Buildings affect how we sleep, work, socialise and even breathe. They can isolate and endanger us, but they can also heal us. In this extract from ‘Living with Buildings and Walking with Ghosts’ , Iain Sinclair explores the relationships between social planning and health, taking detours along the way.

“Above resistant pavements, I floated”

Words by Iain Sinclairaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Book extract

Moving now, we are affected by the presence of individual buildings as by the trees of the forest. Each fossilised trunk its own history, each trunk part of a more complex organism: the city. Our traces are felt in the communication between buildings as they register our passage. The system is in precarious balance. Our moods adjust to reflections and shadows and the crowds that surge and flower, parading their neuroses.

When my wife, recuperating, no longer accompanied me on a morning walk through a certain quiet street near Victoria Park, total strangers emerged from behind their windows and drawn curtains to ask what had happened. Was she well? Sleeping houses feed on the sugars of passerines, unconscious messengers.

In smeared twilight, a dip of the shoulder south of Euston Road, clamping my lips to avoid the sour drench of stalled, snarling, emphysemic vehicles and the eternity of improvements bringing restless London to a shuddering halt in the underpass with its slow roll of overhead ad-porn, before the reef of hotels and terminal stations – and remembering John Evelyn’s ‘Fumifugium’, his 1661 denunciation of noxious stinks trapped in the funnel of the Thames Valley – I rediscovered the magic of movement.

Above resistant pavements, I floated. That miraculously accessed network of walkable streets, close passages, curves, crescents, and permitted alleyways that are still there, outside time, offering, for whoever wants to experience it, narratives of a submerged and continuing city.

By now I should be dead. Or, by any reasonable accounting, coughing up my lungs in an isolation ward on the Dartford Marshes, a day’s sail in a fever boat from the Isle of Dogs. But well-intentioned hospital colonies like Joyce Green on the Dartford Marshes, between sewage works and cemetery, supplied by regular infusions of workers who couldn’t work (and their children), were no longer there. Blots on the OS map, ghosts of progress. The generous airing courts and suntraps were now shelters for rodents.

I could only surmise, after so many years tramping the major traffic ditches and motorway fringes, that somehow, by regular homeopathic doses, my country-born immune system had learned to thrive on pollution. The pores might be clogged and scurf grey, the pouches of the lungs black and tarry, but they seemed to function. Just so long as they remained untested and unrecorded in the medical system. And so long as I kept well away from germ-free, open-plan offices, those temperature-controlled corporate conservatories wallowing in the wrong sort of light. Those suffering interior jungles with their immodest art-substitutes: both unfinished and overfinished. The hard Scandinavian chairs in nursery colours: canned salmon, loud yellow, grape and lime.

Hospitals, universities, collections: they are all about waiting. Securing a round table. Accessing the right screen. Postponed meetings to confirm the next meeting. These buildings are quotations that should never have been released from the catalogue. They are enclosed streets, the CGI version of Walter Benjamin’s Parisian arcades: airless atria in which to put on time.

There is a bell jar microclimate of lassitude and anxiety. World news is framed on a high screen (mute) like a devotional painting from the future. Being here, an accredited temporary migrant, you are insulated against harm. The suspended monitor is a superstitious offering to keep us safe from what is happening outside. The fires, the rubble. Post-traumatic child eyes. Undressed wounds. Feasting flies. The bombed hospitals accused of sheltering bombers.

Coming off the street, you will always encounter a melancholy security guard, shamed by ill-fitting uniform, paid to stand and yawn, before allowing the right sort of petitioner access to a reception island efficiently womanned by dispensers of laminated badges – who reluctantly concede an advance on blast-repelling barriers, card-activated non-revolving doors (supervised by more uniformed security). And all of it a humourless joke witnessed by surveillance cameras charged with providing content for unwatched screens. Unwatched unless the terrible thing happens. Again.

There was a meeting to attend in one of the smartest hangars on Euston Road. There are always meetings in flexible spaces serviced by refreshment stations where discounted coffee is released on contact with a contactless card. Today I was beginning to consider the Pepys Estate in Deptford. It was strange to be researching a downriver episode of social housing from the 1960s in a location that seemed to deny that such things had ever happened, except as case files.

I thought of the helicopter jeremiads of John Betjeman from a poetically voiced documentary of that era. Oh dear! Oh dear! Those broken lifts! The pinched lives on the 20th floor of a riverside block, a slab, unredeemed by prospects of nautical Greenwich and the distant hills. “Caged halfway up the sky,” the poet moaned. He was talking about the latest high-rise towers, not the helicopter. Which, very wisely, he refused to enter. Deptford horrors were endured in an editing suite.

Schoolboy in his living room posing for the photographer, Pepys Estate, Deptford. Tony Ray-Jones, 1966.

And then there were the social-realist captures of Tony Ray-Jones, who seemed to be anticipating Ken Loach and Mike Leigh – the life of others – when he was commissioned to make a photographic record of the Pepys Estate: old men wearing their caps and trilbies on gravity-depressed sofas in low-ceilinged cabins, and estate kiddies at unsupervised riot on windswept concrete decks. The word ‘estate’, tried out in Deptford, came with its own heritage, summoning unreliable memories of cultivated gardens and private parks with grand-tour Roman statuary.

John Evelyn, the diarist and neighbourhood magnate of the Restoration period, enjoyed good health and kept clear of the surgeons who gave his friend Samuel Pepys such a rough ride in extracting a kidney stone the size of a tennis ball. Pepys was a hypochondriac with much to be hypochondriac about.

When the mortal shadows came for Evelyn in 1682, the diarist made an inventory of Sayes Court and put his papers in order, while he waited stoically for the worst. He countered a series of unexplained fits, arriving upstream like dreadful intelligence from the City, by sitting inside a “deep Churn or Vessell” and swallowing an infusion of thistle. The Restoration period, with its coffee-house conversations and newly founded Royal Society, was fertile ground for enlightened quackery and amateur experiments in disciplines still to be defined and regulated.

Seasonal plagues were purged in fire. And rational geometries proposed for a new city. Immigrants, economic or in flight from religious persecution, brought new ideas, new technologies. Both Evelyn and Pepys were elected as fellows of the Royal Society. They attended meetings and lectures. And demonstrations ranging from the art of veneering to the virtuoso dissection of opium-fed dogs.

Sir Kenelm Digby, a naval commander and diplomat, floated the notion that wounds could be closed by first healing the weapon, stroking a “sympathetic powder” along the edge of the blade that made the cut. Evelyn’s language – he wrote much and aborted more – was as prolix and neurotically discursive as my own struggle to lay out a coherent general theory about buildings and health.

‘Living with Buildings and Walking with Ghosts’ is out now.

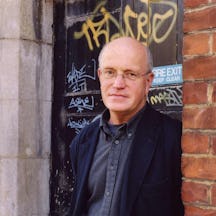

About the author

Iain Sinclair

Iain Sinclair was born in south Wales. He went to school in the west of England and university in Dublin. He lives, walks and writes in east London. His books include 'Downriver' (winner of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and the Encore Prize), 'Lights Out for the Territory', 'London Orbital', 'Hackney', 'That Rose-Red Empire', 'American Smoke' and 'The Last London'.