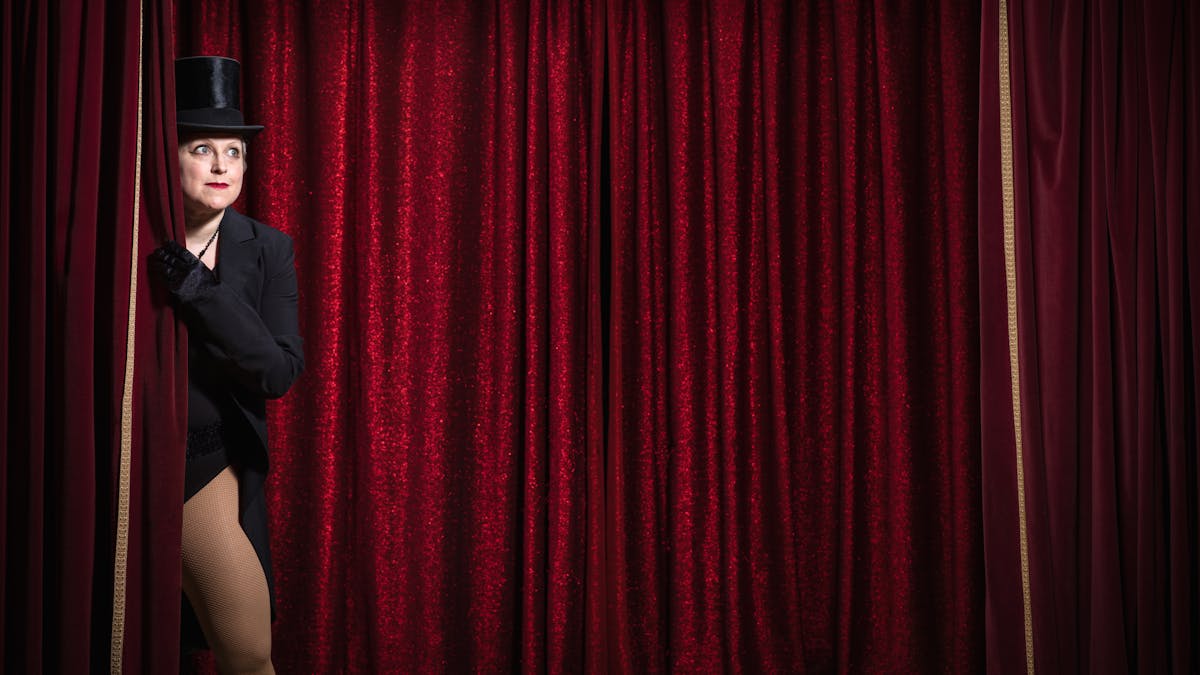

Colluding with an audience that wants to believe, the magician’s assistant has her own armoury of tricks to help maintain the illusion. Performer Naomi Paxton takes us inside the ingenious world of onstage magic.

I’m inside a gaudily painted wooden box on a stage, trying not to move a muscle and keeping my breath light and quiet. The audience can’t see me but I catch glimpses of them through tiny cracks in the wood, the stage lights reflecting in their wide eyes. It feels naughty and exciting to be in here, like playing hide and seek.

In a minute or so when my cue comes, I’ll slip off the top layer of my costume, get in position and prepare to reappear in what seems like a different outfit and from what seems like a tiny space. It’s magic. The audience applaud, delighted that they have been fooled.

When I first started working as a magician’s assistant in a late-night cabaret show in a small central-London theatre, I couldn’t have anticipated just how much it would change my performing life. Stage magic and illusion had not, unsurprisingly, been part of my training at university and drama school, but they opened up a whole new world of stagecraft, audience interaction, pacing and physicality that helped me unlearn and relearn ways to be and communicate on stage, as well as to direct and focus the attention of audiences.

More: How virtual reality, with its complex sensory tricks, takes us beyond the real world.

