The impacts of noxious air are not only unequally distributed; in some cases, they are leveraged to cause deliberate harm. Forensic Architecture’s Imani Jacqueline Brown has been investigating the health impacts of tear gas used in the US against Black Lives Matter protesters. Imani tracks these chemicals back to the factories in which they’re created, and in doing so, uncovers a toxic legacy where pollution, violence and racism are intimately entwined.

On 25 May 2020, Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on George Floyd’s neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds, suffocating him. A few days later, cries of “we can’t breathe” reverberated across all 50 US states and six continents as activists braved the Covid-19 respiratory pandemic to denounce the devaluation of Black life.

Black US Americans realised that lockdown wouldn’t shield us from the pervasive “climate of antiblackness”. In the year following George Floyd’s murder, 229 more Black US Americans were killed by police, making police violence a prevailing condition of existence in an era some, including academics Jason W Moore and Françoise Vergès, have termed the “Racial Capitalocene”.

The Racial Capitalocene works as a corrective to the Anthropocene. The latter term suggests an evenly distributed responsibility for the disruption of the earth’s climatic systems, despite the massively uneven distribution of wealth, power and development along lines of geography and race. Before the Industrial Revolution, we should consider the genocide of Indigenous peoples, the dehumanising racialisation of Black bodies, and the commodification of ecologies as the points of departure for this new geologic era.

By reconceptualising structural racism as climatic and epochal, we can perceive the forces that initiated and maintain it, map their movement across time and space, and perhaps envisage the possibility of their end. Just as geologists speak of pervasive radiation as a signal, or sign, of the Anthropocene, we might speak of the extrajudicial killings of Black individuals as a signal of the Racial Capitalocene. During the racial-justice protests that followed George Floyd’s murder, another signal became apparent: tear gas.

