When we’re unwell we often have to rely on other people for support, but the balance of power between patient and professional can be uneven. Caroline Butterwick knows the frustrations and dangers of not being heard. Could cutting up old doctors’ letters and reworking them into new forms be a way to reclaim her story? Here, Caroline reflects on the catharsis of creation and proposes writing as a way to take back control.

Writing back to authority

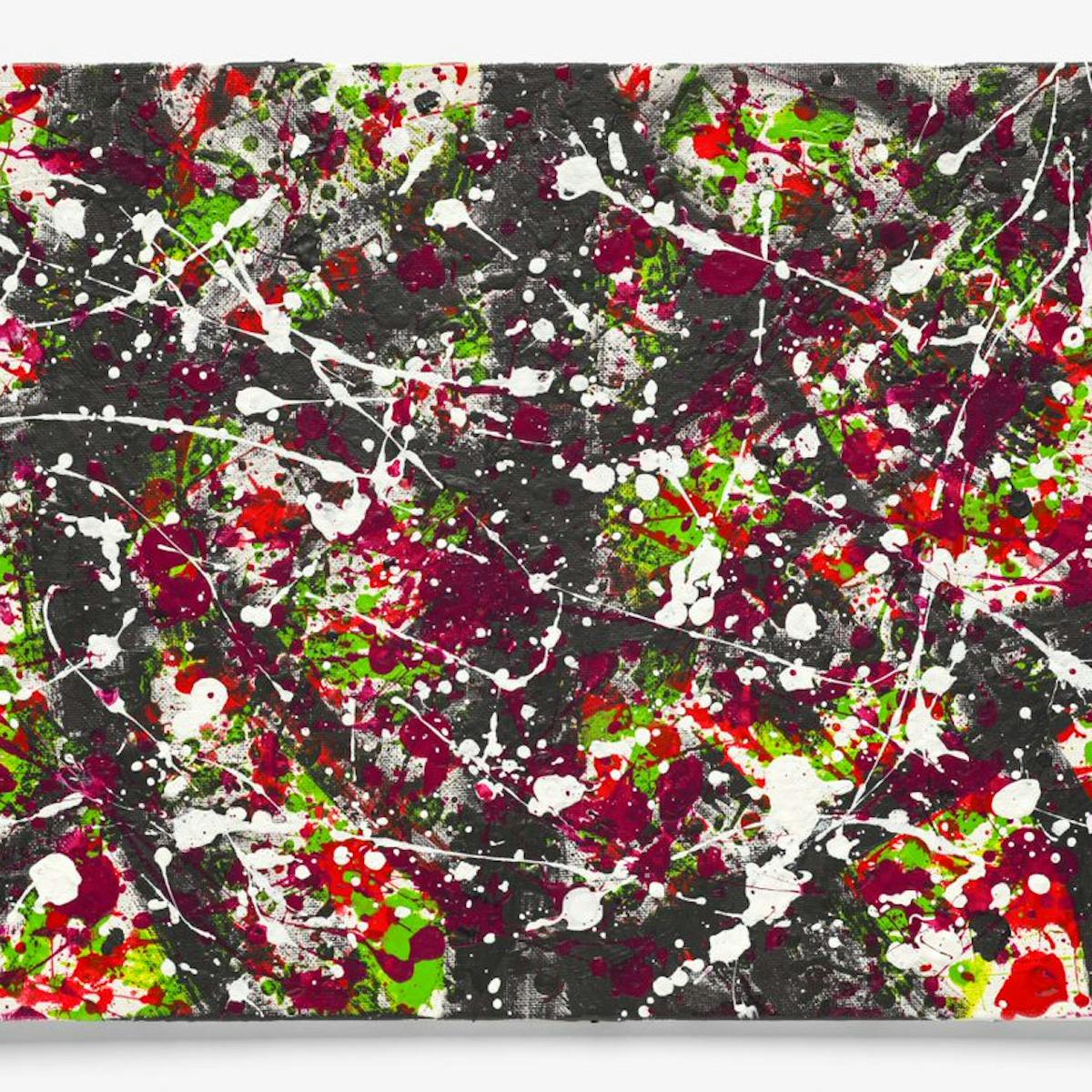

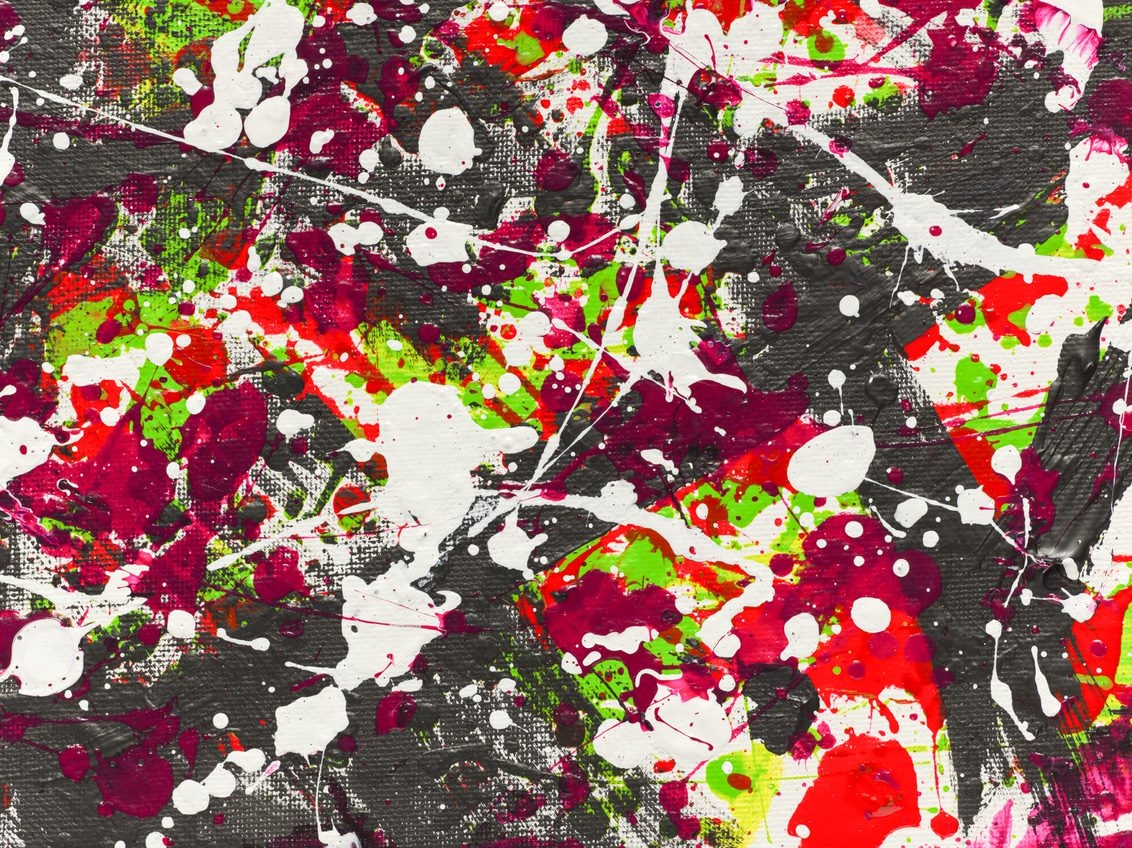

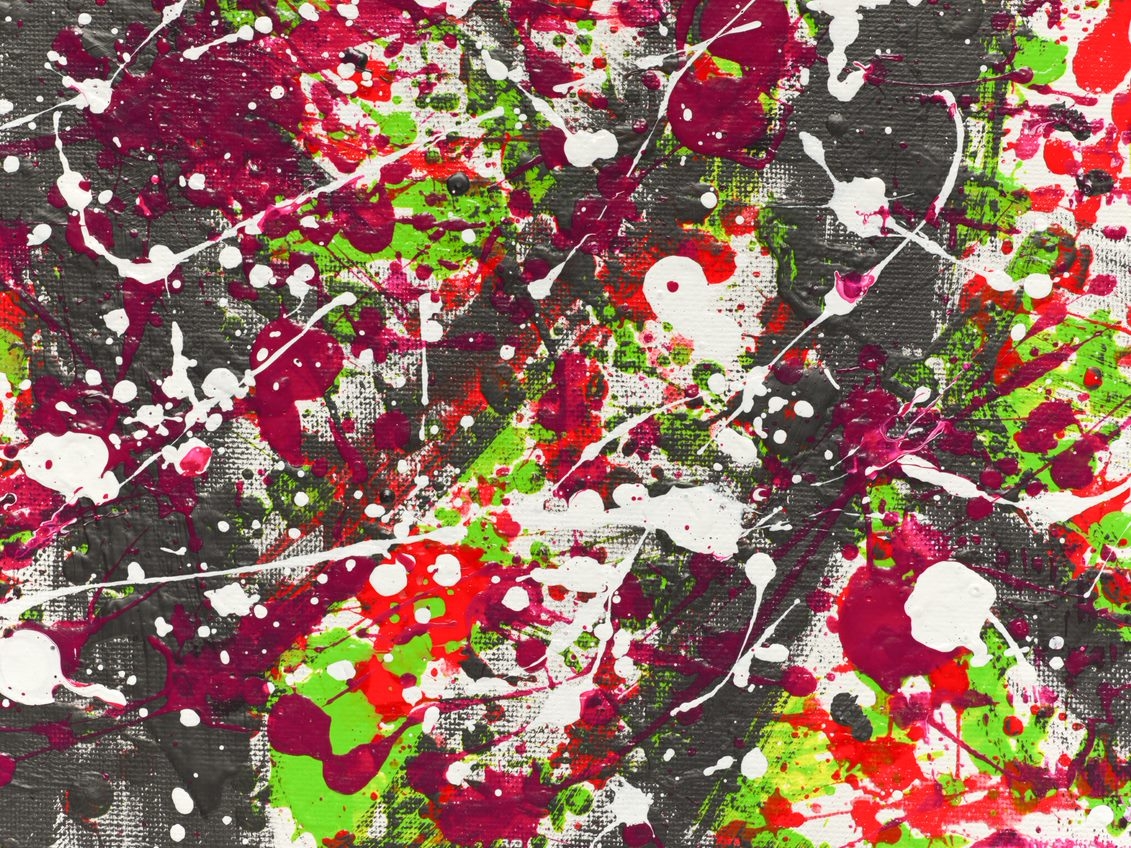

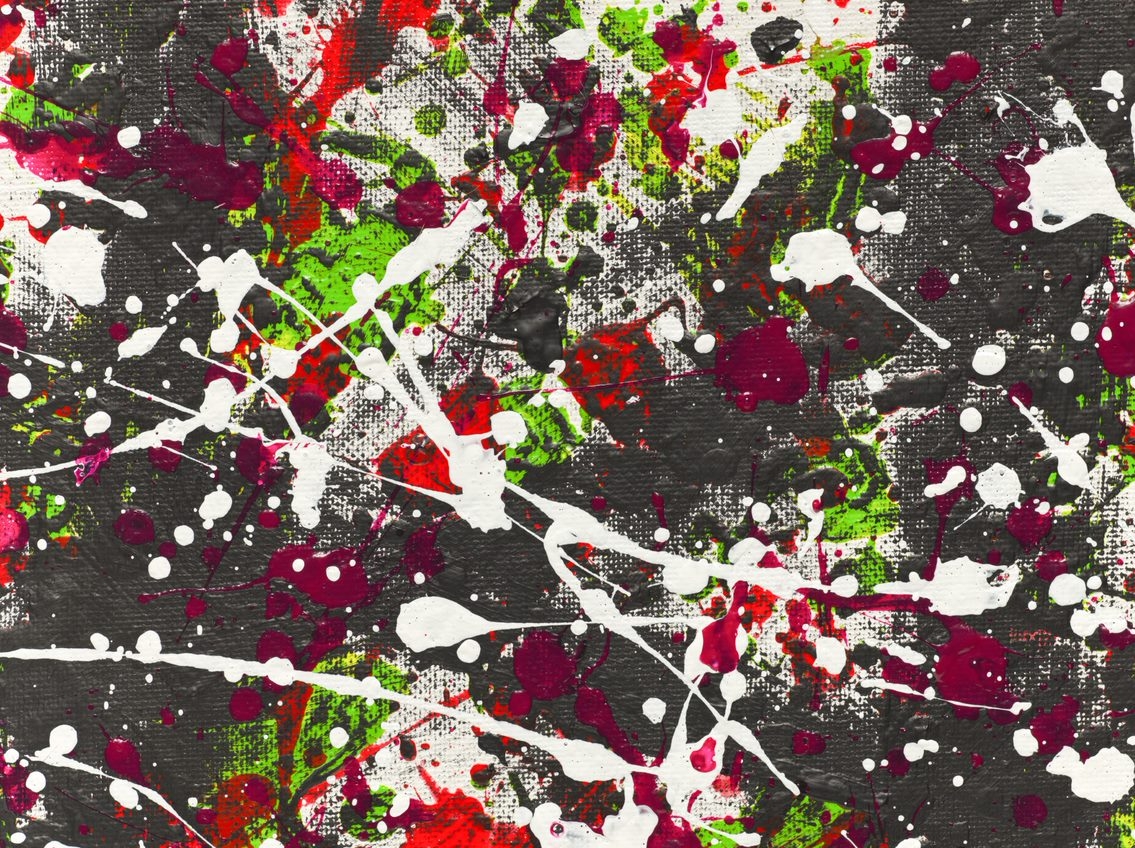

Words by Caroline Butterwickartwork by Kimberley Burrowsaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Article

I know my own life best. Right? I know when I’m low, or anxious, or need help, or am dealing with side-effects of medication. I am an expert in me.

But when using mental health services, sometimes it feels like my voice is the least important. Professionals can meet me for ten minutes and decide that, actually, what I’m saying isn’t the case. I say I’m struggling to cope. That’s attention seeking. I say that the medication you’re prescribing is affecting my eyes. That’s not a known side-effect, so can’t be true.

