Probably best known now as the name of a high-spec electric car, the original Tesla was a hugely influential engineer and inventor. Find out how a whole quack industry in ‘violet ray’ therapy was developed from one of his greatest discoveries.

Tesla, quacks and violet rays

Words by Surya Bowyer

- In pictures

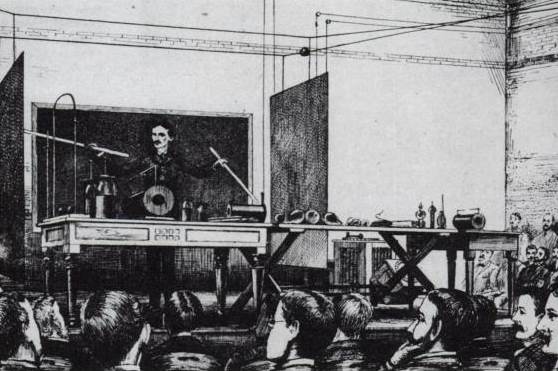

On the evening of 20 May 1891, the American Institute of Engineers gathered in a lecture hall at Columbia University. They were about to witness a show of science that would install the engineer Nikola Tesla as one of the greatest inventors of the new age of electricity.

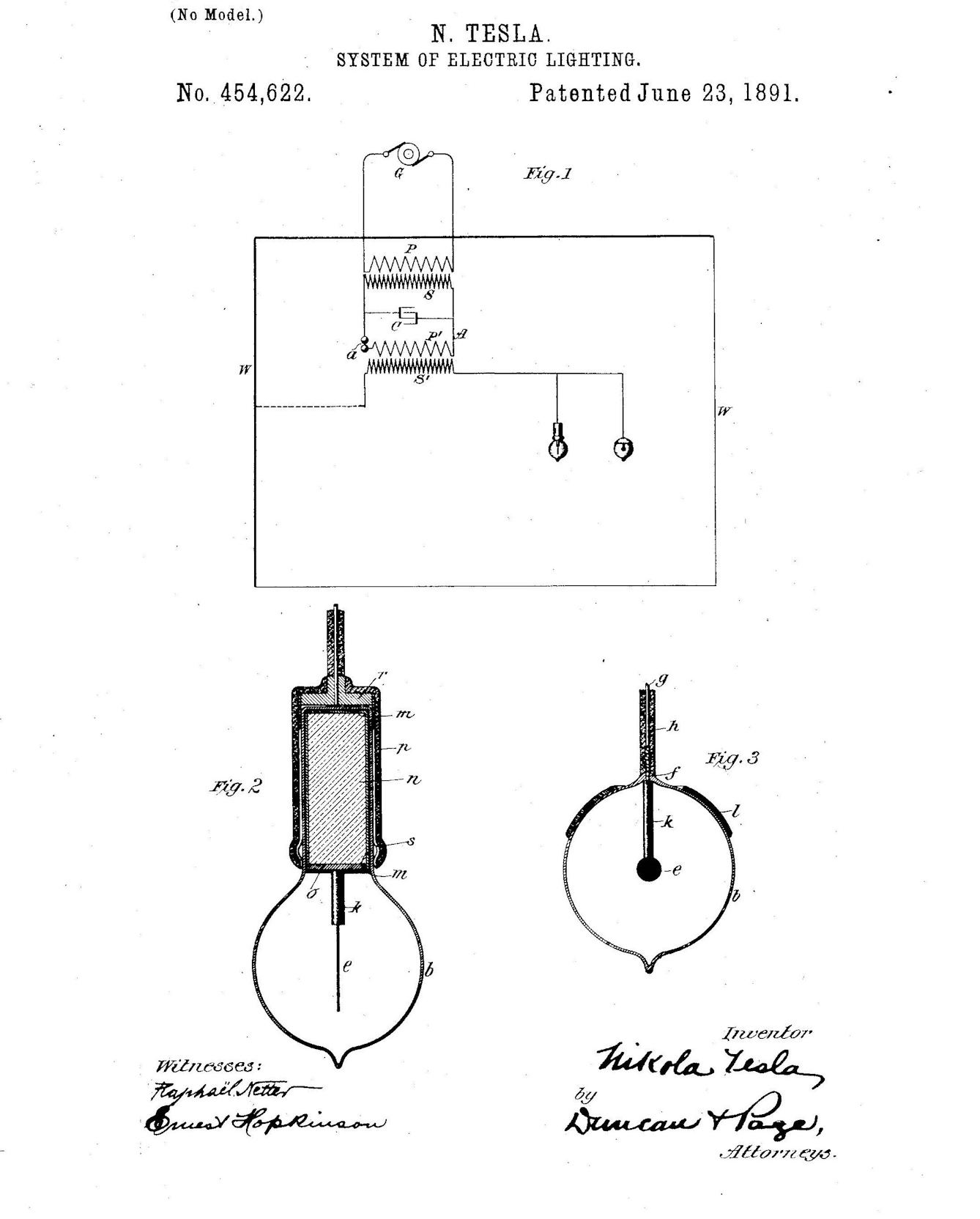

The star was the Tesla coil, for which Tesla had just filed a patent. The design was radical: Tesla replaced insulation with an air gap between the primary and secondary coils (labelled a).

