On the combustion of gas for economic purposes / by Henry Letheby.

- Henry Letheby

- Date:

- [1866]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: On the combustion of gas for economic purposes / by Henry Letheby. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The Royal College of Surgeons of England. The original may be consulted at The Royal College of Surgeons of England.

11/16 page 11

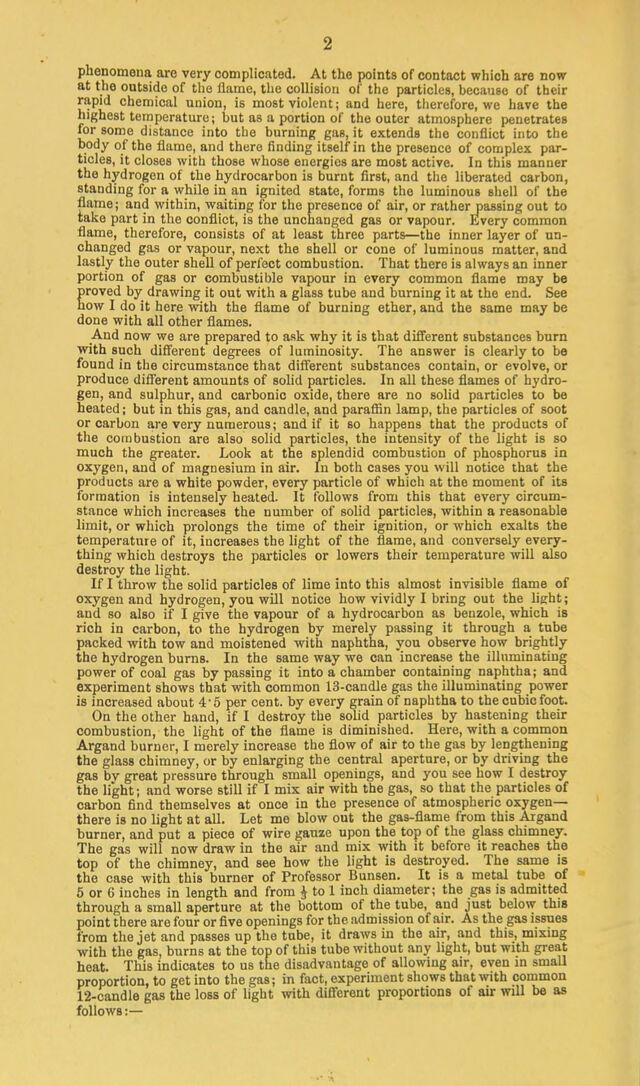

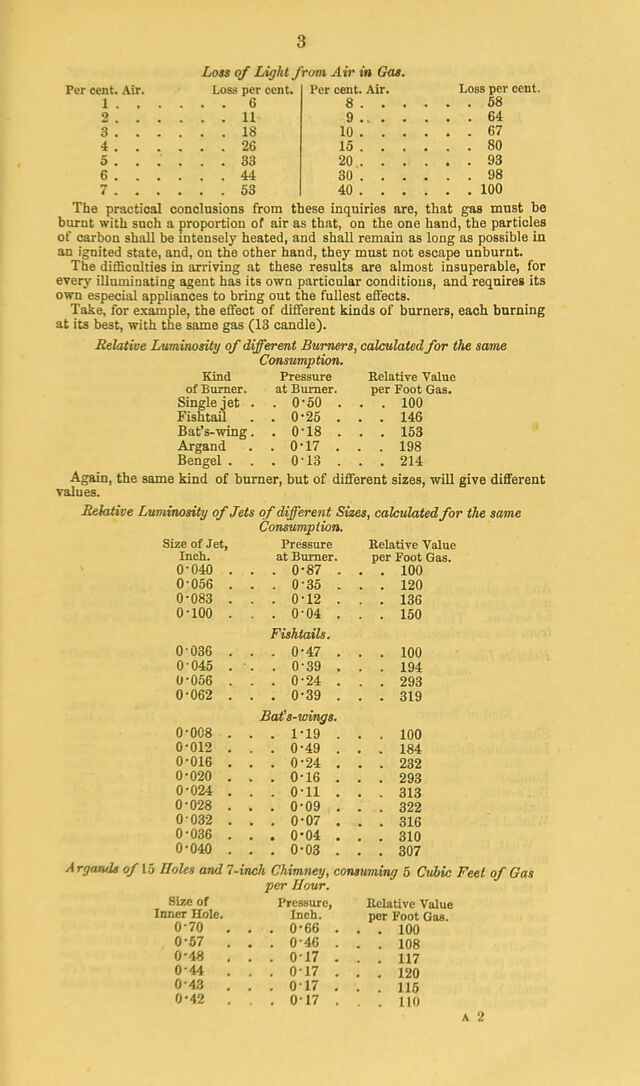

![1 ] And now I will briefly describe the contrivances which are used for in- creasing, or rather I should say for fully developing, the temperature of burniug gas. 1 have shown you that tho light of a flame depends on the presence of ignited carbon; if, therefore, by any contrivance we can at once burn this carbon, and not permit it to stand as it were idle in an ignited condition, the temperature must be considerably increased. This is the principle concerned in all the contrivances for developing the heat of gas. One of the simplest means of accomplishing this is to mix a sufficient quantity of air with the gas before it reaches the place of combustion; and this is easily done by putting a cap of wire gauze upon the chimney of an Argand burner, and setting fire to the gas above it. The effect of this arrangement is that as the gas passes from the burner to the top of the chimney, it draws in a quantity of atmospheric air, which freely mixes with it and burns the solid particles. The same is the case with the burner of Bunsen, which I have already described; and you will note how strongly it ignites this platinum crucible. The same arrangement is adopted by Mr. Griffin in his reverberatory furnace, which is a Bunsen's burner en- closed in a clay chamber. I have here another contrivance of the same nature called an atmopyre, which is used by Professor Hofmann in his fur- nace for effecting organic analysis. It is a hollow cylinder of baked pipe- clay pierced with a large number of small holes. When it is placed on a small fishtail burner, the gas, in issuing from the holes, draws in a sufficient quantity of atmospheric air to make it burn at all the apertures with a clear blue fight; and thus the temperature is so much increased that the entire body of the numerous cylinders composing the furnace becomes almost white hot. But we shall find that a still higher temperature is obtained by blowing air into a large volume of flame. This is the plan adopted by Mr. Herapath in this blow-pipe jet. Observe how intensely it ignites a mass of platinum wire; and