The character of Sherlock Holmes, famous for drawing his conclusions from detailed observations, was inspired by a real-life doctor. But while doctors’ diagnoses use similar methods to detectives, the clues they spot and the verdicts they reach may be less clear-cut.

Mrs Agwu’s face is expressionless – there are no diagnostic clues at first glance. Her posture is stooped, a question mark of sorts. The sole of her right shoe is scuffed. Her husband has a black eye.

The diagnosis is Parkinson’s, I realise. Her muted facial expression and stooped posture are characteristic. She has been dragging her foot, hence the scuffed shoe. Mr Agwu has a black eye because his wife inadvertently lashes out at night – a dramatic sleep disturbance is another feature of the condition.

Doctors and detectives seem to approach our mysteries similarly – we each spot inconsistencies, form hypotheses, reason logically, and reflect deliberately. We deduct and decode signs and symptoms (or clues). But on deeper inspection, how much truth is there in the comparison? The world of one literary detective, Sherlock Holmes, might just hold the answer.

His creator, Arthur Conan Doyle, a doctor himself, based many of Holmes’s methods on those of Joseph Bell, a professor of surgery and one of Conan Doyle’s tutors at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.

More: How lowering testosterone affects the male body.

Bell’s infamous diagnostic skills were once described by a medical student of his: “‘What is the matter with this man, eh?’ Then flashing a signal to one particular student with those piercing eyes, Dr Bell would indicate he should pronounce the diagnosis. ‘No, you mustn't touch him. Use your eyes, sir, use your ears, use your brain, your bump of perception, and use your powers of deduction.’”

In ‘A Case of Identity’, Holmes stresses the importance of sleeves and the great issues that might hang from a bootlace. Here, he deciphers the occupation of a “fellow-mortal” (from ‘A Study in Scarlet’): “By a man's fingernails, by his coat-sleeve, by his boot, by his trouser-knees, by the callosities of his forefinger and thumb, by his expression, by his shirt-cuffs – by each of these things a man’s calling is plainly revealed.”

Forensic photography

Incident_0864. Image_053. 2019-04-24 10.12am.

Blood spatter on floor inside front door.

Technique: Conventional photograph of blood spatter with linear and colour scales.

