For Hannah Dines, the pandemic has revealed the extraordinary efforts of an unconventional friend on the vaccination frontline. Doctor Jane Harvey’s pioneering approach to monitoring and maintaining the health of those her practice takes care of has extended to her determined coronavirus vaccination work.

It’s the week before Christmas, 2020. In a chilly car park beside a shut-down swimming pool in Greater Manchester, Dr Jane Harvey stands, needle at the ready, resplendent in an orange Puffa jacket and sea-themed face mask. Jane is clinical director of Hyde’s Primary Care Network, a practising GP, and now the manager of one of the UK’s most successful “drive-through” vaccination centres.

A woman who has been shielding is talking the hind legs off a taxi driver through the intercom of a wheelchair-accessible cab. A man, cosy in a bright blanket with tinsel round his oxygen canister, presents his arm for vaccination. An 80-year-old dressed as Santa drives through on his electric scooter.

After she’s given each person their coronavirus vaccine, Jane checks the road is clear and waves them off, lowering her mask and smiling her goodbyes. All is calm, but the workload is tremendous.

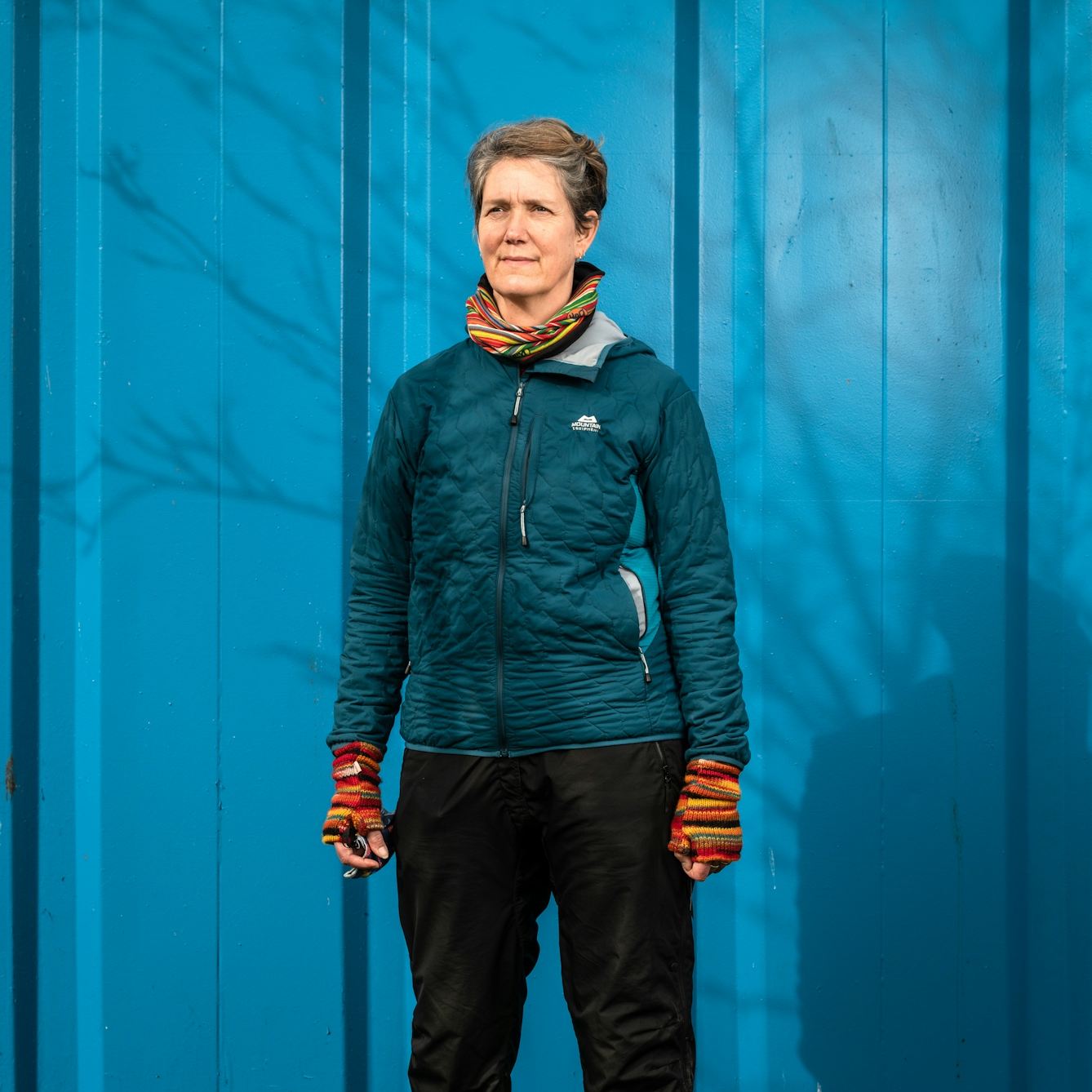

Dr Jane Harvey, clinical director of Hyde’s Primary Care Network, a practising GP, and now the manager of one of the UK’s most successful “drive-through” vaccination centres.

When an unscheduled delivery of vaccine arrives on New Year’s Eve, Jane and two colleagues leap into action. They are so low on staff that they rope their families in, too. Anyone who can convince their teenage children to spend New Year’s Day holding boxes of vaccine has my full respect.

Jane is a family friend and I know her well, but it took a pandemic to make me appreciate the extent of the work she’s been doing. She’s a renegade GP, what they call a “social prescriber”. She prescribes beyond the pill, collaborating and sharing funds to tackle health inequality.

“I think if you ask most healthcare workers why they joined the NHS, they will say because they want to help people,” says Jane. “That’s what medicine is to me: not just prescribing, but facilitating how people want to live, no matter where you were born.”

Vials of the AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine are stored and prepared in the kitchen of Hyde Leisure Pool, ready to be administered to patients in the vaccination drive-through, located in the car park.

Creating a caring network

