Patterns of violent behaviour in families was first seriously studied just over 30 years ago. But addressing and successfully stopping the cycle is another matter altogether, and understanding the nuances of coercive control is central, as Laura Bui learns.

Why do victims become violent?

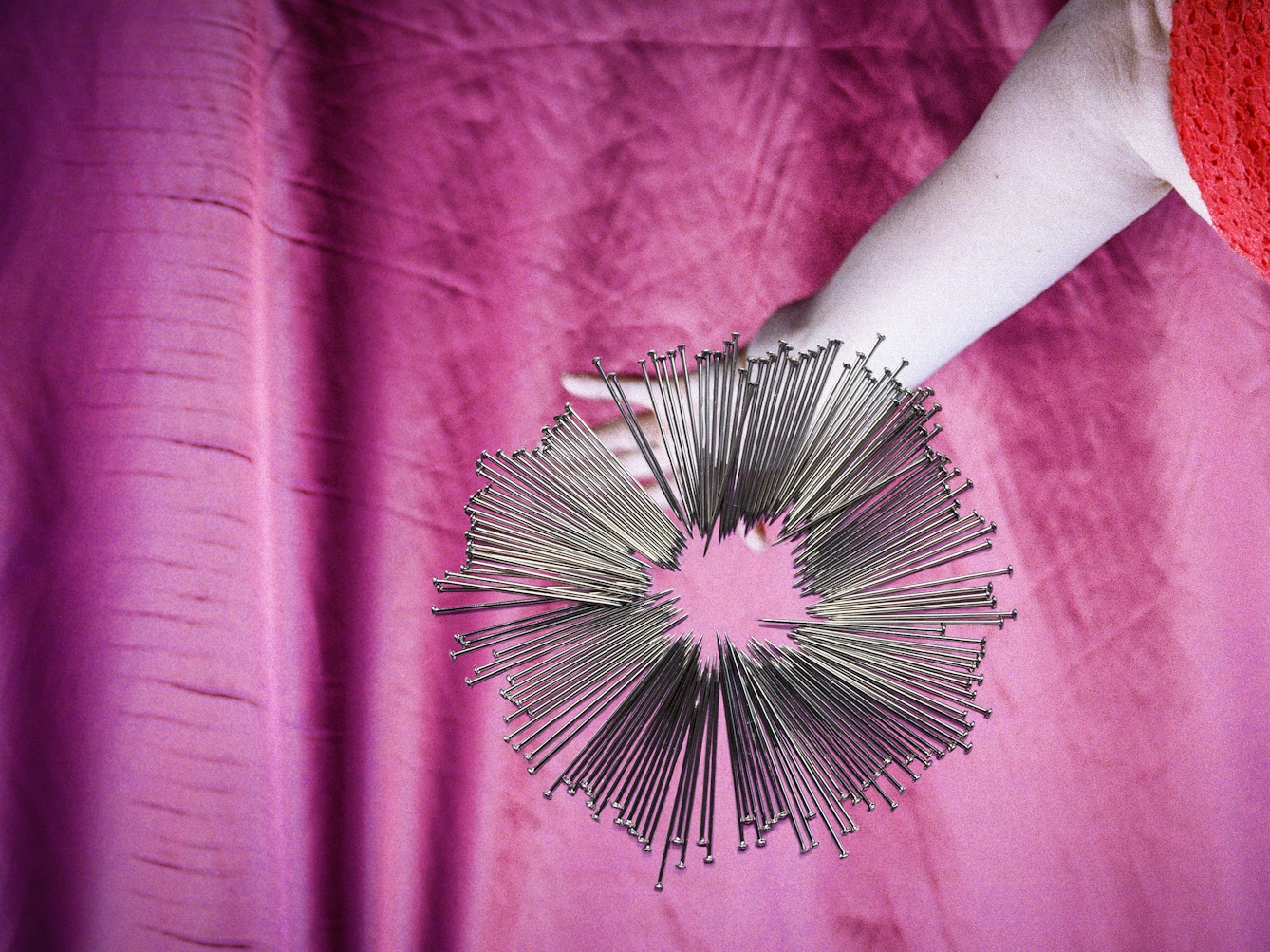

Words by Laura Buiartwork by Jessa Fairbrotheraverage reading time 5 minutes

- Serial

“Family is a pattern,” the writer Yiyun Li remarked in a 2017 interview in the Guardian. Li’s simple observation reveals the power of the past to repeat itself in the future and how, sometimes, we unknowingly become the type of person or perpetuate the dynamics we wish to be free from. The cycle of violence is an example of just this sort of repetition.

The term “cycle of violence” first appeared as the title of Cathy Spatz Widom’s 1989 landmark study of 1,575 individuals who had experienced physical abuse or neglect. She followed them from childhood to early adulthood in the US and found that those who experienced childhood physical abuse are more likely to become violent in the future themselves.

In the 1990s, an update on Widom’s study showed that these children had not only higher risks for violence in adult life, but also for a host of negative life outcomes, from mental health issues to low levels of achievement.

