From her early teenage years, medical historian Jaipreet Virdi found her life distressingly punctuated by episodes of severe monthly pain. And like millions of other women over the centuries, her story starts with being told her agony was normal, and perhaps exaggerated or even imagined.

Thousands of years of women’s pain

Words by Jaipreet Virdiartwork by Anne Howesonaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Serial

From adolescence I was told that pain is a normal part of growth. My pain was simply the pain of my body growing, a marker of my journey towards adulthood that began with menarche (the first occurrence of menstruation). Like many other girls, I was embarrassed, perhaps even frightened, by the first spots of blood. Whispered solutions and targeted advertising had instructed me what to do, and my mother’s realisation of this new change reassured me I was doing things correctly.

Nothing, however, prepared me for the monthly pains. I cried as I bled, clutching my stomach. It was just cramps, I kept telling myself. Muscle contractions inside my body to help the blood shed, supposed to last seven days. If I was lucky, then only the first two days would be terrible. The hot-water bottle became my companion, its weight and heat applying soothing pressure to relax my lower abdomen, with pillows placed under my lower back to elevate my hips and lessen the pain. On worse days, over-the-counter remedies were needed, but I never got as far as experimenting with more drastic methods to alleviate the cramps.

But pain, disability theorist Tobin Siebers reminds me, is not a friend.

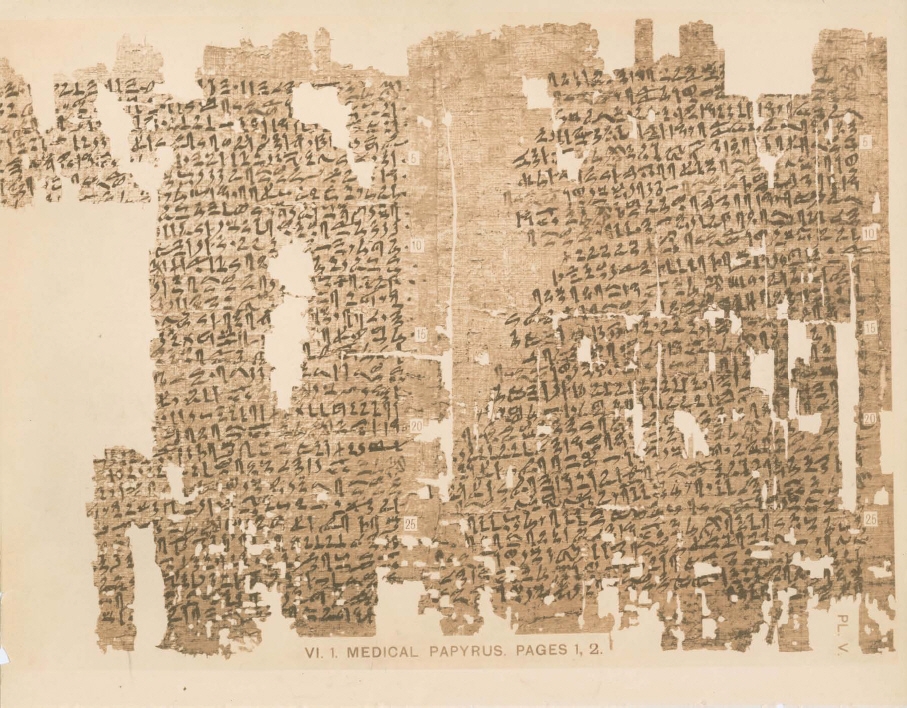

Pain, and specifically women’s pain, is an age-old problem: the Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus has been dated to c. 1800 BCE.

The monthly bleeding might be natural, but I never questioned whether my anguish was part of the ordinary experience or a sign of something worse. It seemed normal to skip gym class on account of a heavy flow and terrible backache, just as it was to lie on the bathroom mat, my feet on the cold tiles, waiting for the pain that consumed my entire body to pass.

