For at least 600 years Europeans have been unsatisfied with the way they look. Today’s “vampire facelift” is only the latest in a series of unappealing beauty treatments, from the pointless to the poisonous.

Those of a squeamish disposition might be put off by a procedure with a bloodcurdling name like “vampire facelift”, but this non-invasive cosmetic treatment is enjoying great popularity at the moment. The procedure stimulates skin rejuvenation through technology known as Selphyl. A small amount of blood is drawn from the client’s arm and spun in a centrifuge to separate out the platelets. The platelets are then injected back into the face to keep the recipient looking youthful. The results are, as ever with this type of procedure, fleeting.

You might think that we in the 21st century are uniquely obsessed with youthfulness. Yet people in the past were equally eager to turn back the clock, and their beauty regimes could be just as futile as, and often far more toxic than, our own.

Fit for a queen

To maintain her persona as the ageless ‘Virgin Queen’, Elizabeth I used kohl eyeliner, lipstick made from plant dye and beeswax, and a white foundation of ceruse – a corrosive blend of vinegar and white lead. Darker complexions were associated with the weather-beaten poorer classes who had to labour outdoors, and well into the 18th century, wealthy socialites coveted powders that gave them that cake-white look.

Both women and men applied rouges and lipsticks comprising carmine (crushed beetles) and Plaster of Paris to enhance their complexions. When used over long periods, lead-based whitening cosmetics could cause serious side effects – such as nausea, headaches, blindness, or even death.

Potions and elixirs for improving one’s appearance proliferated in the 18th century. Everything from hair-restoring creams to slimming pills were sold, each purporting to be a miracle cure.

Many nostrums were invented to conceal telltale signs of disease. For instance, before the discovery of penicillin in 1928, syphilis was especially feared, partly because it left unsightly lesions on the face. Women covered these defects with ‘beauty spots’ made of fine black velvet, or even mouse skin.

Such shortcuts to a healthy constitution have always been prized, no matter how outlandish.

