For thousands of years, twins have been a source of fascination in mythology, religion and the arts. Since the 19th century, they have also been the subject of scientific study and experimentation. William Viney, who is a twin himself, examines the significant and sometimes questionable use of twins in scientific research.

Twins share their environment and (in the case of identical siblings) much of their genetic make-up with another person from the moment they are conceived. For anyone studying human beings, this has made them perfect candidates for study and observation. By comparing them with each other and the wider population, scientists have gained insights into human nature – and nurture. For twin researchers such as Professor Tim Spector, founder of TwinsUK the UK’s largest adult twin registry, “Twins studies are the only real way of doing natural experiments in humans."

The eugenic foundations of twin research

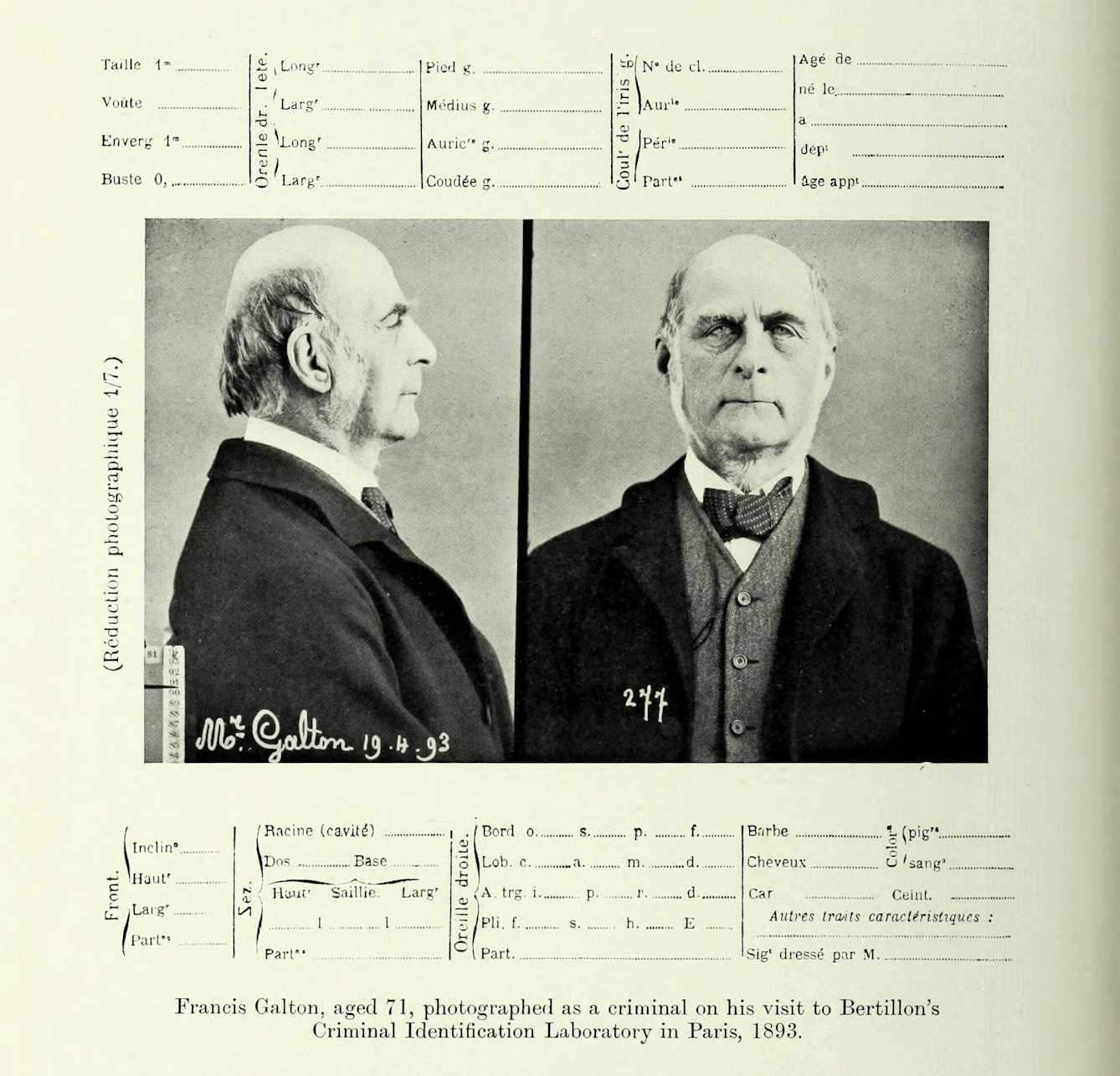

Putting twin people into scientific studies is usually traced back to Francis Galton (1822–1911), the British eugenicist. Galton’s studies of twins in the 1870s led him to conclude that twins grew dissimilar owing to the “development of natural characteristics” or “continue their lives, keeping time like two watches, hardly to be thrown out of accord except by some physical jar”.

Galton promoted using twins as a new method to support a biometric and eugenic approach to scientific research. Ever since, scientists and other experts have valued twins as “natural experiments” and “living laboratories” – nature’s gift to scientific reason.