More than a decade and a half ago, Jane and her husband Tim, who is also a GP, started to work with other local surgeries in their area to tackle a particularly high mortality rate. If you are elderly with dementia, poor and in hospital, you are more likely to die than someone who is elderly with dementia, rich and in hospital. Jane explained that Hyde is within Tameside and Glossop Clinical Commissioning Group, one of the top three places in the UK where older people with dementia are put in hospital, no matter the ailment.

Hyde’s eight neighbourhood practices hired a team – a community matron, complex care nurses and a practice manager – to work with individuals and families to listen, plan, connect and integrate medical care. I asked Jane why this wasn’t the standard in the UK.

“General practices are just small businesses and there’s still a lot of red tape,” she explained. “I found myself among like-minded people who just get things done, but in 2007 we were seen as quite anti-establishment.”

What enabled them to become a primary care network before it was a structure formally supported by the NHS? “We pushed ahead, but anyone could’ve done it. It’s having the bravery and the foolishness to spend the money and say, ‘What’s the worst that can happen?’ Do something to see if it helps, and if it doesn’t help, never mind, at least we tried.”

The Healthy Hyde team is helping. They were awarded Primary Care Team of the Year by the British Medical Journal in both 2016 and 2020 for assisting patients to stay in their own homes, reducing hospital admissions by 19 per cent in 2019.

Patients queue in their cars at the vaccination drive-through, waiting to receive their dose of a Covid-19 vaccine. Hundreds of doses are given at this centre in a day.

The challenges of vaccine administration

Freed from the tyranny of unnecessary hospital trips and given choice of care, the elderly with dementia suddenly had it all taken away. As did Jane. Overnight she went from phoning families about long-term care plans to discussing “do not resuscitate” orders in case they caught coronavirus.

The pandemic has been a terrible blow, massively affecting how the Healthy Hyde team cares for its community. Tameside recorded the highest proportion of coronavirus deaths in the UK.

“We sat down in May just after the first wave and we were very anxious about how we were going to do our flu vaccinations,” recalls Jane. “The drive-through [model] was great for the very frail or those with mobility issues who can’t walk through a huge building and out again in freezing conditions.”