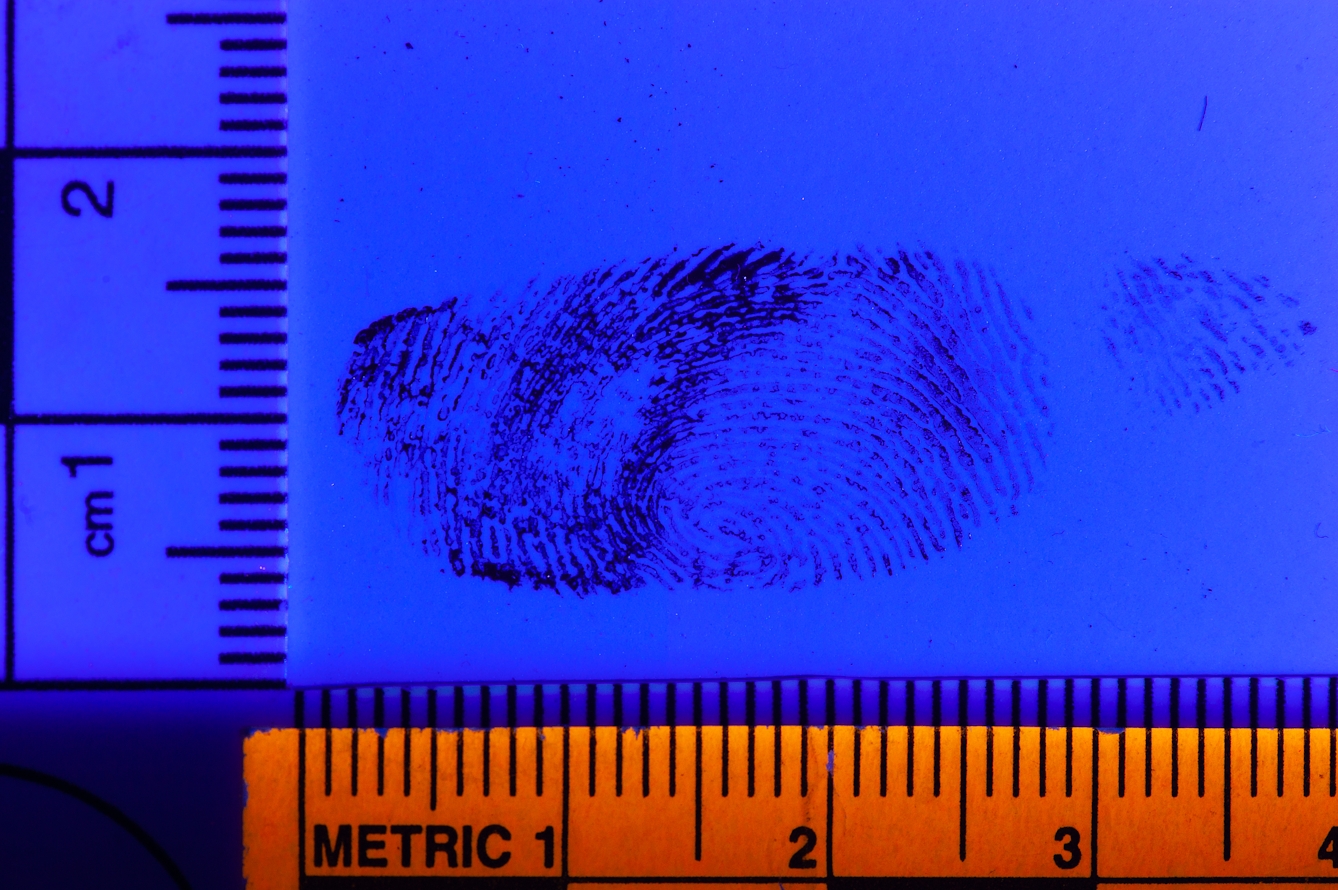

Incident_0864. Image_109. 2019-04-24 11.33am.

Fingermark in blood located on living-room table.

Technique: Photographed using deep blue light to improve contrast of blood.

Incident_0864. Image_235. 2019-04-24 12.02pm.

Fingermark located on bathroom doorframe.

Technique: Fingermark is visualised/developed with black powder and photographed with diffuse white light.

