In the 1950s, doctors began to use a painful and distressing ‘therapy’ to ‘cure’ people of being gay, at the time classified as a mental health disorder. With testimony from those who’ve experienced it, neurologist Jules Montague charts the history of conversion therapy, still legal today in many countries around the world.

Jeremy Gavins was 14 years old when he fell in love with Stephen. “He looked like the singer Donovan, a younger version,” Jeremy tells me. “Black curly hair, a nice kissable nose as well. I was the rough, chunky, rugby-playing type and he was arty, slim, more delicate.”

Now aged 67, Jeremy lives in Ulverston, some 70 miles from his childhood home in Keighley. His rescue dog Timmy (“part collie, part fox”) sits at his feet. Next to the wood burner on its stone hearth is a pile of notebooks filled with details of the drystone walls he has built for decades. On his black T-shirt are Snoopy and ‘Peanuts’: “In a world where you can be anything, be kind.”

He and Stephen were friends to begin with, but two years later, Jeremy told him: “I think you are the most beautiful boy in the world. I love you.” Stephen felt the same way. Realising they would be going to different universities in different towns was devastating.

A teacher found Jeremy collapsed and crying alone in the corridor. Jeremy explained he was in love with Stephen. The headmaster told Jeremy, then aged 18, that homosexuality was a terrible affliction. Jeremy was sent to a psychiatrist, who decided that treatment was needed urgently.

