When you’re displaced, your home is taken from you. How can you begin to form your identity? Novelist JJ Bola, who came to the UK as a refugee in the 1990s, tells of the painful mental toll this takes and how you can begin to survive.

We are from here, but not from here

Words by JJ Bolaaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Article

I am a refugee with a British passport.

Many will see this as a contradictory, and possibly question how such a statement could even exist. It is like saying you are both hot and cold at the same time, hungry and full, dry and wet. Is this possible? Can you have a home and be homeless at the same time?

This statement is a question of belonging, and for most people, you either belong or you don’t. However, for refugees and displaced people, it is tacitly true that you are both, and sometimes neither.

I came to the UK with my family as a young boy in the early 1990s, as refugees fleeing political violence in then Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo). I spoke no English, started school pretty much straight away, and made friends mostly by playing sports and through shared childhood silliness and laughter (the universal language).

At school we ate fish and chips, at home we ate pondu and kwanga. I listened to pop music and Congolese rumba. I wore shirts and trousers, and dashikis and liputas. I participated in both cultures; I lived in both places; I had two homes.

MORE: How a city lives inside you and changes the way you feel

As I got older, I was increasingly asked the question, ‘Where are you from?’ If I replied, ‘London,’ it would often be followed up by, ‘No, but where are you really from?’ This unanswerable question made me realise how I was slowly being pushed out of one home that I had come to know and be comfortable in, and how far away I was from another home that I was forced to leave behind.

The poet Ijeoma Umebinyuo, in her poem ’Diaspora Blues’, writes:

so, here you are

too foreign for home

too foreign for here.

never enough for both.

I often felt like this, existing somewhere in the in-between; knowing you have left and not sure if you can ever really go back, yet never arriving. It is a feeling that is much more intangible, because you feel like you are moving towards something, but you don’t know if or when you will ever arrive. A split between the person you are and the person you are trying to be; a tearing of your identity right down the middle.

The displacement that leads to placelessness

When you are displaced, you are pulled away from your loved ones, family and relationships, but also from your environment; from the places you live, and work, and shop, and go to school. In my novel ‘No Place to Call Home,’ I wrote:

A city is merely a collection of buildings,

and buildings do not have souls,

so how can home haunt you as though a ghost?

In the new place you arrive, you don’t have the same relationship with the places, the buildings and the people in them. And so you try to build new relationships with the city, the buildings; but every now and then you will be reminded of the old, your old city, the one you once knew; this is where the haunting comes in.

You think about the zandu instead of the market, about the terrain instead of the playground, about Bandal, where you used to play, instead of your local borough. It is as though you are abandoned in a permanent nostalgia; as though there is a hologram of another city in front of you, as you walk through the city you are currently in.

But, just like memory, it slowly fades. This burden, this tension and fraught feeling that occupies displaced people can be a painful mental weight. This is no surprise, as research suggests that depression and anxiety are the most prevalent mental health disorders among refugees and displaced people, as well as post-traumatic stress disorder.

On the surface I was able to perform and participate in society, much like everyone else, and do what was expected of me. Beneath all of that, even until now, I felt the push and pull of this placelessness, of having nowhere; nowhere to go, and nowhere that understands you. But how does being forced out on one side and rejected on the other make you feel? For me, it was troubling.

I used poetry and storytelling to help figure out my reality of displacement, and to understand my feelings.

Using poetry and storytelling to find belonging

Writing was a way out of this mental strain and difficulty. I used poetry and storytelling to help figure out my reality of displacement, and to understand my feelings. My debut novel ‘No Place to Call Home’ was published in June 2017. It traces the story of a family that flees political violence and resettles in London. In the epilogue, I wrote:

home should never break you in two,

so wherever you go you are never whole;

half of you remains where you left it,

and the other half is rejected where you arrive.

This is the totalising effect of displacement: a shattered mind, a schizophrenia. When you are constantly referred to as “refugee”, or reminded that you are not “from here”, or to “go back to where you came from”, any label or statement that reminds you that you are not from a place leaves you feeling like you are less of a human being – less a person and more a thing.

Which environment do we claim as ours, if we do not have a place? What is truer is that we are a product of our memory and our imagination; we are affected by the physical and beyond the physical. That we are made up of memory; what we remember of ourselves, the places we come from; our homelands, the dreams of our mothers, fathers, grandparents, elder aunties and uncles, and their memories too.