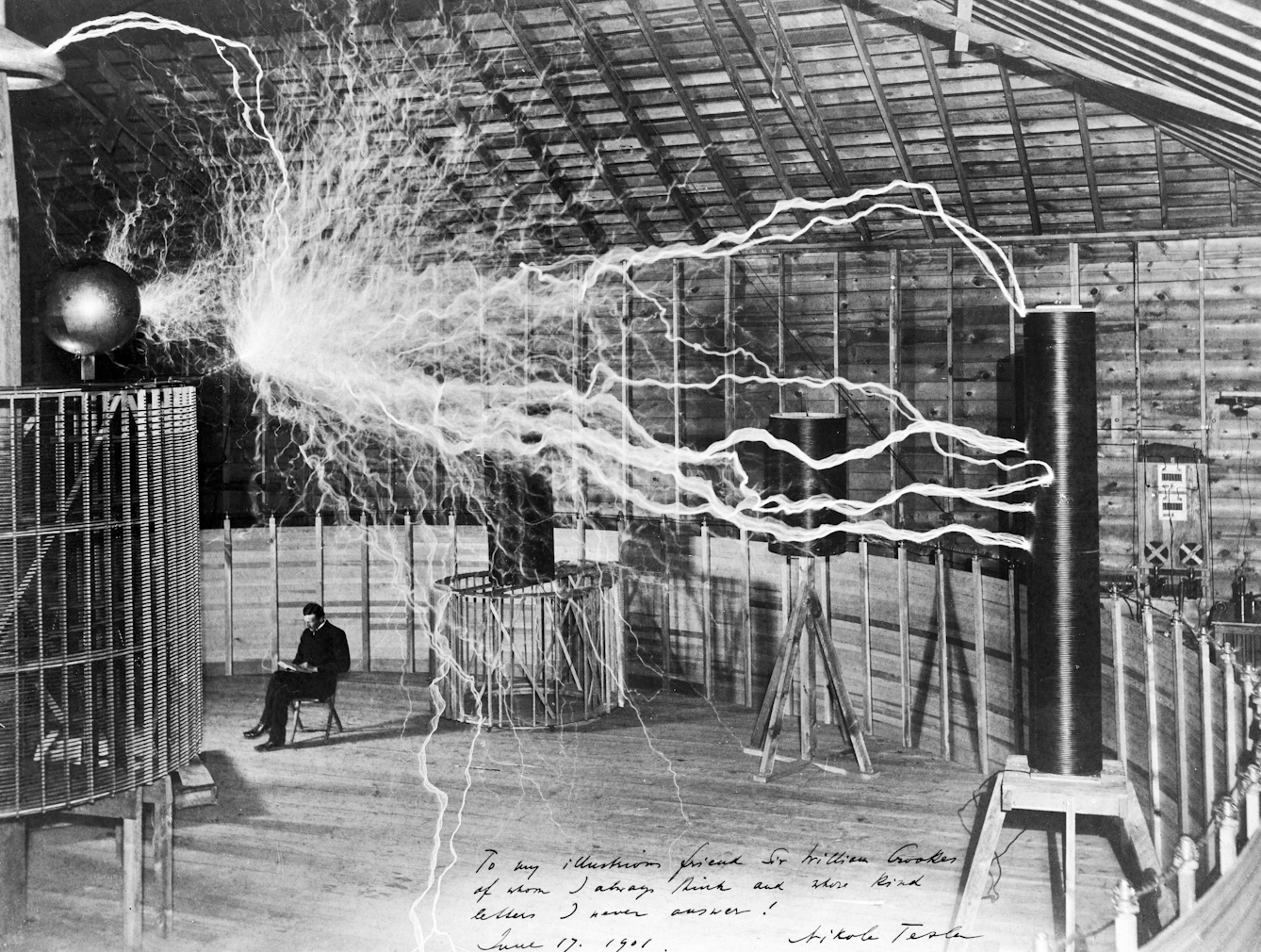

In this photograph, electricity is discharging across the air-gap in Tesla’s circuit. The Tesla coil produced currents with a far higher frequency and voltage than other devices of the time. And it was cheaper, requiring only one wire to run to each bulb, rather than the conventional two.

Tesla’s coil allowed him to replace the filament used in lamps, such as these manufactured by Thomas Edison, with a more solid piece of carbon. Filaments were, according to an 1891 report in ‘The Daily Nevada State Journal’, “the most serious objection to the present form of incandescent lamps”. Because they were fragile and liable to break, 50,000 per day had to be made just in the USA.

Tesla and Edison competed over more than just filaments: both bid to provide the electricity for the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. Edison saw his direct-current system trounced by Tesla’s