Modern yoga owes a debt to the physical culture movement, which created a world obsessed with health and fitness.

Yoga gets physical

Words by Lalita Kaplishaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Serial

The world went sports crazy in the first quarter of the 20th century. The first modern Olympics had just been held in 1896, inspiring new interest in athletics and the Ancient Greek physical ideal.

The relatively new science of physiology – the study of the physical and biochemical systems of the body – provided criteria for how the body should perform. This new emphasis on the link between health and exercise inspired a growing culture of physical improvement.

Several individuals developed their own personally branded exercise systems. These ‘celebrity trainers’ often used themselves as proof of the success of their system, from the military and medical origins of P H Ling's Swedish gymnastics, to the self-improving daily routine of J P Müller, and the showmanship and mass appeal of Eugen Sandow's bodybuilding. Exercise was not only a trend for men: Genevieve Stebbins was one of a number of women who developed exercise systems suitable for the modern woman.

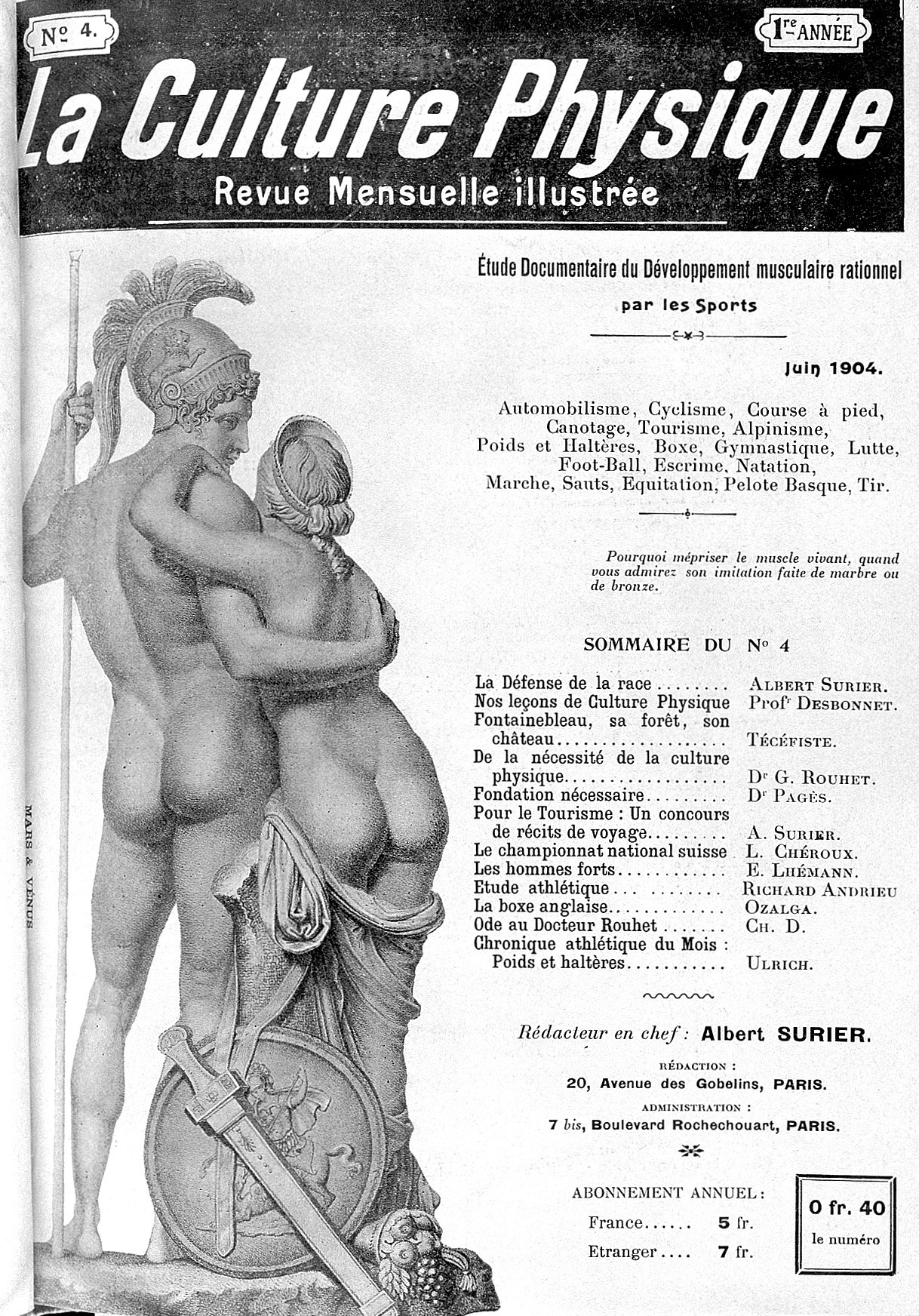

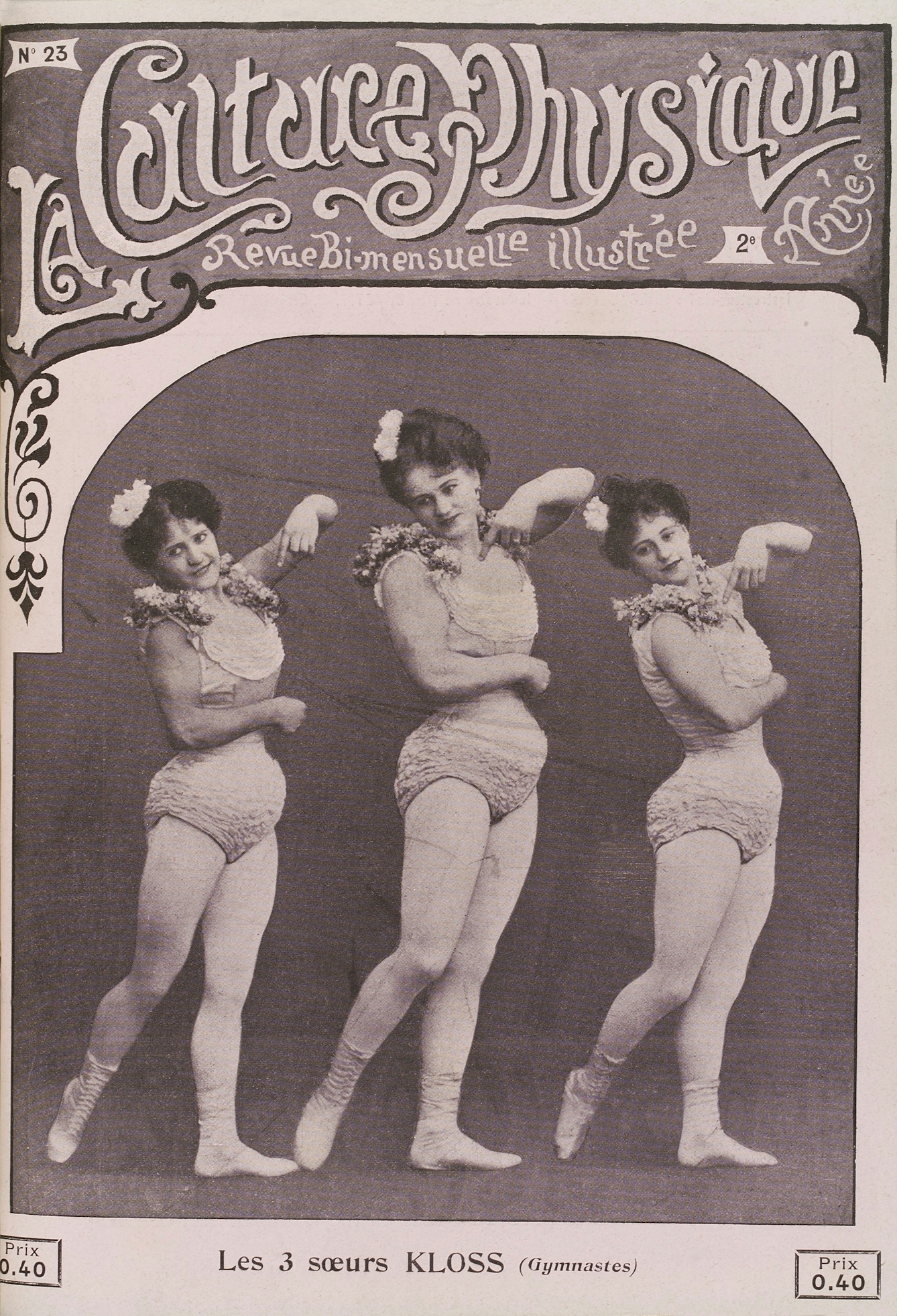

In pictures

Popular physical culture magazines frequently alluded to the ancient Greek ideal, with modern athletes posed in classic poses.