Frances Galton, aged 71, photographed face-on and in profile as a criminal on his visit to Alphonse Bertillon’s Criminal Identification Laboratory. Like Bertillon, Galton was interested in hereditary traits for criminal behaviour.

Evidence from twin studies has been used to measure, control and manipulate how society is organised. Motivated by eugenic race science, German scientists of the 1920s separated twins into ‘identical’ (monozygotic) and ‘fraternal’ (dizygotic) control groups. They observed and quantified traits based on biological and environmental differences between twin pairs and groups made up of twin pairs.

Otmar von Verschuer (1896–1969) examines the eyes of identical twins as part of his research on twins. Verschuer was a professor of genetics and also a eugenicist in pre- and post-war Germany. One of his students was Josef Mengele, the Nazi war criminal who carried out experiments at Auschwitz concentration camp.

These experiments pioneered the technical and organisational research principles still used today in twin studies. Subsequent generations of twin researchers may seek distance from these histories and reinvent reasons to study twins – yet the treatment of twins as a ‘useful’ community to be studied continues today.

Twin insights into the nature of existence

History renders twins as heroes, gods and monsters, evidence of faith and speculative reason. For Christian theologians like St Augustine, for example, twins were evidence of free will’s triumph over the zodiac. Look at twins, argued Augustine, they are born beneath the same stars yet lead different lives and die at different times. Augustine used twins as evidence against fate in his fight with astrologers.

The constellation of Gemini, showing the twins Castor and Pollux.

Several hundred years later, physicist Albert Einstein and philosopher Henri Bergson used twins to debate the nature of time. In Einstein’s thought experiment known as his ‘Twin Paradox’, if one twin travels into space close to the speed of light, they would return to Earth younger than their twin sibling who stayed home. Bergson argued that time could not be understood simply in terms of science. Their public debates attracted huge audiences, who were confronted, again, by how twin narratives can be used to explore new truths about our existence.

As part of a NASA study, Scott Kelly spent a year in space, while his identical twin, Mark, stayed on Earth as a control subject.

In 2015 NASA made the Kellys, twin brothers and fellow astronauts, the subject of a case study in which Scott Kelly went into space and his brother Mark remained on Earth as a control case for comparison. For a year NASA’s Twins Study collected data to test how spaceflight affects oxygen-deprivation stress, increases inflammation, and causes changes in nutrients that influence gene expression. One of the things they discovered was that while high-speed space travel does indeed affect time, it also shapes how time affects the functions of the human body.

Siblings separated at birth

Twins have given instruction and entertainment in religious texts, medieval folk tales, theatre and television. One recurring story involves twins who are separated but eventually restored to a state of harmony. The fascination with twins “separated at birth” became another scientific method used to explore the relationship between nature and nurture.

‘Three Identical Strangers’ (2018) is a documentary about triplets Robert Shafran, Edward Galland and David Kellman, who were separated at birth but found each other by chance in the 1980s. Their reunion was a national media spectacle. Scientists from the Minnesota Study for Twins Reared Apart (MISTRA) asked them to join their study.

MISTRA was not the triplets’ first reared-apart study. Later, they discovered that they were part of another, study of separated twins and other multiple-birth siblings, being conducted covertly by Dr Peter Neubauer in New York.

Neubauer recorded the lives of twins and triplets who had been separated at birth by an adoption agency, which believed that they would develop their own identities if kept apart. Neither the adoptive families nor the children were told that they were twins or triplets. The film explored the ethics of keeping the study a secret. It also raised an important question relevant to all so-called natural experiments: do researchers shape the subjects they observe?

