During a routine dental check-up aged 12, Jasmine Owens was surprised to be offered free cosmetic surgery. It wasn’t medically necessary, but the dentist thought it would improve their looks. Here they explore dominant beauty ideals, who decides what is attractive, and how these judgements objectify children at a vulnerable time in life.

Recently I caught myself worrying that face masks had turned me into an accidental catfish.

Traditionally it’s selfies taken with a filter, from a specific angle, that lead to claims of catfishery. As masks cover up the part of my face I’m nervous about, showing just the good bits to strangers, they feel like a real-life filter.

I didn’t feel self-conscious about my chin until age 12. Before then school friends did call me Chinosaurus Rex and the less original Chinny Chin Chin, but in a teasing way that made me feel special rather than criticised.

It was my dentist who made me think about it seriously. He said my upper and lower jaws didn’t match, and offered surgery to fix it.

“What would the surgery be for – is my jaw going to cause health problems in future?”

“No, it’ll probably never cause health problems.”

I’d only gone for a check-up. My teeth and gums were great, but I’d failed a surprise exam on facial attractiveness.

“Is it just to change how my face looks?”

“Yes.”

I’d only gone for a check-up. My teeth and gums were great, but I’d failed a surprise exam on facial attractiveness.

Twelve-year-old me snapped back, “Why would I want it, then? No.”

I didn’t speak about that conversation for 15 years.

“How could my dentist offer surgery just to change my appearance, when the NHS website said it only rarely provides cosmetic surgery for ‘psychological or other health reasons’?”

Beauty standards in NHS dentistry

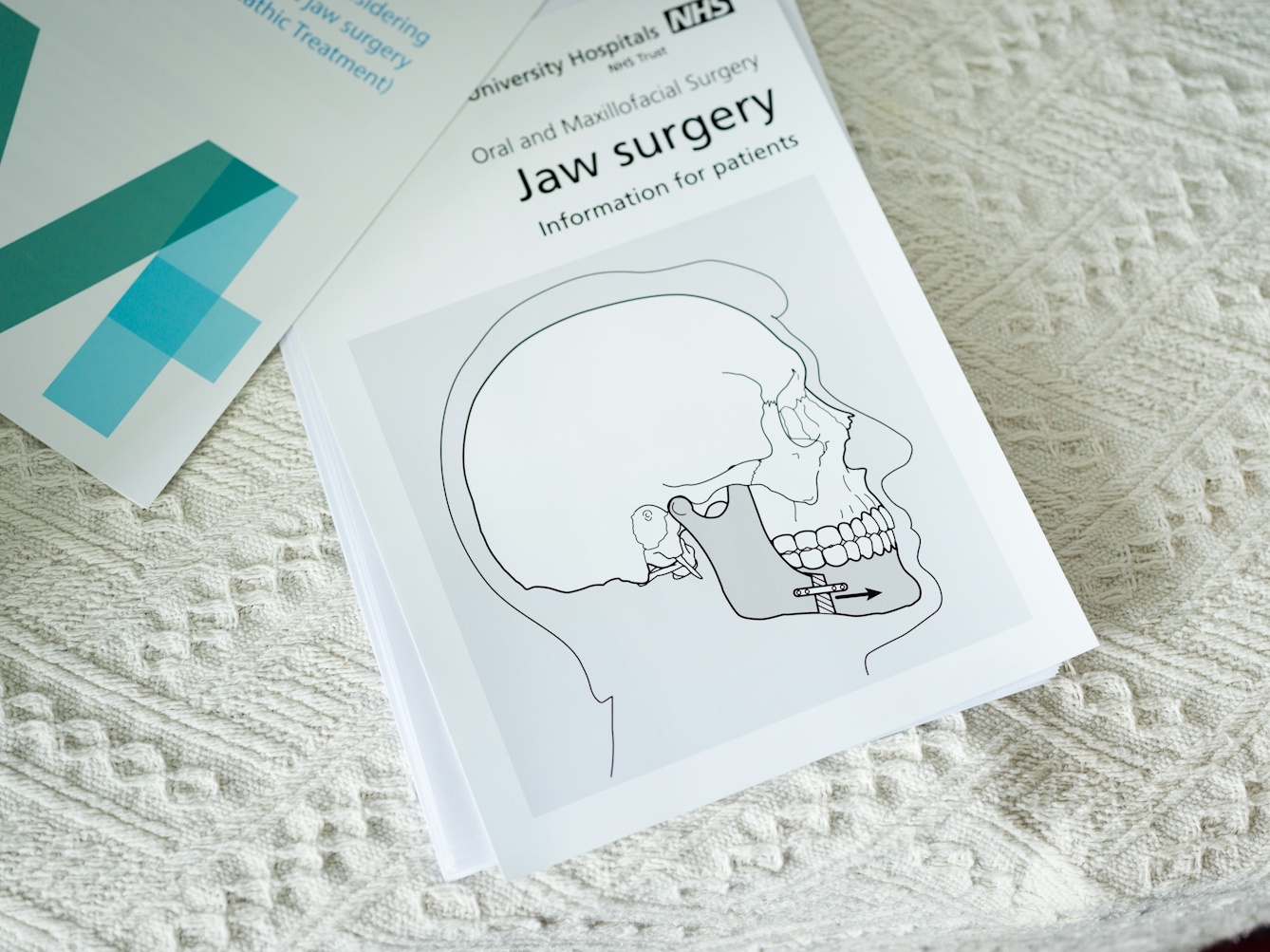

Jaw surgery involves years of braces, a two-to-five-hour operation, significant time off school or work, and lifelong retainers. Many patients report permanent loss of feeling in the lower half of their face after surgery.