And, oh, it’s exhausting. And frustrating. And, at times, dangerous. If professionals don’t believe us, we are denied the appropriate support.

It’s something I think about a lot – the power dynamic between patient and professional.

“It’s something I think about a lot – the power dynamic between patient and professional.”

Tidying through my desk drawers the other day, I stumbled upon some old doctors’ letters from when I was most unwell. It was disconcerting. It was strange to read someone else’s account of my life and to be powerless to change what had been written. It felt like the words belonged to a different version of me.

It was strange to read someone else’s account of my life and to be powerless to change what had been written.

I was working on a zine about mental health, so I decided to put these doctors’ letters to good use. I cut out words and phrases and rearranged them on a blank page. Doing this created strange juxtapositions, and highlighted how alien I found the words, but also felt like a kind of reclaiming.

Unwell times needs to engage. Objectively listen to her.

These lines make little sense, and that reflects how I feel about the originals.

Zines and found poetry

Zines are a way for anyone to self-publish their writing and art, and I’ve been into them since I was a teenager. I used to pore over 1990s riot grrrl zines, admiring how they made biting statements about what it meant to be a woman at that time.

‘Per-zines’ are a type of zine that draw on the creator’s personal experiences, observations and opinions. Disability and mental health often feature. The zinester makes a space to share whatever they want about their life, and readers in similar situations feel less alone.

So I made my per-zine about mental health, using these doctors’ letters, and combining my interests in found poetry and the cut-up technique. With both, you take words from elsewhere and rearrange them into something new.

A wonderful example is the poem, ‘The first lines of emails I’ve received while quarantining’ by Jessica Salfia, which captures the strangeness of the marketing emails she received during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. Salfia created her own original art out of others’ words, which reflected her life at that time.

“Sometimes I keep my writing about mental illness secret – something just for me. Often I share it. This can be very exposing, but it feels important.”

I created my own found poems, delighting at how nonsensical they seemed. Diagnosis interview she sleep disturbed. Garden time. Assessment. Meal. Bed. There’s something quite wonderful about the absurdity of these lines, especially when I think about how absurd my life has been when most unwell.

Sometimes I keep my writing about mental illness secret – something just for me. Often I share it. This can be very exposing, but it feels important.

I’ve thought about sending my per-zine to the doctors who wrote the original letters. Would they be confused, or even angry? Would they see it as evidence of illness, of disorder? Maybe it would be helpful – a way for them to see how I feel about my life and the way I’m spoken about, and to address the power imbalance between us. But, so far, I haven’t. I’m worried I wouldn’t get the response I want.

Writing and power

A lot of my writing about mental illness is around the idea of ‘writing back’ to authority. It’s about reclaiming my sense of who I am – that my story matters, that I know myself best.

I think of conversations I’ve had with other disabled friends. There is a lot of frustration at being made to feel you don’t know yourself.

Or, when I was in hospital, meeting other people there who were hurt and angry at how they were talked about. Given diagnoses after a five-minute conversation that was so detached from their reality. Having assumptions made about them.

“It goes beyond just the comfort and catharsis that can come from letting the words flow onto the page. It’s about owning our own narrative again.”

Personal writing about mental health and disability can be a way to make our experiences fully our own. When we feel diminished by the people who are supposed to help us, we can use the written word to challenge or change the dynamic.

Many of us are familiar with the idea of creative writing as therapeutic. But I think it goes beyond just the comfort and catharsis that can come from letting the words flow onto the page. It’s about owning our own narrative again.

With every word I write, I am reclaiming my power. And with every word you read, you’re helping me do it.

About the contributors

Caroline Butterwick

Caroline Butterwick is a writer, researcher and freelance journalist based in North Staffordshire. She’s currently working on a nonfiction book proposal, and her freelance journalism has featured in a range of publications, including the Guardian, the i paper, Mslexia, and Psychologies. She is studying for a PhD in Creative Writing that explores the power of memoir as a counternarrative to dominant models of disability, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council/Midlands4Cities.

Kimberley Burrows

Kimberley is a blind abstract expressionist artist from Salford, Greater Manchester. An intuitive approach to her practice explores the complex themes of blindness, mental health, and art as therapy through performative mark-making. Kimberley is keen to understand the relationship between artist and medium, beyond the scope of vision, and the various health benefits that art can cultivate. Kimberley is a passionate advocate for accessibility and inclusion, which are both at the forefront of her social media presence. Kimberley, who will undertake a Master's degree in painting at the Royal College of Art, London later this year, has been featured in BBC Look North, Manchester Evening News, ITV News, the Daily Mail, and Marie Claire, among others.