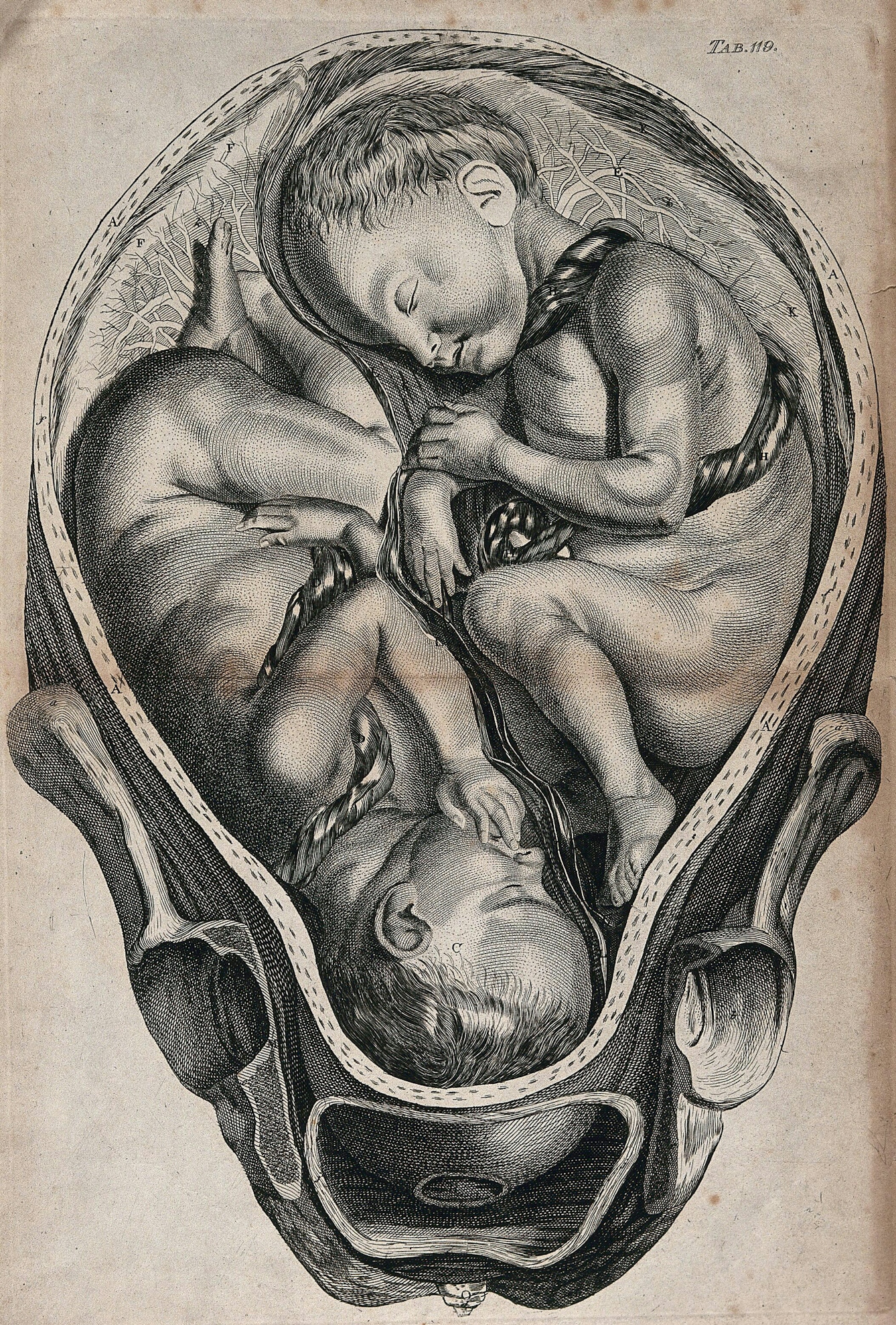

Biomedical interventions in twin births

On 6 June 1981 Stephen and Amanda Mays became the world’s first twins to be conceived thanks to in vitro fertilisation. As more sophisticated medical techniques and complex fertility markets developed in the last decades of the 20th century, twin birth rates increased dramatically, up 40 per cent in some countries.

Twin pregnancies and births increase many health risks for mother and babies, however. In the early 2000s the industry regulator in the UK, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, commissioned an independent review into excess deaths linked to twin pregnancies. As a result, it now campaigns to educate medical professionals and parents about the risks to mother and baby from implanting multiple embryos during IVF treatments. The policy highlights how twins, whether actively sought by parents or incidentally made, are often the result of competing reproductive, medical and financial pressures.

An 18th-century engraving of a uterus with full-term twins. By William Smellie after Jan van Rymsdyk.

Twins were also the result of a controversial procedure that produced the world’s first genetically modified humans. In November 2018, the birth of Lulu and Nana was announced at a press conference to a shocked audience. A team of Chinese scientists led by He Jiankui used a gene-editing technique called CRISPR-Cas9 to bioengineer their embryos in an attempt to lessen Lulu and Nana’s vulnerability to the HIV virus.

The procedure was widely criticised for the risks posed to the twins and the damage to the trust placed in science and scientists. He was later jailed. The scientific community has struggled to apportion collective responsibility for experiments such as these. As for Lulu and Nana, they have been hidden from public view to protect them from the repercussions of the illegal and controversial experiment that led to their birth.

Your digital twin

The many different scientific findings generated using twins have changed and challenged how we see ourselves. Bioscience has also helped to create many more twins through fertility treatments and (sometimes questionable) biotechnologies. Now in the digital age, twin science is moving into the virtual world.

We may be slowly getting used to the idea of avatars of ourselves in the virtual world, but a digital twin could be something more. It is hoped that these ‘data doubles’ would use data to track and predict our future health conditions. They could test ‘what if’ scenarios, such as surgical procedures on a digital model of your heart, for example. And a digital twin could help a medical team to assess the likely outcome of different therapies – a virtual as opposed to a living laboratory of your body.

Although the selling point would be an exact real-time data double, personal to you, in order to be accurate and reliable, your digital twin would in fact have to be an aggregate drawn from large collections of health and medical data – a ‘virtual laboratory’ of many.

About the author

William Viney

William Viney works at the Patient Experience Research Centre at Imperial College London. His writing has appeared in Cabinet, Critical Quarterly, Frieze, and the Times Literary Supplement. He is the author of two books, ‘Twins’ (2021) and ‘Waste’ (2014).