Western magicians and mind readers have long used the imagery of the ‘mystic East’ to reinforce their special powers and difference from ordinary audience members. Shelley Saggar argues that in today’s racism-infused political climate, it’s time to stop invoking these easy stereotypes.

In Western traditions, magic is understood in terms of opposition: it is superstitious rather than scientific; irrational rather than reasonable; strange rather than familiar.

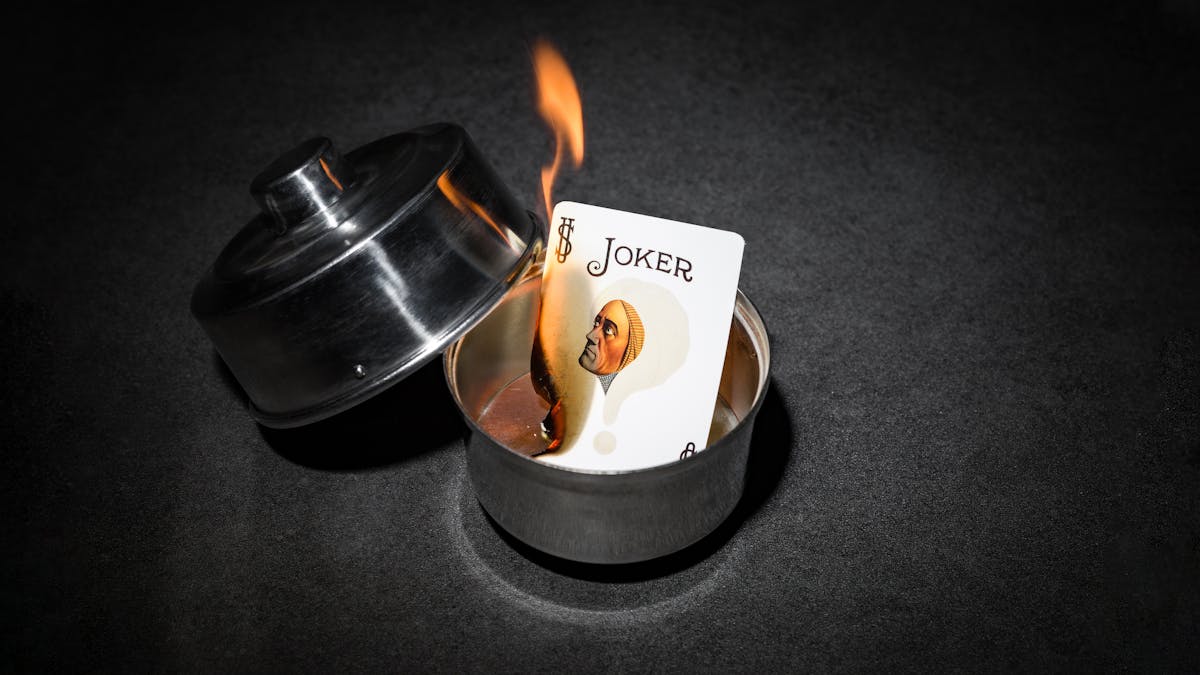

Western magical performers have long relied on cultural motifs to create a sense of spectacle and mystique, and a motley assembly of ‘exotic’ stereotypes have come to represent supernatural dangers and delights to awestruck audiences the world over. These range from Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics to turban-wrapped mind readers and the infamous ‘Indian rope trick’.

These seemingly innocent borrowings from other traditions ultimately reinforce stereotypes about the threat of foreigners. Through their association with deception, misdirection and trickery, these stereotypes also reveal the psychology of just who we expect to deceive us.

The word magic stems from the Ancient Greek magos, denoting a member of the Persian educated classes. The word itself shares an etymological association with magi, familiar from Christian mythology as the title given to the Three Wise Men who came bearing exotic gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh upon hearing of the birth of the infant Jesus.

The roots of exoticism are plain to see: learned scholars who are identified in the Bible as being “from the east” (Matthew, 2:1) are represented as those with understanding of alternative knowledge systems that diverge from our own. Practitioners of the magical arts, then, are immediately associated with cultural and intellectual ‘others’. From these roots we can see evidence of the drive to draw upon Eastern influences to create a sense of authenticity.