Atmospheric solidarity

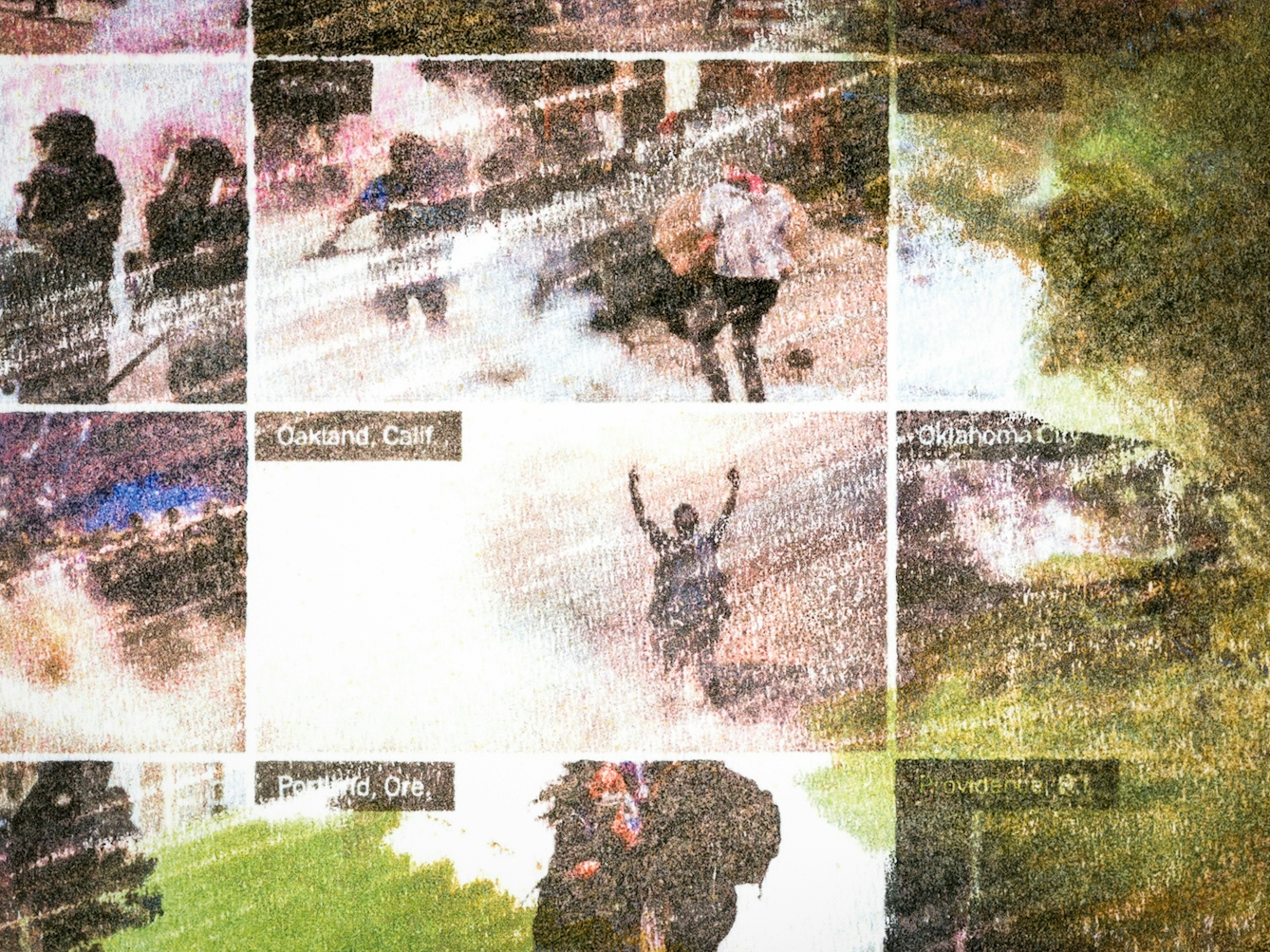

In the days after George Floyd’s death, over 700 municipal governments in the US classified appeals to the sanctity of Black life as ‘riots’, declaring states of emergency and imposing curfews. At least 100 police departments dusted off stockpiles of so-called “less lethal riot-control” munitions – gases, sprays, smokes and pyrotechnics. Many canisters had been sitting around so long that their contents had expired; chemical formulas protected as trade secrets may have degraded to form strange new compounds.

The tear-gas zeitgeist was deeply sensed in Portland, Oregon. For over 100 days, dense clouds of gas occluded video transmissions from Portland, transforming chanting crowds into a nebulous soup of retching silhouettes. Toxic plumes entered homes, businesses and an elementary-school yard.

Dense clouds of gas occluded video transmissions from Portland, transforming chanting crowds into a nebulous soup of retching silhouettes.

“During the racial-justice protests that followed George Floyd’s murder, another signal became apparent: tear gas.”

While “tear gas” is used as a catch-all for weaponised aerosols, the Chemical Weapons Research Center recovered the remains of nearly 50 types of munitions deployed by the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) and federal law enforcement.

Chemicals released include CN – 2-chloroacetophenone, commonly known as mace; OC – oleoresin capsicum, or pepper spray; PAVA, an irritant similar to OC, delivered in frangible projectiles called ‘pepperballs’; CS – a compound containing 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile, which irritates the eyes, nose, mouth and throat; and a noxious rainbow of coloured tactical smokes, containing heavy metals such as lead and barium.

In mid-July, while Portland was occupied by militarised police from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), a green-grey fog began to seep through protective goggles and N95 masks. Activists reported severe new side effects, including vomiting, dizziness, menstrual disorders and feelings of suffocation.

They also began to notice a new addition to the by then familiar litter of spent munitions: grenades labelled “Military-Style Maximum Smoke HC”. Hexachloroethane (HC), the active ingredient in HC smoke grenades, is a suspected human carcinogen that inhibits functions of the central nervous system. HC was phased out of use by the US military because of its impact on soldiers’ health, but used liberally by DHS against racial-justice protesters.

As a researcher with Forensic Architecture (FA), a human rights agency based at Goldsmiths, University of London, I am actively investigating these events. Working in partnership with Imperial College, we have been creating 3D models to simulate the dispersal of toxic chemicals, evidencing their impact on populations and environments. We’ve applied the methodology to past case studies in Gaza and Chile, and will adapt it to Portland in support of state-level efforts to ban tear gas.