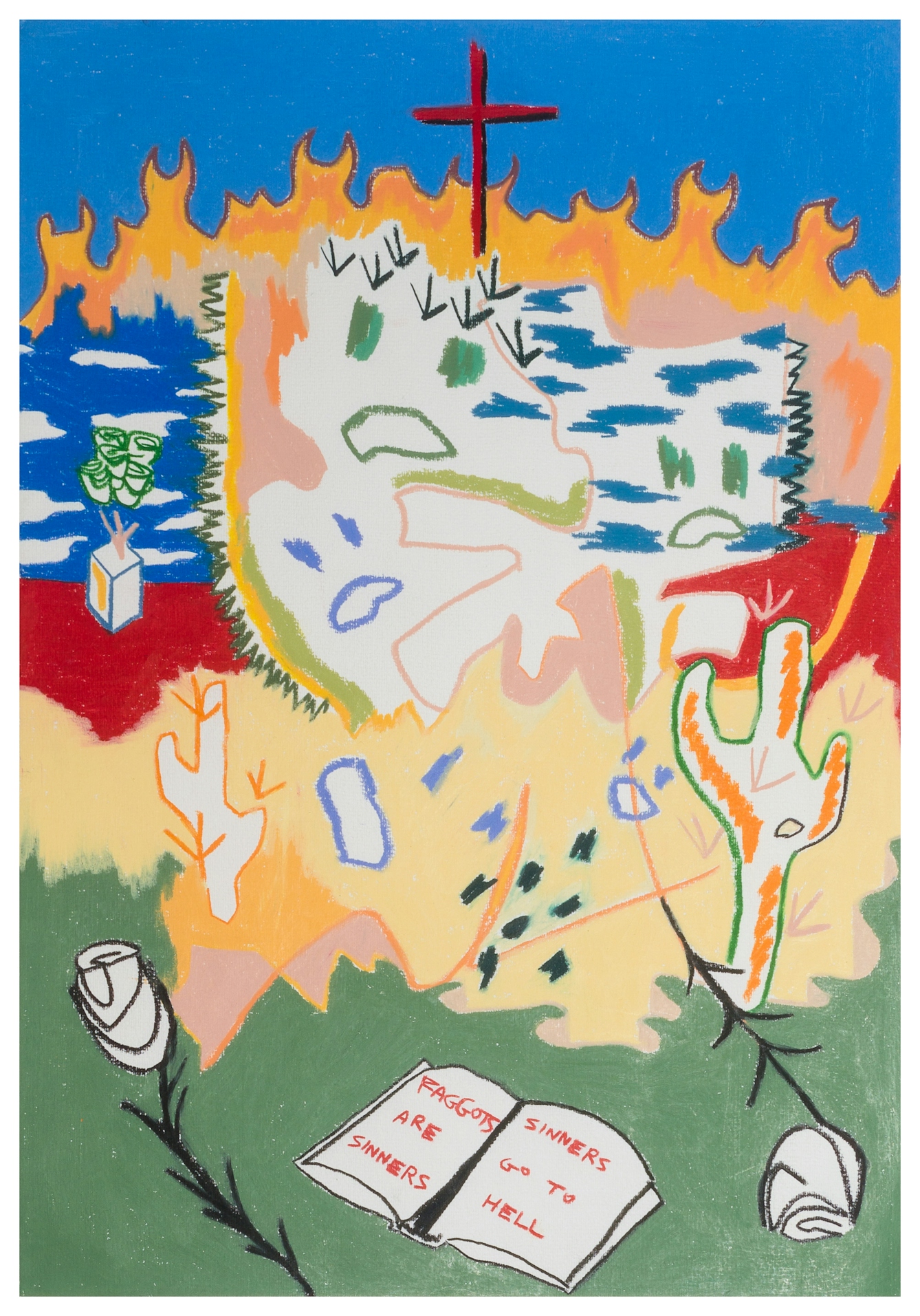

‘Faggots are sinners and sinners go to hell’, 2016. Stephen Nestor Ostrowski.

Within days, a priest walked Jeremy to Lynfield Mount Hospital. There, he had to sit in a wooden chair with a straight back and arms. His wrists were fastened down with leather straps. A grey band was attached to his right forearm, and the band’s electric wires were connected to a box on a table in front of him.

Jeremy was shown pictures of men and women, most of them naked. Electric shocks accompanied each picture of a naked man, but not the pictures of the women. With each jolt, Jeremy’s arm would contort, his body would spasm. He was there for an hour and 20 minutes. Weekly sessions followed for months.

The psychiatrists and psychologists who conducted aversion therapy like this claimed that it would turn patients away from their homosexuality by inextricably connecting it in their minds with emotional trauma and physical pain. As I learned from Jeremy, this treatment left a devastating legacy. It also paved the way for the “conversion therapy” that exists today.

Drugs and electric shocks

Extensive use of aversion therapy was first made in Prague in the 1950s by the psychiatrist and sexologist Kurt Freund, whose publications reached a global readership. This therapy was enabled far beyond Prague by the designation of homosexuality as a “mental disorder” in diagnostic manuals. In the UK a 1955 British Medical Association committee report asserted that “some [male] homosexuals appear to be incorrigible offenders, often inveterate and degenerate sodomists and debauchers of youth”.

The committee proposed experimental treatment centres where ‘inmates’ should follow a routine of work, exercise and study, with strict discipline and supervision. One Bristol doctor who conducted aversion therapy wrote that he had been spurred on by the BMA report, which had “laid stress on the need for research into the treatment of homosexuals”.

