Writer David Jesudason traces the stories behind the marks on his body, from healed acne, a large birthmark, and scars from racist attacks. Most are sources of sadness and anger, bringing memories of isolation and self-consciousness, but one scar is a symbol of happiness and hope for the future.

In ‘The Mirror’, Charles Baudelaire asks, “Why do you look at yourself in the glass, since the sight of your reflection can only be painful to you?” Unlike the ugly man in Baudelaire’s poem, I have no answer and yet I still look. I don’t see beauty in my reflection. I see the marks of racist attacks, traumatic memories and a life spent hiding in the shadows.

My mirror shows a lifetime of scars – some from birth, some from childhood and some still raw. Growing up in a small, white-dominated town already marked me out, as I was the only person of colour at school. My parents’ immigrant faith in British fairness and tolerance was at odds with the reality I found in the classroom, playground and street.

Their world view didn’t shift even when I came home crying from primary school after being kicked and punched for looking different. They didn’t want to hear about the vile racism, and so the pain was internalised.

A scar on my cheek from where my face hit the ground was the only visible sign of a troubled life. Inside, feelings of anger, sadness and depression swirled and were often triggered whenever I glanced at this scar, etched on my face like a marooned tear.

Dark skin tends to scar easily and be prone to hyperpigmentation. There’s also a higher likelihood of having scars from birth. While the tear mark on my face was the first scar that was visible to others, the worst remained covered up for years.

Seeing these images for the first time was quite a paradox. I initially found them distasteful and triggering, but when I worked through my emotions I could see their beauty.

My birthmark covers the lower half of my stomach with a large brown ‘splatter’-like blemish due to trapped pigmentation. Birthmarks like this were named the ‘Mongolian spot’ by German physician Erwin Bälz over a hundred years ago. Still calling it a ‘Mongolian spot’ today is perverse, as it’s common in groups of people who aren’t of Mongolian origin – I’m of Malaysian and Indian heritage.

I particularly detested this birthmark when I was younger and hated having to explain it to anyone who saw me unclothed. It’s why I hated swimming, gyms and beaches. It’s why I spent my youth sexually frustrated.

Learning resilience

As I type, I glance at my left hand. A small line marks the web of skin between thumb and forefinger and protrudes slightly. Touching it transports me back to my very first memory, one that is imbued with nostalgia and pain in equal measure.

I am roughly the same age that my daughter is now and full of the wonder the world contains when you’re only four years old. I want to help my mum, and so I carry a milk bottle proudly into the house. The bottle smashes, I pick up a shard and the memory ends.

The scar the shard made is a physical link to this memory and, caressing it, I can instantly feel the same shame I felt as a pre-schooler who had spilt milk. I often touch it when I feel anxious about letting people down or when I’m overcome by a sense of “doing wrong”.

By removing the context of the scarring, the photos feel like an alien terrain to me. I didn't instantly recognise them, and find them enigmatic. I never would have thought something so painful could be so artful.

I also touch this part of my hand when I worry about my daughter. I’m scared that her light-brown skin will be marked like mine but, worst of all, I fret about how her physical pain will manifest. I want to scream when she picks up a glass bottle, but I know she has to experience the world on her terms and learn to be resilient when trauma inevitably arrives.

Because of her I’ve read a lot of parenting books, including many that claim being a toddler is like being a teenager. However, it was during my teenage years that I started to learn to be resilient – I left home at 16, recovered from acne and wasn’t overly fazed by the scars it left behind.

The marks around my face eventually disappeared. A feeling of loneliness remained, though, as friends went on holidays without their parents for the first time and I made up excuses not to follow them, worried that the sun would make all my remaining scars worse.

Holidays were never fun, as my mum and dad were convinced that sun cream was a Western thing. Playing cricket once, I came home burned and the scars looked worse, like they were now seared on.

Our family doctor was untrained in dealing with dark skin, and I remember him being taken aback seeing evidence that I could tan or burn. He said I should try treating my scars with olive oil. Research at the time had been skewed towards white skin and we were his only brown patients. I kept persevering with olive oil and, in those pre-internet days, convinced myself I just had to find the right brand.

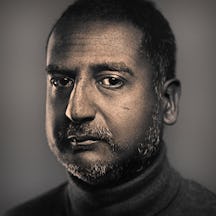

Franklyn Rodgers has eerily captured what it feels like for me to look into a mirror. There's so much trauma associated with my skin that I cannot see what I really look like.

Mental scars

Eventually I gave up trying to heal the unhealable. I was a man with scars and I embraced this with a confidence that would ebb and flow depending on my mental health. However, moving to more cosmopolitan areas didn’t mean the fights and racism stopped.

In fact, ten years ago I was attacked brutally and punched in my eye by a teenager. The surgery left me with a ringed mark around my eyelid, another stark reminder of how violence has blighted my life and the recurring unfairness of it – no arrests were made. The wound now is a relic to racism, a reminder that prejudice leaves its victims with physical and mental scars.

Is it possible to be like Baudelaire’s anti-hero and feel beautiful despite evidence to the contrary? I don’t think so, but there’s one scar I have that I can look at without distaste. It requires two mirrors to see, as it’s on my back, the result of surgery I had after suffering a back injury. The reason I don’t find this memory painful is because the operation was undertaken just before my daughter was born, and it reminds me of all the joy she has brought me.

She and I might scar more easily than most, but we experience life together, sharing any pain not with the mirror but with each other. I may be marked by the traumas I’ve experienced throughout my life, but she is the physical representation of all the joy I have and can look forward to.

About the contributors

David Jesudason

David Jesudason is a freelance journalist who covers race issues for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. He was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023, after his first book ‘Desi Pubs, A Guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food and Culture’ was hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”. David also writes ‘Pub Episodes of My Life’, a weekly newsletter about the drinking establishments that serve marginalised people.

Franklyn Rodgers

Franklyn Rodgers is an artist and creative director whose work explores innovative approaches to re-examining the portrait in contemporary visual culture. His work not only investigates portraiture through narrative, content and context, but also how their placement can open new dialogues in challenging the idea of representation within the language of photography. He has exhibited internationally and his work is held in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery, Tate Britain, Lloyds of London, Welcome Collection, Autograph, Queen Mary University of London and Arts Council England.