I was impressed by the enduring skill and beauty of traditional routines with doves, cups and balls, and linking rings, and was shocked at the boldness of obvious moves. The audience was not only complicit but vital in making the magic happen through a connection that felt almost childlike at times: they wanted to believe the impossible but were also eager to know how it was done. Chatting in the bar afterwards, they always came up with ideas that were much more ingenious and complicated than the often banal reality.

Creating a rapport

The methods of magic really should be kept secret so as not to break the spell and spoil the game. Throughout my years as part of a double act I was only told the techniques to tricks on a need-to-know basis - the more I knew, the harder I found it to ‘sell’ a trick unironically on stage – so there were some things we did that I was happy to be fooled by, as I knew the truth would be disappointing!

As the assistant in a comedy magic show, the constant direct engagement with the audience and use of audience volunteers was a total departure from my previous experience as an actor. I learned through trial and error to develop a sense of who might play along if invited on stage.

You need to take charge and create a rapport quickly. I found the best way to control a volunteer was to ‘claim’ them with an item of clothing, a prop or an accessory to make them immediately part of the onstage world and discourage them from deliberately trying to pull focus. In a traditional male-female double act where the man is considered to be the magician and the woman only a decorative mover of props, there is enormous scope for misdirection and playing with presence and status.

Spontaneity, subversion and sound effects

Despite the fact that she is often absolutely key to the success of the trick in more ways than one, the magician’s assistant is rarely presented as having creative agency of her own. This is often reinforced visually and verbally, with hyper-feminised and sexualised costumes that draw the eye to her body rather than her face. Instead of direct speech, she communicates with the audience through eye contact, gestures and mime, meaning they don’t look to her for detailed information about what is going on as the narrative of a trick progresses.

I found that this unexpectedly opened up a world of opportunity to play and learn. Just because the assistant doesn’t speak, it doesn’t mean she is uncommunicative. She can use different areas of the stage to make the audience move their heads as well as their eyes away from what the magician is doing, and she can create distractions and reactions that seem entirely spontaneous, despite being meticulously timed and planned.

The magician’s assistant is rarely presented as having creative agency of her own.

Sometimes she needs the audience to notice her actions and at other times she absolutely needs them to ignore her. The latter can be achieved through non-verbal signals such as subtle changes in body language, posture and gaze.

I was surprised to find that many magicians choose not to speak on stage, instead relying on mime and music to tell the story of a trick. Music is a shortcut to producing an emotional connection with audiences and shaping their expectations in many different ways.

Funny sound effects create shared moments of laughter and the use of familiar tunes signals to the audience when reveals will happen and how they should respond. Underscoring (playing music quietly as a trick unfolds) helps to create rhythmic moments that build tension and mimic what might be done elsewhere with language – for example, the rule of three can apply to reveals timed to music cues to make them as successful as spoken comic punchlines.

A comedy magic show might not seem like the perfect place to challenge the lazy sexism of traditional performative presentations of gender onstage, but in my experience a female assistant can send up and subvert the stereotypes by encouraging the audience to laugh at them.

This can be done most obviously through switching roles, but this is harder than it sounds, as the practicalities of performing stage tricks are also gendered in subtle and not so subtle ways. Magic instruction books, DVDs and downloads invariably feature a male demonstrator and methods are created with male clothing and accessories as standard tools – so tricks and methods need to be adapted before they can be used on stage by female magicians.

Now that I work as a solo act, I know that my time as a magician’s assistant gave me the confidence to emerge on stage as not just a surprise or a novelty, but as a skilled performer capable of making the magic happen herself.

About the author

Naomi Paxton

Comedian and theatrical academic Naomi Paxton researches the history of suffragists and the theatre, and appears as alter-ego Ada Campe, who has been nominated for Best Variety Act at the Chortle Awards 2019. She is also the reigning winner of the New Act of the Year at the NATYS and the Leicester Square Theatre Old Comedian of the Year.