Should we look beyond individual therapy to community activism to help people experiencing eco-anxiety?

“I’ve been concerned about the possibility of environmental collapse since I was a young child,” Alice McAlpine tells me. An avid hiker, she’s seen the direct impact of environmental damage when out on the trails near her Northern California home. The landscape is drier, and she notices the absence of certain bird species.

Alice has a history of anxiety and depression. This includes, as she says, “the observation of things that aren’t working” – from homelessness in San Francisco to oil drilling around the Texas cattle farm where she spent much of her childhood. “I am so wired to notice when the landscape is changing, when the landscape is deteriorating.”

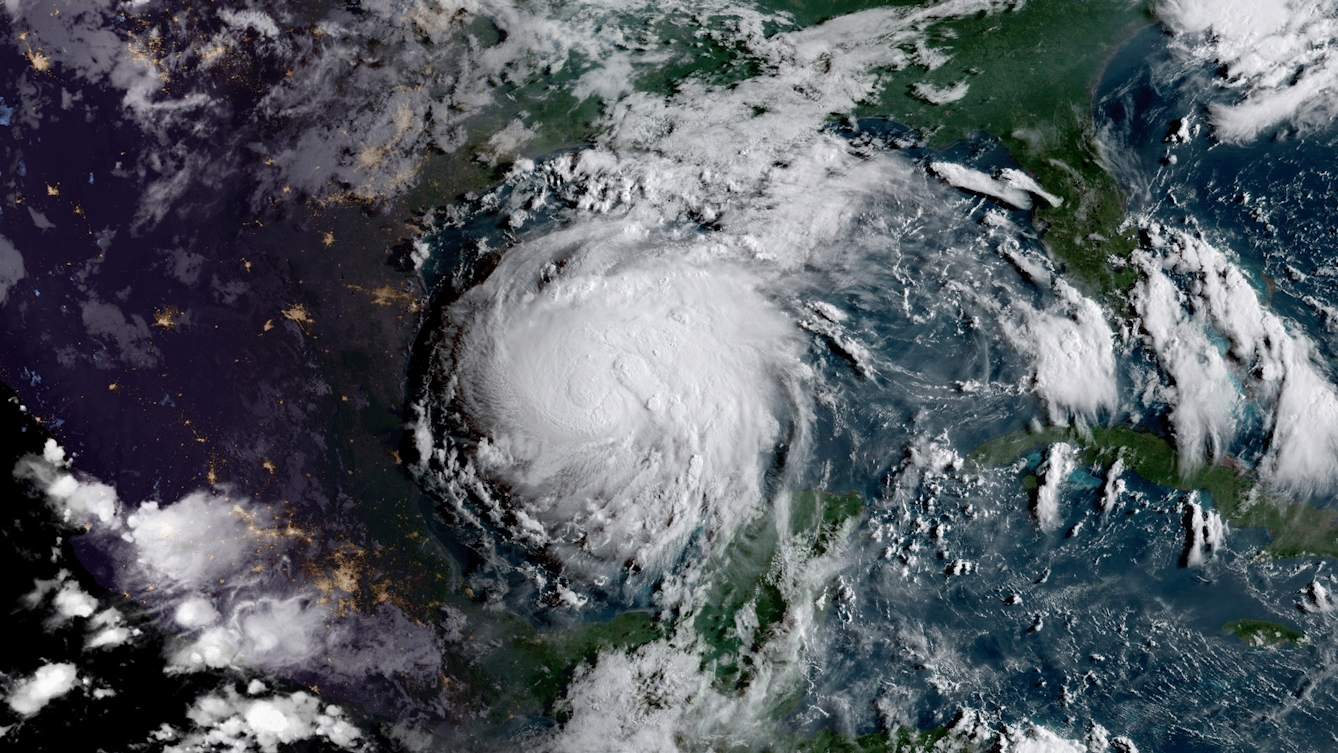

Satellite imagery shows Tropical Storm Harvey intensifying into a hurricane. Uncertainty, worry and stress linked to the possibility of a natural disaster can be psychologically distressing.

This isn’t abstract for Alice. While she lived with hurricanes growing up, she feels that the climate change-related severity of storms such as 2017’s Hurricane Harvey is something new. She worries for her son and daughter-in-law, living in Houston.

She is far from alone.

The rise of eco-anxiety

Environmental concern is reasonable and desirable, but not if it’s paralysing. Recent years have seen growing awareness of the condition known as eco-anxiety, which the American Psychological Association has defined as “a chronic fear of environmental doom”.

