Living thousands of miles from her mother, Sandy Di Yu found that their approaches to the pandemic were markedly different. But over the months, and many calls and messages, Sandy grew to understand and embrace her mother’s point of view.

The newfound germaphobe in me winces at memories of late January 2020, when I’d sit next to strangers on trains with bad coughs, and snotty tissues overflowing their pockets. Every weekday morning of that drizzly, mild winter, I’d make my commute to London Bridge, squeezed together in forced proximity to my fellow commuters. In a city of more than eight million people, where isolation plagued so many, proximity might not replace intimacy, but I often thought that it could be a passable simulation.

On 25 January I messaged my mum to wish her a happy Chinese New Year. Her message back was the first time we spoke about the virus. “Happy Chinese New Year to you too! We did not go out to a restaurant this year due to the recent viruses from Wuhan.”

I rolled my eyes and ignored the last part. In January, the virus wasn’t yet real, too far removed from the UK and any major English-language news outlets. But my mother, based in Canada, mostly watched Chinese news channels. For her it was already a pandemic.

Trying to blend in

I call her both Mother and Mum, but she’s gone by many names, some of which I’ve since retired: 妈妈, 娘, Mama, Mommy, Mom... ‘Mother’ was from residual teenaged habit, a joke that stuck, a way to withhold intimacy and an attempt to evade her control with overt formality. ‘Mum’ was from bingeing British television.

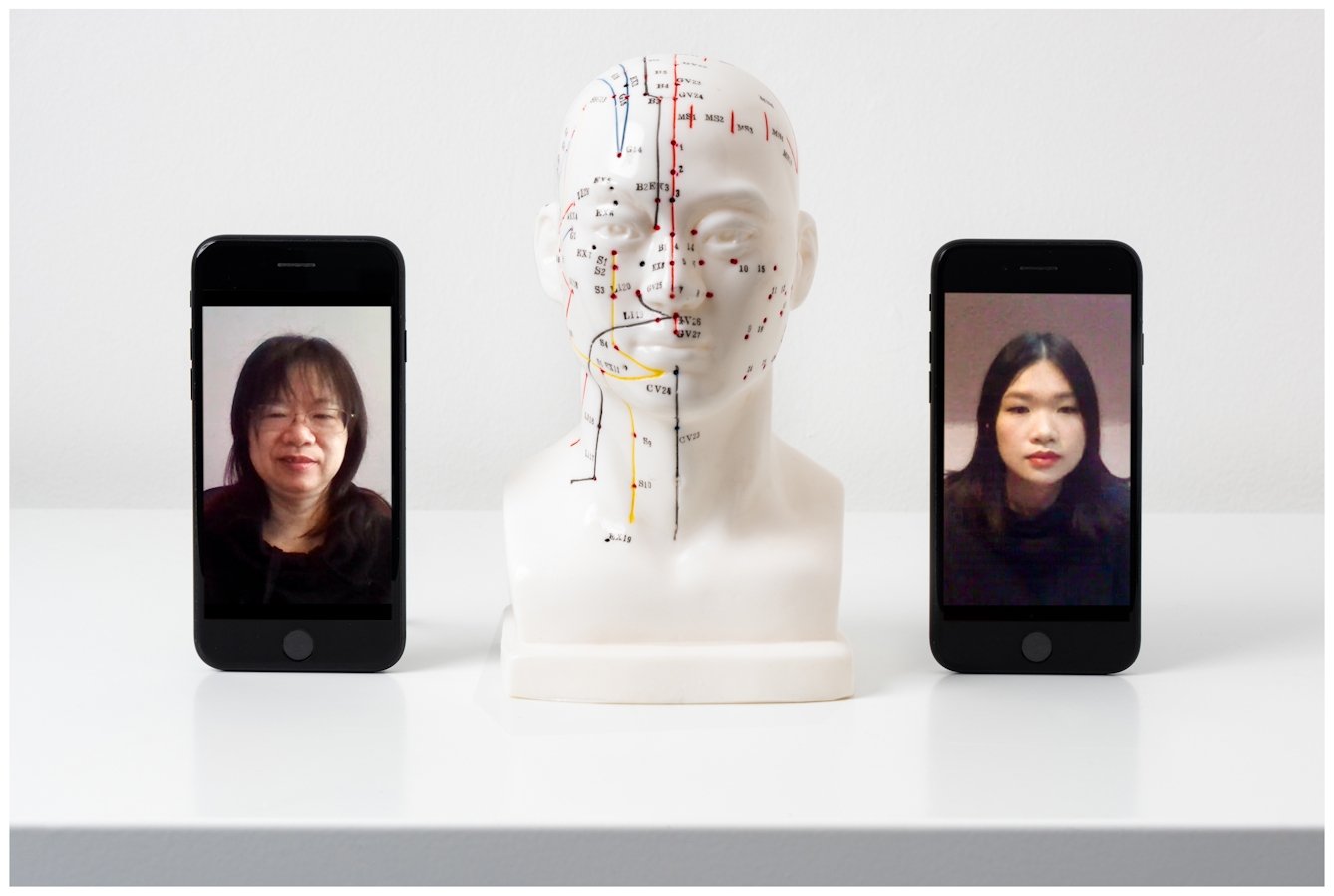

My relationship with her was fraught with disagreements when I was younger, as is typical with the dissonances created between immigrant parents clinging on to their cultural identities and immigrant children trying to forge new ones. But while other Chinese parents took up ‘normal’ professions like accounting and teaching, my mum was a practitioner of Traditional Chinese Medicines, a vocation that paraded around its foreignness without any hint of self-consciousness, much to my perplexity.