As bearers of the nation's future, women's health and fitness were important.

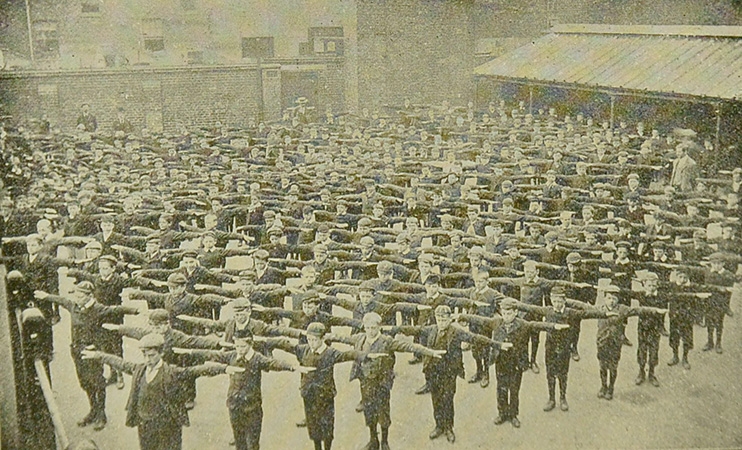

Schoolchildren practising exercise drills, 1900s.

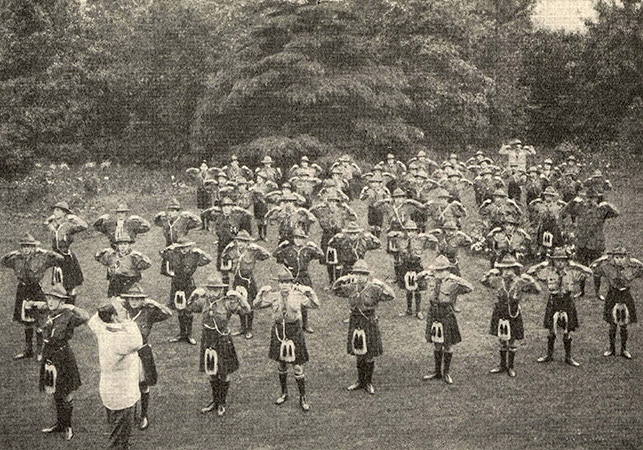

Boy Scouts practising exercise drills, 1917.

