Darwin’s ‘Tree of Life’ is one of the most famous drawings in the history of science. Ross MacFarlane explores the deep roots of the concept of the tree as a visual metaphor, and how it became entangled with eugenic thinking.

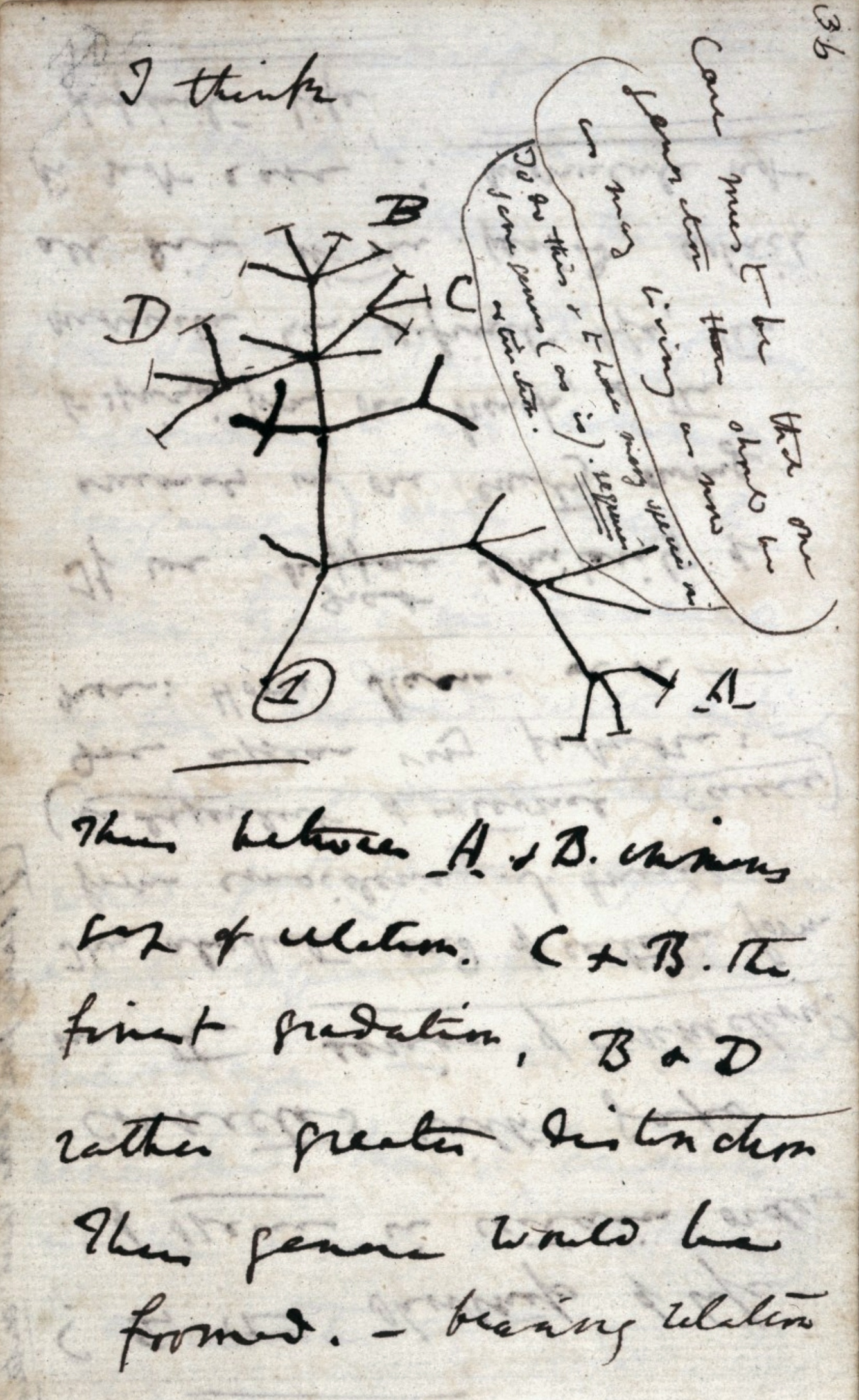

This small illustration, sketched in one of Charles Darwin’s notebooks, is commonly referred to now as his ‘Tree of Life’. Drawn around July 1837, after his return from his voyages on HMS Beagle, it’s seen as the first iteration of him visualising a theory of evolution by descent from a common ancestor.