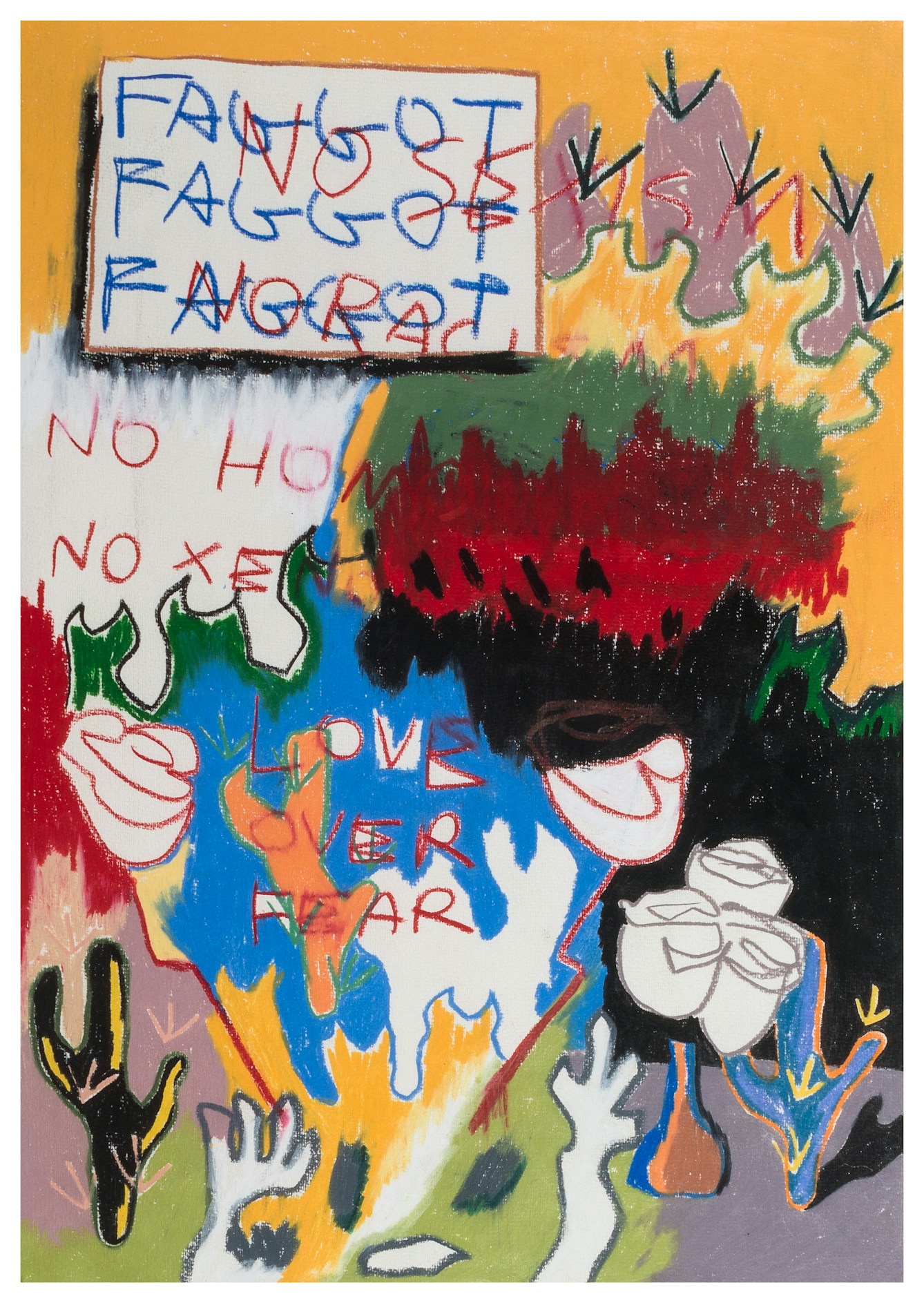

‘If words are “just words”, why do they burn?’, 2016. Stephen Nestor Ostrowski.

At least several hundred men in the UK were subjected to aversion therapy. There were treatment hubs in Glasgow, Surrey, Manchester and Birmingham, as well as individual researchers using the technique in London, Leicester, Barrow Gurney (near Bristol), Lancashire and Belfast. The Observer published an article titled ‘How doctor cured a homosexual’ and the Sunday Pictorial’s piece was headlined ‘“Twilight” men – now they can be cured’.

Although aversion therapy as Jeremy experienced it had largely become a thing of the past, “gay conversion therapy” continues to be practised internationally.

The devastating effects were not reported. At the Maudsley, a psychiatric hospital in south London, the psychiatrist John Bancroft employed an electric-shock technique similar to that used on Jeremy. According to Bancroft, the most successful treatment was on a 37-year-old zoologist. Two and a half years after his 35 sessions – each session lasting up to 90 minutes with a minimum of 60 shocks per session – he held a “phobic anxiety to potentially attractive males”, and tried to kill himself when a male friend became engaged to a woman.

During a six-month relationship with a woman, “he had a constant fear of impotence which prevented him from attempting genital contact”. Some patients, Bancroft wrote, “developed impotence in both homosexual and heterosexual encounters, eventually rejecting relationships entirely”.

