Surya namaskars, or sun salutations, have a long history in South Asia, but their place at the heart of modern yoga is more recent.

Sun salutations and yoga synthesis in India

Words by Lalita Kaplishaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Serial

Eunice is an ashtanga yoga practitioner. She describes the surya namaskar sequence that she demonstrates in the video as “form, connected with breath in the same sequence every time you do it”.

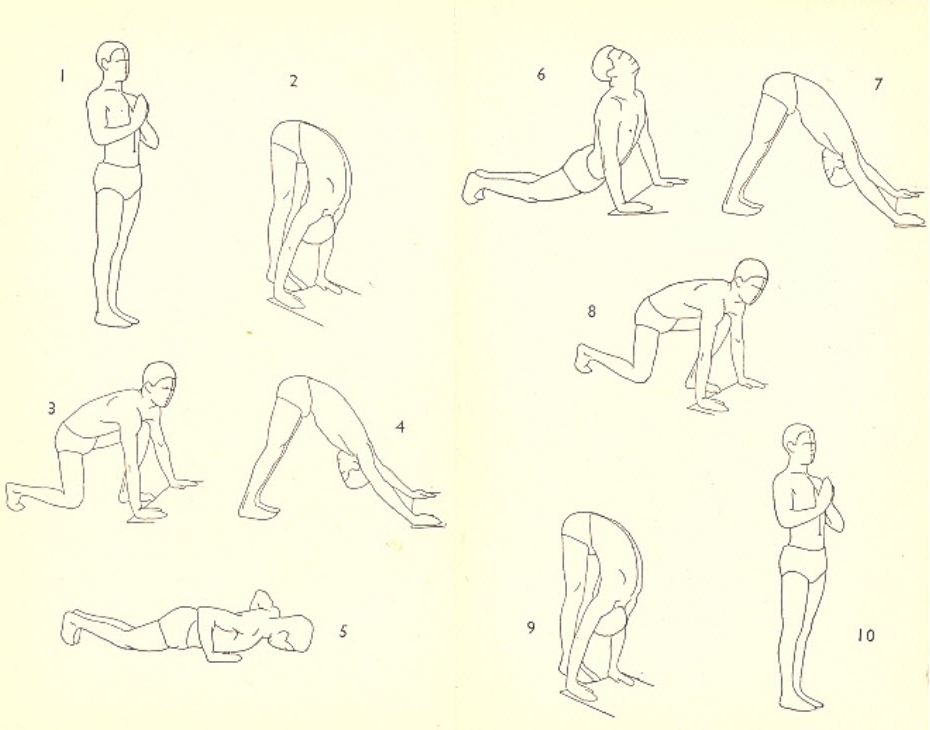

There are many variations on sun salutations or surya namaskars as a sequence of asanas (poses) in yoga. But the first systematic presentation of surya namaskar only appeared 90 years ago in Aundh (now part of the Indian state of Maharashtra), in 1938 in ‘The Ten-Point Way to Health: surya namaskars’ written by Pratinidhi Pant, the Rajah of Aundh.

The Rajah didn’t claim to invent surya namaskar: “What we give here is in fundamentals the age-old method of performing surya namaskars, and the one followed by our revered father the late Rajah of Aundh. For 55 years he did these.” He simply, “developed and changed it in accordance with modern science… and experiment by ourselves in person” (Pant, 1938).

Sun salutations were indeed an ancient tradition, originally thought to have been purely incantations to the rising sun. The poses themselves are similar to traditional martial arts exercises called dands and jors. The Rajah, who was also a bodybuilder, notes that the traditional ‘pahilwan’ or wrestler would have used such exercises to build strength, but excessive overuse was not healthy.

The ten postures in the Rajah of Aundh's surya namaskar sequence, from his book 'The Ten-Point Way to Health', published in English in 1938.

The Rajah of Aundh’s sequence of poses is designed to be repeated in cycles, accompanied by rhythmic breathing. It also requires the repetition of the different names of the sun and Vedic hymns. Pant explains that this is because “the functioning of the body is not complete if the vocal cords are left silent”, and “vibrating extends their influence… to every corner of the body”. For non-Hindus he offers a secular sequence of accompanying mantras: “om, hram, hrim, hrum, hraum, hrah”, because these sounds “are too valuable in their physical effect to be left out”.

'The Ten-Point Way to Health’ never describes surya namaskar as yoga. But the Rajah did a lot to promote it as a physical education programme in the schools of Aundh.

The perfectly developed man

The bodybuilder K V Iyer was a physical culturist who developed his own system of bodybuilding, incorporating hatha yoga and surya namaskars for fitness and body conditioning, along with European techniques. He set up a series of gymnasia and a centre in Bangalore offering bodybuilding and training.

Cover of 'Perfect Physique' by K V Iyer, 1936.

During the 1930s, Iyer appeared in international physical culture magazines, often in classical Greek poses. He was an admirer of Sandow, and later corresponded with another celebrity bodybuilder, Charles Atlas. Never modest, Iyer claimed that he was “India's most perfectly developed man” (Singleton).

