In the 1950s, many psychiatrists thought that homosexuality could be reformed. Czech psychiatrist Kurt Freund found that it couldn’t – and his discoveries led to a change in the law.

Can our sexual desires be transformed?

Charlie WilliamsSarah MarksDaniel Pickaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

Until the 1960s, male homosexuality was illegal in most countries. Ironically, the first European nation to make the radical move towards its active decriminalisation was one of the most repressive regimes of the Eastern bloc at that time: Communist Czechoslovakia. This spectacular policy change in 1961 contradicted years of homophobic Stalinist proclamations prioritising marriage and the traditional nuclear family as the ideal breeding ground for a strong socialist population and the foundation for a thriving national economy.

Kurt Freund’s book ‘Homosexuality in Man’, published in German by Hirzel Verlag in 1963, and a year earlier in Czech by the Czechoslovak State Medical Publisher.

The move towards decriminalisation followed the failure of a large-scale attempt to ‘cure’ male homosexuality once and for all. Czech psychiatrists used a tailored form of ‘aversion therapy’, applying electric shocks or nausea-inducing drugs while showing gay men erotic images of male bodies. They hoped to force their patients to associate homosexuality with pain and disgust and recondition both their behaviour and their personal identity.

Aversion therapy had been developed by psychiatrists to treat alcoholism in America in the late 1930s. By the 1950s, clinicians in both the West and the Communist world began to apply it, experimentally, to a wide range of ‘deviant’ behaviours. This growing faith in behaviour modification was inspired in large part by the work of the Russian Nobel Prize-winning physiologist Ivan Pavlov. His experiments on ‘conditioned reflexes’ in animals showed the degree to which external stimuli could affect the body and behaviour. More than half a century earlier, in the 1890s, he had shown that his laboratory dogs could be made to associate the sound of a buzzer with the promise of food and eventually induced to salivate, whether or not there was actual food present.

Ivan Pavlov and his colleague Maria Petrova conducting conditioned reflex experiments on a laboratory dog.

A generation of psychiatrists and psychologists in the 1950s refined Pavlov’s theories in experiments on human beings. Spectacular claims were made about curing people’s mental health problems through such conditioning. If a dog could learn to associate a sound with food, perhaps an arachnophobe could come to connect spiders with a sensation of relaxation instead of fear – an approach that became known as desensitisation therapy. And if such positive associations could be created, perhaps so too could negative ones.

Pavlov’s ideas were combined with the work of American behaviourist psychologists John Watson and B F Skinner, who argued that reward and punishment also played their part in conditioning. Experimental ‘behaviour therapy’ was used to cancel out a myriad of ‘unwanted’ feelings and actions, from same-sex attraction to fears of flying. Techniques designed to ‘rid’ people of homosexual desire – and even to fully transform them towards heterosexual norms – had become a mainstay of institutionalised psychiatry by the 1950s and 1960s. Some patients referred themselves, hoping to be able to conform to the social norms of the time, and others arrived through the criminal justice system. These techniques also began to replace cruder ‘cures’ for homosexuality, such as the chemical castration inflicted on the mathematician and codebreaker Alan Turing.