by putting together a number of these jets, as Mr. Griffin has done, in this arrangement, which he calls a blast-furnace, you will perceive what a high temperature is obtained; and by surrounding the blast with a case of baked clay, so that the heat may be concentrated, the temperature is sufficiently high to melt all the common metals. As much as a quarter of a hundredweight of cast-iron can be melted at a time in one of these furnaces; and 3 or 4 lbs. of cast-iron or copper can be thus melted in fifteen minutes. Even the very refractory metals, as nickel and cobalt, can be thus fused. And if instead of atmospheric air a jet of oxygen is used, as I will now show you, the temperature is still higher. This is the principle of Deville's furnace, which is a jet of oxygen blowing into a large flame of coal gas, and directed down upon the refractory substance; the whole apparatus being enclosed in a chamber of non-conductors. With this furnace large masses of platinum are easily melted, the platinum being placed upon a hollow bed of lime. I have seen a mass of platinum, weighing about 350 lbs., which had been melted in this manner; and I was informed by Messrs. Johnson and Matthey, the platinum assayers of Hatton Garden, that the mass required six hours for its fusion. During that time about 360 cubic feet of coal gas and the like quantity of oxygen were used; in fact, Deville found in his experiments at the Ecole Normale, that it required a little more than a cubic foot of gas and a cubic foot of oxygen to melt a pound of platinum. The temperature of the flame must be enormous; Calculated from the thermotic powers of gas with air and oxygen, it may be said that it is equal to about 522*° of Fahr. when air is used, and 14,320° with oxygen. The temperature of different combustibles is shown on the diagram on the following page, and you will notice that the highest temperature produced by the various constituents of coal gas is that of acetylene, or the vapour of benzole when burned in oxygen, the heat of which exceeds 17,000° Fahr.; the lowest temperature of all the constituents is about 12,700° Fahr., tho temperature of burning carbonic oxide. Oil the same diagram 1 have tabulated tho thermotic power of a great number of substances. It is expressed in the number of pouuds of water raise l°Fahr. by a pound of the substance, and when the body is capable of being converted into gas or vapour, I have also expressed it iu tho](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b22298356_0013.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)