Like many teens, I was naturally really embarrassed all the time, so the weird-smelling medicines she brewed and the unabashedly un-Western ideologies she espoused alienated me further from her motherly care.

“While other Chinese parents took up ‘normal’ professions like accounting and teaching, my mum was a practitioner of Traditional Chinese Medicines.”

I told her she was making a big deal out of nothing... and that wearing a mask would be more dangerous than not wearing one.

It didn’t matter how much I resisted or how far away I moved. Mothers will always find a way to impose concern. Since that first mention of the virus, every day she implored that I bought myself a face mask, that I stay home whenever I could and to go grocery shopping at off-peak hours in order to avoid crowds. I told her she was making a big deal out of nothing, that I couldn’t just not go into work because of her worries, and that wearing a mask would be more dangerous than not wearing one.

East Asians were already being confronted with varying degrees of assault in those early days, and while I couldn’t hide my ethnicity, I could try and blend in, make myself appear less foreign by way of dress and mannerisms. My mother didn’t understand, immune as she was to ethnicity-based self-doubt. I envied her, but I also worried about her just as she did me. We argued about this a lot, with our ideas of self-preservation deviating by a broad stroke.

Contaminated with metaphor

Susan Sontag’s 1978 ‘Illness as Metaphor’ explains how the metaphorical prowess of a disease comes from its depth of mystery. In the age of information and post-Enlightenment rationality, nothing remains a universal mystery for long. But in the earlier parts of 2020 Covid-19 was still mysterious, mutating into racially coded metaphors of otherness and uncleanliness.

It paralleled metaphors of the Middle Ages where, as Sontag notes, illness was “firmly tied to notions of moral pollution”, where those experiencing disease either in themselves or as a spectator “invariably looked for a scapegoat external to the stricken community”. In February of this year, the UK wasn’t yet explicitly stricken by the virus, but the scapegoat was clearly marked. Then, I was more frightened of the metaphor than the illness.

“My mother didn’t understand, immune as she was to ethnicity-based self-doubt. I envied her, but I also worried about her just as she did me.”

Towards the end of February I developed a tickle in my throat, which turned into an unrelenting cough followed by extreme fatigue, body aches, loss of taste and high fever. Looking back now, I’m almost certain this was Covid-19, but at the time I was just annoyed I had the flu. Bedridden, I willed myself to get better.

My mum messaged me every few days with news articles about coronavirus as death tolls started to mount in parts of the world less alien to the UK. I didn’t tell her I was sick, as it would be pointless to worry her. In the midst of a fever-induced existential crisis, I lamented how terribly clichéd it would be if I died of this virus, and how sad Mum would be, especially after her pleas for me to wear masks and avoid crowds.

I got better within two weeks, and while there were probably a number of factors that favoured my health, I secretly thought my quick recovery was at least in part due to spite.

Cultivating equilibrium

I eventually told my mum that I had been sick, at which point she called me, panicked, even after I explained that I recovered ages ago. Lockdown in both the UK and Canada had begun, and we called each other more frequently. We spoke candidly about racial violence for the first time in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement, and earnest conversations took the place of our usual disagreements.

Everyone was learning how to operate under new circumstances, and the metaphor around the virus started to disperse as its mystery dissipated. Even so, there seemed to be another metaphor brewing on the cusp of recovery.

During this time of mid-lockdown boredom, I began immersing myself in literature about Traditional Chinese Medicines, possibly due to my recent guilt in shirking unsolicited motherly advice.

“During this time of mid-lockdown boredom, I began immersing myself in literature about Traditional Chinese Medicines, possibly due to my recent guilt in shirking unsolicited motherly advice.”

I learned how these types of medical practices take on a holistic approach to health and wellness, where a balance must be struck not only within one’s body but also in equilibrium with the environment and society as a whole. I began to appreciate these practices as a philosophy that extends to planetary modes of survival, far beyond the acrid, murky concoctions that taint my early memories of medicine.

Susan Sontag’s metaphor was one that suggested “a profound disequilibrium between individual and society, with society conceived as the individual’s adversary”. As Covid-19 becomes understood in terms of protecting the vulnerable of society through acts of distancing and face coverings, what emerges is a new type of metaphor, where individual health is cultivated through equilibrium with society and environment. We wear masks not to individuate, not to mark ourselves as a carrier of disease or out of fear of the contaminated, but to protect the collective. Distance becomes care.

At the end of June, I gave my mum the news that I was engaged. I expected something akin to jubilation, but all I got was underwhelming, sombre congratulations. I asked her why she seemed sad about what was supposed to be happy news.

“I’m not sad about you getting engaged,” she replied. “It’s just… I guess this means you’re really not coming back?”

Swallowing the bubbling guilt and reminding myself that she too moved halfway around the world once, four-year-old me in tow, I told her I didn’t know. What I did know, what I’d learned since January, was that proximity did not beget intimacy and that, despite government-mandated distances, we’ve managed to become closer.

About the contributors

Sandy Di Yu

Sandy Di Yu is a researcher, writer and artist currently based in London, UK. Originally from Canada, she obtained an MA in contemporary art theory from Goldsmiths, University of London in 2018 following her Bachelor of Fine Arts in visual arts and philosophy. Her current research interests include the dissolution of temporality in digital systems and transcultural depictions of health.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.