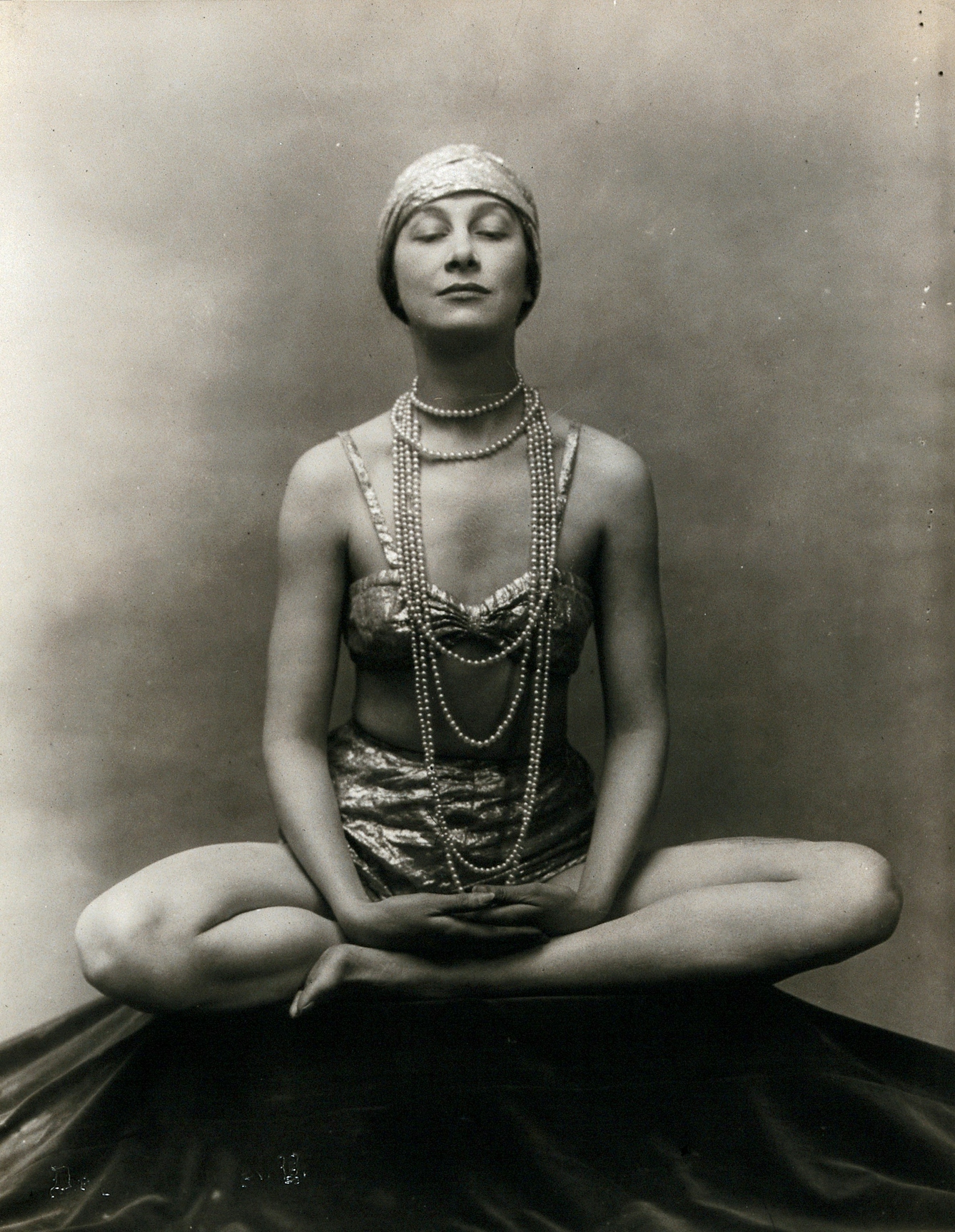

Marguerite Agniel, author of the book ‘The Art of the Body : rhythmic exercises for health and beauty’ 1929.

In addition to exercise systems, the physical culture movement also spawned a host of publications and organisations, such as the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA). All had in common a cluster of ideas relating to personal improvement, nationhood, morality and a redefinition of masculinity in physical terms.

The movement began in Scandinavia and Germany, sweeping the rest of Europe and North America, inevitably making its way to colonial India. The anthropologist Joseph Atler suggests that the development of postural yoga is directly linked to the “reinvention of sport in the context of colonial modernity and also to the increasing use of physical fitness in schools, gymnasiums and public institutions”.

An exercise sequence from ‘The Gymnastic Free Exercises of P H Ling’, 1853.

Ling gymnastics

Pehr Henrik Ling was a gymnastics instructor in the Military Academy at Carlsberg in Sweden. As a tuberculosis sufferer, he found that a daily exercise routine improved his health, and decided to share his experience.

P H Ling, 1839.

Ling attended classes in anatomy and physiology and developed a science-based ‘movement cure’, aimed at treating muscular and nervous disorders. He eventually founded the Royal Gymnastic Central Institute for the training of gymnastic instructors, and after several attempts to interest the Swedish government, his system was taken up by the Swedish military.

Ling's system of large groups led by an instructor to perform repetitions and cycles of postures was a model for many exercise systems to come.

A women's exercise class at the Ling gymnastics centre in Stockholm, 1910.

The Swedish system, as it came to be known, was highly influential in other countries. It spoke to a growing belief that the state shared the responsibility of ensuring that the citizens of tomorrow – children – were mentally and physically fit to serve their country in the future. And so gymnastic and other exercise systems entered the school curriculum.

Translated into economic and political terms, strong healthy workers and soldiers were essential to meet the demands of the industrial revolution and of empire.

The introduction of military drills in the colonial army and gymnastic drills in the anglicised school system also led to greater participation and awareness of physical culture in South Asia.

An exercise sequence from ‘My System: 15 minutes’ exercise a day for the health’s sake’ by J P Müller, 1900.

The Müller System

Jørgen Peter Müller (1866–1938) was a Danish gymnastics educator and author. His book ‘My System’, published in 1904, was a bestseller. His system consists of 18 exercises done in a daily 15-minute routine. The system also includes stretching and breathing routines and a towel-rubbing routine to follow a daily bath.

J P Muller, 1904.

Müller encouraged individuals to use his system in order that they “might have children who are improved editions of their parents”, so rendering “the noblest service to the state” by “raising the level of the race as a whole” (‘My System’, 1904).