Turbans, technology and trickery

Arguably one of the most famous mind readers of the 1920s, Claude Alexander Conlin was a master of marketing as well as mentalism. His iconic posters give some sense of the myriad epithets he employed to distinguish his act above all others: ‘Alexander: The Crystal Seer’, the unfussy ‘Alexander’, and ‘Alexander: The Man Who Knows’.

Alexander carefully selected elements of recognisably ‘Eastern’ cultural dress: paisley-printed robes and an elaborate turban, complete with a large feather, set with a jewel. This costume presented his audiences with an identifiable image of a mysterious ‘other’ who possessed secret knowledge that gave him access to the most intimate corners of their minds.

Alexander’s invocation of the ‘other’ wasn’t just limited to his wardrobe. In several of his illustrated posters his complexion has been strategically darkened too. But his employment of ‘Eastern’ imagery was nothing new. Rather, he was playing to an established set of stereotypes in Western culture, evidenced in William Beckford’s troupe of Oriental occultists in his novel ‘Vathek’ (1786), Wilkie Collins’s “cursed Indian jewel” in the 1868 novel ‘The Moonstone’ and, as Palestinian-American cultural theorist Edward Said has so eloquently argued, in French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme’s 1879 painting ‘The Snake Charmer’.

The key to Alexander’s mind readings was an electronic earpiece that allowed him to receive transmissions from an assistant, who communicated crucial information about the audience participant. Cleverly concealed inside the turban wrappings, the device was hidden in plain sight, inside the very aspect of Alexander’s costume that explicitly coded him as a mysterious foreign figure.

The assumption that Alexander’s character possessed mystical secrets that could penetrate even the most rational Western minds, and the implicit knowledge that this was, after all, a clever ruse, even a con, reveals a particularly insidious insight into the perceptions of the audience. They expected this kind of danger and deception from a man so obviously coded as Eastern.

Even today, performers are continuing a long tradition of stereotypes about how we expect cultural ‘others’ to deceive us.

Alexander’s character acted as an antithesis to the sensibilities of his Western audiences. He was mystical where they were rational; his act threatened to reach into the safe distance between performer and audience; and crucially, he was ‘other’ while they were familiar. It is these artificial yet significant cultural oppositions that the authenticity and, ultimately, success of Alexander’s act played upon, binaries that persist to this day.

The frisson of foreign mysticism

In 2008, in the heart of London’s theatre district, the Garrick Theatre advertised a new show from popular British stage magician and television personality Derren Brown. The promotional poster that was used outside the theatre, as well as in the surrounding marketing campaign, depicted Brown turbaned and resplendently robed. The outfit would have been instantly recognisable to enthusiasts as a reference to Alexander.

Even for those less familiar with the iconography of magical paraphernalia, the promises of an exotic Eastern mysticism in Brown’s promotional guise were surely still easy enough to read. Almost six decades after Alexander’s passing, the invocation of a foreign mysticism laced with the implicit fear of mind control and ideological domination still resonates.

We can see this in the contemporary hysteria about immigrants ‘invading’, refusing to assimilate and supposedly forcing their cultures upon their adopted homelands that crowd newspaper pages, online forums and politician’s speeches.

In a political climate such as this, the appropriation of cultural signifiers to advance a promise of implicit, however entertaining, deception can no longer be afforded the privilege of remaining ‘just a costume’. Even today, performers are continuing a long tradition of stereotypes about how we expect cultural ‘others’ to deceive us. Perhaps, then, we should work to create a new visual language to communicate magical spectacles, one that does not rely on the opposition of others.

About the contributors

Shelley Angelie Saggar

Shelley Angelie Saggar is a research practitioner working in material history, museum cultures and decolonial methodologies. Her current work concentrates on the complicated colonial histories of secret, sacred and otherwise culturally sensitive items in the Wellcome historical medical collections housed at the Science Museum.

Thomas S G Farnetti

Thomas is a London-based photographer working for Wellcome. He thrives when collaborating on projects and visual stories. He hails from Italy via the North East of England.