In the second part of ‘Native Americans Through the 19th-century Lens’, we delve deeper into the legacy and impact of photographs that make for some uncomfortable viewing.

Native Americans and the dehumanising force of the photograph

Allison C Meier

- Story

Photographs, and how people are presented in them, can impact health and survival. In the 19th century, such photographs and artistic depictions of indigenous people as primitives left behind by modernity – or savages disrupting progress – reinforced popular ideas about manifest destiny and the federally enforced displacement of tribes to reservations.

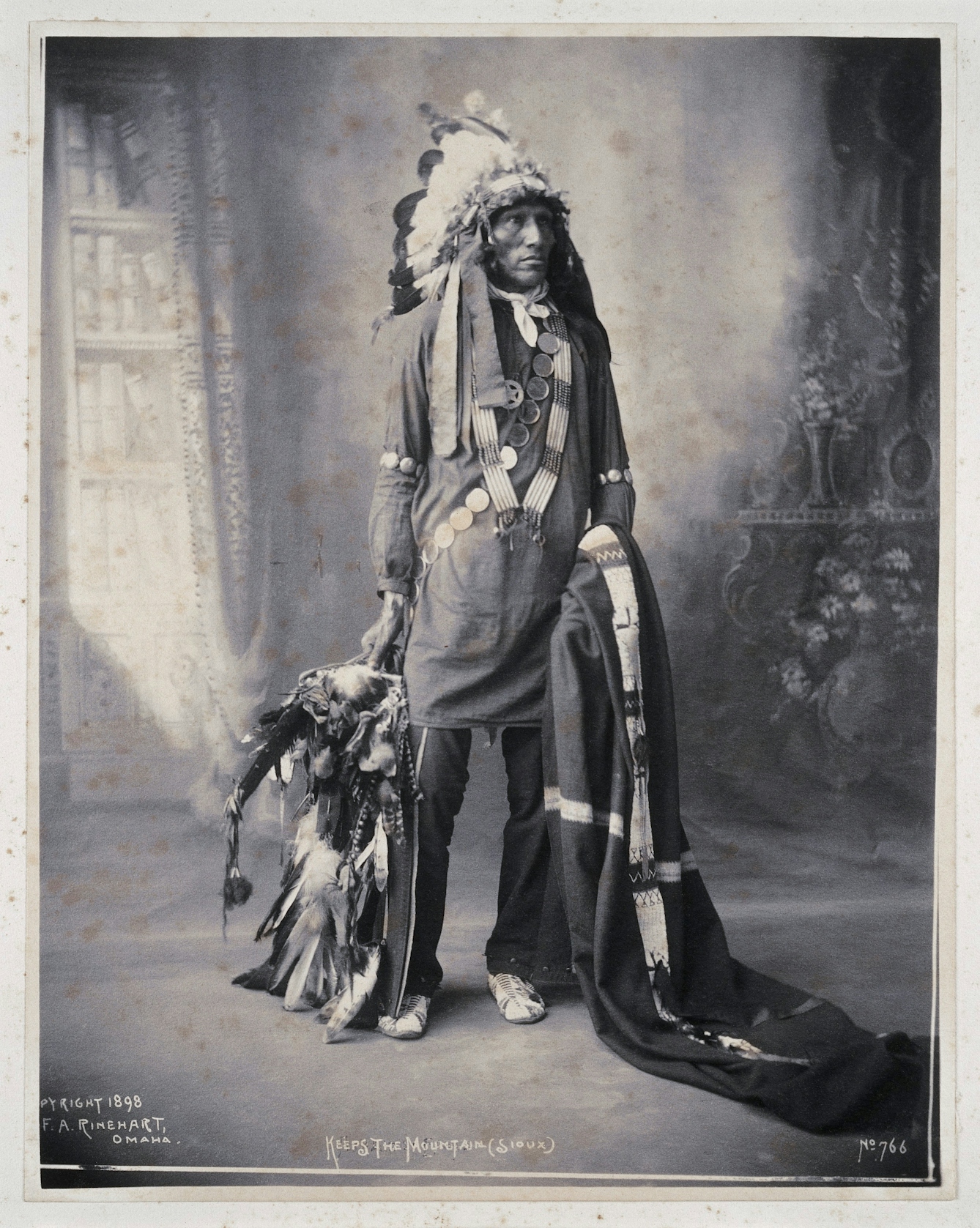

Portrait of Keeps the Mountain, a Sioux Indian. Frank Rinehart, 1898.