According to historian Joan Jacobs Brumberg, North American girls are taught to regard menarche as a hygiene crisis rather than as a maturational event. This has complications for how they perceive menstrual pain: out of embarrassment, and perhaps even of expectation of suffering, they don’t disclose the severity of their pain. Or else they think it’s a part of the normal monthly process, an experience that needs to occur in private.

More: The 19th-century doctor who promised better periods by limiting mental exertion.

One of the most ancient medical documents, the Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (2100–1900 BCE), outlines issues of healthcare pertaining to the uterus, including the wandering womb. According to this theory, when the uterus is not satisfied by impregnation, it could leave its deep-seated place and move around the body. Wherever it wandered, whatever organ it ended up pressing itself against, would be the new site of illness, which could only be treated by coaxing the uterus back into place through incense, fumigation, oils or milk.

The papyrus also recorded cases of what we now call dysmenorrhea: pain during menstruation. But throughout history this pain was routinely dismissed as psychosomatic, the result of poor lifestyle management or punishment for delayed pregnancy. It was frequently denied the status of real pain.

Female complaints

Rapid developments in medical technology in the 19th century meant that the ‘objective’ assessment of symptoms became paramount to doctors. However, some pain cannot be seen, measured or quantified, and ironically, male medics’ subjective prejudice stigmatised patients with invisible, gynaecological pain: women were more likely than men to be undertreated for pain, and women of colour more so than white. After all, the overtly emotional nature of a woman – cis, non-binary, trans – made her less credible when determining the reality of her body’s signals.

These perceptions have become culturally rooted in healthcare systems, in which women’s pain is often overlooked, dismissed, misdiagnosed or mistreated more often than men’s pain.

It is ableism that makes suffering acceptable, that forces people to appear to be normal by suppressing the fever, nausea, fatigue and other bodily issues that accompany pain. “To conceive of another person’s pain,” writer Rachel Vorona Cote explains, “is to undertake an obscure endeavour, one that is often muddled by vexation, strained analogies and, in the crux of it all, doubt.”