A driving force behind the rise of physical culture was a growing concern about the physical and mental decline of humanity. Degeneracy was a term that was widely used to suggest that a particular social or cultural group was in decline or, in the case of Western ‘races’, at risk of moving past their prime.

Fortunately this process was said to be reversible. The hereditary flaws of previous generations could be reversed by better education, exercise and selective breeding. Self-improvement and good health could be aligned with the greater good and national improvement.

Some postures in Müller's system are uncannily similar to modern yoga postures. Mark Singleton notes that the yoga posture ‘the plank’ appears in his system decades before it is seen in yoga systems.

But Müller was also aware of yoga. In his book on breathing he discusses the “Yogi complete breath”, although he finds his own system to be better. His system was certainly known in colonial India, suggesting an exchange of ideas with the emergent modern yoga systems in South Asia.

Cover of ‘YMCA Association Men’ magazine, June 1919, USA.

The Young Men's Christian Association

Muscular Christianity first arose in the mid-19th century in relation to writers such as Charles Kingsley, who advocated a combination of “athleticism, patriotism and religion” (Putney) as an antidote to the negative effects of industrialism. It was an ethos that was taken up in English public schools, the military and the Young Men’s Christian Association.

The YMCA saw exercise as a tool for moral reform and inculcating Christian values – “education through the body, not of the body” (Singleton). Its red triangle logo symbolised the threefold nature of manhood: mind, body and spirit.

The YMCA was active in India from the mid-19th century. In 1919, while teaching and coaching basketball at a high school in Illinois, Harry Crowe Buck (1884–1943) was invited by the International Committee of the YMCA to serve as the Physical Director of the Central YMCA in Madras (now called Chennai), India. In 1920 he opened a physical training school in Madras.

Harry C Buck, c. 1920.

For the YMCA, he devised “programmes and courses which combined Indian and Western physical exercise” and trained the first Indian athletes to attend the modern Olympic Games in 1924.

The YMCA contributed to a new social and moral respectability for physical culture in South Asia, especially among the middle classes and ruling elites. It also reinforced the link between spirituality and physicality, which was a good fit for yoga, with its spiritual roots.

But more importantly for modern yoga, it helped pave the way for physical yoga traditions like hatha yoga to be rehabilitated.

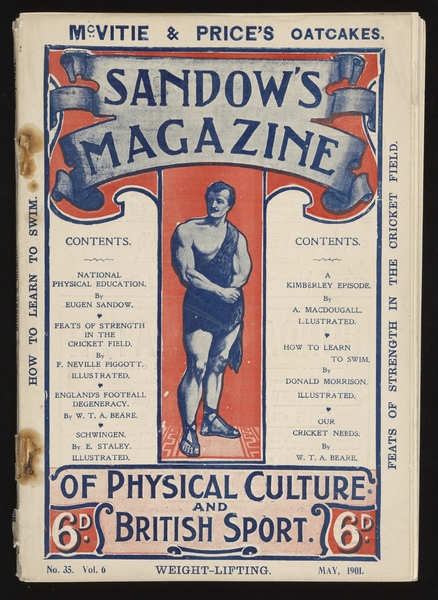

An issue of Sandow’s ‘Magazine of Physical Culture and British Sport’, 1901.

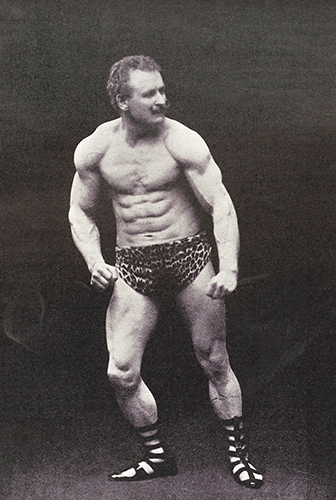

Eugen Sandow

Among the most popular figures in the physical culture movement was the bodybuilder Eugen Sandow. Through tours, lectures and demonstrations, Sandow initiated a worldwide revolution in bodybuilding. His books and popular magazines were infused with similar values to muscular Christianilty.

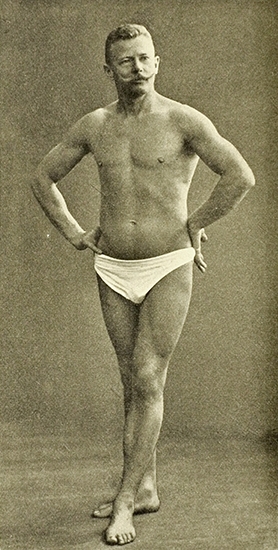

Eugen Sandow posing for his ‘Magazine of Physical Culture’, c.1900.