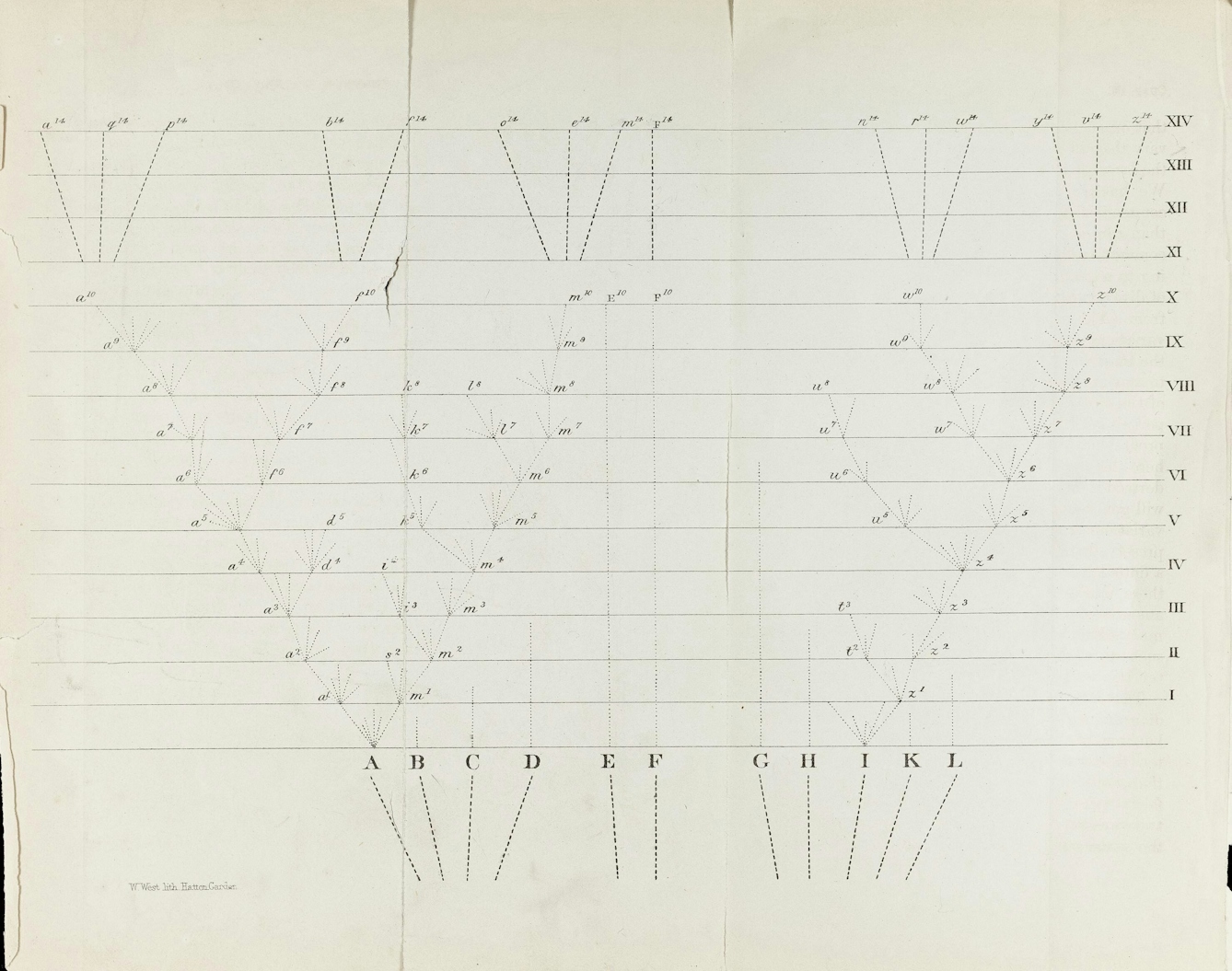

By the time – over 20 years later – that Darwin published ‘On the Origin of Species’, his small notebook sketch had grown into this illustration (the only one in ‘Origin’). In the matching text, Darwin describes a metaphorical ‘tree of life’ – concluding: “As buds give rise by growth to fresh buds, and these, if vigorous, branch out and overtop on all sides many a feebler branch, so by generation I believe it has been with the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its ever branching and beautiful ramifications.” Darwin’s image has greatly Influenced the illustrative use of phylogenetic trees, still used by biologists in the 21st century.