Iyer was an avid practitioner of hatha yoga, which he described as “an ancient system of body-cult... [that] had more to do in the making of what I am today than all the bells, bars, steel springs and strands I have used”.

Iyer published his own booklet on surya namaskar in 1937, but like the Rajah of Aundh, he never described surya namaskar as part of yoga.

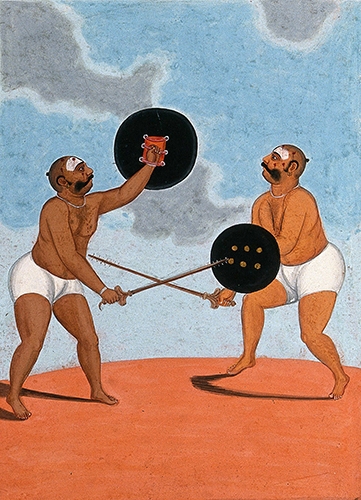

While international imports such as Eugen Sandow's bodybuilding and gymnastic-style exercise systems were influential, for men such as Iyer, indigenous practices such as wrestling, kabaddi, yoga, mallakhamba and martial arts such as lathi were equally important.

Traditional sports and martial arts

Traditional wrestling. Kalighat painting.

Traditional acrobats. 19th-century watercolour.

Acrobats described as "rope dancers and tumblers", 1815.

A game of the traditional contact sport of kabaddi. Late-19th or early-20th-century photograph.

The mallakhamba team of the Bombay Sappers.

Demonstrating the single-pole variation of mallakhamba.

A game of lathi khela, traditionally played in Panjab and Bengal.

A 19th-century painting described as two wrestlers performing traditional martial arts.

The South Indian martial art of kalaripayattu.

Building national pride

The international physical culture movement, with its promise of a new masculinity and national status through physical self-improvement, had a particular resonance in colonial South Asia.

Lord Baden-Powell described the colonial task in British India as “that great work of developing the bodies, the character and the souls of an otherwise feeble people” (Sen, 2004). Such rhetoric of cultural, moral and physical degeneracy had been internalised by the native populations after centuries of colonial rule and an anglicised educational system.

As the independence movement grew in colonial India, it became a matter of national pride to present South Asian (male) bodies as strong and powerful, and hence able to challenge colonial rule. Physical fitness became an expression of cultural power and resistance.

A loosely connected movement emerged to synthesise a modern indigenous physical culture using traditional styles and the global methods of the international movement.

Professor Rajratna Manikrao set up the Vayam Mandirs or Temples of Exercise, which taught athletics, paramilitary drills and traditional martial arts. Manikrao's militant movement aimed to produce a potential army of strong, well-trained men who would ultimately challenge British rule (Singleton).

Along with Iyer and others, Manikrao was responsible for the proliferation of traditional akharas (gymnasia or wrestling schools), places that taught a mix of traditional and modern bodybuilding and exercise. These akharas often served as centres for political struggle, where the practice of yoga became a cover for martial arts training and resistance – a conscious evocation of the militant yogi ascetic of the past.

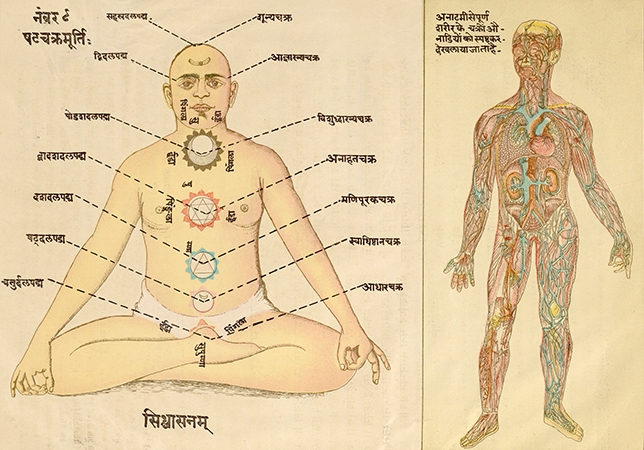

An early example of the trend to map the metaphysical yoga body onto the scientific anatomical body in a work by Swami Hamsasvarupa, c. 1900–10.

Yoga as therapy

Jaganath Gune was a young man who trained in one of Manikrao’s Vayam Mandirs in 1907. But his main influence was the yoga ascetic Sri Madhavadas (1798–1921), a Bengali barrister-turned-renunciate who established an ashram in Gujarat.

Yoga scholars (Atler and Singleton) have noted the significance of Madhavadas as the teacher of two yoga modernisers, Kuvalayananda and his contemporary Yogendra, who between them laid the foundations of the health and fitness dimension of modern yoga and yoga therapy.

Swami Kuvalayananda.

Gune joined the ashram for two years, adopting the name Kuvalayananda, and there he practised and learned a form of hatha yoga that prescribed asanas, kriya and pranayama for medical problems.