Frank Rinehart’s studio portraits of the Indian Congress at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska, in many ways reflect these beliefs, not least in their juxtapositions of ceremonial and traditional dress with the painted studio backdrops of bookshelves and flowers.

Yet these photographs of representatives from more than 30 gathered tribes also have a sensitivity lacking in other depictions of Native Americans from this era. Nevertheless, they were created as a commodity, sold to white visitors at the world’s fair.

In the 2005 book ‘Beyond the Reach of Time and Change: Native American Reflections on the Frank A Rinehart Photograph Collection’, Simon Ortiz writes:

“Whether he wanted to or not, the real and actual Indian vanished into the image contrived by non-Indian interests, since he became, in some sense, acceptable then ‘as an Indian’, albeit an Indian fashioned, styled and – even literally – costumed (for example, photographic studio props were used by photographers such as Rinehart and Edward Curtis) so that he could be identified as nothing but an Indian.”

‘The Vanishing Race’. Edward Sheriff Curtis, 1904.

Curtis, like Rinehart, believed he was photographing a rapidly disappearing people. In fact, one of his most famous shots is the 1904 ‘The Vanishing Race’, showing a group of Navajo riding away from the camera into a shadowy distance. His 20-volume ‘The North American Indian’ so instilled this idea as fact that into the 21st century we can find headlines over his images about ‘lost tribes’.

A ‘Yebichai Sweat’ Navajo medicine ceremony with three Navajos in ceremonial dress wearing masks. Edward Sheriff Curtis, 1904.

Creating a cultural curiosity

At the same time that Rinehart and Curtis were taking these photographs, anthropologists were collecting indigenous objects and artefacts, digging up graves for bones, then cataloguing these fragments in collections and museums, without taking any steps to improve the lives of the people they represented.

In the 2016 book ‘Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums’, Samuel J Redman notes:

“The campaign to preserve and collect was viewed as a race against time; bone empires benefited from this powerful sentiment by conceptualising indigenous and ancient bodies as a limited and scientifically valuable resource.”

Dance bonnet and scalplock of an Omaha Indian. Frank Rinehart, 1899.

Curiously, though, as indigenous people were increasingly considered a thing of the past, they became more prominent in visual culture, as if they had escaped their complicated bodies to become an all-American symbol. The Americans exhibition at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC, surrounds visitors with an overwhelming array of these appropriations, from street names across the country, to the Cleveland Indians’ mascot, to the Indian Chief motorcycle with its feathered headdress logo and colour options such as Seminole Cream and Mohawk Green.

A Jicarilla Indian Chief in ceremonial dress. Edward Sheriff Curtis, 1904.

Big Foot's camp, three weeks after the Wounded Knee Massacre of 29 December, 1890.

Enduring images

From photography’s first decades, it has been a visual of persuasion – something that’s easy to forget when it feels like a stand-in for our own eyes. It is interesting to compare, for instance, the reception of Curtis and Rinehart’s images with those made just years before at the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee, when the US Cavalry fired on a Lakota encampment in South Dakota, killing at least 150 men, women and children.

