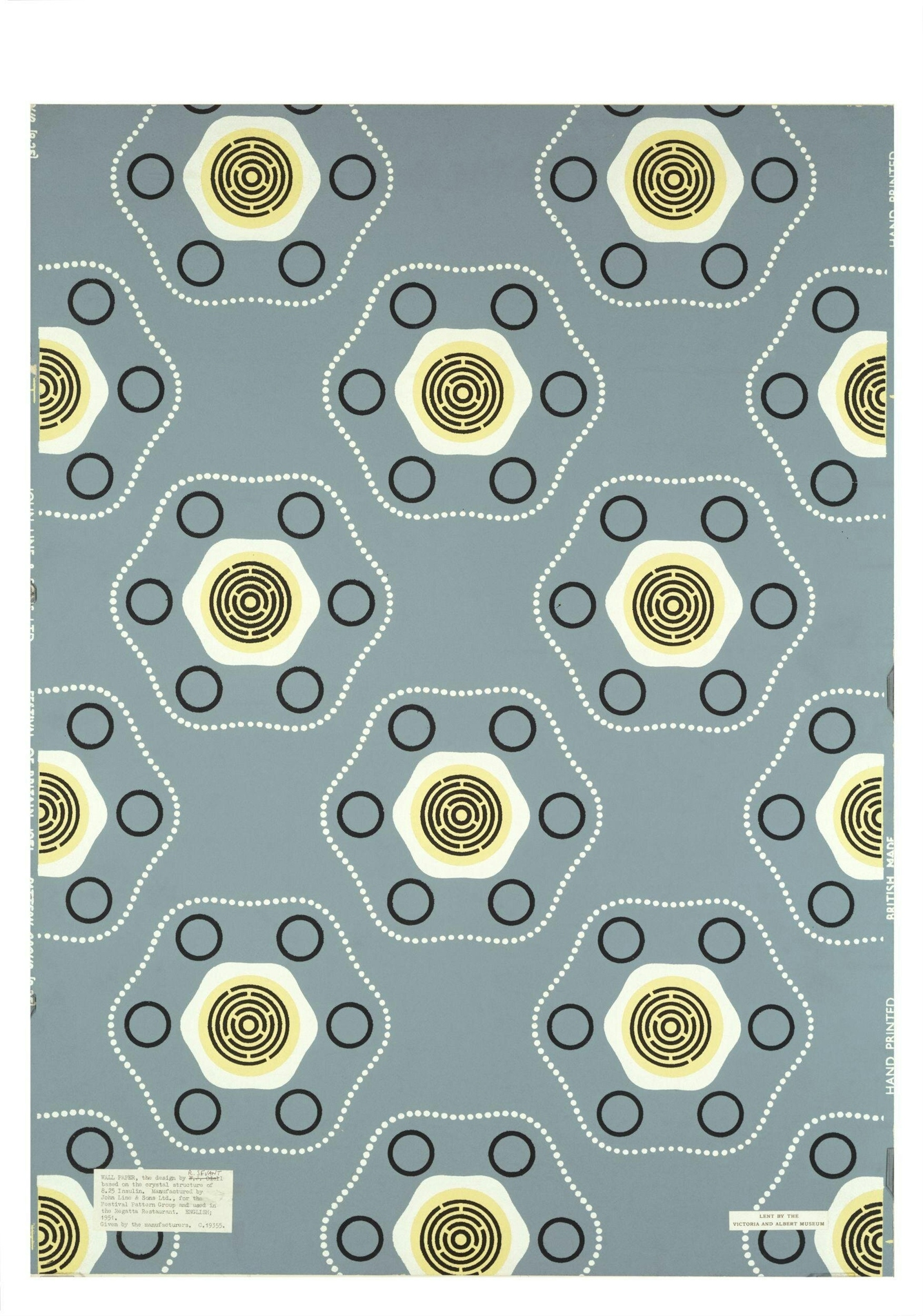

X-ray crystallography was applied to a whole range of complex molecules, both natural and human-made, in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The images created were turned into fabric, wallpaper, and lace designs for the Festival of Britain (1951), lending an optimistic and modernist slant to cultural aesthetics. Human legs, and the nylon that encased them, were equally within the grasp of science. Millions of visitors to the festival were primed to recognise, and celebrate, the great achievement that British science was about to deliver using this visualisation technique.

