From hydroelectric dams to pylons, the 20th-century architecture of electricity inspired a new kind of awe.

Titans in the landscape

Words by Ruth Gardeaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Serial

The architecture of electricity had as awe-inspiring an appearance as the machinery it housed. Such structures were often described as ‘temples’ or ‘cathedrals’, using quasi-religious language rather than engineering terminology.

Printed in a Canadian newspaper to celebrate the laying of the transatlantic cable in 1858, E J O’Reilly’s poem prophesied the conquest of the world by electrical technology. ‘The Atlantic Cable’ eulogised the unstoppable march of progress promised by electricity, and the international prosperity and friendship it would bring in its wake. Human mastery of nature was integral to this vision of modernity.

The possibility of wireless communication over distance, another testimony of electricity’s invisibility and impalpability, only increased the public’s sense of wonder.

Away from the unseen cable running across the bed of the Atlantic Ocean, visible manifestations of the electricity network began to spread through the urban and rural landscape. These colossal markers of the steady spread of electrical power – power stations, transmission towers, dams, electric rails – were formidable signifiers of human control over the natural environment.

For many, electrical plants and powerhouses were not seen as carbuncles on the face of nature but, like the telegraphic cable, monuments to modernity. Some became must-see sites on American tourist trails. Henry Ford’s powerhouse at his Highland Park factory had large windows designed to provide magnificent views into the machine rooms. The English writer Arnold Bennett was awestruck after a visit to a New York power station:

“Immaculately clean… shimmering with brilliant light under its lofty and beautiful ceiling, shaking and roaring with the terrific thunder of its own vitality, this hall in which no common voice could make itself heard produced nevertheless an effect of magical stillness, silence, and solitude… It was a hall enchanted and inexplicable.”