Still, structural racism will not be dismantled through piecemeal bans. PPB’s current “use of force” policies ban the use of fire hoses and canines against crowds, suggesting that the optics around these methods are too closely associated with the racist violence of the 1950s and ’60s Civil Rights Era. If the deployment of tear gas – itself a violation of extant policy – is heir to dogs and hoses, what new forms of repression might come next?

Today’s extreme “crowd control” measures themselves succeed policies that barred Black people from setting foot in Oregon for more than 80 years. To end police violence once and for all, we need to deconstruct and dismantle its structural foundations. To understand those foundations, we need to track HC’s chemical trail backwards across time and space, from point of deployment in Oregon to point of production in the Deep South.

“Like racism, toxic chemical agents like HC cannot be contained. They seep beyond racialized communities, infiltrate the world at large, and settle within human reproductive organs.”

Inertia seeps

In search of HC’s origins, I looked to Louisiana, a state where police “use of force” policies were historically defended as a means to control the enslaved population. Back in October 2020, I had initiated another FA investigation into environmental racism in Louisiana’s Petrochemical Corridor. There, 200 of the nation’s most polluting industrial facilities occupy the grounds of formerly slave-powered plantations, where lethal conditions historically produced a negative demographic birth rate among the enslaved population.

Many descendants neighbour those facilities, which are permitted by Louisiana’s Department of Environmental Quality to release over 200 pollutants, including hexachloroethane. Consequently, they breathe some of the most toxic air and bear some of the highest cancer risks in the US.

The hexachloroethane haunting Black-descendant communities in Louisiana is not destined to fill smoke grenades, but is instead an ingredient in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics. Occidental Petroleum Corporation’s facility in Geismar is a major producer of PVCs and the region’s greatest emitter of HC. The state permits HC leaking, spilling and seeping from furnaces, cooling towers, waste-water systems, incinerators and storage tanks, contaminating soil, groundwater, air and flesh.

I found one producer of HC smoke grenades further upriver in the state of Arkansas: Pine Bluff Arsenal, the US Army’s primary manufacturer, research facility and training base for pyrotechnic munitions, including HC. Like the industrial plants in Louisiana, the arsenal is located within a riverine delta on top of fallow slave plantations. It borders a majority Black-descendant community whose ancestors were enslaved on its grounds. Within one mile of the facility are several schools, churches and a recreational water park.

In the Racial Capitalocene, structural violence seeps with inertial force from deep ruptures opened by colonial conquest; it accumulates, generation after generation, as geologic and atmospheric strata.

Hexachloroethane horizons

Under the Chemical Weapons Convention, hexachloroethane is classified as a chemical weapon and banned from use in international warfare. Deployed in conflicts between racial-justice activists and the state, it is rebranded as a “riot-control agent” and sanctioned by law. When it contaminates Black neighbourhoods in Louisiana and Arkansas, it is a permitted emission. Legality shifts in accordance with the perceived value of the targets. Signals of the Racial Capitalocene will continue to emerge and mutate until Black communities, and Black lives, are considered inherently valuable.

Yet, like racism, toxic chemical agents like HC cannot be contained. They seep beyond racialised communities, infiltrate the world at large, and settle within human reproductive organs. Chemical contamination is prefigured by our unredeemed colonial past. Must it be our common future? Facing a hexachloroethane horizon, perhaps the world can finally understand the meaning of the phrase “no life can matter until Black lives matter”.

This article was edited by Katie Urquhart and Jackson Howarth from It’s Freezing in LA! and is part of a series of articles about toxicity. It also appears in Issue #9 of It’s Freezing in LA! magazine.

About the contributors

Imani Jacqueline Brown

Imani Jacqueline Brown is an artist, activist and researcher from New Orleans. She is currently a researcher with Forensic Architecture, based at Goldsmiths, University of London, and a Visiting Lecturer at the Royal College of Art.

Fungai Marima

Fungai Marima is a multimedia artist who was born in Zimbabwe and is currently based in London. Her work investigates themes of displacement, memory, trauma and the female body, highlighting her Zimbabwean heritage and personal experiences. Fungai has a BA in Fine Art from Havering College and an MA in Printmaking from Camberwell College of Art. She was selected to be part of the prestigious London Grads Now 2020 exhibition at Saatchi Gallery, London. Her work has also been exhibited at Kings Place, Copeland Gallery and Coningsby Gallery.