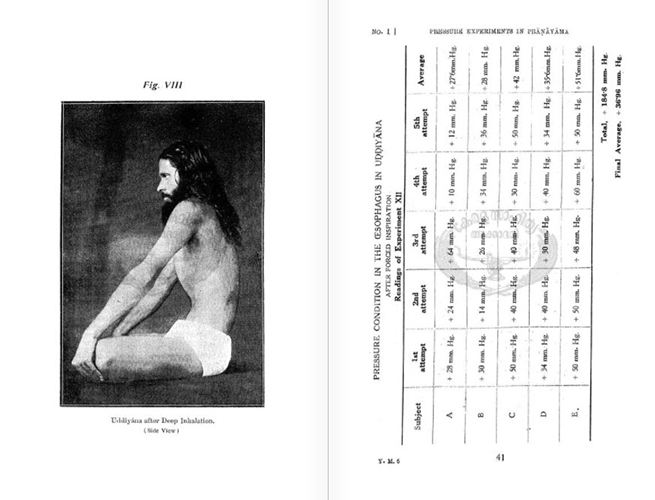

In 1921, Kuvalayananda took what he learned from Madhavadas and combined it with his own interest in scientific research to create a yoga research centre at Lonavla on the outskirts of Bombay (now Mumbai).

He and his researchers measured the physiological effects of asanas, pranayama, kriya and bandha in order to develop a therapeutic yoga practice. Their findings were published in the Institute's journal called ‘Yoga-Mimansa’, a mixture of scientific review and illustrated yoga manual. By drawing on the authority of science, Kuvalayananda gave yoga a greater status in the modern world.

Pages from the scientific section of the journal 'Yoga Mimansa', showing blood-pressure measurements for the posture.

In a clear crossover between physical culture and yoga, Kuvalayananda developed a yogic system of physical education for schools in the states of Gujarat, Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh, drawing on Manikrao's mass drill programme.

The ‘nature cure’

As a boy, Madhavadasji’s other pupil, Yogendra (born Maribhai Desai) had suffered a serious bout of typhoid. Growing up in cosmopolitan, middle-class Bombay, he took up wrestling and physical training in his teens, gaining the nickname ‘Mr Muscle-man’.

In 1916, after hearing a talk by Madhavadas, and to his father's dismay, he gave up his college studies and went to stay in Madhavadas's ashram.

Two years later Yogendra returned to Bombay. With the help of his wealthy patrons, he established the Yoga Institute, a place that had health and healing at its heart. The Bombay middle classes were familiar with international physical culture systems such as Swedish gymnastics. They saw the physical yoga revival in the same way – as a ‘movement cure’ for health and fitness.

Building on his success in Bombay, Yogendra decided to follow in the footsteps of the Rajah yoga innovator Vivekananda and others, and take his technique to America. During his four years in America he promoted yoga as a form of therapy, giving lectures and demonstrations. By 1920, he had raised enough support to set up an American Yoga Institute, which operated as a sanatorium and appealed to the alternative medicine community. Harvey Kellogg – the doctor and inventor of the breakfast cereal – was among his supporters.

Rehabilitating hatha yoga

Yogendra was the ‘householder yogi’. He was married and had a family. His yoga was a sanitised, modern form of hatha yoga, designed to appeal to the respectable middle classes as a health and fitness activity.

Like Vivekananda, he was keen to distance it from the disreputable persona of the ‘wild’ yogi. But unlike Vivekanada, who rejected physical yoga altogether, Yogendra rehabilitated it into a rational, domesticated practice, which could ultimately lead to “physical well-being, mental harmony and moral elevation”.

He saw yoga as a holistic practice with an ancient tradition, and he was dismissive of what he saw as adjuncts such as surya namaskars. “Surya namaskars or prostrates to the sun – a form of gymnastics attached to the sun worship in India” were “indiscriminately mixed up with yoga physical training by the ill-informed”, he insisted.

Yoga not yoga?

Kuvalayananda was also familiar with surya namaskars. Mark Singleton points out that the Bombay Physical Education Committee syllabus Kuvalayananda developed for schools in the province has a chapter devoted to “individualistic exercises, dands, baithaks, namaskars and asanas”.

In this chapter, namaskars are distinct from asanas, but both are categorised as physical training. The surya namaskar sequence he presents is a series of dands, described as Ashtang dand, probably in reference to an existing position known as Ashtanga namaskara, in which eight parts of the body touch the ground simultaneously. At this point, surya namaskar is not recognised as a sequence of yoga asanas but, like yoga, it has been put in the category of physical culture.

By the late 1930s, all the elements of modern yoga are present in colonial India: the synthesis of modern and traditional physical techniques, the therapeutic methods for health and well-being, and the ancient spiritual and mystical roots that appealed to orientalists and New Agers in the West, and nationalists in the East.

All these elements existed in what has been described as the crucible of global yoga, the Mysore school of yoga. And it was there that the surya namaskars so beautifully demonstrated by Eunice entered the canon of yoga asanas.

About the author

Lalita Kaplish

Lalita is a digital content editor at Wellcome Collection with particular interests in the history of science and medicine and discovering hidden stories in our collections.