Light has a big impact on our bodies’ sense of time, and light pollution is increasingly affecting our health. But researchers are discovering how urban light design can limit these effects.

Michael W Young feels the effects on his body whenever he spends time in Manhattan. Though his research team is based in New York, at Rockefeller University, Young lives outside the city and is accustomed to gentler surroundings. On his trips into town, he’s keenly aware of the unceasing lights and traffic noise.

This isn’t just personal. Together with Michael Rosbach and Jeffrey C Hall, Young won the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for pioneering research into circadian rhythms, including the identification of the clock genes that regulate so much of our daily behaviour.

Light is one of the key zeitgebers, or timekeepers, that keep our internal clocks attuned to the outside environment. And light pollution is a major reason why, according to Young, “big cities are an impediment to the inner clock”. Too much or too little light can send our natural cycles off-kilter.

Does this matter? Being off-cycle has been linked to health problems, including the insomnia that’s symptomatic of circadian-rhythm sleep disorders (affecting people whose body clocks are set to unusual hours) and shift-work sleep disorder (affecting people who work during non-standard hours). Circadian misalignment has been linked with obesity, cardiovascular disease and psychiatric disorders. This shows how critical circadian rhythms are to maintain healthy metabolism, sleeping patterns and moods.

As Young says, “Our bodies work best when there is agreement between all these signals.” And the signals are disrupted by cities.

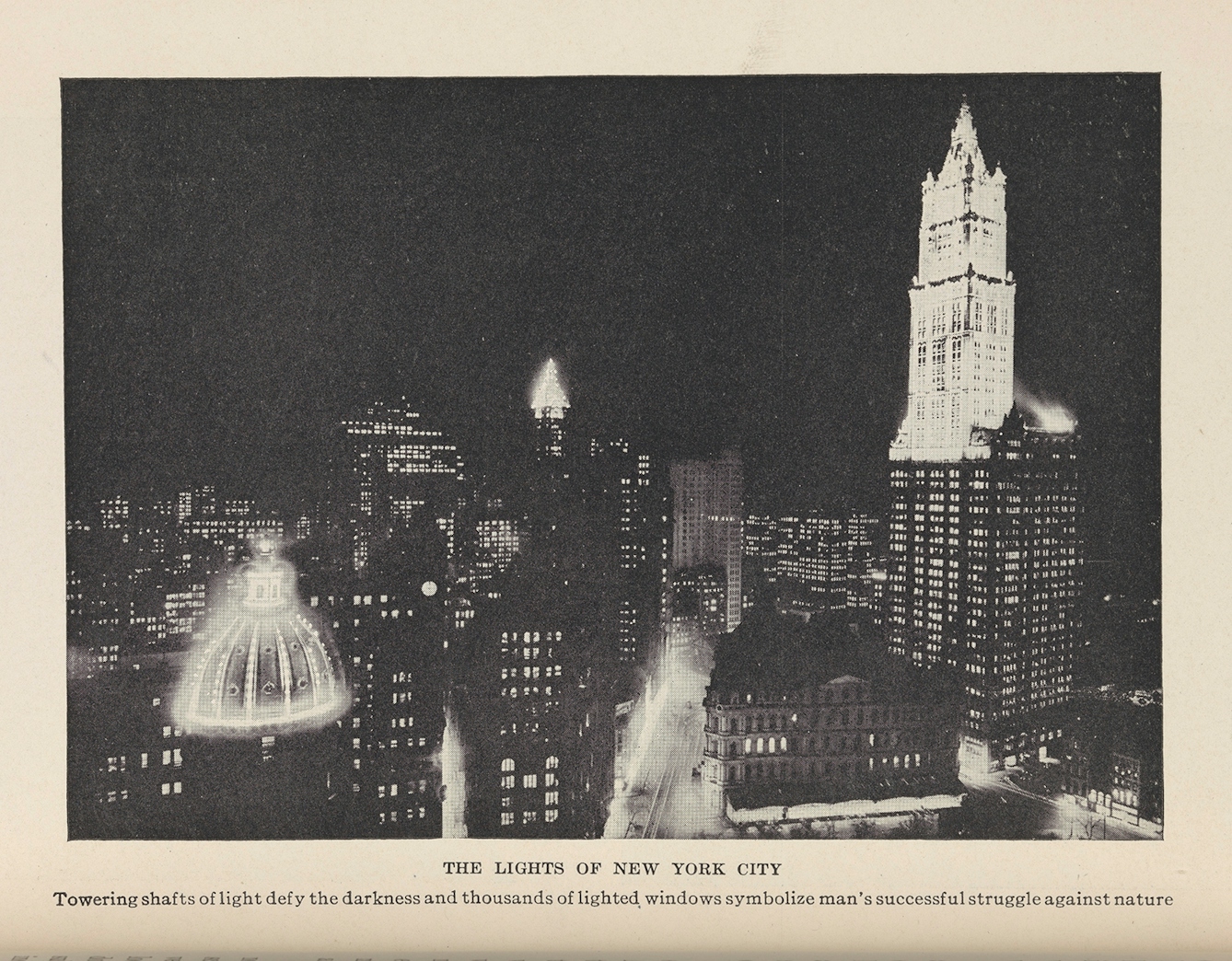

A satellite view of Manhattan at night.