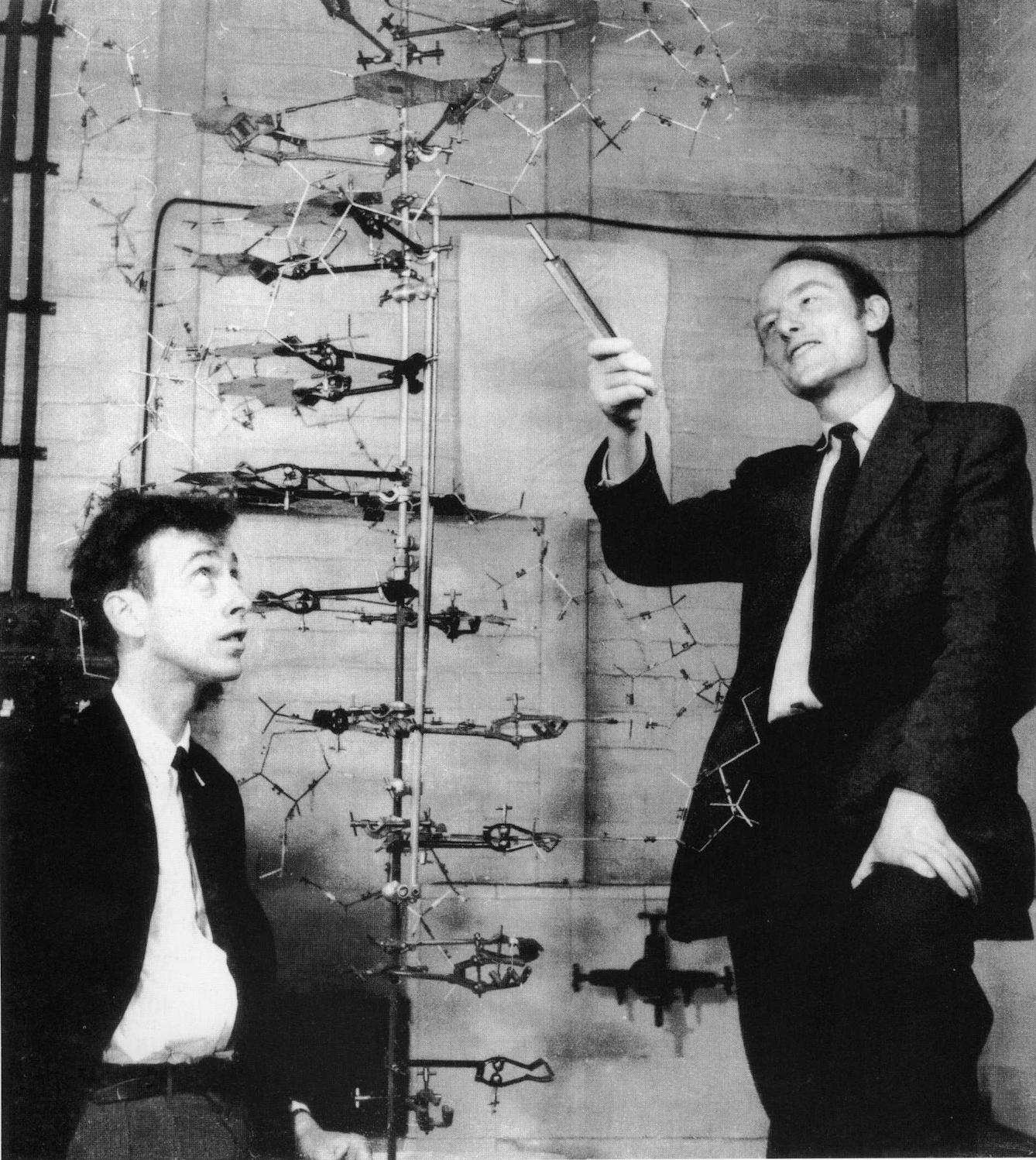

Two years after the Festival of Britain had revelled in the technological aesthetics of chemical molecules, and a couple of months after the structure of DNA was published by Francis Crick and James Watson, this photograph was taken by Antony Barrington Brown for an article in Time magazine. The article was never published, but this photograph from Barrington Brown’s reel has been picked for publication many times since. Watson’s dishevelled, boyish pose, and Crick’s youthful but teacherly air render them not as stuffy old boffins but as eager students of nature. They are representatives of Britain’s scientific, meritocratic future.

Crick and Watson’s upward-spiralling ladder gestures towards a sacred iconography. DNA ascends in ladder form; in the Book of Genesis, Jacob dreams of a ladder reaching to heaven. Barrington Brown’s ladder breaks the frame of the picture just as Christ does in this Renaissance portrayal of his ascension to heaven, with all but his feet disappearing out of view. Crick and Watson’s DNA offers just a fleeting glimpse of the future extent of scientific knowledge. The pair’s skyward gaze suggests that knowledge is leading its young students to higher realms.

Crick and Watson’s model has something of the air of a Meccano model about it. Since the early 20th century, this bolt-together toy has been a gateway to adult participation in science and technology. Crick and Watson’s model spoke to Meccano types, suggesting that molecular biology and biochemistry too were apt fields for the tinkerer or the ‘geek’. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that Meccano fans have turned their skills to modelling DNA. In this example, as in many other visual representations, the identity of the atoms and nucleic acids begins to fade away, the attention placed upon the spiral itself.

Drawings and animations of DNA show the twin helixes ‘unzipping’ from each other, ready to reproduce. The zip, a modern and convenient mode of fastening and unfastening, was developed in the early 20th century. Novelist Erica Jong used the phrase “zipless fuck” to describe an uncomplicated sexual encounter – no fumbling to remove one’s clothes, no guilt or anxiety about pregnancy. With the growth of contraception, the biology of reproduction could be separated from the pleasure of sex. Babies, in turn, could be created without sex, through IVF: not a DNA manipulation in itself, but closely connected in the popular imagination with the “designer baby”. DNA unzips so that humans don’t have to.

This helical bottle of ‘DNA’ perfume from 1993 summons DNA as the essence of the self, now discoverable via mail-order ancestry-testing kits (though not quite at the time the perfume was produced). In an era of genetic medicine, DNA also represents the notion of science specially tailored to the individual. This example reduces the visual icon to the very faintest connection with the original. Only the helices remain, and they are coiled in parallel, rather than – as Crick, Franklin and Watson discovered – antiparallel. Like many images of DNA, it pays no attention to the direction of twist, which has scientific importance for the direction in which the molecule is read. The image of DNA has been almost emptied of the science of DNA as it has entered the visual lexicon.

About the author

Charlotte Sleigh

Charlotte Sleigh is an interdisciplinary writer and practitioner in the science humanities. Her most recent book is ‘Human’ (Reaktion, 2020). She is Honorary Professor at the Department of Science and Technology Studies, UCL, and current president of the British Society for the History of Science.