The mechanics' magazine, museum, register, journal, and gazette. No. 1128, Saturday, March 22, 1845 / edited by J.C. Robertson.

- Date:

- [1845]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The mechanics' magazine, museum, register, journal, and gazette. No. 1128, Saturday, March 22, 1845 / edited by J.C. Robertson. Source: Wellcome Collection.

4/20 (page 194)

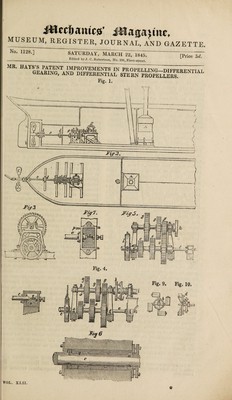

![MR. HAYS S PATENT IMPROVEMENTS IN PROPELLING—DIFFERENTIAL GEARING AND DIFFERENTIAL STERN PROPELLERS. [Patent dated July 3, 1844 ; Specification enrolled January 2, 1845. Patentee, Christopher Dunkin Hays, of Bermondsey, Wharfinger.] Mr. Hays’s improvements* consist, Jirst, in “ a novel mode of transferring the motive power of the engine to the propeller, whereby the latter may be driven at different speeds according to circumstances, and without the necessity for altering the speed of the engine.” Second, in an “ improved mode of con¬ structing certain of the working parts, whereby the friction thereof is consider¬ ably reducedand, third, in “a novel construction of propeller.” 1. According to the present mode of employing steam as an auxiliary power in propelling sailing vessels, the engines and propeller are only brought into use occasionally, and under certain circum¬ stances, such as during calms and light winds, but when favourable or strong winds prevail, the propeller and engine are thrown entirely out of use, and be¬ come so much dead and useless weight in the ship. Instead of following this plan, Mr. Hays proposes to make use of the auxiliary steam power continually, and under all circumstances, where it can be of the slightest use. With this view he employs such an engine and propeller as will be capable of pro¬ pelling a vessel unaided by any other pow7er, at a moderate rate of, say four or five knots per hour, during calms and very light winds, and by the adoption and employment of the differential gearing to be afterwards described, which he con¬ nects to the engine and propeller shaft, he hopes to be enabled at all times to -propel the vessel four or five knots per hour, or nearly so, beyond the speed that she would go if unaided by his apparatus. “ For example,” says Mr. Hays, “ sup¬ pose that the engine will propel the vessel at the rate of four or five knots per hour in a dead calm, if a light wind capable of pro¬ pelling her two knots per hour,without other assistance, should arise, then by the addi¬ tional power of an engine and propeller with my apparatus adapted thereto, I shall by the two powers combined, be enabled to propel the vessel, say about six or seven knots per hour, and if the wind should increase so as * For previous notice of these improvements see letter of Mr. Hays in our journal of the 11th of Ja¬ nuary last. ■ ’ (unaided) to propel the vessel four or five knots, then by the additional power of the engine she will proceed at the rate of eight or nine knots per hour, or nearly so, and so on according to the wind. * * * * * In order fully to understand this point, it will be necessary to examine what would be the effect of the ordinary auxiliary steam power upon the progress of a ship. Sup¬ pose this auxiliary power is calculated to propel the vessel four knots per hour un¬ aided by any other power, and to effect this object the propeller is obliged to make sixty revolutions per minute—now if a wind springs up which, unaided, is also capable of propel¬ ling the vessel at the same or a greater speed than the engine is calculated for, it follows that although the propeller may still revolve sixty times per minute, still there is no (or at any rate very little) increased speed im¬ parted to the ship, and the propeller is re¬ volving uselessly, as the passage of the ship through the water would of itself drive the propeller at nearly the same speed if the latter were detached from, the engine. The method I adopt in making the propeller available under these circumstances, is to drive it at a speed greater than that which the progress of the ship itself would give the propeller in its progress through the water— that is to say, if the speed of the ship sailing four knots per hour, is such as would cause the propeller to revolve sixty times per mi¬ nute, if detached from the engine, it is clear that it will be necessary for the engine to drive the propeller an additional sixty, mak¬ ing one hundred and twenty revolutions in all, in order to propel the vessel about eight knots per hour. It will be understood that the engine is not required to exert any increased power to obtain this increased speed, as the ship’s motion drives the pro¬ peller one sixty, and the engine the other sixty revolutions ; the wind, therefore, by means of the motion of the ship through the water, assists in driving the propeller, and the engine gives it an additional impetus. If the vessel is propelled by the wind at the rate of six knots, a further increase, equivalent to an additional four knots, must be made in the speed of the propeller before the full benefit is obtained from the power of the engine, and so on according to the increased power of the wind.” The accompanying engravings show the method which Mr. Hays adopts. Fig. 1 represents a longitudinal vertical sec-](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b30390783_0004.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)