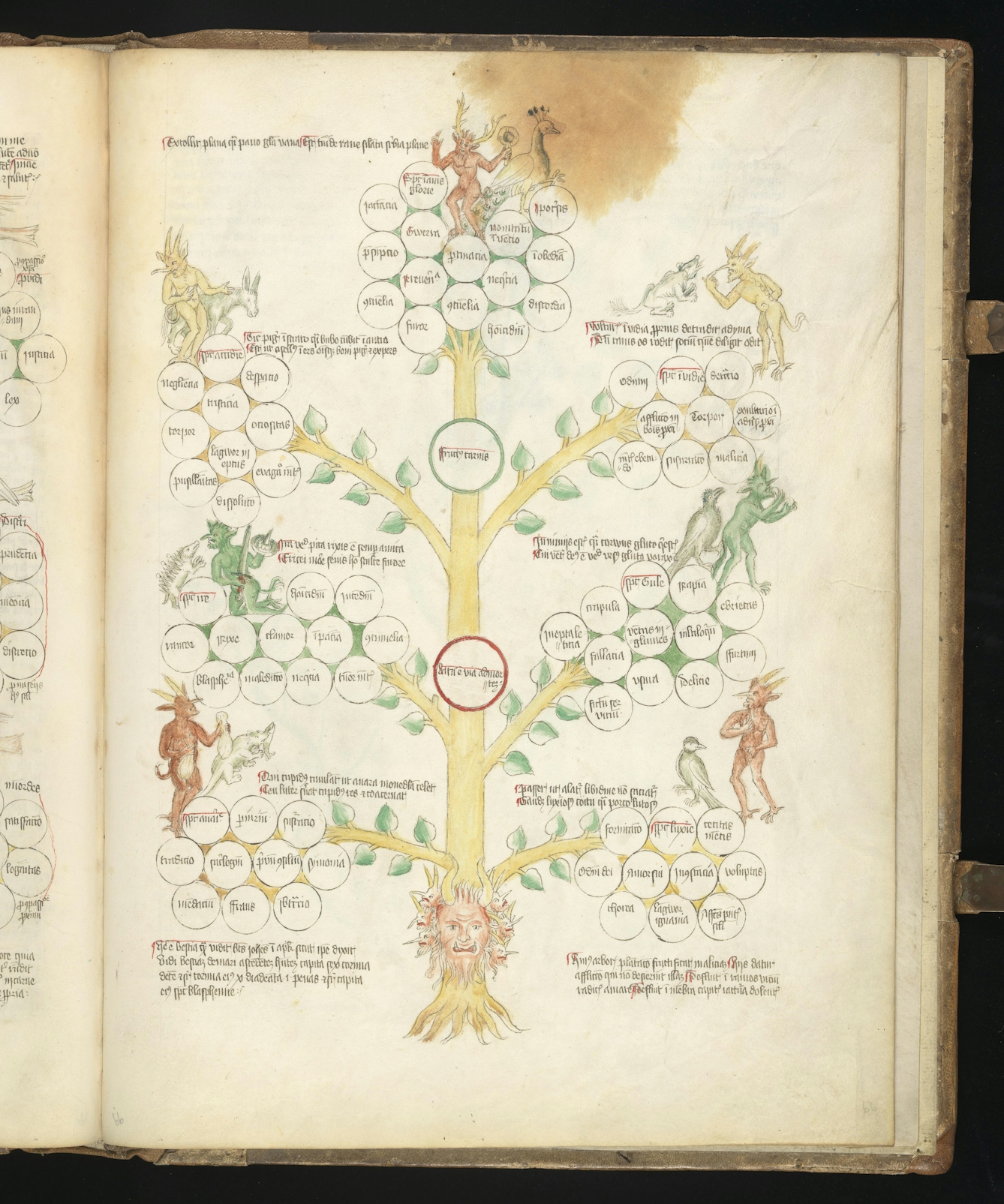

Creating a visual metaphor from a tree was by no means an invention of Darwin’s. As historian of science Petter Hellström has argued, it is an idea that has deep roots and has been used in different cultures for centuries. This 15th-century manuscript features a ‘Tree of Seven Vices’ (pride, sloth, anger, avarice, envy, gluttony and lechery are all visually represented), referencing the apple falling from the tree of knowledge in the Garden of Eden in Christian belief.

A longer-lasting visual metaphor of a tree stems from the tree of Jesse: a depiction in art of Jesus Christ’s ancestors in the form of a tree rising from the ground from Jesse of Bethlehem, the father of King David, and branching out through Jesse, through his descendants, to Jesus. This is the origin of the term ‘family tree’ to visually represent genealogical relationships.

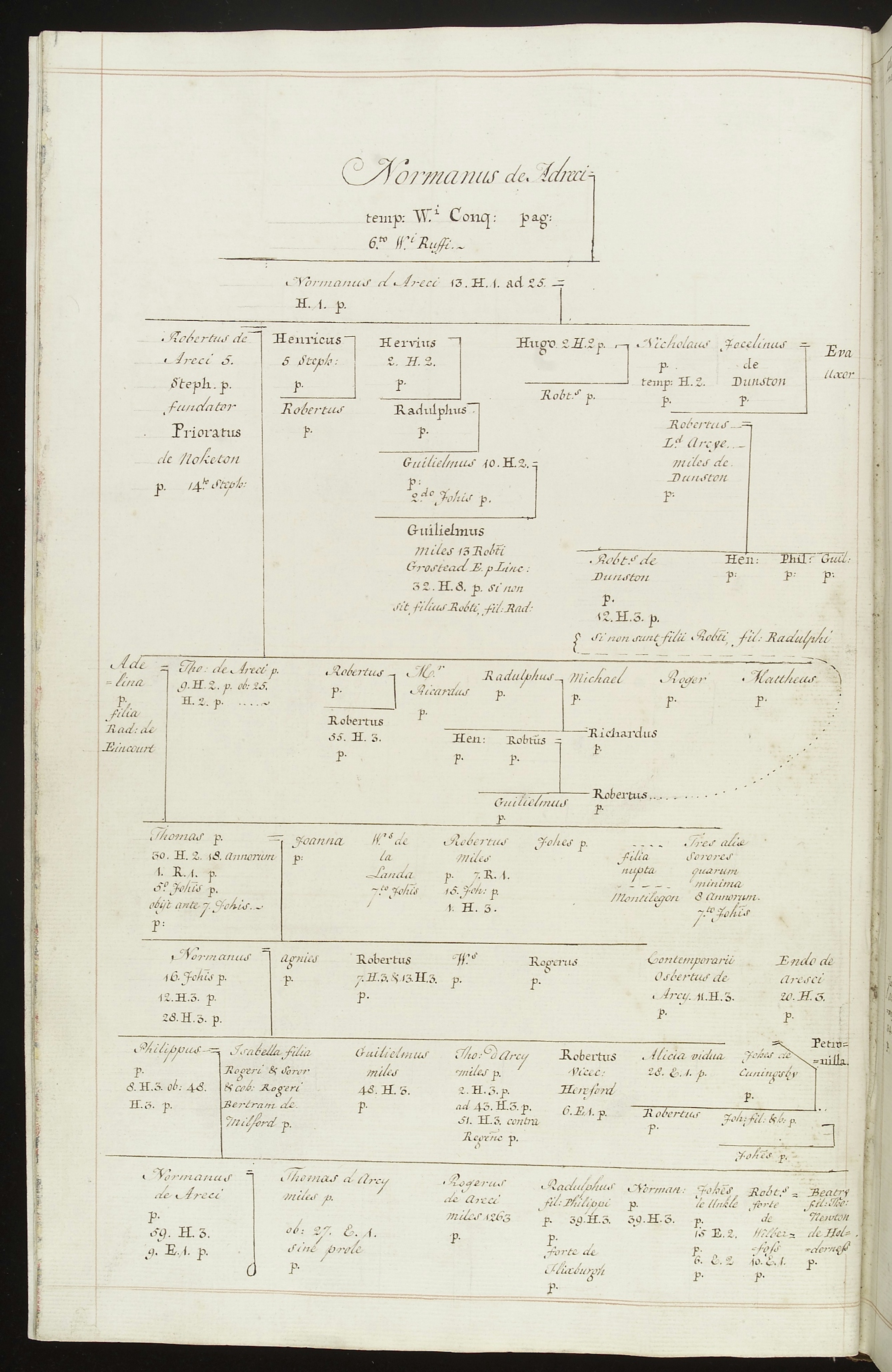

Family trees have been used for centuries. During the medieval period, they were commonly known as ‘pedigrees’. This English example from the 18th century shows the relationships between the “Right Honourable Families of the Lords D'Arcie, Conyers and Mennil, and of the Right Worshipfull Family of the Meltons of Aston”. Pedigrees were particularly important to prove claims to land, estates and titles.