The concept has attracted some detractors, who criticise the pathologising of this kind of anxiety or its typical use in rich-country contexts. Yet, there’s a growing momentum in the psychology community behind recognising and finding solutions to eco-anxiety, both to assuage individual stress and to work toward environmental protection.

It’s well established that climate change affects psychological wellbeing in a number of ways. After all, those directly affected by a climate change-influenced disaster risk losing homes, livelihoods, and loved ones. Also psychologically distressing are constant uncertainty, worry and stress linked to the possibility of a natural disaster. Of course, pre-existing vulnerability – whether of disability, age, poverty, or other factors – worsens the likely severity of these things.

High temperatures have also been linked to suicides of farmers in India and Australia, and air pollution has been connected with increased suicide rates in north-east Asia.

Concern about environmental damage can affect wellbeing less directly, too. Secondary or vicarious trauma refers to the knock-on distress caused by feeling helpless when seeing others in distress. At the same time, hope about the future is associated with better psychological and physical health.

Alice McAlpine at the organic farm where she works. She’s found this kind of hands-on activity helps her cope with eco-anxiety.

How therapy and activism can help

Elise Amel, a psychology professor at the University of St Thomas, researches ecopsychology. She tells me: “While it is important to validate our emotions associated with climate change (such as a fear of the unknown, loss of special places or activities, worry about future), it can be debilitating to stay focused on the negative emotions. Instead, people who take action have a greater sense of control, and taking action with others can lighten the emotional burden.”

This is a state that Alice McAlpine is seeking to reach. And it’s one reason why she sees therapist Leslie Davenport once a month.

Author of ‘Emotional Resiliency in the Era of Climate Change’, Davenport is a clinical psychotherapist with 25 years of experience. These issues are close to her heart; she has volunteered for campaign group 350.org and Red Cross, as well as participating in demonstrations related to environmental policy.

Davenport has other clients, besides Alice, who are deeply concerned about the impact of climate change, to the point of it affecting their psychological wellbeing. With these clients, Davenport tends to use a combination of internal and external therapeutic strategies.

One technique puts clients into a less anxious mindset by encouraging them to imagine peaceful settings. Davenport explains: “What you do with that increased awareness and understanding, whether it’s changes in your lifestyle and/or activism, is creating a congruence between what you understand and how you live your life.”

Comfort in community

This includes finding a sense of community. Alice has started work on an organic farm, which she describes as “a way to be in a community with like-minded people, who care a lot about food, how food is grown, and take care of the earth in the most meaningful way”.

This kind of practical activity suits her better than a capital ‘A’ kind of activism. As she says, “There’s a part of me, and I think this is just the way I’m wired, that if I talk a lot with people about these topics, it can increase the amount of helplessness.”

Leslie Davenport also recommends small-scale local action: “One of the ways to overcome helplessness, whether that moves into anxiety, or more towards depression, is to be engaged. That really doesn’t have to be ‘Get out on the street and carry a sign’ or ‘Sign a petition’. What it means to be active or an activist… manifests in any number of ways.”

A climate change march in Washington, DC in 2017. One way to overcome helplessness is to be active, but that activism can manifest in different ways.

Finding a local sphere of influence

The implications of climate change are so massive that they might be psychologically destabilising, and thus some people have responded by denying that climate change exists. But Davenport says: “If we build a capacity to stand in the face of difficult things – information, events, possibilities – we don’t have to turn away as much… If we’re able and willing to touch the parts of life within the sphere of our own influence, whatever that might be, then we can really roll out this wave of more positive change.”

This is a lesson echoed in recent research on climate psychology, including an influential 2017 ‘Science’ paper coauthored by Elise Amel, which points out that it’s important to move from an individual therapeutic focus to an emphasis on collective action for environmental preservation.

This isn’t an either/or situation. There doesn’t need to be a stark divide between what’s good for the individual and what’s good for the collective. Individual coping can contribute to larger-scale action, and community action can be especially powerful in climate-affected places where economic resources are limited, such as in Thai villages with many elderly residents.

Of course, no amount of activism or advocacy is going to make up for the loss of a home, a loved one, or a way of living, which climate change is precipitating around the world. But, as Alice acknowledges, “it’s probably in taking the actions that… have the more therapeutic effect, where you just don’t sit around worrying about it, you actually feel like you’re doing something”.

About the contributors

Christine Ro

Christine Ro is a journalist whose work is collected at www.christinero.com.