“It was a more flexible set-up for people with learning disabilities, too, as well as generally efficient for everyone. They could be in their own car with their own family. If they were agitated and it wasn’t the right time, they could drive around and come back.”

Doctors like Jane don’t rush in to save the day; they see the day coming, plan carefully and get others to help.

Vaccination drive-through

Pam Lorne: “I wanted to have the jab. I've got an 81-year-old mum and I’ve got grandchildren. In Manchester we’ve had it pretty hard; 300 out of 362 days we’ve been in lockdown. This is what the scientists have been struggling to find; we’ve got it – now we’ve got to use it, because otherwise it just doesn’t make any sense.”

Philip Stafford: “In 2017 I was diagnosed with chronic bronchitis and COPD, and I’d been missed off the list because they thought I’d just got asthma. As soon as I pointed that out, they sent me an appointment text.”

Susan Benn: “My husband and I both got Covid back in March; fortunately we didn't go into hospital. We’re just grateful to be here, really – so many people aren't. This vaccination process has been perfect. To say there’s so many people going through, you’re still treated like an individual – they’re doing a grand job.”

Kevin Brown: “I’m right up for it [having the vaccine]. I’m that generation who’s had vaccines from an early age. I think people who don’t have it are selfish. I’m not really doing for myself – the whole world needs it. The sooner everybody gets it, it’s a safer world for everybody... get it when you’re offered it!”

Caroline Batey: “I've got a disabled son who’s just about to turn 20 who was told to ‘shield’. I’m his main carer. It’s a big relief I’ve had the vaccine. We’ve been shielding for so long you forget what normal is, and to think we are going forward in the future, and we can actually start stepping feet out of the door, is just a massive big welcome.”

Christina Hicklin: “This vaccination centre had been very convenient, only about a five-minute taxi ride. The system has been very efficient, like driving through the drive-thru, but no burger! I just think everybody should have it [the vaccine], to protect everybody else – it’s the responsible thing to do.”

With a successful seasonal flu campaign under their belts, Jane signed up to be among the first wave of GPs to administer the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, but it was more challenging than expected.

“Cohort One were care-home residents, but we were told we couldn’t take it into care homes. We were told we couldn’t move it at all, not put it on a trolley or walk upstairs with it. It begins to defrost as soon as it’s sent and you have five days to use it all, including the two it spends in transit. We were told this a couple of days before we had to start vaccinating. It was really hard.”

By 7 January this year, their small team had given over 3,000 Covid-19 vaccines. The drive-through was so efficient that 1,000 of those were second doses, administered before the UK government ordered that second doses should be delayed. Jane says she was told unequivocally to stop giving second doses or else.

"By 7 January this year, Jane and her small team had given over 3,000 Covid-19 vaccines. The drive-through was so efficient that 1,000 of those were second doses."

Soon after this, Jane and the head of her clinical commission, Jessica Williams, were on the radio. They spoke eloquently about the exhausting, rewarding nature of it all, but Jane cried when asked to talk about the distressing conditions in care homes, the very ill unable to see their loved ones. She cried on behalf of all of us.

Doctors like Jane don’t rush in to save the day; they see the day coming, plan carefully and get others to help. Their name doesn’t go down in history, and the people they save just drive home and put the kettle on.

At the end of March, I phone Jane to see how she’s doing. She and Tim have been vaccinating all day and have fallen asleep on one another on the sofa. “If we can vaccinate all nine cohorts, that’s 99 per cent of deaths from Covid-19 reduced. Not far now,” she says.

About the contributors

Hannah Dines

Hannah Dines is a contact tracer, writer and Paralympic trike racer anxiously waiting for the Tokyo Games to be confirmed.

Robin Hammond

Robin Hammond has dedicated his career to amplifying narratives of marginalised groups through long-term photographic projects and is the winner of many prizes. His work on discrimination against the LGBTQI+ community around the world, ‘Where Love Is Illegal’, has been featured in publications including Time Magazine and National Geographic. Robin is the founder of Witness Change, a non-profit organisation dedicated to advancing human rights through visual storytelling.