This image is a representation of the ‘Great Chain of Being’, which developed in medieval Christian Europe from Classical origins. It held that that the structure of all matter and life was arranged in a hierarchical chain by God, that descended from Him down through angels, humans, animals, plants and finally to minerals. This hierarchical arrangement would feed into later visual trees of life.

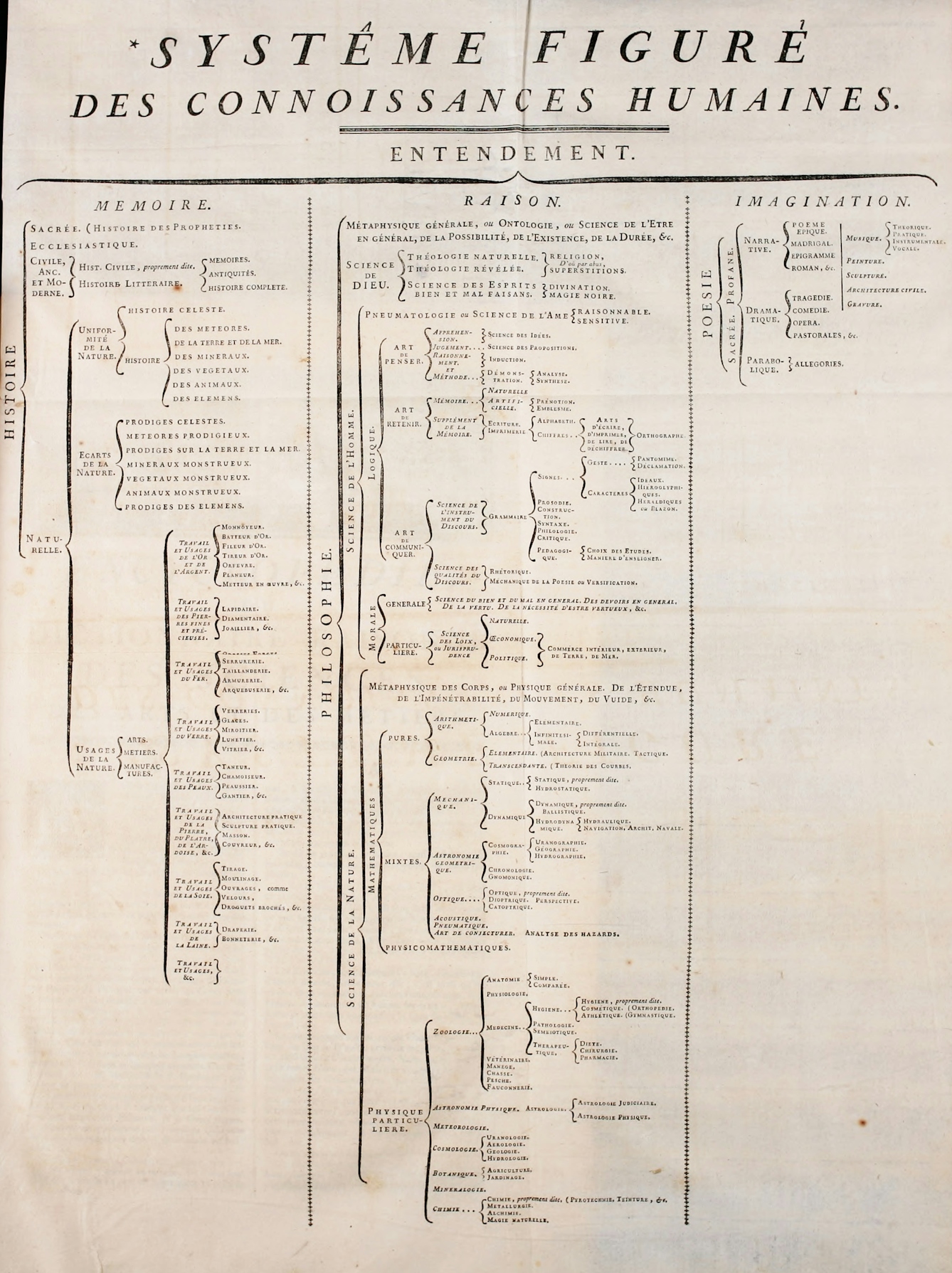

Such visual orderings of life had their equivalents in the seemingly more rational age of the Enlightenment. If God had previously structured life in a particular order, could the structure of human knowledge now also be arranged? The so-called ‘Tree of Diderot and d’Alembert’ – from their apogee of Enlightenment thought, the Encyclopédie – was an attempt to do just that. ‘Memory’/History, ‘Reason’/Philosophy, and ‘Imagination’/Poetry form the three main branches. We have moved from a medieval metaphor to a rational taxonomy and God – in the form of Theology and Religion – has been relegated to a lower branch, under Philosophy.