Kurt Freund

Measuring desire

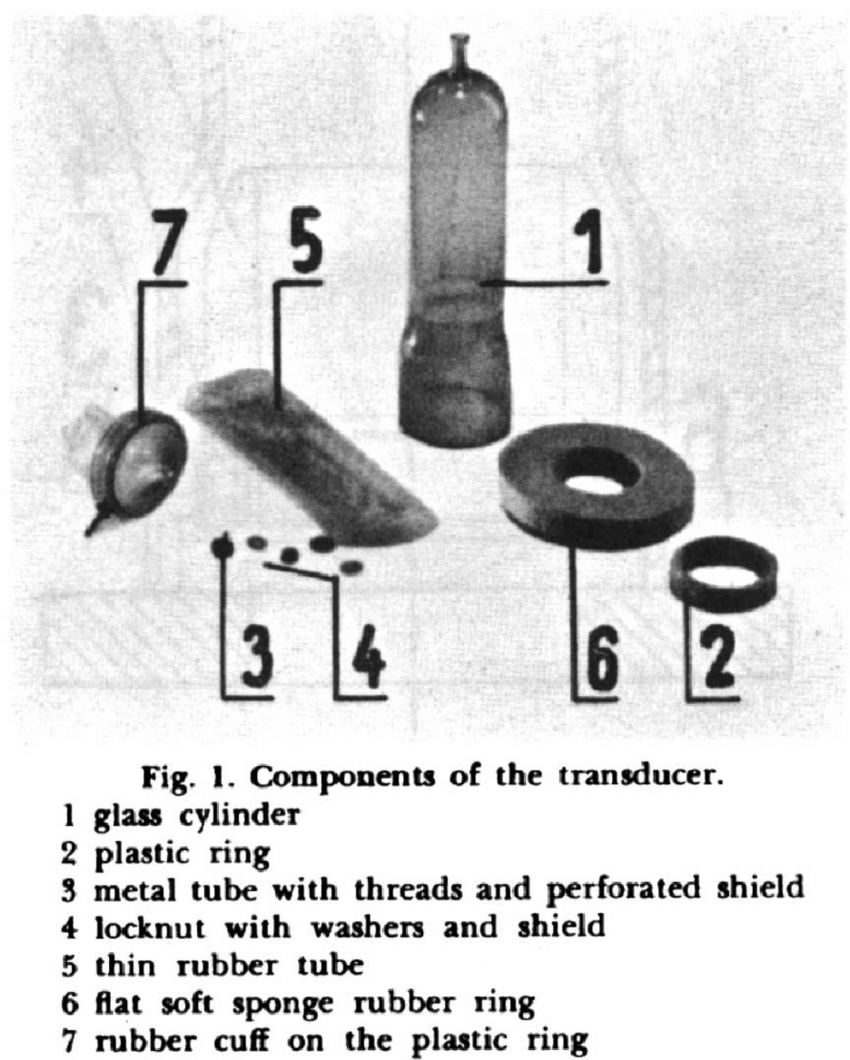

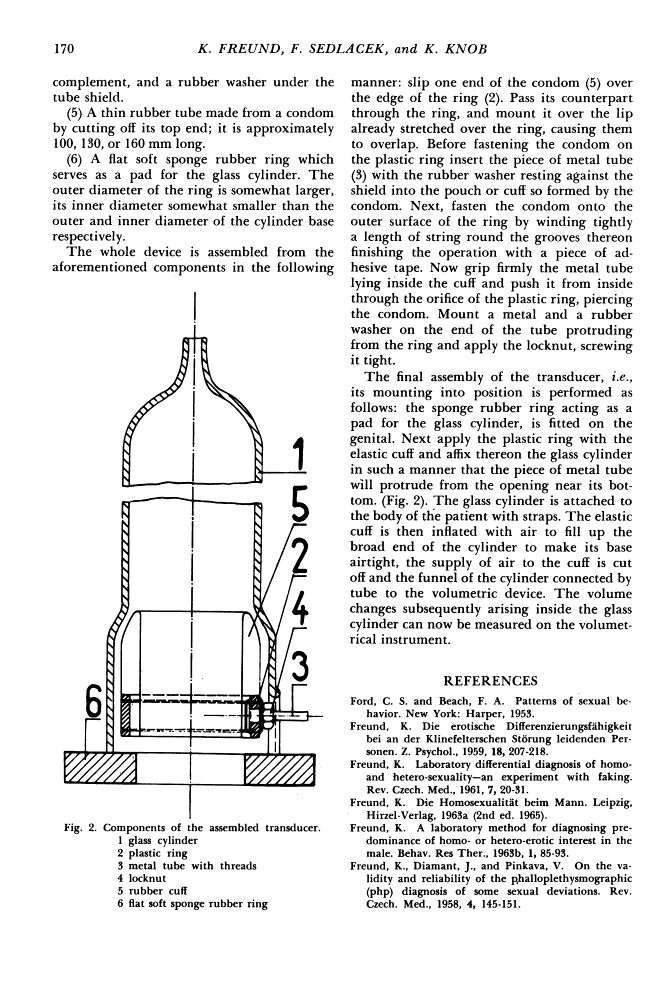

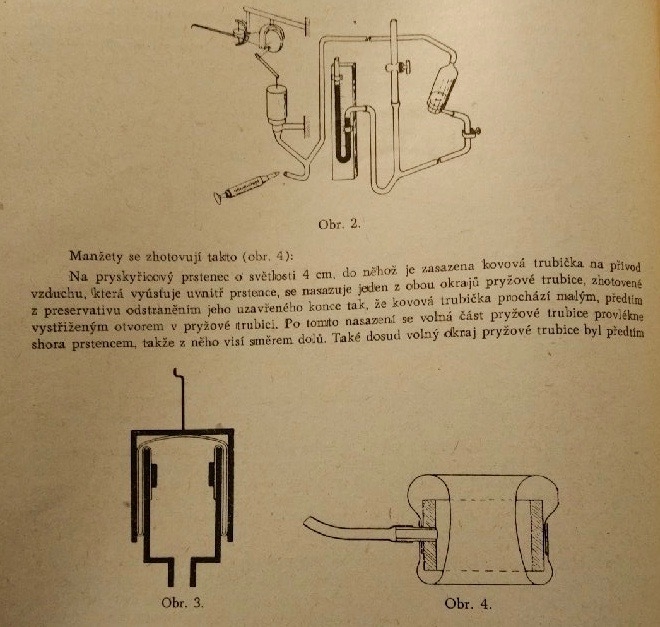

Czech psychiatrist and sexologist Kurt Freund experimented with these behavioural approaches on his homosexual patients, seeking to prove whether the ‘cure’ was effective. Freund was interested in quantifying and categorising the variety of human sexual life; in the 1950s he had invented a device to measure the extent of male arousal: the penile plethysmograph. Through measuring the air pressure within a sealed container enclosed around the subject’s penis, Freund claimed to be able to tell whether they were experiencing sexual arousal.

The penile plethysmograph

An early version of the plethysmograph from Freund’s first publication on his experiments from the Czechoslovak psychiatry journal in 1957, ‘Diagnostics of Homosexuality in Men’.

The plethysmograph apparatus designed by Freund with his colleagues F Sedláček and K Knob.

Details of how the plethysmograph functioned in practice from The Journal of Experimental Analysis of Behaviour, 1965.

The device was a response to a problem posed by Czechoslovak army commanders, concerned that men were attempting to evade military conscription by faking homosexuality. Freund used the plethysmograph as a means of screening: the men’s innermost desires were measured, quantified and recorded in response to a variety of erotic images of men and women. Those who remained unaroused by male bodies were sent off to ‘defend socialism’ in the Czechoslovak People’s Army.

