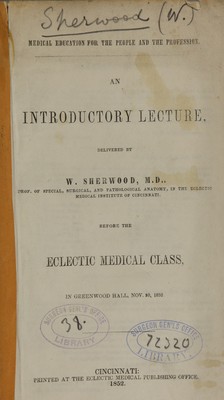

Medical education for the people and the profession : an introductory lecture / delivered by W. Sherwood before the Eclectic Medical class, in Greenwood Hall, Nov. 10, 1852.

- Sherwood, Wm. (William)

- Date:

- 1852

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Medical education for the people and the profession : an introductory lecture / delivered by W. Sherwood before the Eclectic Medical class, in Greenwood Hall, Nov. 10, 1852. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the National Library of Medicine (U.S.), through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the National Library of Medicine (U.S.)