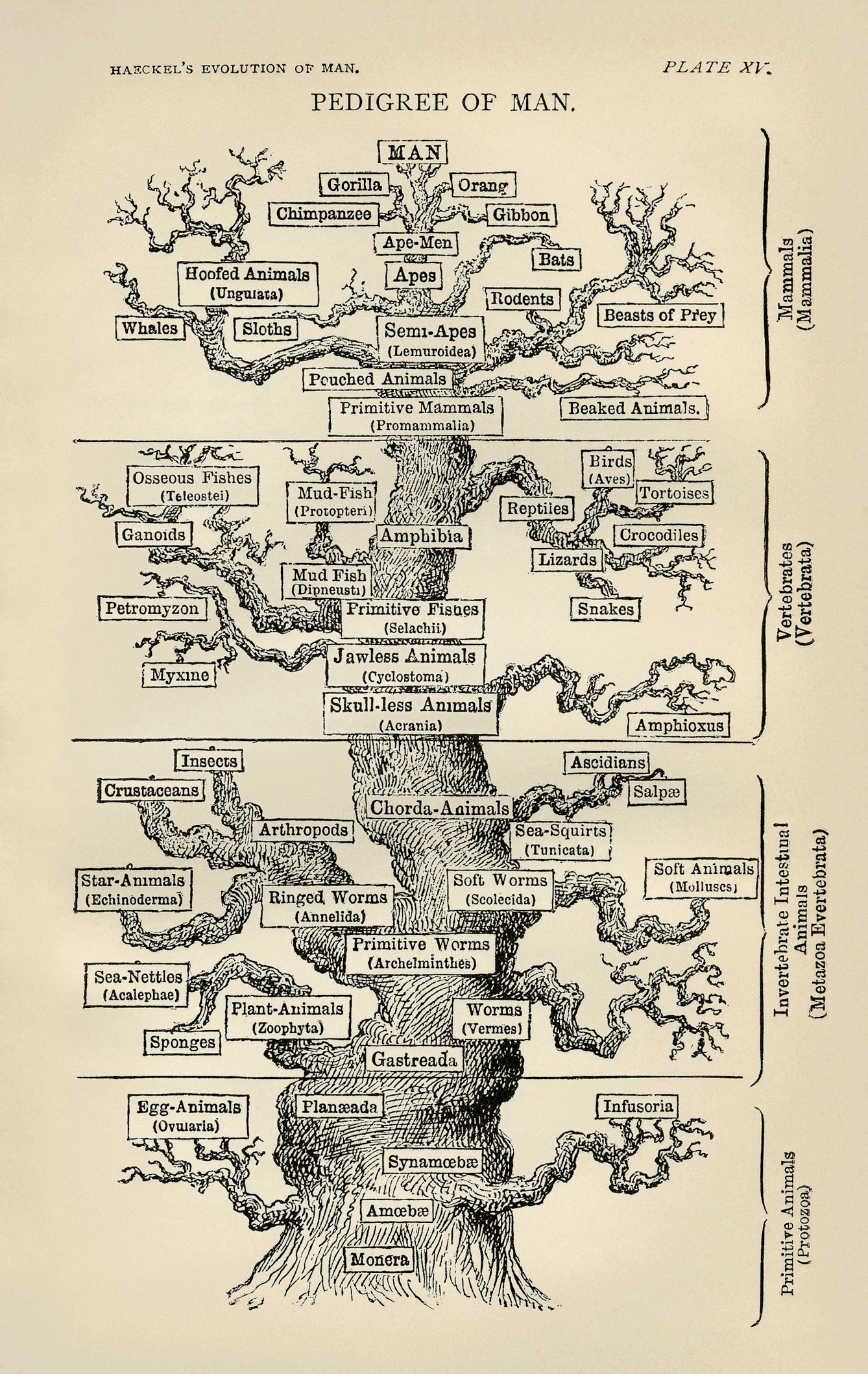

The German biologist Ernest Haeckel constructed trees of life to represent his thinking. Here you can see how he draws on ideas of both family trees and the Great Chain of Being to create his Pedigree of Man, here in the English translation of ‘The Evolution of Man’, published in 1879. Unlike Darwin’s illustration, this is a more linear tree, which shows development from ‘lower’ to ‘higher’ species.