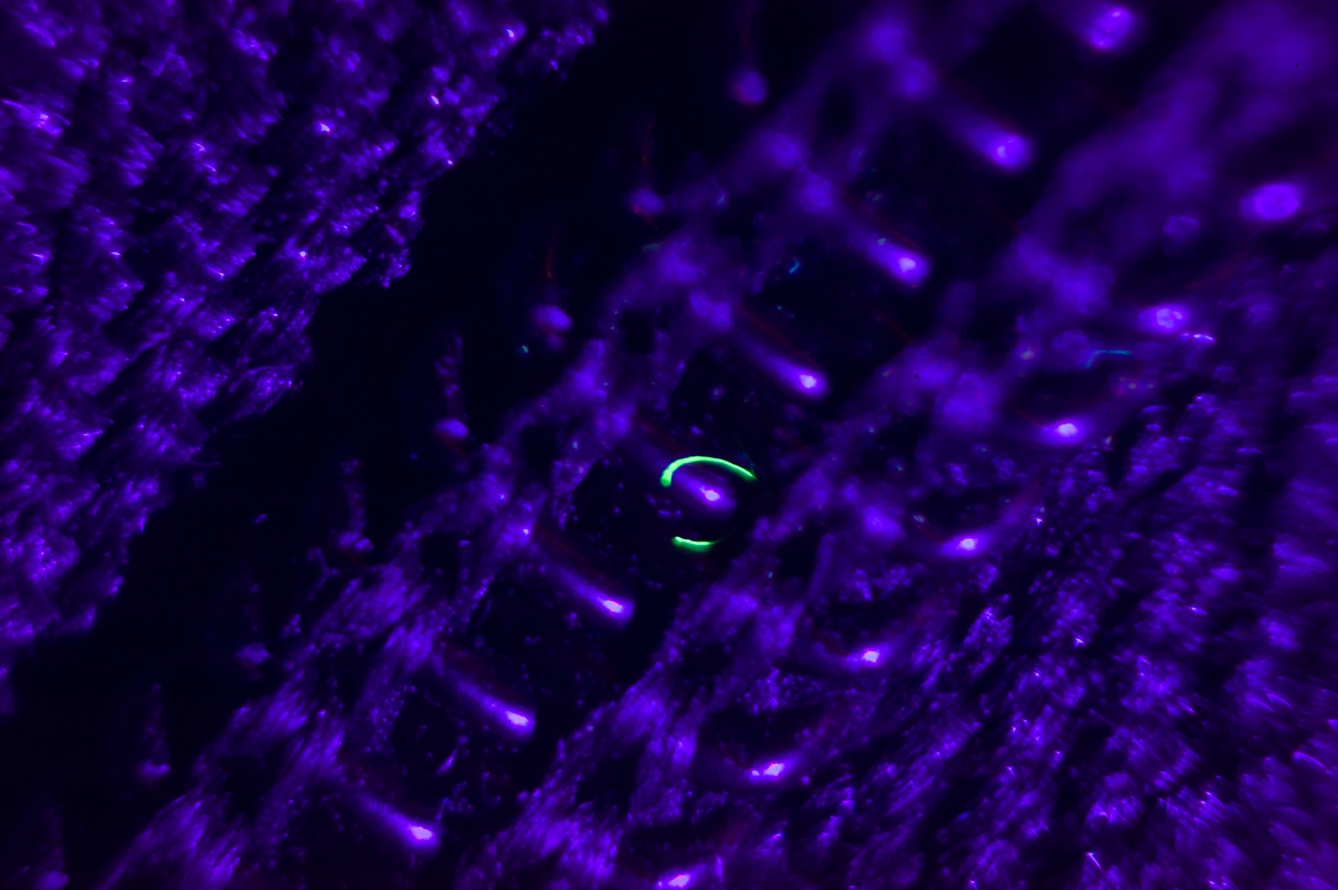

Incident_0864. Image_389. 2019-04-24 1.12pm.

Textile fibre caught in the zip of coat.

Technique: Photographed through low-power microscope, a textile fibre fluoresces brightly under UV light.

An eye for detail

Such subtleties lead doctors towards diagnoses, too. Pitted nails (these look like the surface of a thimble) are sometimes seen in psoriasis, for example. Mees’ lines (transverse white bands across the nails) are associated with arsenic poisoning, heart failure, renal disease and chronic infections.

Absence is as telling as presence. Mrs Agwu’s right leg is not weak – this likely excludes a stroke (another explanation for a scuffed shoe). In ‘Silver Blaze’, Holmes notes the curious incident of the dog in the night-time: the dog did not bark, thus it must have recognised a shady midnight visitor.

It’s tempting at this juncture to rush towards a conclusion, but Holmes guards against this: “It is a capital mistake to theorise before you have all the evidence.” If a letter from Mrs Agwu’s GP outlined her slowing down and blank expression, I might consider a diagnosis of depression, testing this hypothesis by asking questions about her mood.

There’s danger in this hypothetico-deductive approach, akin to the crime of Procrustes – the inclination to fit the facts to our opinions instead of our opinions to the facts (Procrustes was a figure from Greek mythology who offered unwitting travellers a bed for the night. Little did they know he would stretch them or amputate their legs to fit the bed). In being welded to this possibility of depression in Mrs Agwu, I might miss the clues pointing towards her Parkinson’s.

Holmes usually draws upon abduction rather than deduction: starting from observations or the known facts, then deriving their most likely explanation. Abduction entails working backwards to a probably or possible conclusion.

In ‘The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle’, Holmes sees a cast-off hat and concludes that the man is highly intellectual (the hat is large – “a man with so large a brain must have something in it” – we now know this has no scientific basis, sadly) and experiencing a decline in fortunes and foresight indicating “some evil influence, probably drink”, since the expensive hat has entered a state of disrepair.