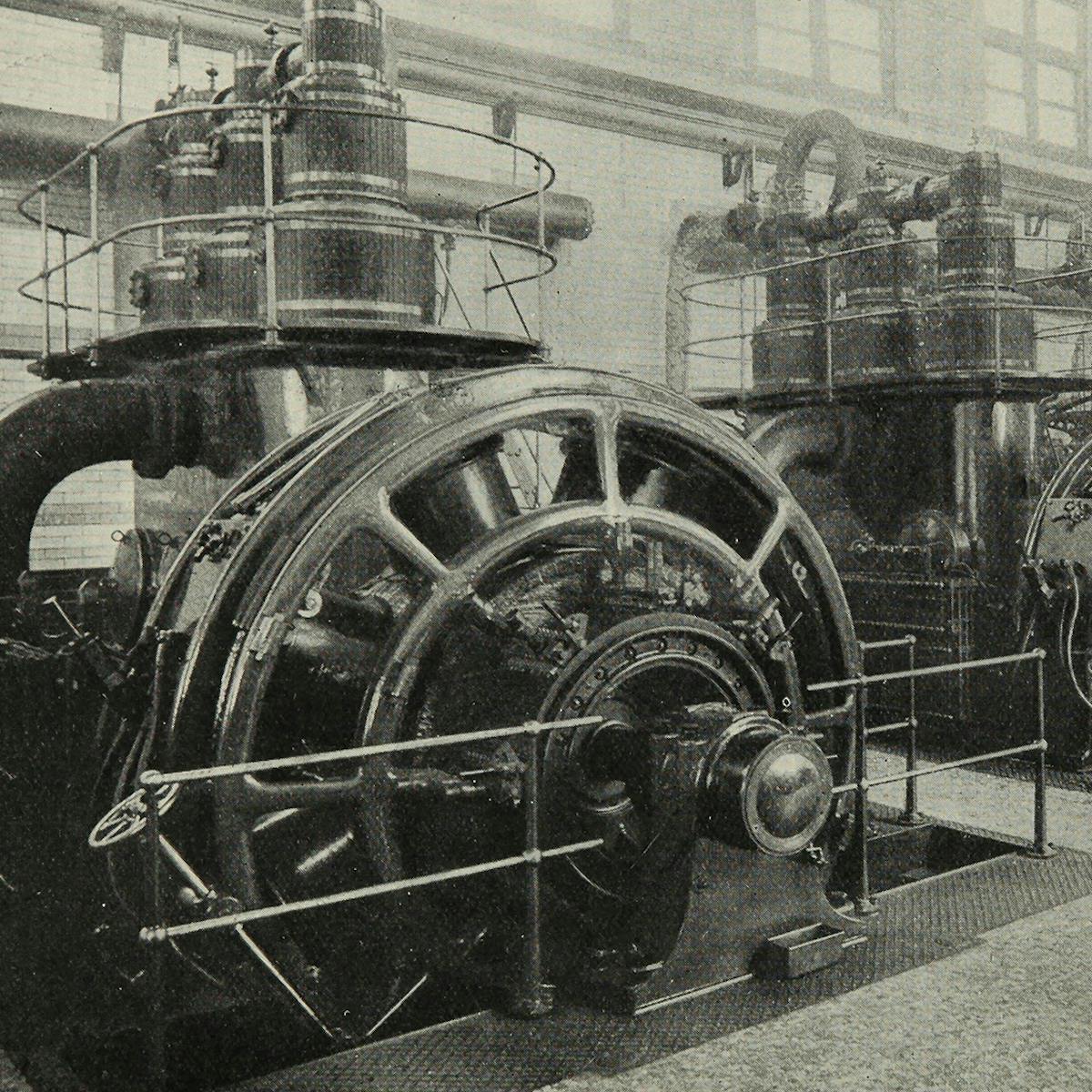

Hydro-electric power stations such as the one that opened at Niagara Falls in the 1890s also became popular tourist destinations. H G Wells was one of many visitors who were more interested in the electrical machinery than in the falls themselves. He wrote that the Niagara Falls dynamos represented the “human will made visible, thought translated into easy and commanding things.” They were “clean, noiseless, and starkly powerful… noble masses of machinery, huge black slumbering monsters, great sleeping tops that engender irresistible forces in their sleep”.

In pictures

The hydroelectric power station exemplified the idea of humankind’s control over nature through technological advancement.

Attitudes to the sight of pylons have shifted in the decades since their early appearance in the landscape in 1910s America.

For Henry Adams, the gigantic electrical machinery was both seductive in its grandeur but also spiritually alarming.

Electrical machinery such as dynamos, a popular attraction among visitors, was seen as a symbol of scientific progress and civilisation.

“Hewn out of solid rock”, Snoqualmie Falls Hydroelectric Power Station was a potent symbol of humankind’s dominion over nature.

The imprint of electrical power on the wider landscape was variously seen as a dynamic sign of progress and as an unsightly scar on nature.

Powerhouses became unlikely stops on the tourist trail, where visitors were awed by the immense size and scale of the machinery.

Electricity’s potential significance for transportation, leisure, technology and entertainment prompted as keen a public interest as light shows.

A similarly sublime expression of electricity’s power was offered by the American writer Frank Waters, who in 1946 declared the Hoover Dam to be “the Ninth Symphony of our day” and “The Great Pyramid of the American Desert”. It was enormously popular with tourists, and was visited by 750,000 people in 1934–35, as many as visited the Grand Canyon in the same year.

When long-line transmission systems began to criss-cross the American landscape, reaction was often enthusiastic. The Los Angeles Times wrote in 1913 about how “electric energy from the far-off Sierras stretched a hand robed with lightning across the gulf of valleys and mountains to the doors of the city”. In the 1920s the Chicago architect E H Bennett acknowledged that “to the mind of any imagination there is at times something irresistibly fine in the aspect of great airy structures stalking the hills”. Transmission towers also became, like the transatlantic cable, the unlikely objects of poetic veneration. In 1933 Stephen Spender wrote his paean to pylons, emblems of progress and modernity:

“But far above and far as sight endures

Like whips of anger

With lightning’s danger

There runs the quick perspective of the future.”

But as the century wore on, attitudes to the “iron forests” shifted and opposition became more vocal. The environmental movement gathered momentum in the 1960s, and the “march of the towers” was increasingly decried as a desecration of the landscape, much as wind turbines are today.

It was not only the aesthetics of the creeping electrical network that caused disquiet. The bewildering technological potential embodied in the machinery of electricity also prompted unease and anxiety, perhaps best expressed by the historian Henry Adams in his 1907 autobiography. He wrote of the dynamo’s “huge wheel, revolving within arm’s-length at some vertiginous speed”, whose silent power seemed to possess an occult and incomprehensible mystery. Adams feared that worshipping this symbol of the modern machine age had the potential to irrevocably displace other, more ‘spiritual’ values such as art, or faith. Hinting at his ambivalence he composed his ‘Prayer to the Dynamo’: “Mysterious Power! Gentle Friend! Despotic Master! Tireless Force!”

This illustration of a speeding electrically-powered train engine perfectly illustrates the association of electricity with speed, progress and modernity.

The fear that Adams expressed about the mysterious industrial apparatus of electricity was not unlike the superstitious anxieties that Thomas Edison had observed among his workforce some 30 years earlier. According to Edison, when his electrified cables were to be buried underground, “the Irish laborers of the day were afraid of the devils in the wires”. This perception of electricity’s supernatural power is probably what lay behind Edison’s epithet, the ‘Wizard of Menlo Park’.

It may seem ironic that the mysterious qualities of electricity – its invisibility and immateriality, its silent power and intangible force – prompted such fears and also inspired enchantment and wonder. Yet electricity is full of ambiguities: its death-dealing and life-giving force, its capacity to illuminate and to extinguish, to heal and to inflict pain, to reawaken and to annihilate.

Thunderous lightning, electric eels, galvanised corpses, floodlit facades and monumental machinery have inspired the most profound emotions in human beings. Through the words and images of those who have encountered its enigmatic and inscrutable power – whether poets, historians, engineers or scientists – we can begin to understand how electricity has shaped the human psyche.

About the author

Ruth Garde

Ruth Garde is a freelance curator and writer, focusing on the fields of history, art, architecture and heritage. Over the past fourteen years she has worked extensively with Wellcome Collection, writing and curating a variety of projects encompassing history, human health, art and science.