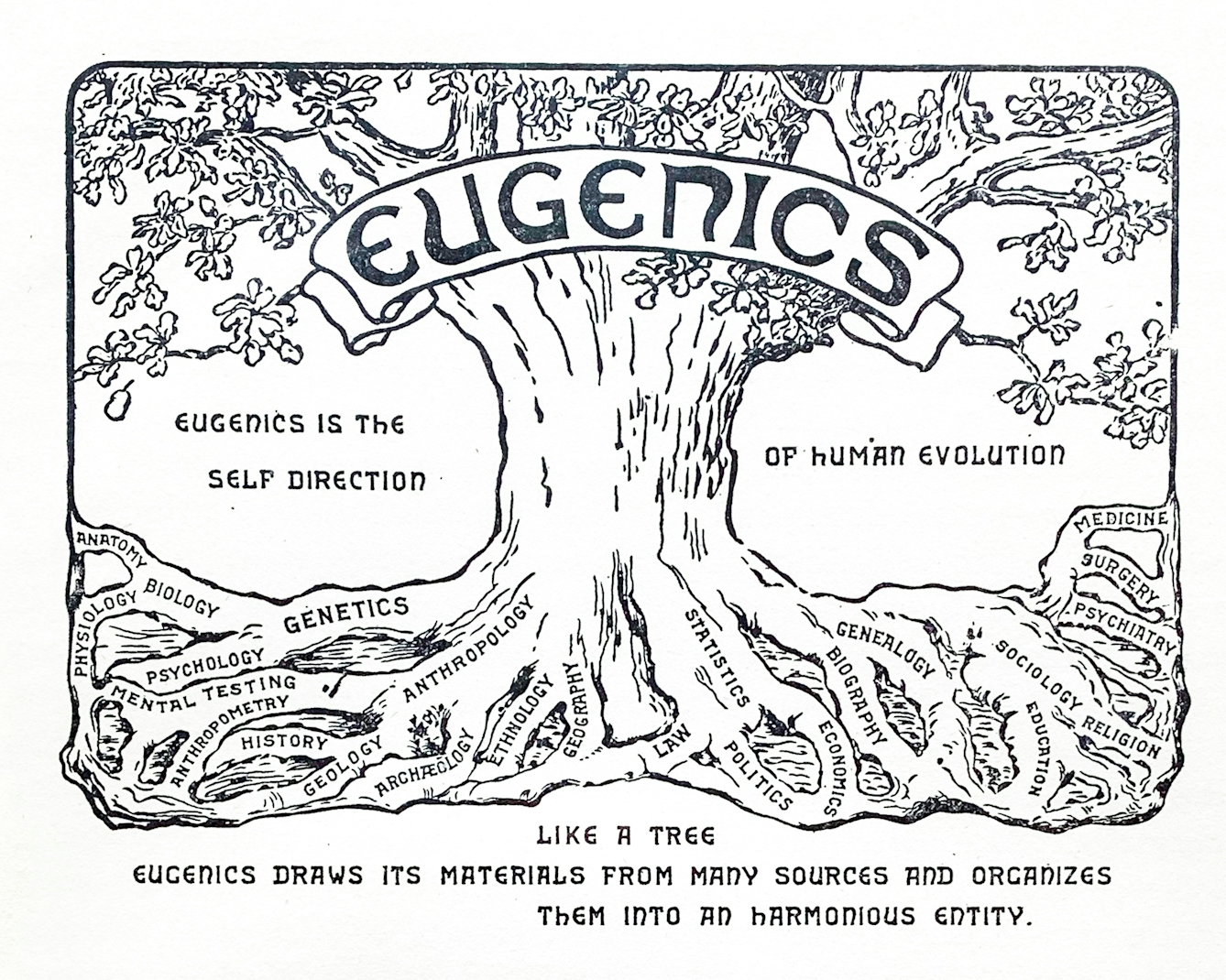

The use of the image of a tree – particularly this specific image – was something utilised by the promoters of eugenics. No doubt the healthy, natural connotations of a blooming tree fitted with the worldview of people who were promoting selective breeding. As leading historian of eugenics, Joe Cain has also written, “The metaphor of a tree with many roots and branches was intended to identify eugenics as a subject with multidisciplinary sources and to encourage participation from many types of experts.”

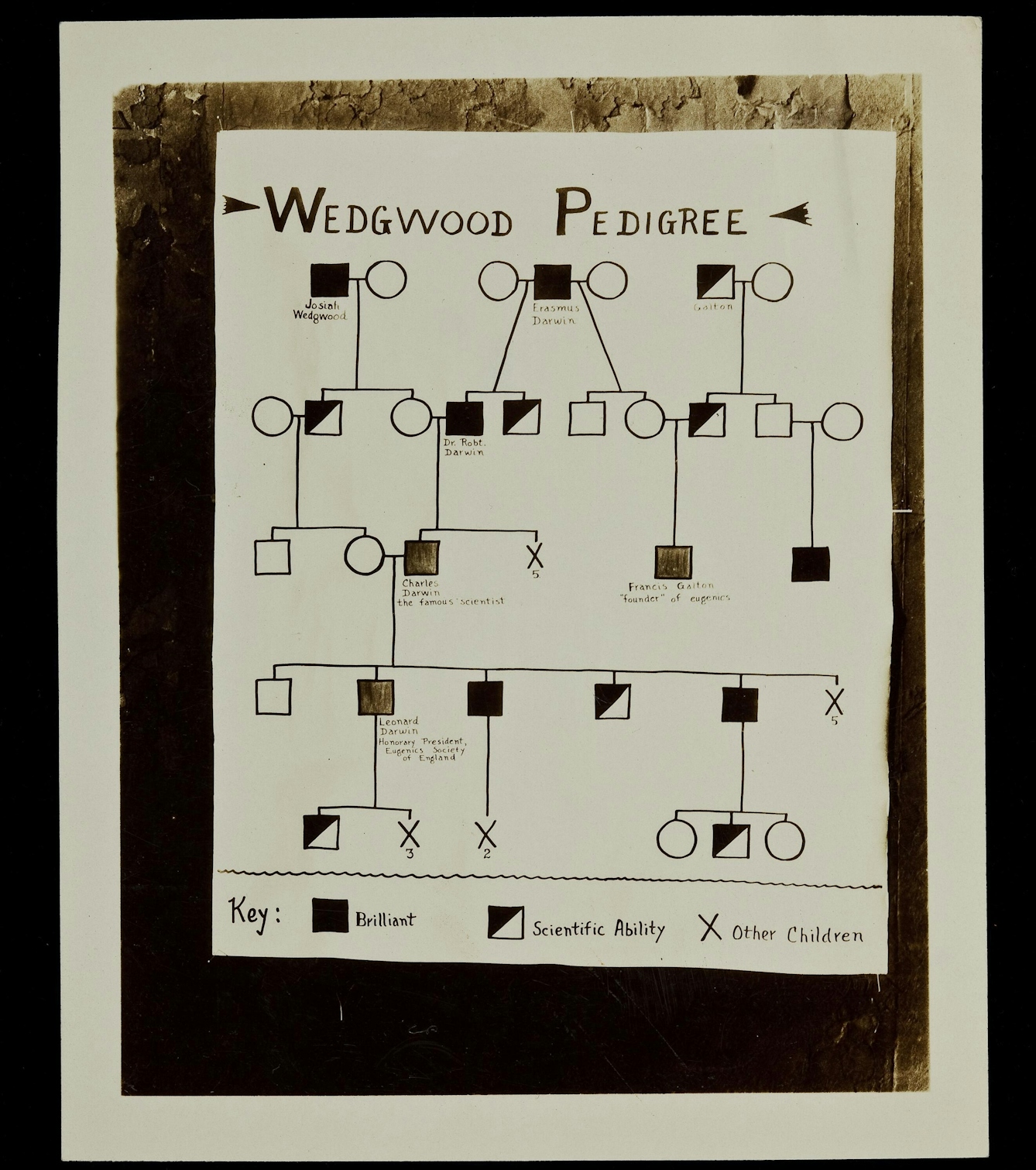

To eugenicists, ‘pedigree’ also meant the qualities of a person as well as family trees. The two meanings come together in the British Eugenics Society’s frequent use of family trees to promote what they saw (wrongly) as families “of good stock” marrying into each other to produce geniuses. This genealogical chart shows the pedigree that brings together the families that produce Charles Darwin and his half-cousin – and creator of the term ‘eugenics’ – Francis Galton.