Freund was curious whether his device might be able to tell him more about the enigmas of sexual desire. He began to use it experimentally with patients who had presented themselves because they were attracted to other men, selecting patients who were not under coercion from the authorities. Patients underwent aversion therapy over the course of five days, alternating with testosterone injections to condition positive associations when looking at images of semi-naked women. Could the plethysmograph show, finally, that conditioning could purge men of unwanted desires and replace homoerotic urges with heterosexual ones?

The answer was no. Freund found that the treatments consistently failed to eliminate gay attraction. The plethysmograph showed that no matter how much conditioning the men endured, they were still unequivocally stimulated by erotic pictures of other men. Although a few went on to have successful heterosexual marriages, none of the participants reported a diminution in their attraction to the same sex. Looking at these startling results, Freund abandoned the idea that sexual preference could be altered through psychological intervention. He also lobbied the Central Committee of the Communist Party to change the law. Homosexuality, he argued, could not be ‘cured’ and should not be punished. The law was changed in Czechoslovakia, and Hungary followed suit shortly after.

He wasn’t alone. In the 1960s, socialist countries in Eastern Europe were moving away from the dogmatic decrees of the Stalinist ideology that had dominated the 1950s. Scientific expertise was being given more credence; there was a new, utopian vision that findings from science and technology could revolutionise society and improve its governance, albeit still along Marxist lines. In her book, ‘Sexual Liberation, Socialist Style’, Kateřina Lišková tells us that while the family itself remained of central importance to the nation, sexual liberation was a feature of social transformations in Communist Europe as well as in the West.