More people should relate to the refugee experience; is theirs not the living embodiment of the human question? The desire for belonging that we all feel in our lives? As I said in ‘No Place to Call Home’:

That deep inside the hearts of each and every one of us,

we are all always reaching, for a place, that we can call home.

About the author

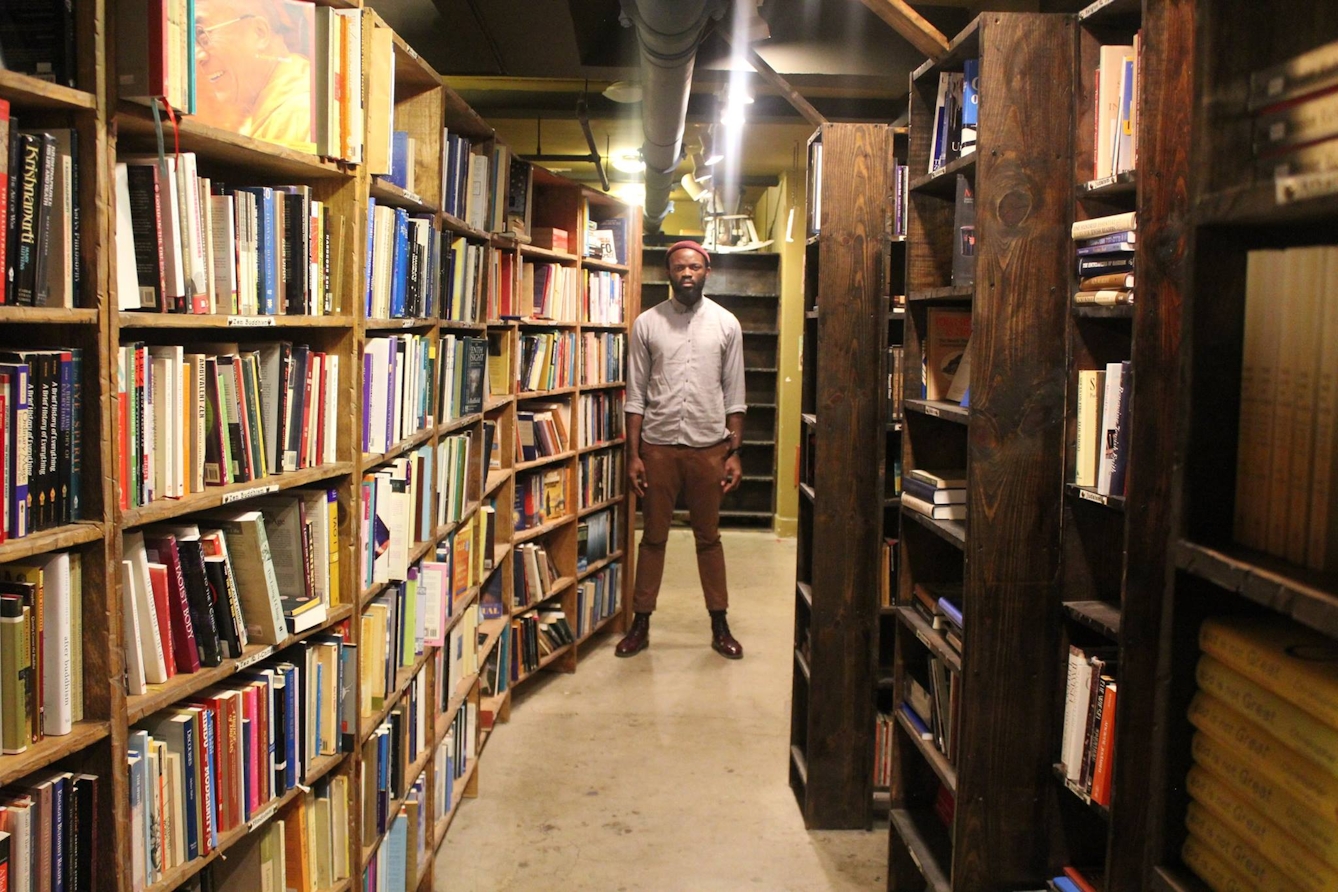

JJ Bola

JJ Bola is an established writer, educator and poet of three collections: ‘Elevate’ (2012), ‘Daughter of the Sun’ (2014), and ‘WORD’ (2015). His debut novel ‘No Place to Call Home’ was first published in the UK in 2017. He was one of Spread the Word’s Flight 1000 Associates in 2017, and a Kit de Waal Scholar on the MA in Creative Writing course at Birkbeck, University of London.