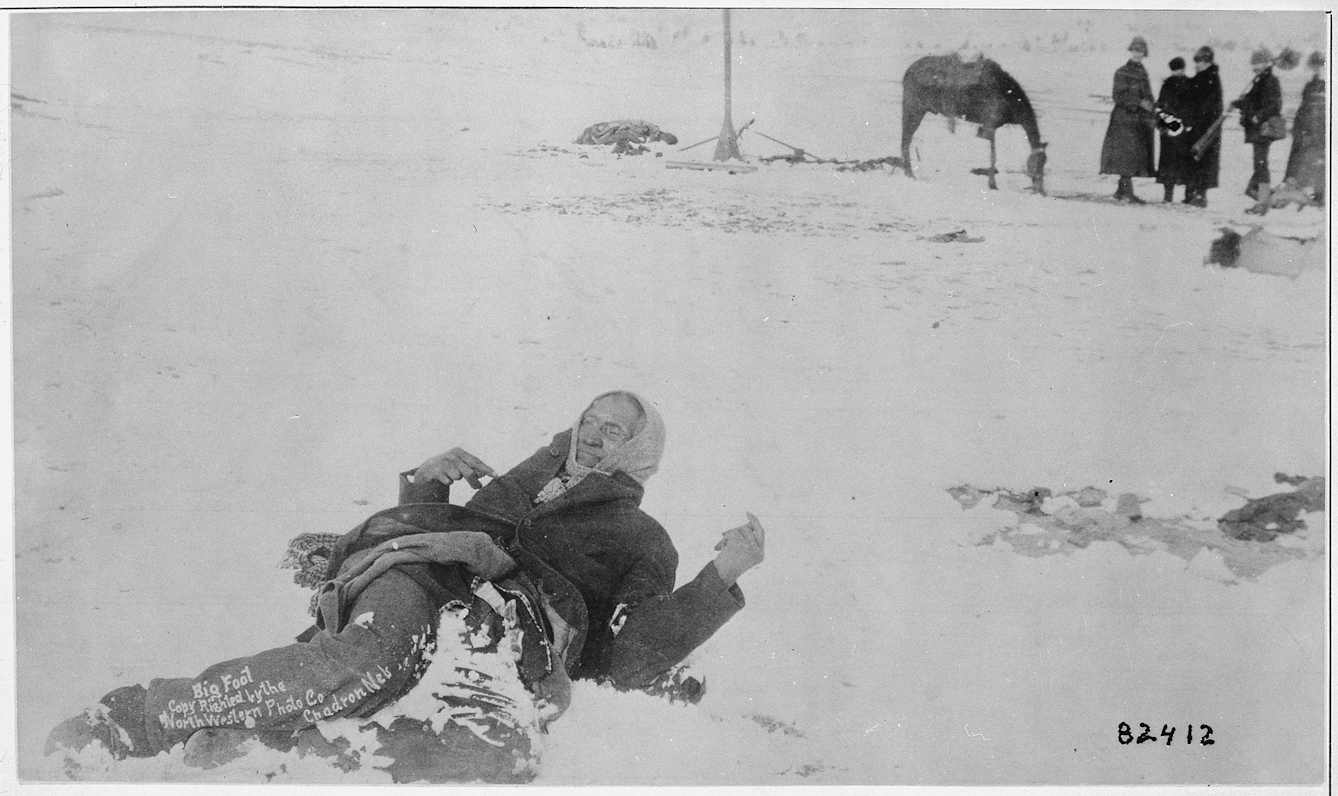

Big Foot, leader of the Sioux, who was captured at the Battle of Wounded Knee, frozen on battlefield where he died, 1890.

A photographer named George (Gustave) Trager took images of the aftermath, capturing in detail the slaughtered indigenous bodies. In 1994, Christina Klein wrote in the ‘Western Historical Quarterly’:

“[Trager’s photographs] of the dead Lakotas at Wounded Knee acted as vehicles for the very values of incorporation that somehow made logical the killing of the Lakotas. Beyond documenting the deaths of a number of Indians, these images depicted the destruction of the tribal entity. They portrayed a people shattered into isolated, individual bodies, the sense of fragmentation visually heightened by the white expanse of snow surrounding each corpse.”

Like Rinehart’s portraits, these photographs were bought and sold, labelled with Trager’s studio name neatly scrawled on the leg of the dead chief Big Foot (aka Spotted Elk) or over the burial trench. They were advertisements for the creator, not calls for empathy.

Burial of the dead after the Wounded Knee Massacre. US soldiers putting Indians in a common grave. South Dakota, 1891.

Parting shots

Photography is perhaps more dominant than ever in how it frames our understanding of the world, from the constant barrage of carefully curated social media to the coverage of disasters and war that mingle with these snaps of everyday life.

The influence of Rinehart and Curtis rippled up through film with Hollywood’s portrayal of indigenous people as primitive, yet noble, and the use of stereotypical images for sport mascots. These photographers were not necessarily intending to perpetuate stereotypes, but in presenting a living, diverse group of people as a single race that was fading, they encouraged the enduring popular perception of indigenous people as absent from contemporary American life, except in images.

About the contributors

Allison C Meier

Allison C Meier is a Brooklyn-based writer who focuses on history and visual culture. She was previously Senior Editor at Atlas Obscura and more recently a staff writer at Hyperallergic.