Revealing the realities of the Middle Ages is at the heart of Jack Hartnell’s new book ‘Medieval Bodies’. He argues that, in order to truly grasp any aspect of the medieval world, we need to look beyond caricature to the nitty-gritty detail of life, death and art. In this extract, he explores what our two worlds have in common, and the vagaries of chance.

You, a thousand years ago

Words by Jack Hartnellaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Book extract

Exploring medieval bodies is particularly vital today, because their era continues to be much misunderstood. The centuries sandwiched between the accolades of ancient Greece or Rome and the classical world reborn in the European Renaissance are seen as a static and sequestering time, an idea we read in their different names: the ‘Dark’ Ages or the ‘medieval’, from the Latin medium aevum, a ‘Middle Age’.

It is a moment often defined by events outside itself, by what it is not, and when we look at medieval artefacts – be they bodies or poems, paintings or chronicles – we have a tendency to emphasise the negative. We draw them into a sceptical, and often quite gruesome, narrative of the period that has been handed down to us.

But, if you or I were to be transported back a thousand or so years from the present into the medieval past, we would find ourselves in an uncanny place at once startlingly different from and yet strangely familiar to our own.

Most striking, might be its apparent emptiness. Demographically speaking, medieval populations were significantly smaller: there are roughly as many people in the United Kingdom today as there probably were across the entirety of Europe in the Middle Ages. Many of them lived in small towns and villages, the cumulative engines of a largely agricultural economy, and in the absence of jet planes and motorways life might feel surprisingly quiet.

At the same time, we might visit larger civic centres such as medieval Cairo, Paris, Granada or Venice, whose crowded streets, busy markets and generally condensed living would feel just as bustling as many modern cities. The biggest of these would reach populations of half a million or more and harboured elaborate centres of political power, diverse industries and, later, a university trained intellectual elite.

Religion played a much greater role in medieval life than it does today. This oil painting from 1260-1318 shows the Madonna of the Franciscans.

Religion would be something we recognise too from modernity, yet it played a much greater role in the fundamentals of medieval life in a way that is now largely lost.

This is not to say, as the caricature sometimes suggests, that Christianity, Islam or Judaism was all anyone ever talked about. A good parallel would be the way we think and speak about science today. We do not go around slapping each other on the back and congratulating ourselves on the existence of gravity, constantly expressing gratitude and awe that Newtonian physics stops us from floating off the earth’s surface into space. Rather, it is a baseline for how we see and understand this world, its past, present and future.

Religious tenets like the biblical story of Creation or the potential daily intervention of the Almighty were an accepted, but not necessarily all-consuming, part of a medieval worldview.

Of course, while I am arguing that we have misjudged the Middle Ages, there is no getting away from the fact that it was, in many ways, extremely tough. By the standards of the present day, almost everyone in the pre-modern world right up to the 1800s would be classed as living in extreme poverty. Yet, medieval people were also aware that, when it came to the shape and fabric of individual living, we are all hostages to fate: our fortunes can rise as well as fall.

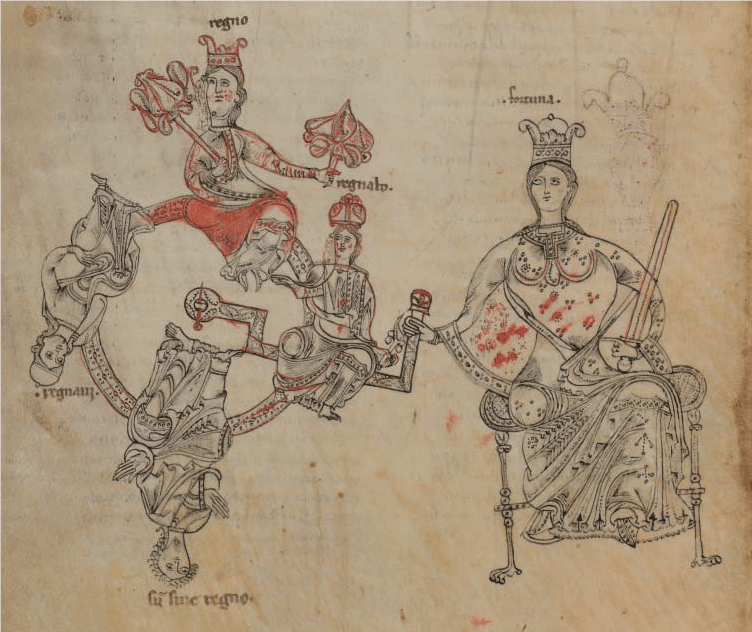

Here, the goddess Fortuna spins her wheel to change the fate of four kings. The image was added in the 11th century to a Visigothic manuscript written in Cardeña in 914 by a scribe named Gomez.

An illustration from a 10th-century Spanish manuscript shows the image of Fortuna, the Roman goddess of fortune who was also particularly popular with medieval moralists. Crowned and throned, the stunning Queen of Fate spins her wheel to twist a set of figures to and fro.

In this grand image, those shown at fortune’s behest are four kings. Some are in the ascendancy, while others are having their world flipped completely upside down. Tossed through time, the destiny of each is labelled in Latin beside them: regnabo (‘I shall reign’), regno (‘I reign’), regnavi (‘I have reigned’), sum sine regno (‘I am without reign’). But one more crank of the handle and everything will change again.

Far from being an exclusively royal hazard, the vagaries of chance were a reality of daily life for all. In the words of the English poet John Lydgate (c.1370–1450):

The enuyous ordre of fortunat meuyge

In worldly thynge false and flykerynge

Ne wyll nat suffre vs in this present lyfe

To lyven in reste without werre or stryfe

For she is blynde fykell and vnstable

And of hir course false and full mutable

The envious order of Fortune’s moving,

In worldly things false and vacillating.

None will not suffer it in this present life,

To live in rest without war and strife.

For she is blind, fickle, unstable,

And her course is false and mutable.

The medieval period, like today, had its winners and losers. This 11th-century mural from the church of San Crisogono shows St Benedict healing a man with leprosy.

Clearly, the Middle Ages saw itself as having both winners and losers. Most medieval cultures were indeed heavily stratified in this manner, with divisions between the haves and the have-nots reinforced by patterns of wealth and work. Those who owned land, at home or abroad, had both financial control of its produce – wool, wheat, wood, slaves, iron, furs, ships – and, by extension, political control of the people who wished to live or labour on it.

This is not to say that medieval living was entirely constituted of emperors and peasants, two camps polarised at totally different extremities of income: in between was a broad spectrum encompassing all sorts of groups, from busy professionals through to skilled craftsmen and an aspirational merchant class.

Yet a king could still expect his comfortable surroundings and ample diet to see him greatly exceed the average life expectancy of a labourer harvesting his royal lands, who might have struggled to make it to 40. The daughter of a wealthy lord might receive a thorough schooling at home, while her working-class counterpart would be unlikely ever to be able to read or write. The son of an aristocratic landowner could be welcomed through familial connections into the political ruling class or well-funded religious institutions, while the son of a farmer was expected to toil in the fields for his entire working life.

Like today, for those who found themselves at opposite ends of Fortuna’s Wheel, standards of living could be strikingly different.

‘Medieval Bodies’ is out now.

About the author

Jack Hartnell

Dr Jack Hartnell is Lecturer in Art History at the University of East Anglia. Jack’s research and teaching focuses on the history of art and visual culture in the very broadest sense, investigating the relationship between art objects and their makers, audiences, and original contexts. In particular he specialises in the art of the Middle Ages, where his work uses artworks as a gateway onto the complex cultures of medieval Europe and the Middle East. www.jackhartnell.com