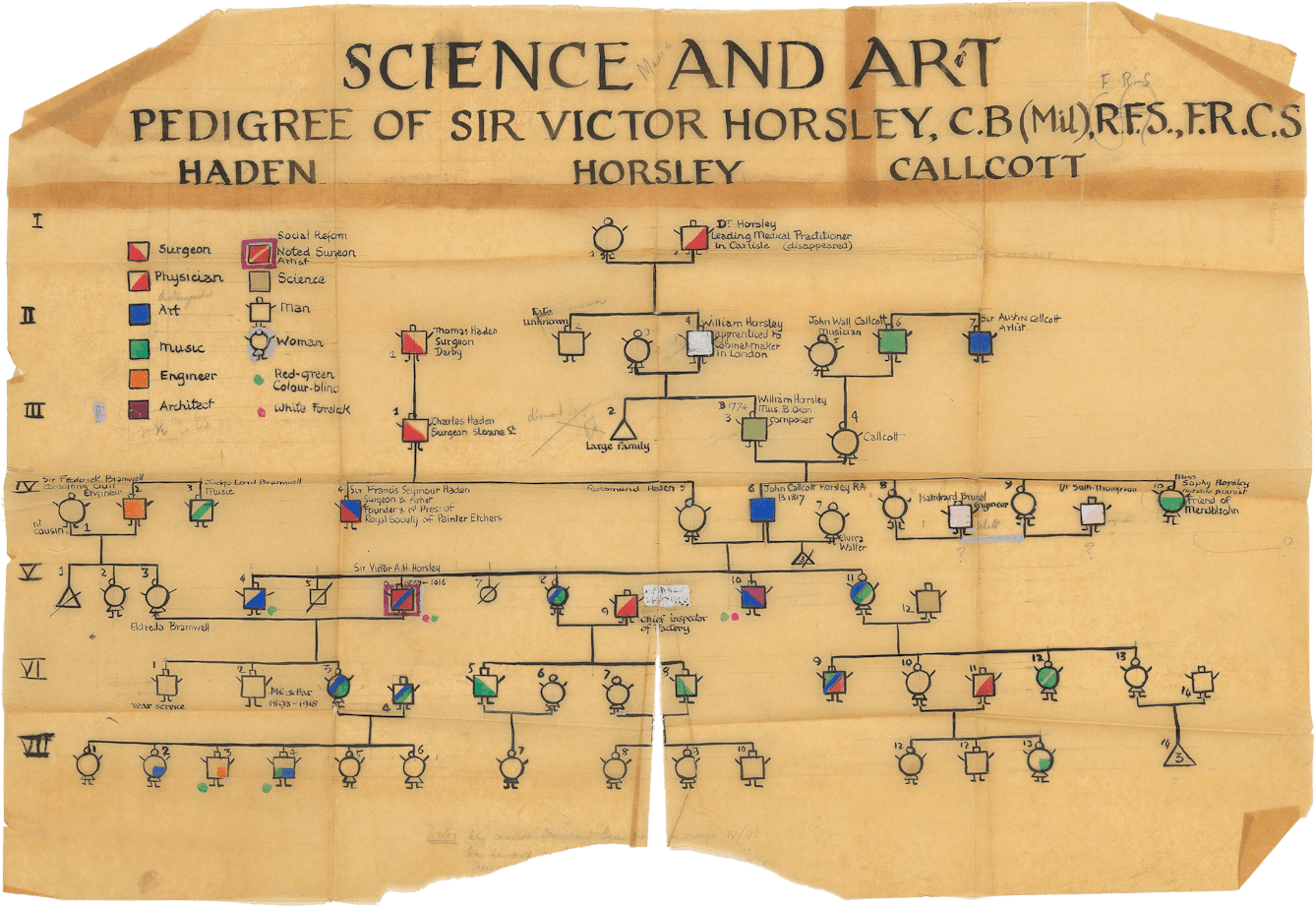

‘Pedigrees’ were used by the Eugenics Society to promote and propagandise their views. As shown here, they believed scientific and artistic ability (as well as moral qualities) were inherited, just like the colour of hair or of eyes. Genetic research later showed that many of the traits and diseases that the society believed to be hereditary are multifactorial in their causation.