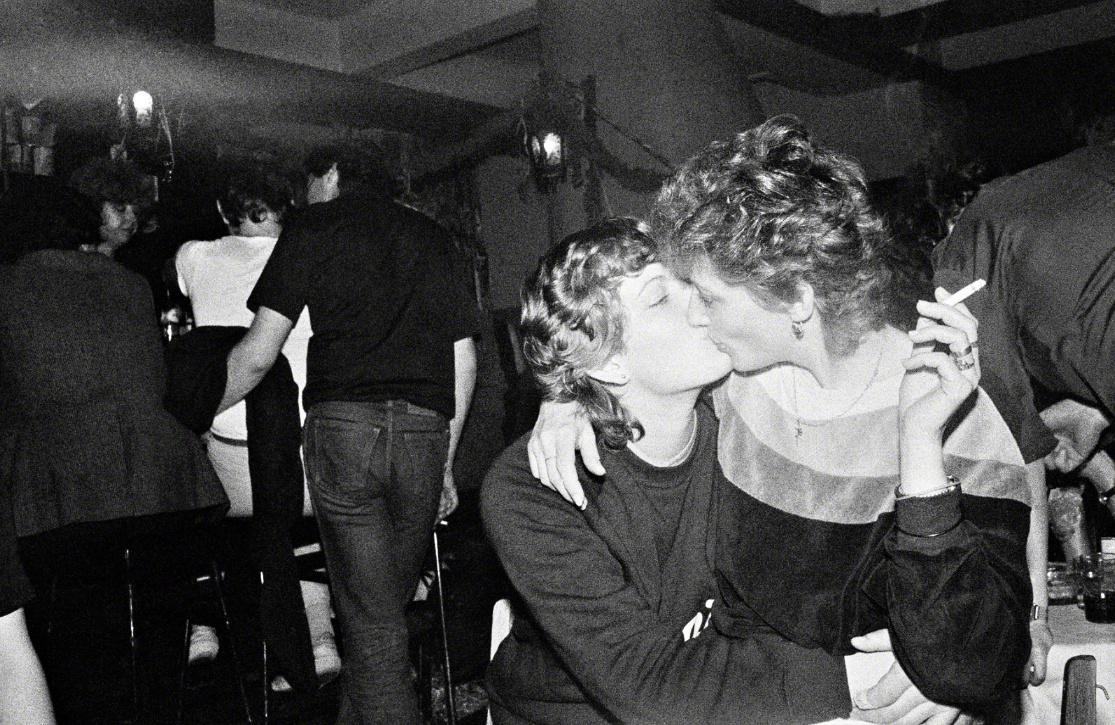

Gay clubs thrived in semi-underground culture in socialist Czechoslovakia – including ‘T-Club’, captured here by photographer Libuše Jarcovjáková in the 1980s.

