A yoga teacher in 1930s India inspired today’s transnational yoga with his spectacular fusion of tradition and innovation.

Yoga adapts to time and place

Words by Lalita Kaplishaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Serial

Suzanne and Alaric both practice Iyengar yoga. Alaric holds the ‘plough’ asana (posture) for the video, as Suzanne, who is also a yoga scholar, explains that Iyengar yoga is distinguished by “precision in how asana is performed”.

Ruth has also been doing yoga for many years. As she flows effortlessly through a series of moves, she says, “I practise ashtanga yoga, which is an asana-based sequence of postures – there are various different sequences.”

Experienced yoga practitioners describe their practice in terms of the system in which they trained. This is likely to be one of a handful of transnational yoga systems: ashtanga, Iyengar, Sivananda or one of their many spin-offs.

Transnational yoga systems are usually centred on a postural (asana) practice that draws on a synthesis of ancient metaphysical yogic practices, traditional South Asian physical culture and modern Western exercise systems.

Nowhere is the fusion of elements in modern yoga better demonstrated than in the method developed in 1930s India by Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888–1989).

The father of modern yoga

Krishnamacharya has been described as the “father of modern yoga” (by yoga scholar Mark Singleton in ‘Yoga Body’) largely thanks to the global success of his students. The creators of Iyengar yoga and ashtanga yoga – B K S Iyengar (1918–2014) and Pattabhi Jois (1915–2009) respectively – helped to make modern postural yoga a global phenomenon. Indra Devi (1899–2002), a Latvian-American who also trained with Krishnamacharya, popularised yoga in America with the help of celebrity Hollywood clients such as Gloria Swanson and Greta Garbo.

The record sleeve for Indra Devi's home yoga course, 1963.

Born to a Brahmin family in Karnataka in Southern India, Krishnamacharya was initiated into the culture and practice of yoga from a young age. In 1915, at the age of 27, he travelled to Tibet to study yoga with the guru Rammohan Brahmacari. He spent several years teaching and touring until 1931, when the Maharajah of Mysore invited him to teach at the Sanskrit school in Mysore. Two years later he was given a wing of Jaganmohan Palace in Mysore to run a yogasala (yoga school).

Krishnamacharya’s yoga system comprised a series of asanas joined by a repetitive linking sequence, based on surya namaskars.

Photograph of Krishnamacharya and his yoga students at the Jaganmohan Palace in Mysore, from his book 'Yoga Makaranda‘ 1934.

The Maharajah’s mandate

Maharajah Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV (1884–1940) took a close personal interest in physical education and often invited indigenous and foreign practitioners to Mysore. Among his other proteges was the bodybuilder K V Iyer, who taught in a gymnasium next to the yogasala.

Yoga was still the subject of scorn among the youth of Mysore in the 1930s (Singleton). They preferred the more fashionable and ‘manly’ surroundings of Iyer’s bodybuilding gym to Krishnamacharya’s yogasala.

Krishnamacharya worked under the personal direction of the Maharajah with a mandate to popularise yoga practice. If yoga was to compete with the theatrical masculinity of bodybuilding and other modern movements, it had to attract people’s attention.

Krishnamacharya did regular demonstrations at Mysore University to encourage students to take up yoga. The Maharajah also sent him further afield on what he called “propaganda work”, performing yoga demonstrations all over South India.

He also gave yoga classes as part of a physical education programme for the royal household, and performed spectacular yoga demonstrations at the Maharajah’s court. As a student, Iyengar recalled demonstrating asanas at the palace to visiting dignitaries, including delegates from the YMCA (Singleton).

The Maharajah even funded a silent movie for national circulation. The hour-long film shows a 50-year-old Krishnamacharya accompanied by the young B K S Iyengar ‘performing’ advanced asanas. The academic and curatorial advisor Sita Reddy has suggested that new ways of presenting yoga, such as film and photographic yoga manuals, led to new ways of perceiving yoga and ultimately to new ways of practising it (in ‘Yoga: the art of transformation’).

The need to perform a ‘yoga showcase’ might well have contributed to Krishnamacharya’s flowing style of yoga. The vinyasas (postures with linking sequences) are held for a relatively short time, in contrast with the older yoga tradition of holding a single pose for a length of time. Coordinating the asanas with counted breaths would also have helped synchronise postures in a group display.

Modern and traditional physical cultures

Physical culture had taken colonial India by storm. Military and educational institutions all over India offered a mix of indigenous and modern physical education. Krishnamacharya worked in just such an environment at the palace in Mysore, and inevitably this had an impact on his method.

Mark Singleton notes the similarity to exercise drills in a popular gymnastic system of the time, Bukh's ‘Fundamental Gymnastics’ and to Kuvalayananda’s Yogic Physical Education developed for schools.