The light-dark cycle of cities

Anna Wirz-Justice is a professor emeritus at the University of Basel’s Centre for Chronobiology in Switzerland, and part of the steering committee of the Daylight Academy, a network of scientists, architects and planners exploring the complementary roles of daylight and artificial light.

“Chronobiology,” as Wirz-Justice and urbanist Colin Fournier have written, “is the science of biological rhythms, more specifically the impact of the 24-hour light-dark cycle and seasonal changes in day length on biochemistry, physiology and behaviour in living organisms.”

Although she’s recovering from knee surgery when I get in touch with her, Wirz-Justice is happy to elaborate on chronobiology. About a decade ago, she explains, she and her colleagues realised that basic biological research was transforming “thinking about the effects of architecture and lighting design on human health”.

MORE: The growing awareness of eco-anxiety, or “a chronic fear of environmental doom”

Researchers had discovered novel photoreceptors located in the retina – cells that respond to light and spark biological processes. These photoreceptors were communicating with the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the hypothalamus, or the body’s ‘master clock’. In other words, it was becoming clear that light is key to how bodies keep track of rhythms – and architects and designers were taking note.

Lights with different wavelengths are one example. Blue light has been shown to be key for aligning circadian cycles during the daytime (although it can also lead to photoreceptor damage and possibly other health issues). Some lamp designs now incorporate stimulating blue light during the day, fading into warmer shades at night.

Flexibility can also be incorporated into building design. For instance, transparent surfaces could let in the winter sun but limit the summer sun, or adjustable window slats could be repositioned during the day. Buildings equipped with sensors could adjust certain features based on light levels and occupancy conditions.

‘Artificial light: its influence upon civilization’, published in the 1920s, celebrates the lights of New York City: “Towering shafts of light defy the darkness and thousands of lighted windows symbolize man’s successful struggle against nature.”

Behavioural changes in cities

While advances in lighting technology have been remarkable, technological innovation isn’t the only way forward. Not least because it may not be cities themselves that are incompatible with humans’ inner clocks but the lifestyles associated with them. Some researchers have found that ‘social jetlag’, or the mismatch between social and biological clocks, is greater in urban areas.

Anna Wirz-Justice feels, “a lot can be done by more conscious light-oriented behaviour”, which would create greater harmony between the body’s clock and society’s pace of life. For example, an urbanite frequently feeling fatigued and out of sync could invest in blackout curtains or light banks to help stay on-cycle.

While Michael Young agrees that “to some extent an individual may be able to control the environment”, Bob Mizon argues that, in the UK, “the only real solution to sorting out over-bright lighting… is through planning”.

Mizon is the coordinator of the British Astronomical Association’s Commission for Dark Skies, which campaigns against “lighting that goes where it’s not needed, when it’s not needed”. The Commission for Dark Skies is part of a larger dark-sky movement that seeks to reduce light pollution and carve out dark sites where people can enjoy the ecological, psychological and astronomical benefits of properly seeing the night sky.

“I don’t think there are many things better than being able to see the Milky Way… Something about looking up at the stars on a dark night makes you feel both small and big in a very meaningful way,” says photographer Cristofer Jeschke.

Better planning for better biological calibration

Speaking from his home in Dorset, Mizon is clearly an outspoken, passionate campaigner against excess light. He’s seen progress with more downward-pointing lights, but one bugbear of his remains sports grounds with intense floodlights that shine upwards. “For heaven’s sake, point it at the cricket. Don’t point it all over the place,” he pleads.

In Mizon’s view, homeowners and facility managers should seek planning permission from local authorities before installing disruptive lights, the same way they’d seek out the advice of professional electricians or ecologists ahead of major building works.

Choosing recommended lighting with reduced intensities or more circadian-friendly wavelengths wouldn’t be challenging. The problem is more attitudinal, because of what people are accustomed to. “The public just don’t realise what they could have,” says Mizon. “They think it’s normal to have glare-y, over-the-top lighting, and are quite surprised when you tell them it can be better done.”

However, not all chronobiology-friendly changes are welcomed. Bright streetlights in urban spaces are associated with public safety, particularly for women. Dimming them at night might be controversial (although consulting with communities about preferences for wavelengths and light levels has shown some promise).

And the convenience of living in a large, 24/7 city – being able to nip out at all hours for a pizza, for instance – would be missed, even if it’s at the expense of healthy circadian rhythms.

Let there be (the right kind of) light

Excess light pollution is a problem, but access to natural light is a necessity. As Anna Wirz-Justice points out, “a minimum amount of daylight is important to health”. She says that, even in rainy Glasgow, just being outside for 30 minutes a day will expose a resident to light much brighter than anything that can be found indoors.

It’s a right to the right kind of light that the ancient Romans and Greeks recognised: property-based rights to sunlight were protected through court decrees in ancient Rome; ancient Greeks did the same via planning schemes.

To keep in sync with our natural rhythms, it seems what city dwellers need is plenty of natural light and a lot less of the artificial kind. But, whether the focus is on better design, tighter regulation or behavioural change, it should be possible to live in a densely populated area without our internal clocks going completely cuckoo.

About the author

Christine Ro

Christine Ro is a journalist whose work is collected at www.christinero.com.