Holmes reasons, from hairs on the hat’s lining, that the man is middle-aged, with recently cut, grizzled hair, which he anoints with lime-cream. “It is extremely improbable that he has gas laid on in his house,” he concludes, given the presence of tallow stains.

Admittedly, one recent critic described this hat trick as “barely a half-step from parody”. In my view, though, Holmes was no ordinary detective, just as Joseph Bell was no ordinary doctor.

Forensic photography

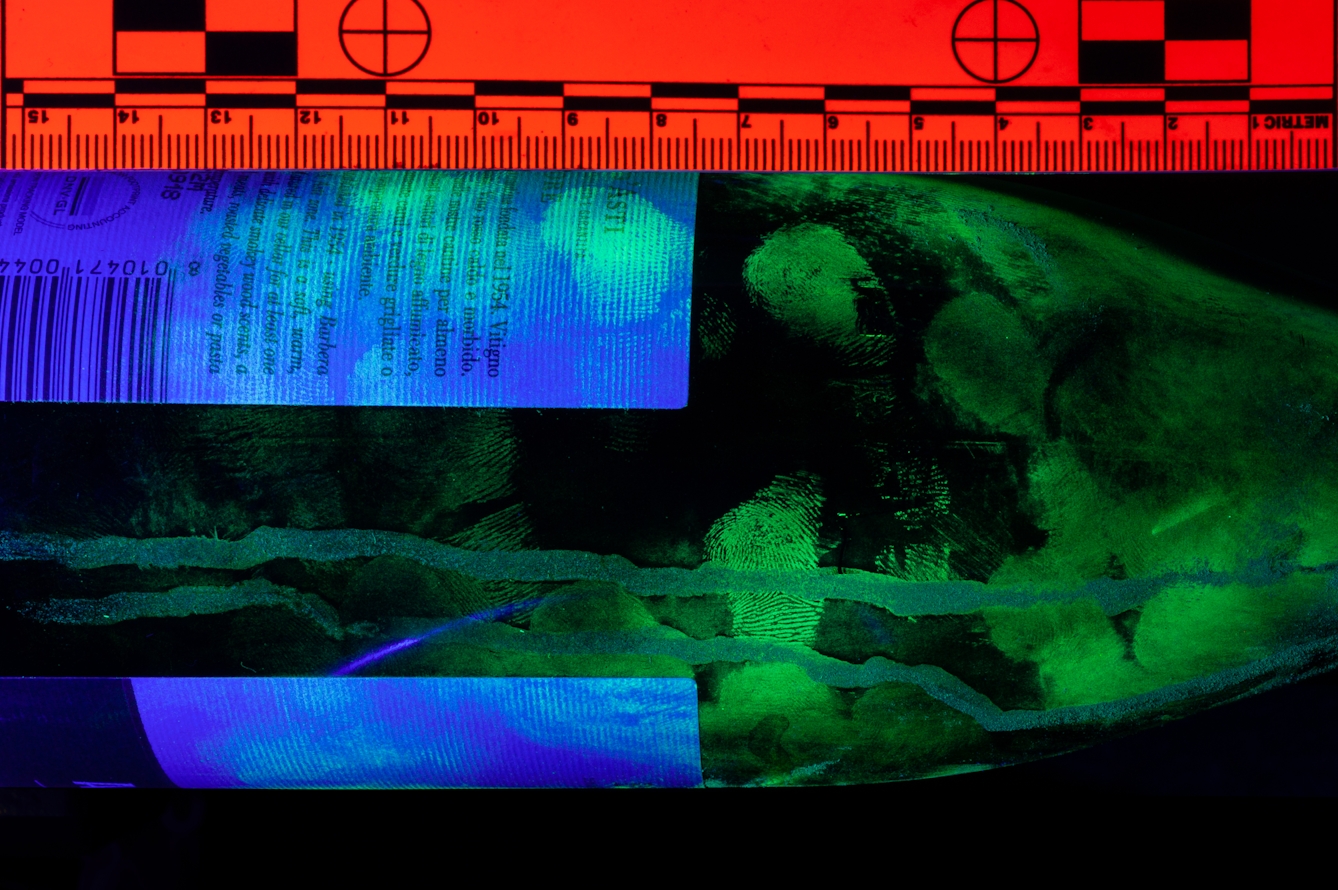

Incident_0864. Image_498. 2019-04-24 2.04pm.