Krishnamacharya believed that that yoga practice should be adapted to the time and place it was taught, and to the specific requirements of the student. One of his early students recalls that he was “innovating all the time in response to his students” (Singleton). He would modify his postures to suit the individual, even creating new positions when needed.

It’s no wonder, then, that Iyengar and Jois developed two very different systems that were both inspired by the same guru.

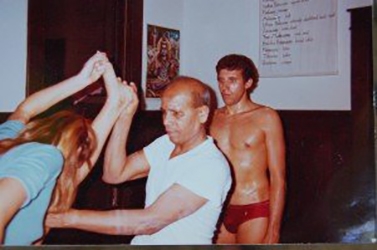

Pattabhi Jois taking a yoga class, date unknown.

Jois’s ashtanga yoga consists of three series of asanas, linked by surya namaskar-based vinyasas (transitions), performed in a counted breath sequence. Jois trained and taught at the Sanskrit school, where Krishnamacharya developed a practice suitable for larger groups of active young men like him.

Iyengar, who experienced the more personal training of the yogasala, took a different approach, discarding counted breaths and insisting on very precise asanas, each held for longer periods of time.

Orthodox yet modern

Krishnamacharya was steeped in spiritual yoga and Hindu philosophy. He was keen to give his method the authority of the ancient texts, in particular Patanjali’s Yogasutras. The Indologist Norman Sjoman, who spent some time in Mysore, noted that the palace library contained several old manuscripts about indigenous practices, including hatha yoga, which Krishnamacharya would have studied.

Krishnamacharya was selective in his use of the ancient texts, rejecting some aspects of hatha yoga where they differed from the Yogasutras, because “the main source for yoga Patanjali Darsara (Yogasutras) does not include them… it is gravely disappointing that they defile the name of yoga”. (Singleton)

A page from ‘Sritattvanidhi’, an early 19th-century manuscript in the Sarasvati Bhandar Library in Mysore Palace.

The synthesis of old and new can also be seen in the work of earlier yoga innovators such as Yogendra and Kuvalayananda because of the traditional teacher-student system of learning that they inherited.

In the South Asian tradition, knowledge was transmitted as a whole, without distinction between what was learnt from the teacher and what the student may have contributed. As such, Krishnamacharya attributed his method to his own guru and to historic texts that he may or may not have encountered, rather than to his own innovations. There was no conflict for him between the continuity of tradition and the fact that the renaissance of postural yoga was “self-consciously concerned with modernity and modernising tradition” (Yoga scholar Joseph Atler in Singleton).

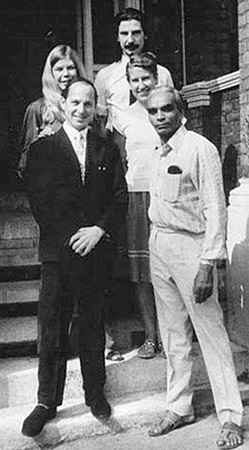

B K S Iyengar at Centre House

The process of “amalgamation and borrowing” has been a constant feature in yoga, ancient and modern. Yoga continues to transform both itself and its practitioners as new teachers develop systems of their own.

Jois and Iyengar adapted the Mysore method to meet the needs of a transnational, global community with their own mix of tradition and innovation. In the West, new schools such as Jivamukti yoga in the 1980s and power yoga in the 1990s have arisen from practitioners of ashtanga yoga and Sivananda yoga. In India, modern transnational yoga coexists alongside the continuing ancient practice of the ascetics and the even newer televised mass yoga of Ramdev.

Yoga and well-being

As Krishnamacharya said, yoga adapts to time and place. At the beginning of the 21st century, a new wave of health and well-being has given the therapeutic and health aspects of yoga a new purpose.

Eunice and James told us about the yoga therapy that they provide. In 2008, Eunice, a yoga teacher from London, volunteered with the charity We Act. She went to teach ashtanga vinyasa yoga to mainly women and children in Rwanda. Her classes supported the clinical therapy for traumatised victims of the genocide of 1994. Eunice is convinced of the therapeutic benefits of yoga for supporting people who are experiencing physical and mental suffering.

Yoga therapist James came to yoga through his own experience of stress and injury. He now works with people with severe mental health problems and believes “there’s ways that we can use movement in yoga to subtly affect people’s breathing and then their state of being”.

Is well-being a public health issue? The Centers for Disease Control in the United States see it that way. For them, well-being “integrates mental health (mind) and physical health (body), resulting in more holistic approaches to disease prevention and health”.

Many yogis around the world would say this sounds a lot like modern yoga.

About the author

Lalita Kaplish

Lalita is a digital content editor at Wellcome Collection with particular interests in the history of science and medicine and discovering hidden stories in our collections.