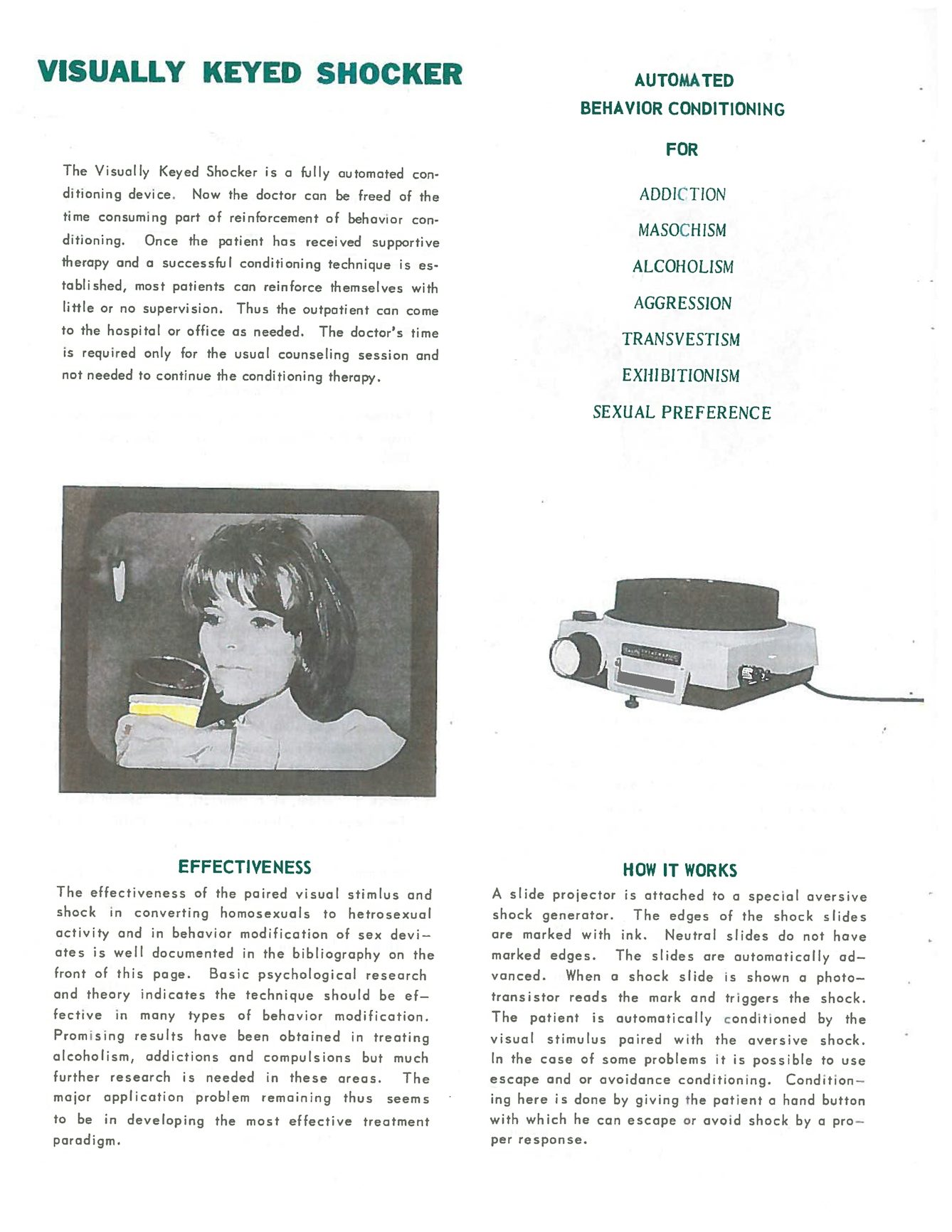

Aversion therapy was not only used in an attempt to change homosexual behaviour; psychiatrists targeted a whole range of unwanted ‘habits’ in the 1950s and 1960s. This opened up a market for medical technology companies to produce machines that could deliver mild electric shocks within the clinic, and even for patients to self-administer them in the comfort of their own home. This advertisement for one such device, the Visually Keyed Shocker, produced by Farrell Instruments in New England, was found in US medical journals of the time. An accompanying slide projector could be preset with images associated with unwanted thoughts, with the manufacturers claiming it could be helpful for treating everything from phobias and addiction, to ‘frigidity’ and paedophilia.

Changing the law

The change in Czech law didn’t begin an international domino effect, but it did offer a precedent that could be held up as an example in campaigns from then on. Freund himself emigrated to Canada in 1969, shortly after the failed Prague Spring reforms that led to a Soviet crackdown on academic and personal freedoms in Czechoslovakia. His evidence was used to back up the argument that being gay was as natural as any other inborn human trait. This, in turn, helped shape the debates that led to the American Psychiatric Association’s momentous decision to remove homosexuality from its ‘Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’ in 1973.

Aversion therapies continued to be used within institutions in other countries for years after Freund’s initial findings: in Britain, it took until 1967 for the law to change. Labour Home Secretary Roy Jenkins argued that sexuality was a deeply personal matter and it was not the business of the state to regulate it. The legal change saw an end to psychiatrists’ use of government-sanctioned ‘treatments’ within the criminal justice system – not just through behaviour modification, but also through anaphrodisiac drugs such as those used on Turing.

School students in Minnesota protest in front of a billboard advertising gay conversion therapy in 2015.

What are now known as ‘conversion therapies’ haven’t gone away: their use in private practice in the US and elsewhere today is testament to the enduring belief among many communities that human desire can be transformed, or at the very least suppressed. They do not form part of the standard repertoire of most mainstream psychotherapists, mostly being practised within faith communities and by lay ‘counsellors’. And they persist, despite decades of campaigning from LGBT campaigners worldwide. In 2018, however, ten US states made it illegal for mental health professionals to practise ‘gay conversion therapy’ with minors – suggesting that the regulators of sexual desire may themselves need to be regulated.

Find out more about the Hidden Persuaders project,examining ‘brainwashing’ in the Cold War, at Birkbeck, University of London. The War of Nerves, an exhibition about the psychological landscape of the Cold War, runs at the Wende Museum in Los Angeles until January 2019.

About the contributors

Charlie Williams

Charlie Williams is a postdoctoral researcher working with the Hidden Persuaders project at Birkbeck, University of London. His research explores Cold War culture through the lens of the human sciences with an emphasis on the psychological, emotional and economic relationships between humans and emerging 'psy' technologies.

Sarah Marks

Sarah Marks is a historian of twentieth century science and medicine, and Central and Eastern Europe. She is a postdoctoral researcher with the Hidden Persuaders project at Birkbeck, University of London, and is co-editor of the book 'Psychiatry in Communist Europe' (with Mat Savelli, Palgrave, 2015).

Daniel Pick

Daniel Pick is professor of history at Birkbeck, a psychoanalyst at the British Psychoanalytical Society, and the senior investigator on the Wellcome-funded Hidden Persuaders project. His publications include 'Psychoanalysis: A Very Short Introduction' (OUP 2015) and 'The Pursuit of the Nazi Mind: Hitler, Hess and the Analysts' (OUP 2012)