Wine bottle found in living room covered in fingermarks.

Technique: Photograph of fingermarks visualised with magnetic green fluorescent powder under UV lamp.

Incident_0864. Image_582. 2019-04-24 3.12pm.

Wine glass bearing fingermarks and traces of lipstick.

Technique: Photographed with hard, directional light, revealing lip mark and untreated fingermarks.

Incident_0864. Image_633. 2019-04-24 4:03pm.

Sole of a training shoe found in the living room.

Technique: Long-exposure photograph of luminol reaction, revealing extensive blood traces on sole of training shoe.

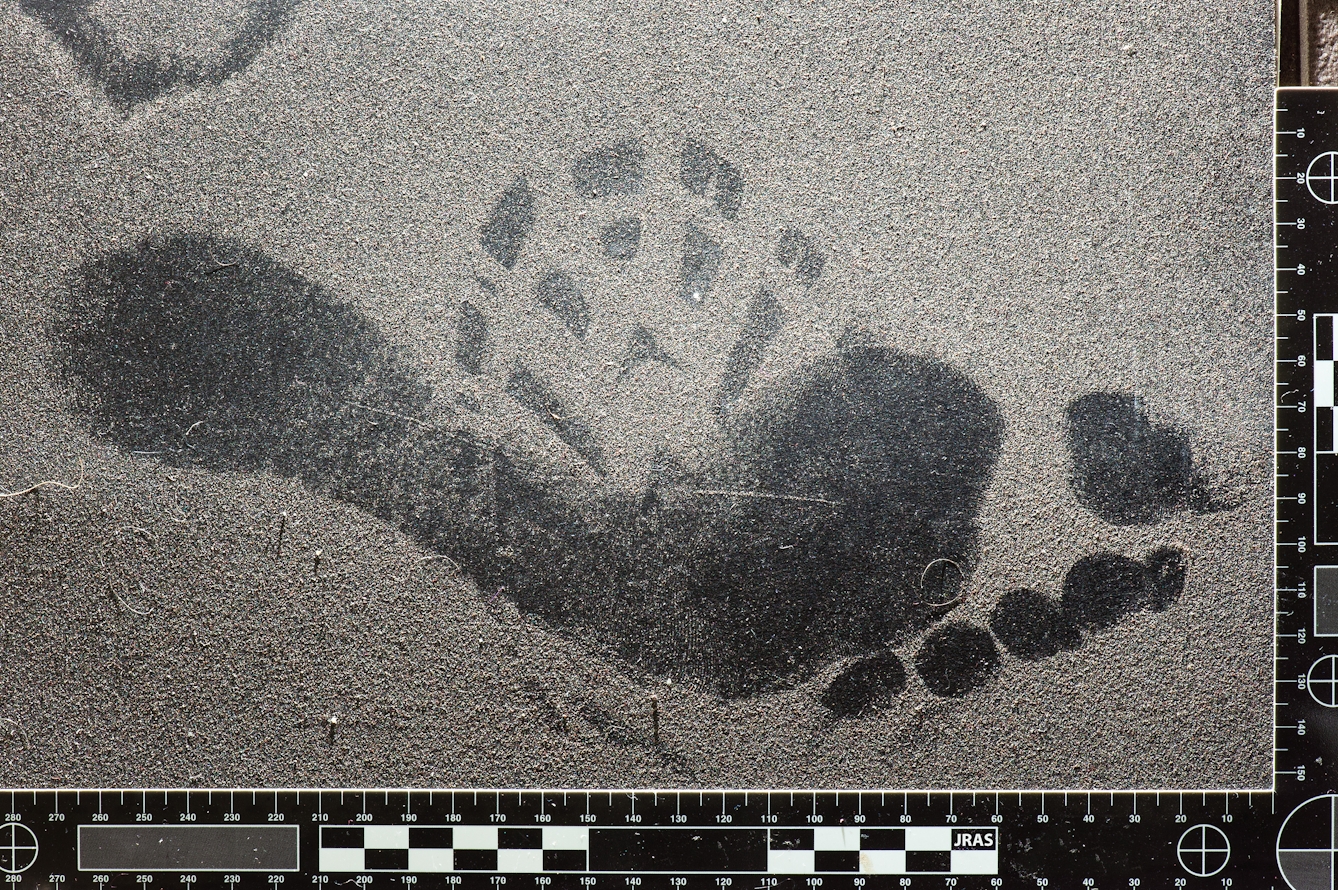

Incident_0864. Image_747. 2019-04-24 5.41pm.

Footmark and footwear mark found on bathroom floor.

Technique: Photographed with oblique lighting, revealing marks in dust. Close examination suggests the footwear mark was deposited before the bare foot mark.

Arguing backwards

This abductive approach is the most commonly used investigative logic used in real-life murder investigations and is also often used iteratively in medicine, where we argue backwards from symptoms (the effects) to disease (the cause). Here’s an example:

Premise 1: Most people with chronic untreated gout have tophi (crystals of uric acid, usually in or around joints).

Premise 2: This patient has tophi.

Conclusion: This patient probably has chronic untreated gout.

Observations made and reasons reasoned, it’s time to consider all potential causes or suspects before reaching a final conclusion (termed differential diagnosis in medicine). “One should always look for a possible alternative, and provide against it. It is the first rule of criminal investigation,” says Holmes. Inspector Stanley Hopkins is also schooled by Holmes, who tells him in ‘The Adventure of Black Peter’: “You were so absorbed in young Neligan that you could not spare a thought to Patrick Cairns, the true murderer of Peter Carey.”

Yet, for all these parallels, differences abound between the crime scene and clinic consultation. We regularly face messy contradictions and uncertainties that are absent from the Holmesian universe.