alternating current. Tesla not only delivered the Fair’s electrical infrastructure but also held dramatic demonstrations of the possibilities of alternating current. His exhibit at the Exposition is pictured.

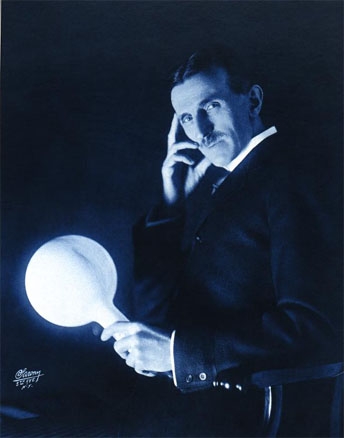

One of Tesla’s favourite demonstrations was wireless lighting. Here, Tesla holds a glass bulb that has a single electrode inside it. A Tesla coil (off-camera) creates an electrostatic field in the air, which ionises the gas in the bulb and causes it to glow.

Tesla suggested that different wavelengths on the electromagnetic spectrum could be used to treat medical conditions. Jacques-Arsène d’Arsonval and Paul Oudin, pioneers in the field of electrotherapy, agreed. They modified Tesla’s device to create an electrotherapy instrument. Tesla also developed an instrument, and it was not long before numerous companies began peddling their own versions under the name ‘violet ray’.