In 1904, Sandow visited colonial India. He toured the country with a tent that could hold 6,000 people, and was greeted by crowds of every class of society, colonial and native. Thousands were turned away every night (Chapman and Waller).

Asked by one reporter what would happen if Bengal took up his system en masse, he replied “from delicate they will become strong”. And he had plenty of examples to prove it among his Indian followers.

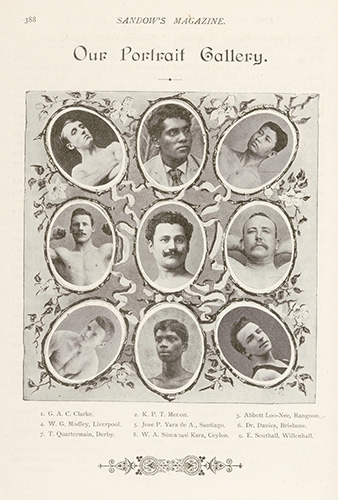

Sandow’s magazine featured exponents of his system from around the world.

His message was notably free of the rhetoric of degeneracy, blaming poor diet and want of exercise rather than innate racial inferiority for any weakness. “The native Indians have a foundation for the building of large physical men,” he insisted. But his message was unintentionally subversive, offering empowerment through the control of your own body.

Bodybuilding as a sport emerged from the theatrical tradition of the strongman, a common feature of fairs and shows (Chow). Thanks largely to Sandow, this manufactured view of masculinity entered the mainstream as a legitimate measure of manhood. Soon every country had to have its own Sandow.

An exercise sequence from ‘Sex Efficiency Through Exercises: special physical culture for women’ by T H van der Velde, 1932.

The Genevieve Stebbins System

In many ways the physical culture systems aimed at women were closer to modern yoga than gymnastics or bodybuilding. The Delsarte method (1811–71), which was likened to hatha yoga by Vivekananda, was supported and furthered by an American woman, Genevieve Stebbins.

Genevieve Stebbins, 1902.

Her book ‘The Genevieve Stebbins System of Physical Training’, 1898, includes chapters on relaxation, breathing and dance-like sequences of exercise ‘drills’.

Well aware of yoga, Stebbins describes how she came across what she calls “dynamic breathing” at a class in London in which “the patients were tired brain workers, some of them Oxford professors; the teacher was a Hindu pundit”. Her system includes an exercise explicitly named yoga breathing, “so called because it is used by the brahmins and yogis of India”.

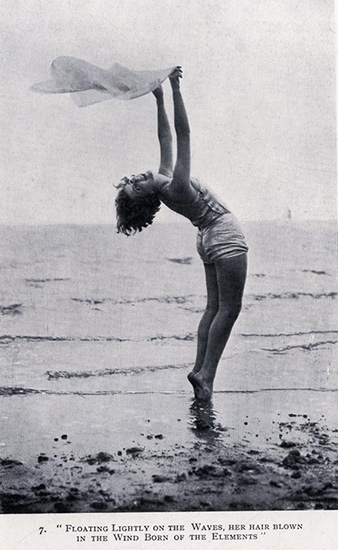

Stebbins's system also had a mystical element, through which a woman could “bring herself into harmony with the great mysterious forces around her and acquire an inner power”.

An image from Mary Bagot Stack’s exercise system. Bagot Stack founded the Women's League of Health & Beauty in 1930, the first mass keep-fit system.

From the 1920s onwards, women’s exercise classes were usually concerned with suppleness, posture and health. So when modern yoga appeared in the West, women in particular were were already receptive to the kind of holistic approach it offered.

The extent to which Stebbins's system and others were influenced by yoga and other non-Western systems is open to debate, but with greater global travel and communication, it’s likely that there was exchange and assimilation in both directions.

The more masculine gymnastic drill and bodybuilding contributed to the revival of physical culture around the world through magazines and publications that helped to transmit both culture and ethos. These publications also provided a blueprint for the exercise manuals and health magazines that are so familiar today.

But perhaps the biggest impact of the international physical culture movement on yoga was that it inspired South Asians to look again at their own physical culture traditions.

About the author

Lalita Kaplish

Lalita is a digital content editor at Wellcome Collection with particular interests in the history of science and medicine and discovering hidden stories in our collections.