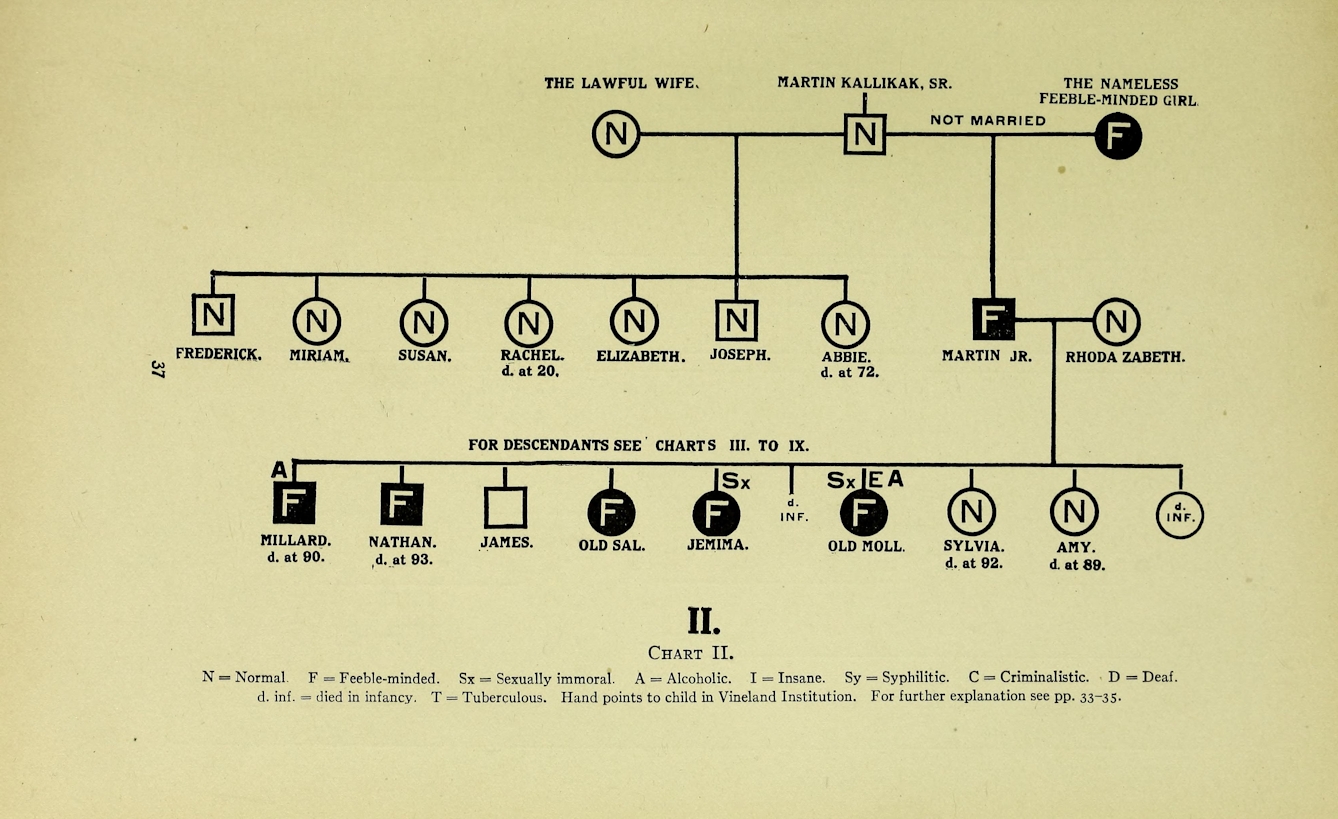

This pedigree is taken from one of the most infamous eugenics books – ‘The Kallikak Family’, published in 1912 by the American psychologist Henry H Goddard. This chart was used by Goddard as evidence to trace the inheritance of what were seen as “undesirable traits”. Later it was proved wrong – and shown that Goddard invented the family tree.

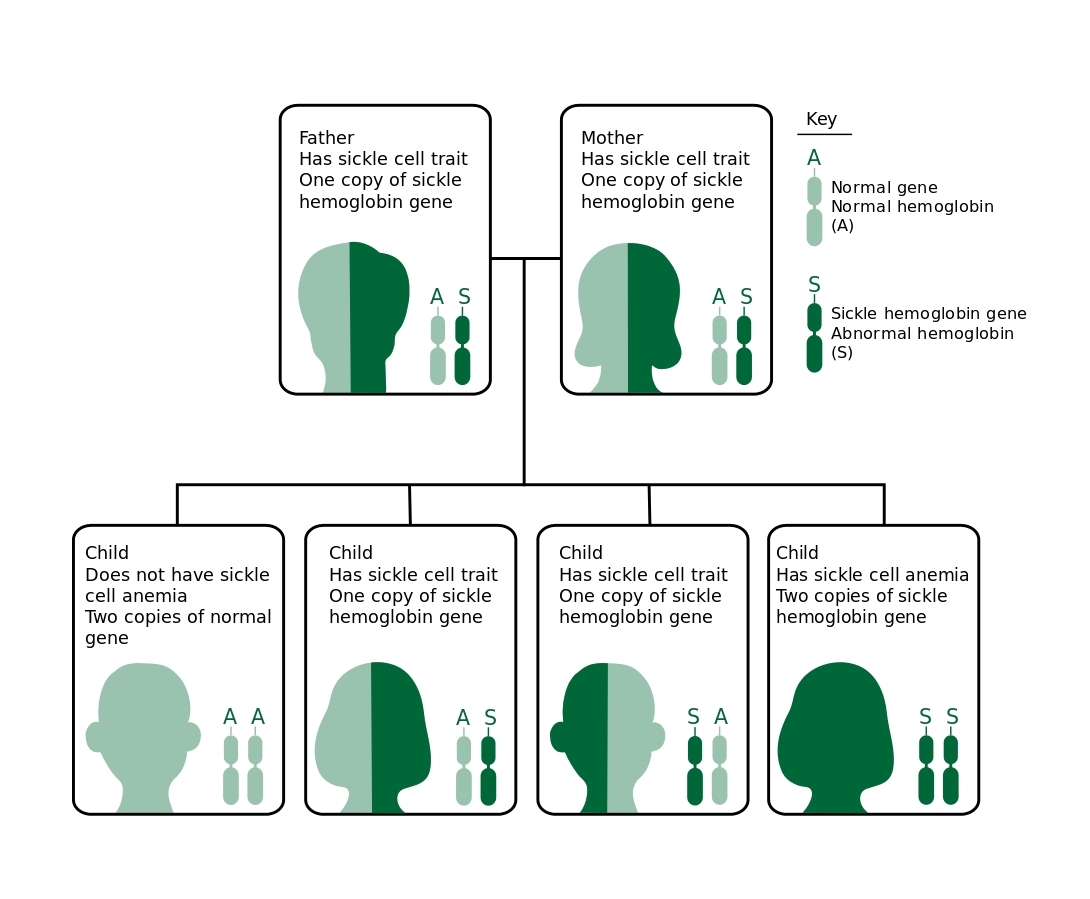

Such visualisations still have a part to play in science communication. However, examples such as this one – on the inheritance of sickle-cell disease – differs from the eugenic visualisations by showing the inheritance of traits that there is clear genetic evidence for, rather than those that eugenicists just presumed must be heritable.

These vertical models of trees can be contrasted with a horizontal model. For the French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, their notion of the rhizome – with no seed or origin point – challenges notions of ordered knowledge growing from a clear origin point. As such, the rhizome seems a handy metaphor for our seemingly uncontrollable and interlinked world.

About the author

Ross MacFarlane

Ross MacFarlane is a research development specialist at Wellcome Collection. He has researched, written and lectured on the collections and other topics at the intersection of death, folklore and medicine.