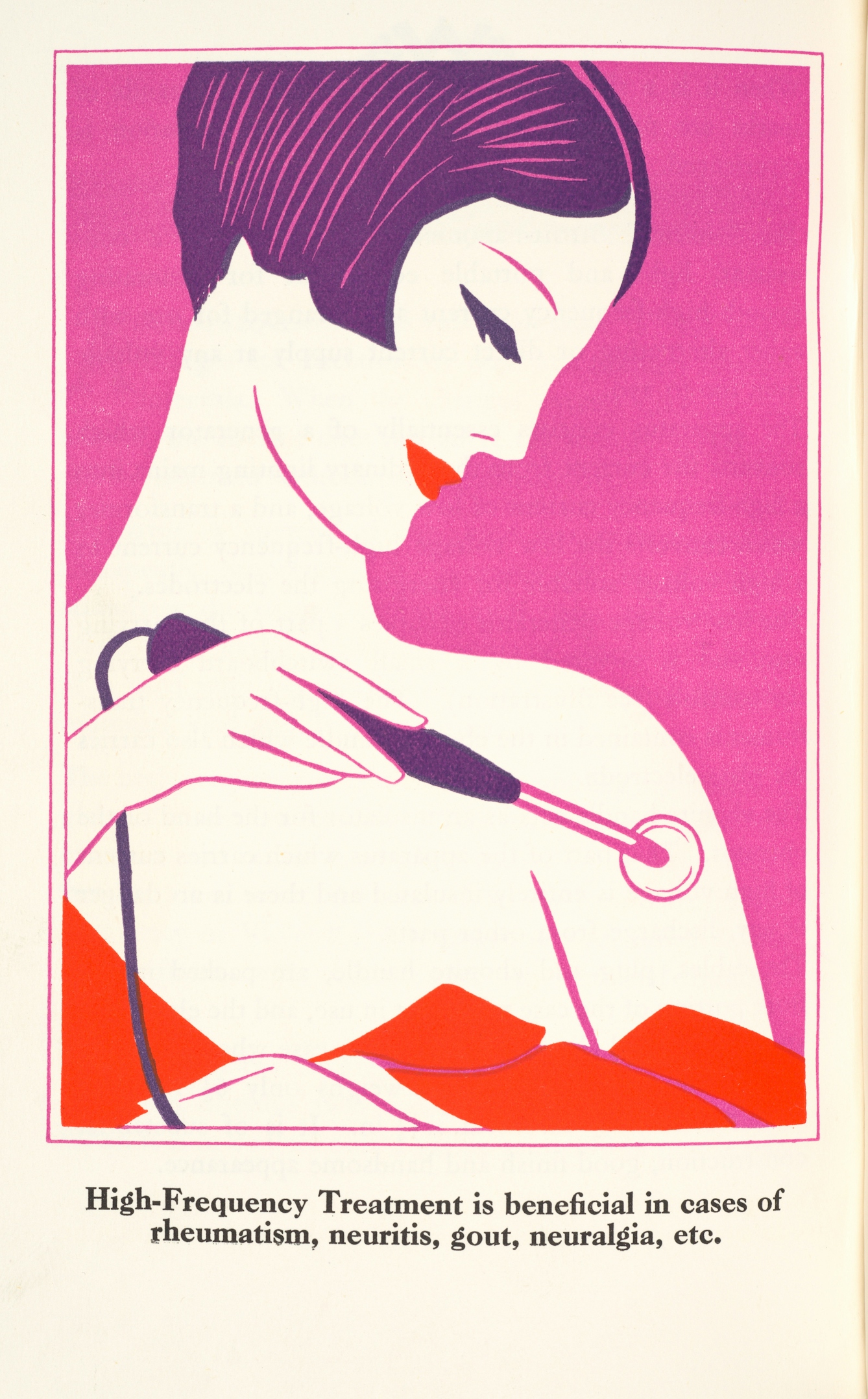

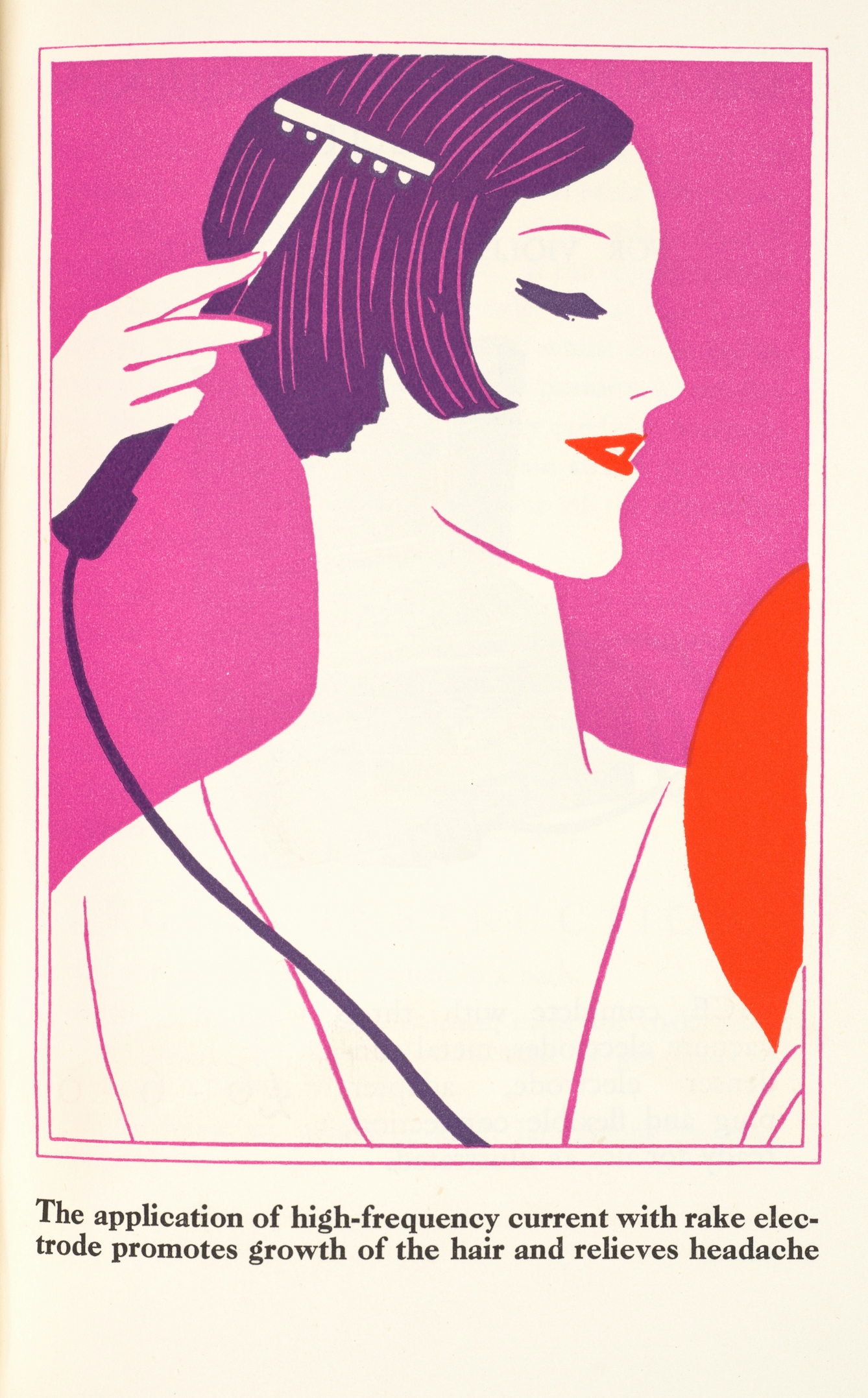

The violet ray became popular among doctors making house calls, as it could plug into a lamp socket and, unlike most other high-frequency electrotherapy devices, could run on either alternating or direct current. Many advertisements emphasise the device’s ease of use and paint a picture of its target market: young, affluent women.

Much like Tesla’s bulb, the violet ray had a partially evacuated glass end, which users would put against their skin. Sparks would then discharge across the outside of the glass, producing ozone and ultraviolet rays as by-products. The implied nudity in these advertisements supports historian Carolyn Thomas de la Peña’s claim that advertisers often used sexualised images of young women to sell the device.

Manufacturers referred to the glass ends as ‘electrodes’ and created a range of shapes that allowed users to target different areas of the body when applying current. They claimed the device could cure all manner of ills, including: headaches, dandruff, premature baldness, greying hair, insomnia, rheumatism, neuritis, gout, neuralgia, weak lungs, nervousness, hoarseness of voice, sallow complexion, and a range of dental disorders.