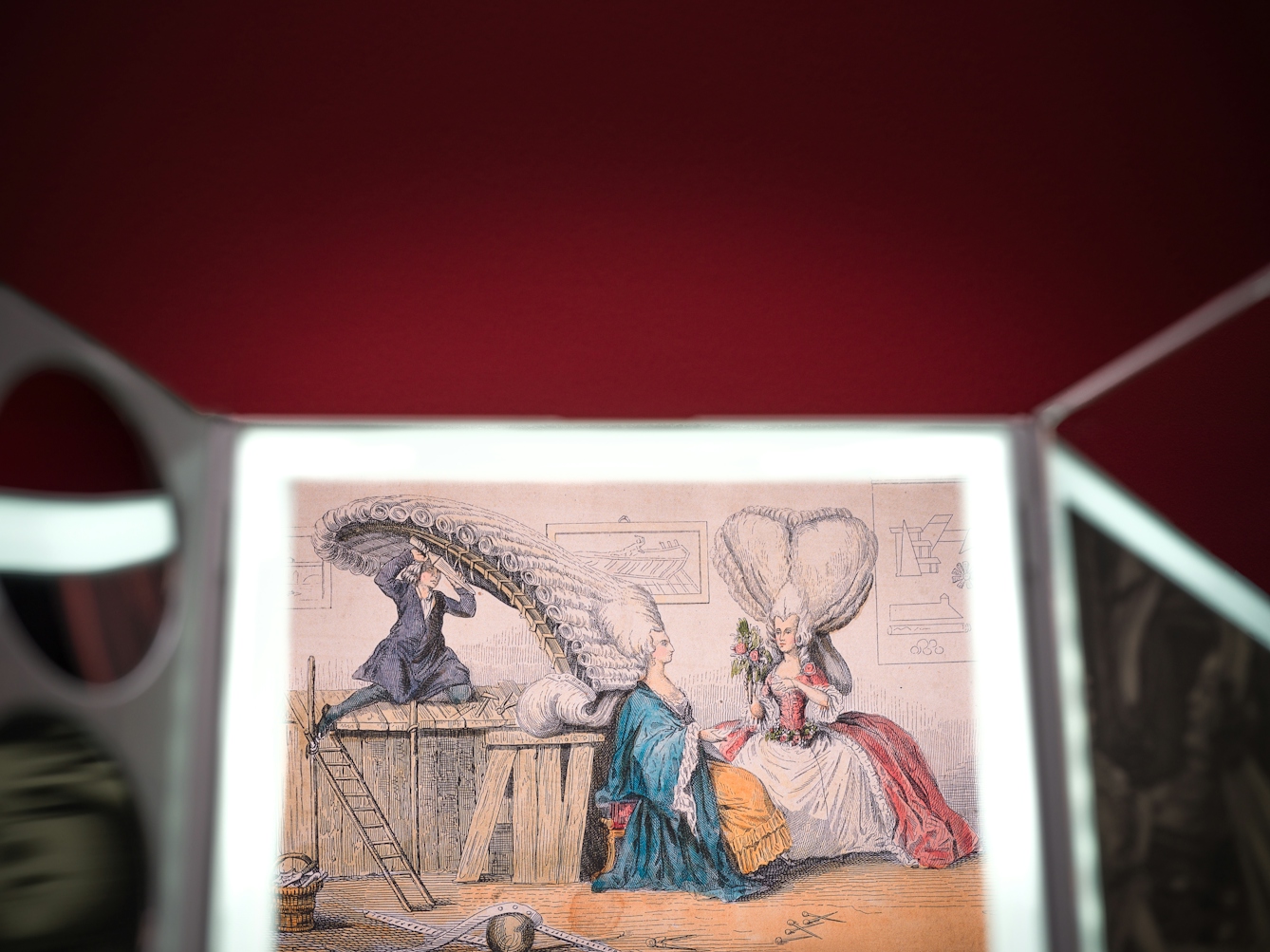

And then there was the hair. During the Georgian period, women went to great lengths to perfect the design of their wigs. By the latter stages of the styling craze, they were known to have to sit on the floors of their carriages because their hairdos were so lofty, and so loaded with accessories, such as fruits, feathers, and even model ships.

Caricaturists had a field day with this trend. As the 1770s progressed, satirical engravings showed the wigs growing taller and taller, and barbers are shown resorting to the use of ladders in order to put the finishing touches to their creations.

As striking as these coiffures were, they could also be unsavoury. Barbers often used lard so that a wig would adhere more successfully to the scalp. Often this attracted vermin, which burrowed into the elaborate hairpieces. Those who could afford to maintain extravagant hairdressing regimes frequently suffered from infestations of lice or fleas, as well as an array of scalp problems, due the unhygienic condition of the wigs.

Shaping the body beautiful

And ladies paid as much attention to their bottoms as to their tops. A newspaper report from the 1770s tells of “cork rumps”, which were false buttocks designed to give women a Kardashian-esque backside. The piece goes on to tell of a woman who fell into a river while pleasure-boating, but was saved from drowning by her buoyant cork backside.

Men could be equally concerned about their silhouettes, and none more so than the peacock-like George, Prince of Wales, later to become George IV. By the end of the 18th century he was cramming his bulky midriff into a whalebone corset known as a ‘Bastille’. But even he could not hide his expanding frame indefinitely, and in later years he was lampooned as “the Prince of Whales” by body-shaming caricaturists.

In an age before “Doctor Google” the publishing industry offered health tips in abundance to an eager public. One such example, published in 1750, was ‘The Old Man’s Guide to Health and Longer Life’, by John Hill, MD. This proved popular, and ran to several editions. One of its recommendations was a vigorous rub-down with a “flesh brush” as a substitute for actual exercise. Such shortcuts to a healthy constitution have always been prized, no matter how outlandish, as recourse to such measures as electronic muscle stimulators will attest today.