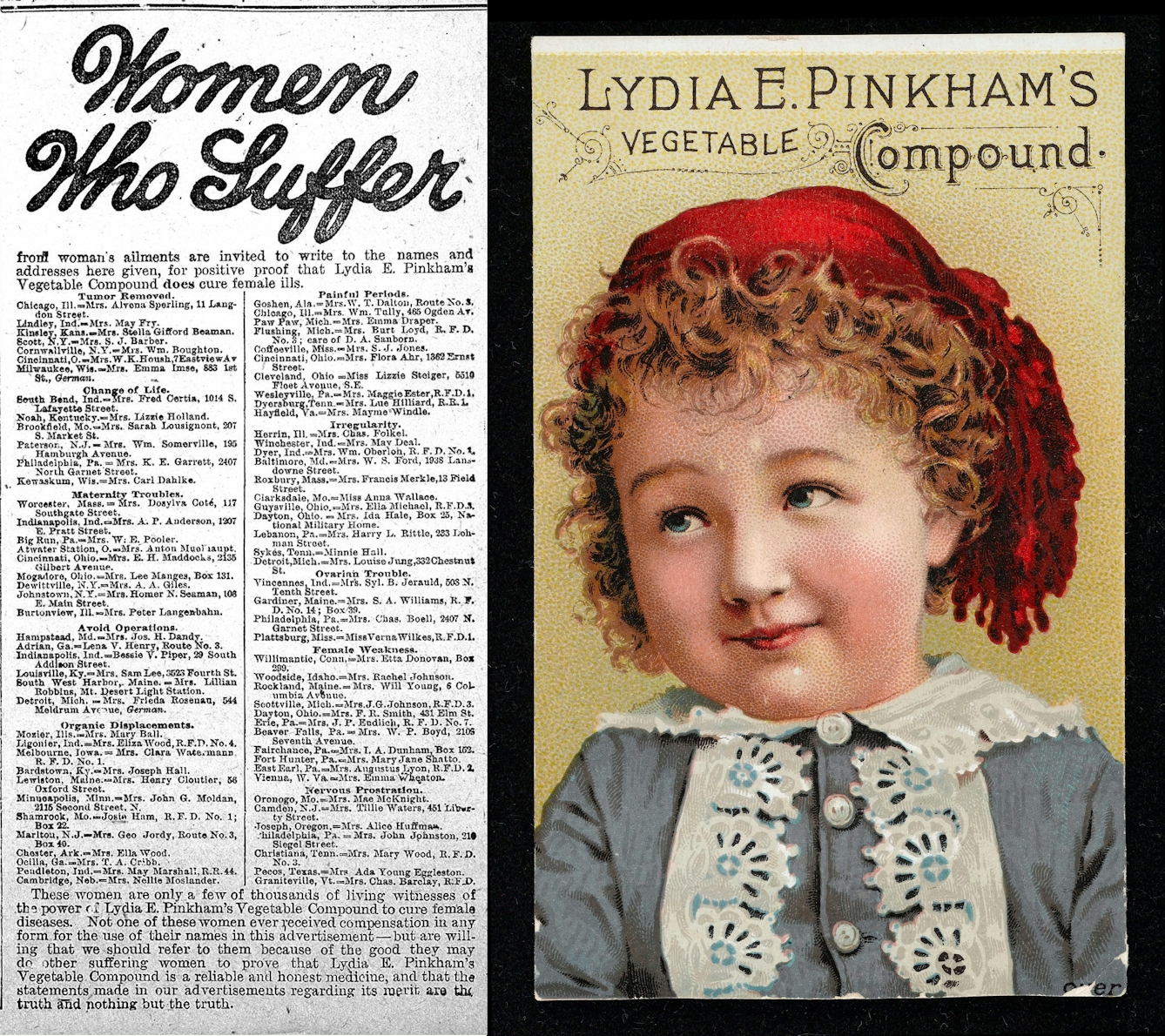

Lydia Pinkham’s medicine catered for women underserved by the formal medical establishment.

Other sufferers can certainly recognise debilitating pain. When Lydia E Pinkham devised her vegetable compound in 1875, she knew that teaching women how to care for their bodies was a necessary component of her progressive ideology. Treatments for ‘female complaints’ – a catch-all 19th-century diagnostic term for various conditions, including painful menstruation and prolapsed uterus – and ‘nervous, ailing women’ could additionally serve as an essential aid for a young woman’s ‘growing pains’ as she approached marriageable age. Pinkham’s homebrewed remedy was, in other words, a product appealing to those aspiring for inclusion in the ‘cult of pure womanhood’.

There was a genuine belief that women who experienced severe pain on ovulation and menstruation were making it up.

The medical literature said nothing about these female complaints until nearly 30 years after French writer Jules Michelet declared the 19th century as “the age of the womb”, reflecting a preoccupation with women’s reproductive system and sexuality. It is the reason, for instance, why American physician Dr Robert Battey’s argument for removing healthy ovaries for treating menstrual complaints and sexual disorders became popular, even though the evidence to support its benefits was seriously lacking.

There was a genuine belief – in both medical and popular literature – that women who experienced severe pain on ovulation and menstruation were making it up, exaggerating it, as part of their hysterical feminine nature. Only an ‘alienist’ – a psychiatrist – could help bring a woman’s body back into alignment.

It was not until 1921 that this debilitating condition was named: endometriosis.

About the contributors

Jaipreet Virdi

Dr Jaipreet Virdi is a historian of medicine and disability based at the University of Delaware. Her first book, ‘Hearing Happiness: Deafness Cures in History’ is available where books are sold. She is currently working on her next book, ‘An Invisible Epidemic: The History of Endometriosis’.

Anne Howeson

Anne Howeson develops projects concerning place, time and communities. She is a Jerwood Drawing Prize winner with drawings in the collection of the Museum of London, the Guardian News and Media, St George’s Hospital and Imperial College London. She was shortlisted in 2014 for the Derwent Art Prize and the National Open Art Award, and in 2017 for the Ruskin Prize. She has twice been an invited artist with ING Discerning Eye. As a tutor at the Royal College of Art she promotes drawing in all its forms – through process, outcome and as a way of thinking.