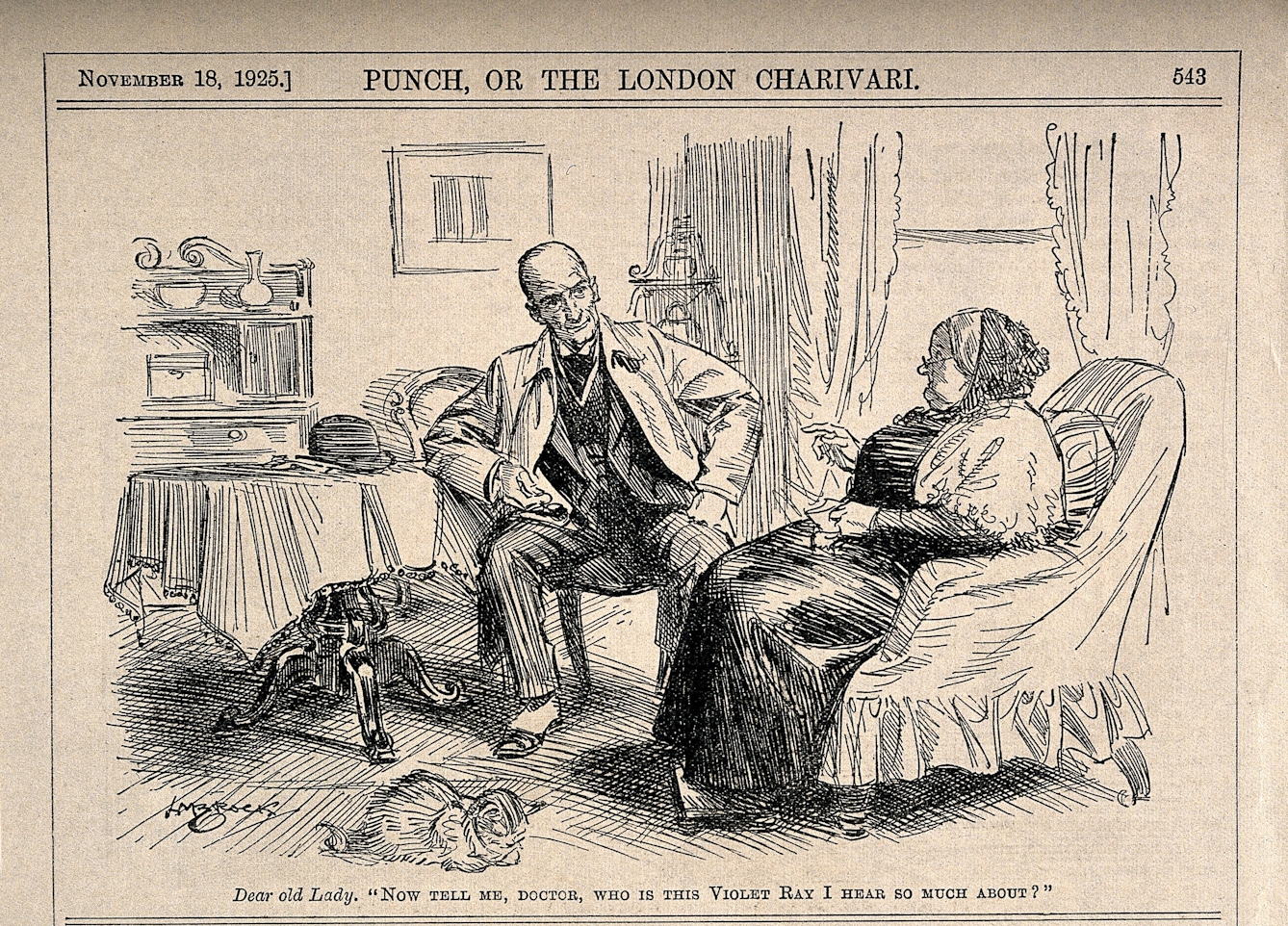

It seems everyone had heard of the violet ray. This cartoon from the hugely popular satirical magazine Punch shows an old lady confusedly asking about a woman called Violet Ray, and would have only been funny if readers knew about the electrical device.

Bold health claims about the violet ray device, coupled with its wide popularity, proved to be its downfall. A 1951 American court case found the device totally unable to treat the vast majority of the conditions claimed by manufacturers. Shortly afterwards, the Food and Drug Administration seized several units, and more court cases and legal action followed. By the end of the decade the violet ray had largely disappeared. But today, if you search online, it’s possible once again to purchase a violet ray device and read wild claims about how it will improve your health. Buyer, beware!

About the author

Surya Bowyer

Surya Bowyer is a writer and educator from London. He is interested in the intertwined histories of media and technology.