Volume 2

The royal navy : a history from the earliest times to the present / by Wm. Laird Clowes. Assisted by Sir Clements Markham, Captain A.T. Mahan, U.S.N., H.W. Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt, etc.

- Clowes, W. Laird (William Laird), Sir, 1856-1905.

- Date:

- 1897-1903

Licence: Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

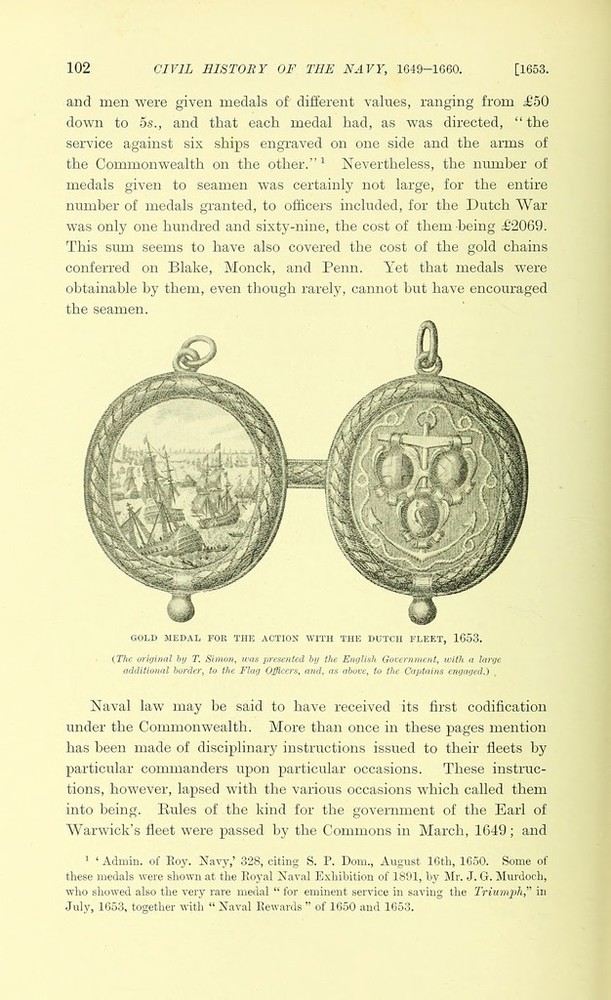

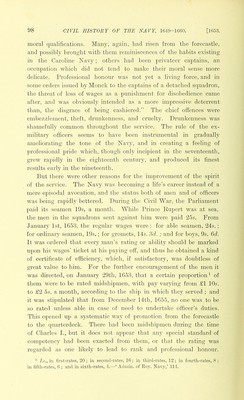

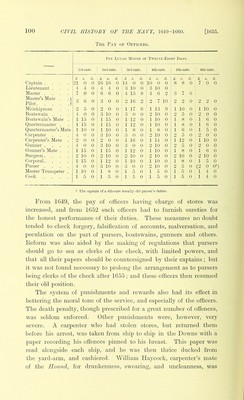

Credit: The royal navy : a history from the earliest times to the present / by Wm. Laird Clowes. Assisted by Sir Clements Markham, Captain A.T. Mahan, U.S.N., H.W. Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt, etc. Source: Wellcome Collection.