How could my dentist offer surgery just to change my appearance, when the NHS website said it only rarely provides cosmetic surgery for “psychological or other health reasons”?

The NHS uses the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN) to assess whether under-18s are eligible for treatment. This involves two components, the first being the Dental Health Component (DHC) which grades mouths from 1 to 5 (1 described as “almost perfection”). The second is the Aesthetic Component (AC) in which patients are scored on a scale of “dental attractiveness” from 1 to 10.

The AC was developed through asking six “non-dental judges” to rate the attractiveness of 12-year-olds based on their photographs. The DHC is said to measure “dental health and functional indications for treatment”, but it too is mired in aesthetic values, containing criteria such as teeth being out of line or protruding, both of which typically cause no functional problems. Children scoring 3 or more on the DHC and 6 or more on the AC are eligible for treatment – even if they have no health problems.

Dr Rizwana Lala, dentist and public health consultant says, “There are very few purely functional reasons for orthodontic treatment. Most children receive orthodontic care for aesthetic/cosmetic reasons.”

“Some people are happy having facial differences, but they can be problematised by medical professionals as something to be fixed. The IOTN was developed by a tiny group of white academics based on what they considered to be acceptable facial and dental features amongst a group of schoolchildren in London. It’s a very narrow, Eurocentric beauty ideal.”

“Whether we look different from birth, childhood or adulthood, when is it in our best interests for medical professionals to intervene?”

Did my dentist really believe breaking my jaw to build back better was in my best interests?

According to Lala, it didn’t matter what he thought – if a child is eligible for treatment, the dentist must inform them. Not doing so would be considered inadequate care and could even lead to negligence claims.

Plastic surgery and informed consent

During a therapy session, I shared the story of my trip to the dentist for the first time.

I was both saddened and comforted to discover my therapist, Sarah Edwards, had been offered unsolicited cosmetic surgery as a child too.

Aged nine, she was offered skin grafts for indentations and scars on her leg. “NHS professionals recommended plastic surgery, so I’d ‘look better in a bikini or short skirt’ and because I ‘might want to become a model’. Even at that young age, I knew I didn’t want to be put through even more surgery for a non-medical issue. I just wanted to be left to get used to my life and identity with the scars.”

Whether we look different from birth, childhood or adulthood, when is it in our best interests for medical professionals to intervene?

The power imbalance can make it hard for patients to say no to medical professionals, creating prime territory for consent issues. As Lala highlights, the unclear boundary between healthcare and beauty further blurs the line of consent.

The General Dental Council (GDC) standards state that consent is an ongoing process and patients can say no at any time. It also says “you must provide patients with sufficient information” in order to obtain consent.

Edwards states, “How can young people provide informed consent if they’re not made aware of other voices outside of dominant beauty ideals? Cultural, societal and family scripts about attractiveness bias should be brought to their awareness.”

“As my mask comes off and asymmetrical face comes out, I remember the non-medical experts who’ve made me feel good enough.”

The 'ideal' smile

Being eligible for free surgery, let alone cosmetic surgery, is a privilege in a world where many people can’t even access essential medications. And I wish more people who would benefit from cosmetic surgery for psychological reasons could access it.

Disclaimer aside, all health issues deserve attention, and low self-esteem is a mental health issue that can be triggered through unsolicited negative comments on appearance.

Some people are impacted more than others by narrow conceptions of the ideal smile, face or body. Lala calls the dentistry system, from braces to surgery, “highly racialised and ableist”, adding “the whole culture needs a rethink”. She says for people with disabilities, sometimes the alleged ideal smile simply isn’t attainable.

Objectification, or having your appearance commented on by someone who doesn’t seem to consider the impact they are having on your feelings, can be especially damaging for gender nonconforming people. In general life that’s unacceptable behaviour – when that dynamic is reproduced in a medical setting, it can trigger the same feelings of being objectified.

Though the British Orthodontic Society (BOS) calls the IOTN “objective and reliable”, the experiences of patients on the receiving end are subjective and varied. I asked BOS if the IOTN standards had changed much since they were first developed in the late 1980s, but didn’t receive a response.

Self-image in the age of Instagram

Instagram banned “plastic surgery filters” in 2019, though filters for bigger lips, higher cheekbones, thinner waists or smaller pores are easy to find. Though it’s not (yet) a medical term, “selfie dysmorphia” is entering the popular lexicon, as people’s mirrors don’t match their selfies. While social media plays a role in setting unattainable beauty standards, it’s not the only source.

When irrationally nervous that someone might yell, “Catfish!” as my mask comes off and asymmetrical face comes out, I remember the non-medical experts who’ve made me feel good enough. I recall catching up with an ex years later, who said, “You still have the exact same face,” like it was a good thing.

I think of a friend’s response when I said I was writing this article: “Obviously this goes without saying, but you know there’s nothing wrong with your face, right?”

About the contributors

Jasmine Owens

Jasmine is a writer and researcher currently working at Ethical Consumer magazine, covering topics such as boycotts, Spanish supply chains and veganism. Jasmine is a fan of excessively long walks and feeding banana to rescue guinea pigs.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.