The merits of early intervention

Commissioned by the US Department of Justice, the second study’s findings highlighted how serious the problem of child maltreatment was. One of the report’s recommendations was to “intervene early” – to identify this victimisation and to do something about it as early as possible, because intervening later would make it more difficult to reduce the damage done.

“Cathy Spatz Widom’s 1989 study found that those who experienced childhood physical abuse are more likely to become violent in the future themselves.”

Early intervention and, ideally, prevention, recognises that change is harder in later years when patterns of behaviour and being solidify. It provides a remedy to a repetition that seems entrenched and inevitable. Perhaps this difficulty is what Yiyun Li sensed when she added the fatalistic: “I’ve looked at it all my life, and I can’t change it.”

The victim becomes the perpetrator, the sufferer goes on to inflict suffering on others. And so on.

Another way of understanding the cycle of violence is that one generation’s violence is inflicted on the subsequent generation. The victim becomes the perpetrator, the sufferer goes on to inflict suffering on others. And so on.

Coercive control in relationships

North Yorkshire, where the market town of Northallerton and the cathedral city of York lie, is the region Amy Marshall oversees as part of the police’s work of addressing domestic abuse. Marshall wanted to understand how people became victims in abusive relationships and what motivated perpetrators to behave abusively. An optional module at university on domestic abuse led her to pursue her role with the police, first as an officer and coordinator, and then as a safeguarding manager.

“Witnessing violence in the home is enough to cause a child to become an adult perpetrator towards an intimate partner.”

When we speak on Zoom one summer evening, I ask Marshall whether she has witnessed the cycle of violence first-hand. She says that she gets asked that question a lot. She only deals with the immediate dynamic – that of the victim and perpetrator – and the term “cycle of violence” in her line of work is mainly understood as the “power and control wheel”, a tool practitioners use to make sense of the abuse.

But she does, from time to time, glimpse the aftermath of abusive relationships through colleagues’ news and notes. She reads assessment reports on how seeing a parent abused has affected children – often they present low self-esteem and develop problems in forming healthy relationships, which reflects the profound loneliness they endure. Or cases when an abuser threatens to murder the children of the person they abuse, and in some tragic instances, actually do so.

Abuse, Marshall points out, is often understood as only physical. When trying to identify violence, officers look for visible signs on the victim, like bruises, marks and cuts. Actually, it is the controlling behaviour – name-calling, humiliation, social isolation – that is the significant characteristic of such relationships, though this is often overlooked.

Marshall refers to the work of Jane Monckton Smith, a professor and former police officer. Smith’s work highlights invisible forms of violence, called coercive control. This may not produce physical signs of abuse, but can lead to murder, as Smith’s eight-stage homicide timeline demonstrates.

“Abuse is often understood as only physical. When trying to identify violence, it is the controlling behaviour – name-calling, humiliation, social isolation – that is often overlooked.”

The power of the past

“Why do you need that control?” Marshall asks repeat perpetrators. In her experience, none have admitted to having controlling behaviour. They mostly refuse to believe or are in denial that their behaviour towards their partners is abusive.

Marshall doubts that therapies like anger management would help, because anger doesn’t seem to be the cause of their violence, rather a symptom of an underlying issue that they cannot or will not admit.

Victims tend to describe their relationship with the perpetrator to Marshall as “walking on eggshells”. They have to constantly consider any possible repercussion to their decisions. For example, if an argument is likely to happen after going out to see a friend, they will not do so; eventually, they become socially isolated.

As corny as it may sound, Marshall just likes helping people. She exudes this characteristic. When I ask her what motivates her to continue in a role that must sometimes be very difficult, she says she wants to be involved in work that protects vulnerable people and that tries to make a positive difference in their lives.

And then she says, a little embarrassed, as if it is predictable, maybe it is her way of helping her past self, when she didn’t feel like she could ask for help. But I don’t see anything embarrassing about this: the past does have a powerful effect on the present and, if it is allowed to, on the future as well.

About the contributors

Laura Bui

Laura Bui teaches and researches crime and violence at the University of Manchester. Her research on these topics has appeared in academic journals and also in places like the literary anthology ‘Test Signal’, where she explored grief and the paranormal; the non-fiction journal ‘Tolka’, where she questioned what a (criminal) psychopath is really for; and BBC Radio 4, where she raised the questions we should really be asking about true crime.

Jessa Fairbrother

Jessa Fairbrother is an award-winning artist concentrating on themes of yearning and the porous body. Initially training as an actor, she later completed an MA in Photographic Studies, amplifying her knowledge of how artwork and audience collide. Jessa uses embroidery, performance, photography and writing in her work. The artist’s book of her work, ‘Conversations with my mother’, is held in collections including Tate Britain and the V&A, London. Her companion piece, ‘Role Play (Woman with Cushion)’, is part of ‘Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood’ – a Hayward Touring exhibition curated by Hettie Judah.