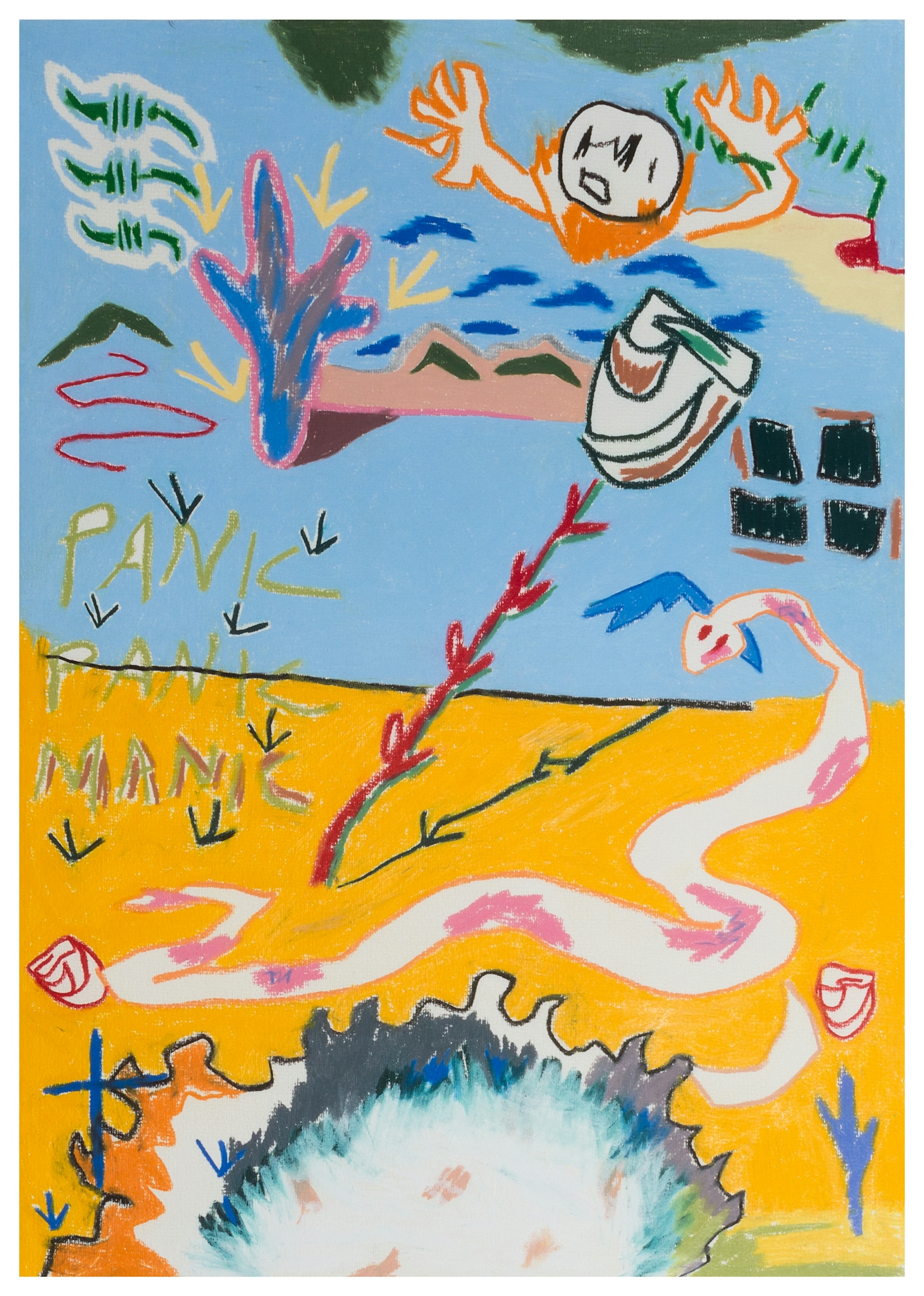

‘How close is too close?’, 2016. Stephen Nestor Ostrowski.

Homosexuality no longer a ‘disorder’

By the time Jeremy was 25, he had also stepped away from relationships and sex. He tried to kill himself many times, and led a peripatetic life marked by depression and anxiety, by alcohol dependence and agonising chronic pain.

With time, aversion therapy faded as an international movement of psychiatric survivors and persuasive mental health experts, bolstered by shifting legal frameworks and human rights legislation, managed to get homosexuality removed from diagnostic manuals as a mental health disorder.

Although aversion therapy as Jeremy experienced it had largely become a thing of the past, “gay conversion therapy” continues to be practised internationally. In the main, the electric shocks and drugs of aversion therapy have been supplanted by the tools of conversion therapy: prayer, talk therapy, hypnosis and exorcism.

In the UK, only a partial ban on conversion therapy exists – transgender people are still excluded from protection, though new legislation is promised to include gender orientation in legal protection against the practice. Two per cent of respondents to a 2017 survey of more than 100,000 people who identify as LGBTQ+ had undergone conversion therapy and five per cent had been offered it. Extensive research proves these methods cause enduring mental health problems, including depression and suicidality, as well as internalised homophobia.

Untitled (Sarah), 2017. Stephen Nestor Ostrowski.

An important apology

In 1990, Sarah Carr had experienced mental distress in her first year of university: “I’d been unwell, and I thought I shouldn’t be cutting myself and I shouldn’t have tried to kill myself. So maybe I should get some kind of help.” Her psychologist decided that Sarah’s sexual orientation was to blame, and conducted involuntary “reparative psychotherapy”.