Poisonous Victorian potions

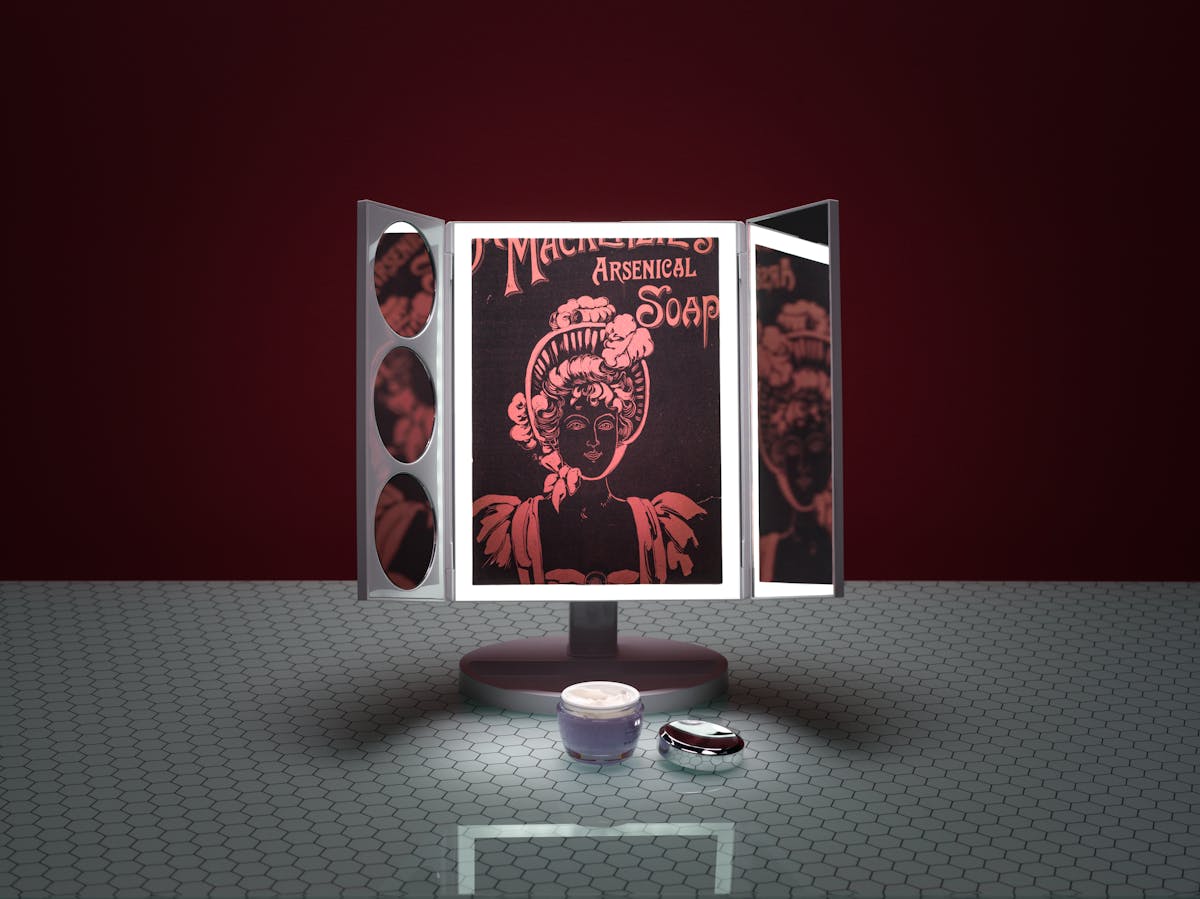

The Victorians were no less vain than their Georgian counterparts when it came to their beauty regimes. In the late 19th century, newspapers advertised tins of Arsenic Complexion Wafers, promising the eradication of imperfections, like redness, acne, blackheads, and freckles – with additional claims of curing malaria, rheumatism, and habitual constipation!

Poisonous substances regularly appeared in Victorian products, such as belladonna, taken from the plant deadly nightshade, which was used to dilate women’s pupils. This was seen to make them more attractive, and modern human behaviourists would back this up, given what we now know about the action of our pupils when we are excited by the presence of the object of our affection.

Even radium became a fad in the beauty industry after it was discovered by Marie Curie in 1898. It appeared in all kinds of products, like cigarettes, lipsticks, and toothpastes – right up until the 1950s. One radium hand cream claimed to take “everything off but the skin”.

So, next time you walk through a department store and feel tempted to purchase the latest anti-ageing product, spare a thought for our ancestors, and ask yourself if you are being tempted by just another one of history’s short-lived beauty fads.

About the contributors

Dr Lindsey Fitzharris

Dr Lindsey Fitzharris is a bestselling and award-winning author with a doctorate in the History of Science and Medicine. Her debut book, ‘The Butchering Art’, won the 2018 PEN/E O Wilson Award for Literary Science and was shortlisted for both the Wellcome Book Prize and the Wolfson History Prize.

Kathleen Arundell

Kathleen is a freelance photographer working in the culture and heritage sector. She works in a range of museums across London, and loves all things science and art.