“When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth,” Holmes says, but in medicine, there is inevitably more than one improbable solution, and more than one that might be true. Two people with the very same disease might present with different symptoms. Two people with identical symptoms often have different disorders. Many disorders have yet to be elucidated.

Doctors also cannot work on logic alone. Hermeneutics matter – the interpretation of text: the stories of our patients, their lived experience of illness, and our diagnostic tools. So does semiotics – the doctrine of signs: the bull’s-eye rash of Lyme disease or the tiny Koplik spots of measles inside the mouth.

In some cases, the methods of doctors more clearly reflect those of other literary detectives, who go beyond the singular theory or neat resolution. The investigative approach of William of Baskerville (a Franciscan monk in Umberto Eco’s ‘The Name of the Rose’) seems more closely attuned to medical diagnosis, what with its multiple layers of reasoning and “complex of motives, coincidences, and perspectives”.

But none of this should underplay the strong Holmesian parallels with medicine. I sense, as I examine Mrs Agwu in a hospital just a few miles from Baker Street, that there are more similarities than differences between Holmes’ detecting skills and our doctoring ones. That much, Holmes might say, is elementary.

About the contributors

Jules Montague

Doctor Jules Montague is a former consultant neurologist, and the author of ‘The Imaginary Patient: How Diagnosis Gets Us Wrong’ (Granta 2022). It explores how the practice of diagnosis is tainted by the forces of imperialism, politics, discrimination and Big Pharma. She also writes about health and science for the Guardian, the BBC, and New Scientist. Her first book, ‘Lost and Found: Why Losing Our Memories Doesn’t Mean Losing Ourselves’ (Sceptre, 2018), explores what remains of the person when the pieces of their mind go missing.

John R A Smith

John Smith is a forensic imaging specialist who spent ten years working for the UK’s major forensic science providers before being appointed in 2007 as a senior lecturer in imaging science at the University of Westminster. His independent work includes consultation on forensic imaging processes, casework, lecturing and training. He enjoys providing lectures and courses to a variety of higher-education Institutes and forensic practitioners.