“He wanted to try to coax me into a state of at least bisexuality, and as part of that he showed me pornographic pictures [of women] intended for heterosexual men, and asked me if I found them attractive or appealing or if they turned me on. I was, like, ‘No, they don’t,’ and he said, ‘Let’s try and reinforce that [negative] feeling through hypnotherapy.’”

The therapist then decided something traumatic had marked Sarah’s past, hypnotising her to bring forward “repressed memories”. At this point, Sarah absconded. It took years to find a psychologist she could trust. She re-established a relationship with her parents and became an academic in the realm of mental health policy.

One strand of her research examines the mental health of lesbian, gay and bisexual people. Her archival discoveries offered important moments of recognition. “There’s an association with being gay and being socially isolated, but I felt kind of historically isolated. I hesitate to use the word ‘therapeutic’, but it was quite therapeutic going on that journey to meet them.”

Conversion practices have been widely condemned by medical organisations. Nevertheless, research from influential medics has been leveraged by proponents of conversion practices. Robert Spitzer, known by some as the father of modern psychiatry, was instrumental removing the diagnosis of homosexuality from diagnostic manuals.

‘Break the chains that bind (wild at heart)’, 2016. Stephen Nestor Ostrowski.

But in an ill-conceived 2003 study, he concluded that conversion therapy changed sexual orientation in the majority of participants. Social conservatives waved the study’s findings about in a victory lap for reparative therapy. But the research had been deeply flawed, and included responses from politically active ‘ex-gay’ advocates. In 2012, as his health was failing due to Parkinson’s disease, he asked for the study to be retracted: “I believe I owe the gay community an apology,” he wrote.

Time and therapy

To this day, instead of slippers, Jeremy wears old walking boots with their laces undone. He cannot wear a watch or a shirt with buttoned cuffs: both remind him of the straps the man in the white coat used to tie him down.

Time and therapy have helped him to make sense of his journey. “Five years ago, if I had this conversation, I’d be into my 15th hanky with tears, but I can talk about it now, I understand it.” Catharsis has come in writing and speaking about his experiences. “Everybody knows I’m gay, I’ve come out to my clients, all the farmers. They just think I’m a nice fella.”

He later discovered that Stephen had died tragically in a road accident, but if the aversion therapy was supposed to banish the boy he adored from his mind, it certainly did not work. “Back then, I found a picture in a magazine that looked a little bit like him, and on the picture I wrote, ‘No matter what they do to me, I will always love you.’ Even now, I love Stephen,” he says. “It’s ridiculous, isn’t it? I’ll never stop loving him.”

About Jeremy Gavins

Jeremy Gavins’ memoir, ‘Is it About That Boy? The Shocking Trauma of Aversion Therapy’ tells the story of his life before aversion therapy and how, after nearly forty years, he recovered from the experience.

About the artwork

Stephen Nestor Ostrowski was raised as an expatriate primarily in Bangkok, Thailand among an evangelical missionary community and was subjected to conversion therapy as a teenager. Now an artist living in the New York, they discuss conversion therapy as a facet of their work, its impact as trauma, and the importance of finding ways to manifest the truth, including showing a selection from this body of work as ‘side effects include: hope, nausea’ at Spring/Break New York, 2018. Subsequently, they were an individual grant recipient for Painting/Drawing from the Peter S Reed Foundation in 2019.

This work is a conscious metaphor for the feeling of veering into an unknown fate. Pointing to omnipresence, and the implication of enduring friction. In Ostrowski’s experience, it is something that feels geographic and vast. To acknowledge the maddening incongruities – the side effects. To reference a dichotomy between sensations – hope and nausea. Displayed to lay bare the impact of dangerous constructs that befall us.

About the contributors

Jules Montague

Doctor Jules Montague is a former consultant neurologist, and the author of ‘The Imaginary Patient: How Diagnosis Gets Us Wrong’ (Granta 2022). It explores how the practice of diagnosis is tainted by the forces of imperialism, politics, discrimination and Big Pharma. She also writes about health and science for the Guardian, the BBC, and New Scientist. Her first book, ‘Lost and Found: Why Losing Our Memories Doesn’t Mean Losing Ourselves’ (Sceptre, 2018), explores what remains of the person when the pieces of their mind go missing.

Stephen Nestor Ostrowski

Stephen Nestor Ostrowski is a American-born artist based in New York. An autodidact primarily working with painting and sculpture, their work touches on consecration, faith, secrecy and exposition, response mechanisms, decomposition, and belonging.